Exploiting BBs Who Never Donk-Bet

In a single-raised pot (SRP), a BB caller should almost always check when out of position (OOP) to the preflop raiser (PFR). This is especially true in MTTs, where the ante incentivizes an especially wide and weak BB calling range. However, there are specific flops where BB’s equilibrium strategy includes a fair bit of donk-betting.

How can you, as the preflop raiser, best exploit an opponent who misses these bets?

It’s more complicated than you might think, as the answer depends on:

- Why they miss these bets

- And what other deviations they may also make at future decision points

In the process, we will reach some larger conclusions about solvers, exploits, and nodelocking.

Understanding the Equilibrium

In order to understand the exploits, we must first understand why the equilibrium looks the way it does.

Donk-betting is a more important component of BB’s flop strategy when stacks are shallower and when the preflop raiser is working with wider ranges, so we’ll look at an example from a single-raised MTT pot with 20bb stacks. This is from a sim where preflop limps were not allowed, as the option of limping would distort the preflop ranges in ways that would make the solution less generalizable to other scenarios.

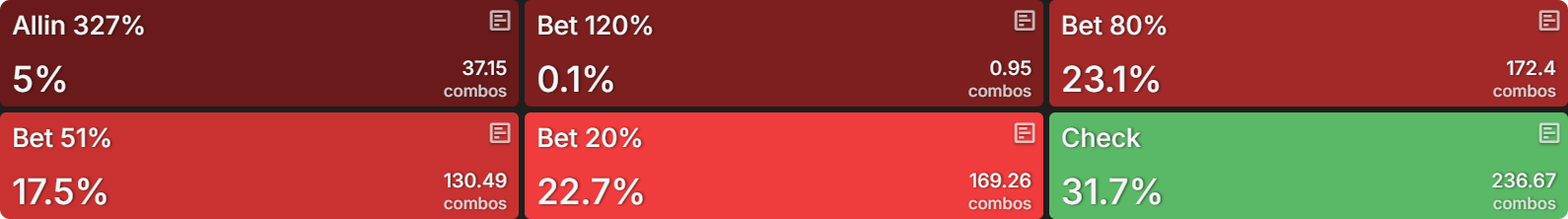

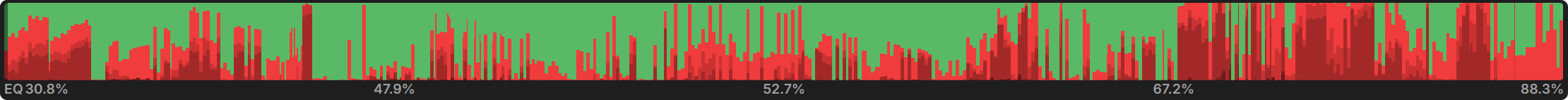

In this configuration, 764r is the flop on which BB has the highest equilibrium betting frequency, with nearly 70% of hands betting anywhere from 20% to 327% of the pot:

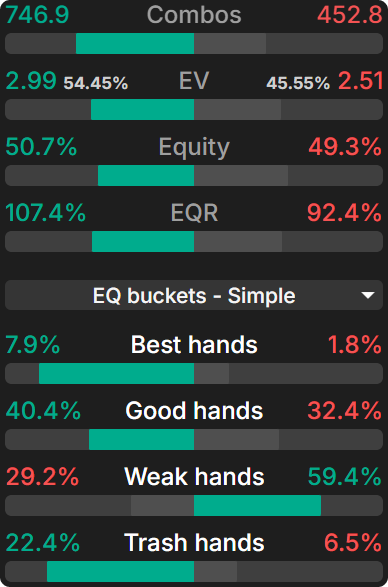

BB bets so often because this is one of the best possible flops for them, giving them a slight equity advantage and a substantial nuts advantage:

50.7% equity may not seem like much, but on the vast majority of flops, BB is at a substantial equity disadvantage in this configuration. On the worst flop (AK9r), they have just a measly 28% equity!

Despite this flop’s favorability for BB, BTN bets almost half their range when checked to:

Why do you think this is?

Formulate a Hypothesis

A great way to study with a solver is to identify a surprising result, consider it for yourself and, formulate a hypothesis that explains it, then design an experiment to test that hypothesis. So, let’s practice: how can it be the case that both players want to bet so often? Isn’t an expectation that BTN will not often c-bet the impetus for BB to develop a donk-betting range in the first place?

