How Payout Structures Impact ICM

Last time we discussed the ICM considerations in game selection, we looked at field size, which has major implications regarding profitability, variance, and just how tight or loose one should play. Today, we will look at ICM considerations where the payout structure is concerned.

Whether a payout structure is standard, flat, or steep is relative, but for the purposes of this article, let’s make some assumptions.

- Typical MTT payout structures pay between 15% and 20% of the field, with the lion’s share of the prize pool being paid to the final table, with around 30-40% of the prize pool going to the final three players. This is what we would refer to as a standard payout structure.

- A flat payout structure rewards those who make the money more equally. Compared to a standard payout structure, less money will go to the eventual champion, with bigger prizes for the other finalists and also larger min-cashes. A flatter payout structure may also award more players with a prize.

- A steep payout structure does the opposite of that, with much more of the prize pool concentrated around the final money positions, especially the eventual winner. It may also pay fewer people overall.

At the extreme ends of both sides of the spectrum, the flattest payout structure possible is a satellite, where all players get a prize of equal value, while the most top-heavy payout structure is the winner-takes-all tournament. The strategic differences between these two types of tournaments are so significant it is like they are totally different games.

Bubble Factors

As we did in the field size article, the easiest way to grasp the strategic differences between flat and top-heavy payout structures is with the following Toy Game.

- We have a table with six players on it all with 20bb. This is a multi-table tournament, and the average stack on the other tables is also 20bb.

- We are in a 180-runner tournament that pays 27 players, and we are on the bubble with 28 players remaining.

We will simulate this tournament several times using different payout structures. We will then look at the Bubble Factors in each example to ascertain the strategic differences in each format.

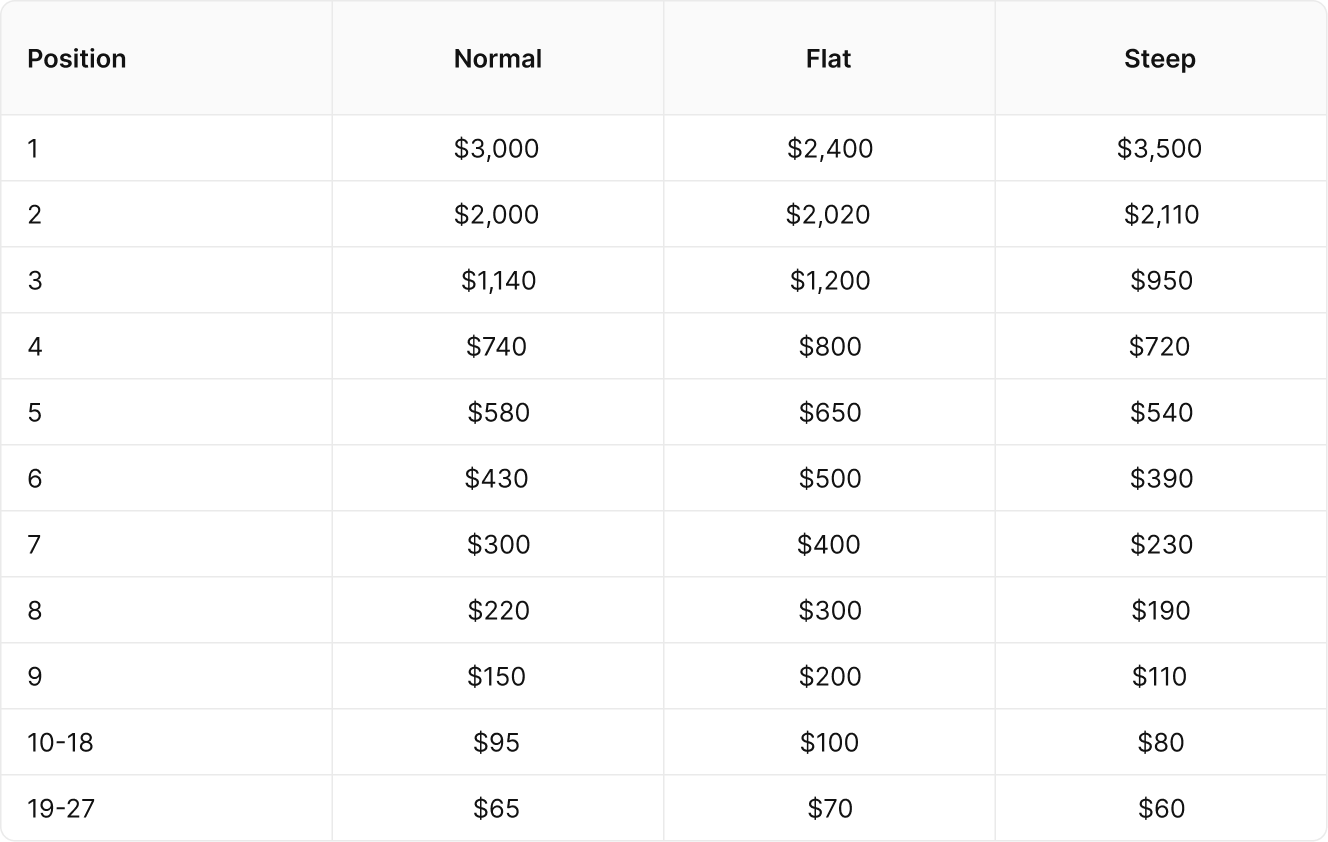

These are the three payout structures:

The ‘Normal’ payout structure has the same ratios as a PokerStars 180-man SNG; a very common payout structure. The flat payout structure pays less for first place but more for every other payout, including the min-cashes. The Steep payout structure pays everyone a little bit less except for the final two players.

We could have increased the number of min-cashes for the Flat and decreased them for the Steep, but in the interests of having the comparisons as close to each other as possible, we went with 27 players getting paid, with one pay jump before the final table.

Below are the Bubble Factors for everyone in the standard payout structure:

Everyone has the same Bubble Factor of 1.41, which, if you have read our article on Bubble Factor, you will know means that they would need 59% equity to get all-in against somebody else at this table.

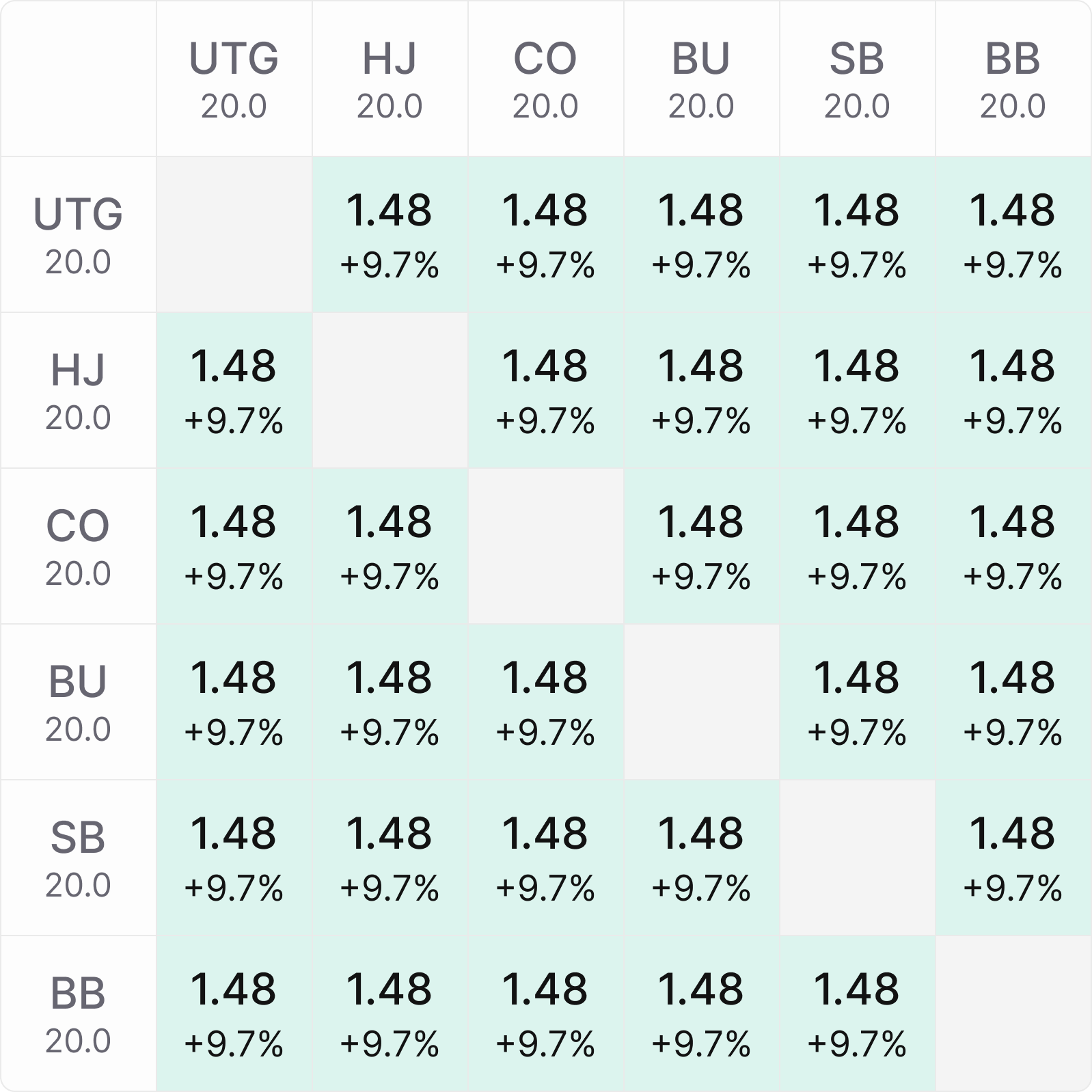

Let’s compare that to the Flat payout structure:

The Bubble Factor is higher – 1.48, meaning a player would need 60% equity to get all-in against each other. A small difference, but it is tighter. With less money up top, securing the min-cash and laddering is a little more important.