Your hypothesis doesn’t have to spring fully formed from your own mind. You can and should use tools to help you understand the range interactions underlying the phenomenon you’ve observed. Let’s take a look at the metrics after BB checks:

BB’s equity has dropped from 50.7% to 45%! They’ve also lost their nuts advantage. They still technically have more of the very best hands, but when “Best hands” and “Good hands” are taken together, BTN now enjoys a large advantage. What happened?

It seems like BB’s strong hands went disproportionately into their betting range.

That sounds reasonable enough, but not everything that sounds reasonable is correct. Let’s test this hypothesis.

What if BB Never Bets?

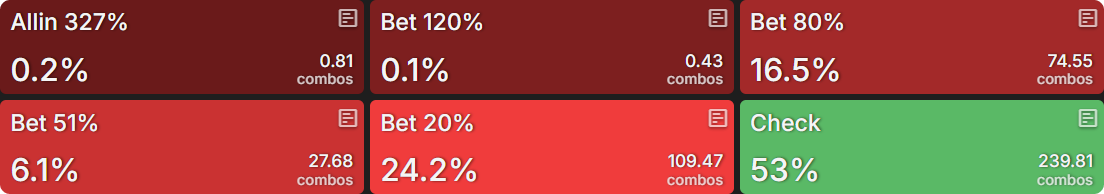

A simple nodelocking experiment should do the trick. According to our hypothesis, if we nodelock BB to check their entire range, BTN should lose most of their incentive to bet. Sure enough:

Essentially, on specific, highly favorable flops like this one (they are almost all low and connected), BB has many hands that want to force money into the pot early, before the board texture changes. This incentivizes them to bet those hands immediately, so when they check, the BTN can reasonably conclude they are less likely to have such hands, which incentivizes them to bet more aggressively. If BB does not donk-bet those hands, then BTN loses most of their incentive to bet (we’ll investigate later which hands still bet, and why).

So the Solver Was Wrong?

A common misunderstanding about solver strategies holds that they only “work” if your opponent also plays a solver strategy. But in fact, solvers’ equilibrium strategies are optimized so that there is nothing your opponent can do to yield a higher EV than play their own equilibrium strategy (that the solver calculated). If they deviate from that equilibrium by betting less often, that will sometimes work out well for them if you happen to have certain hands, but it will at least as often cost them EV when you hold a hand they would have preferred to bet into.

In this case, BB loses about 1% of the pot if they check their entire range even if BTN does nothing to exploit this deviation. The exploit shown above captures another 8% or so of the pot, so it’s well worth exploiting when you can predict a deviation. (I’m avoiding the word “mistake” here because this deviation is not much of a mistake unless you make it costly, and it could even be a good exploit itself against a population that bets too much when checked to.) But it’s important to understand that the GTO strategy retains its value even when your opponent plays exploitably in ways you can’t predict.

Which Hands Check?

The short answer to the question of how to exploit an opponent who does not donk-bet in spots where they should is to c-bet less often.

But that raises a new question: which hands should you still bet even when exploiting, and which should you shift into your expanded checking range?

There was an interesting detail in the nodelocked simulation that our hypothesis did not address: it is specifically the smaller, 20% and 50% pot bets that drop out of BTN’s c-betting strategy, leaving them with only the more polar, 80% pot betting range.

This provides a hint about which hands are checking and why. Usually, big bets come from a more polar range, while small bets tend to be some combination of thin value, protection, and semi-bluff. Comparing the Manhattan plots for the equilibrium vs the exploitative (IP) strategies reveals there’s something to that explanation but also suggests there’s more to the story.

In the equilibrium plot, we see small bets coming from all across BTN’s range, from strong hands to weak hands and everything in between. The exploitative plot does indeed show bets coming mostly from the top and bottom quarters of BTN’s range, but it’s not just the very best and very worst hands. In fact, BTN’s very best hands mostly check; it’s the next tier down which does most of the pure betting.

The strategy grid makes clear what’s going on here. The pure bets are all strong but vulnerable pairs, from A7 to TT.

These are not thin value-bets—they’re strong enough to get stacks in on the flop, if it comes to that—but they are all hands that benefit considerably from folds. By betting these hands, BTN often causes BB to fold one or even two live overcards.

The very top of BTN’s range, which consists of bigger overpairs, two pairs, and sets, is less vulnerable to free cards. These hands often bet 20% pot when that was in BTN’s arsenal, because such a small bet could induce floats and raises from worse, but they actively do not want the fold equity that comes along with a larger bet. While TT is happy to make QJ fold, KK would love QJ to see another card and perhaps turn top pair.

Regular blog readers may recognize this pattern recurs quite often, in many different early-street spots.

When a player has a low betting frequency, their most frequently bet hands are usually in this strong but vulnerable category.

Because these are the hands that most benefit from getting money into the pot immediately, before the board becomes less favorable.

As for which hands are not betting as part of the exploitative strategy, we have already discussed the less vulnerable strong hands. The other hands that shift into BTN’s checking range come from the middle and, to a lesser extent, the bottom of their range. Note, however, that even the bottom of their range has more than 30% equity. Such hands love getting folds, of course, but with that much equity, they don’t hate getting called either. This suggests the reason BTN prefers checking them if they know BB is checking their entire range: A stronger BB range can more easily check/raise and deny equity to these semi-bluffs.

Stacking Exploits

That gives us another hypothesis to test:

We can test it by further nodelocking BB to reduce their raising frequency.

Sure enough, if we halve BB’s raising frequency against the 20% pot c-bet, BTN bets more than ever and strictly prefers the smaller bet size (though that could change if we also nodelocked BB to reduce their raising frequency against other bet sizes)!

It looks like the default exploit against a BB who does not donk-bet the flops they’re supposed to is usually to continuation bet much less often, using a larger and more polar size when you do bet. However, if you think they will also not do a good job of check/raising, then you want to bet even more than you would at equilibrium, with an emphasis on small bets.

How realistic is it that an opponent would make both these deviations? That depends on why you suspect they aren’t donk-betting enough in the first place. I can think of three plausible explanations, each of which would entail its own exploit:

- The Unstudied – Donk-betting the flop is rarely correct for BB and is difficult to execute even when it is part of the equilibrium strategy. I often advise players just to check to the raiser 100% of the time unless they’ve explicitly studied when and how to donk-bet, and I don’t think it comes up often enough to be most people’s top study priority. So, it’s easy for me to imagine a pretty good player who nevertheless checks certain flops too often but who will respond to a c-bet with a good level of aggression. This is the sort of player against whom you want to check much more often.

- The Shark – A well-studied opponent might also choose not to donk-bet with the intention of exploiting you, if they think you will c-bet too often. Under that assumption, they should be looking to check-raise extra aggressively! The safest course of action for you would be to treat them like the unstudied player and decrease your c-betting frequency. The super-sharky high-level triple-counterexploit would be to c-bet aggressively to induce their aggressive check-raises and then respond extra aggressively to those raises. You better know what you’re doing if you choose that path.

- The All-Around Passive – Some players just aren’t comfortable driving the action. If their excessive flop checking is rooted in general passivity, they probably won’t often raise either, in which case the best exploit would be a high c-betting frequency. Note, however, that such a player might also have a stronger preflop range as a result of 3-betting less often, which could introduce yet another layer of exploit and perhaps some additional incentive to check.

Conclusion

Nodelocking and exploits can be tricky. Deviations are often correlated with one another, so as with any other solver work, you must understand the question you are asking the solver before you take its answer as the final authority.

Question #1

The first question we asked here, in essence, was:

Q: “How do I maximally exploit an opponent who fails to donk-bet the flop in cases where they should but plays well at future decision points?”

A: Reduce your c-betting frequency relative to the equilibrium, sizing larger and more polar when you do bet.

That’s a useful answer to have, and it’s important to note this strategy will increase your EV against an all-around passive opponent even if you do not make further adjustments.

Question #2

However, the second question we asked was:

Q: “How do I maximally exploit an opponent who fails both to donk-bet and to check/raise with sufficient aggression?”

This yielded a very different answer!

A: The best exploit against such an opponent is, in fact, to c-bet at an even higher frequency than you would have at equilibrium and for a smaller size (smaller sizes usually benefit most from an opponent’s passivity because they are supposed to get raised more often).

It may seem frustrating to get two contradictory answers as you add layers of complexity, so it’s important to recognize poker is not a game of perfection. You will never have perfect knowledge of an opponent’s strategy and so will never craft a perfect counterstrategy. As your understanding of the game grows, you will continue to make marginal improvements, refining and replacing adjustments you made earlier in your progress.

If you keep asking questions/seeking answers, you will keep growing as a player.

Author

Andrew Brokos

Andrew Brokos has been a professional poker player, coach, and author for over 15 years. He co-hosts the Thinking Poker Podcast and is the author of the Play Optimal Poker books, among others.

Wizards, you don’t want to miss out on ‘Daily Dose of GTO,’ it’s the most valuable freeroll of the year!

We Are Hiring

We are looking for remarkable individuals to join us in our quest to build the next-generation poker training ecosystem. If you are passionate, dedicated, and driven to excel, we want to hear from you. Join us in redefining how poker is being studied.