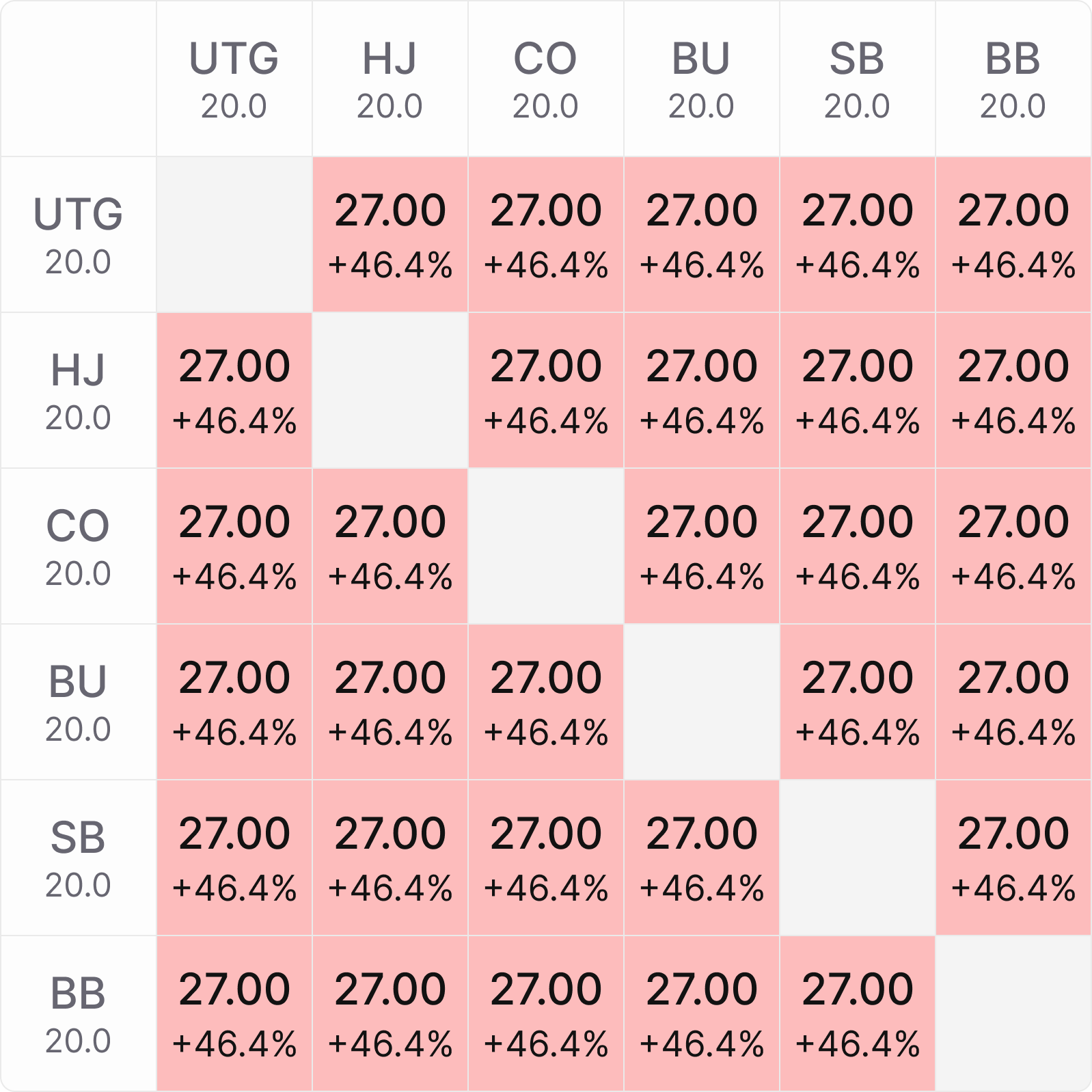

Now let’s go in the opposite direction and examine a steep payout structure:

The Bubble Factor is 1.35, meaning our players would need 57% equity to get all-in against each other. A small difference compared to the Standard payout structure, but a 3% difference between Flat and Steep, which is significant.

You may think the differences are quite small, so let’s use a more extreme payout structure. For example, what if this were a winner-take-all tournament?

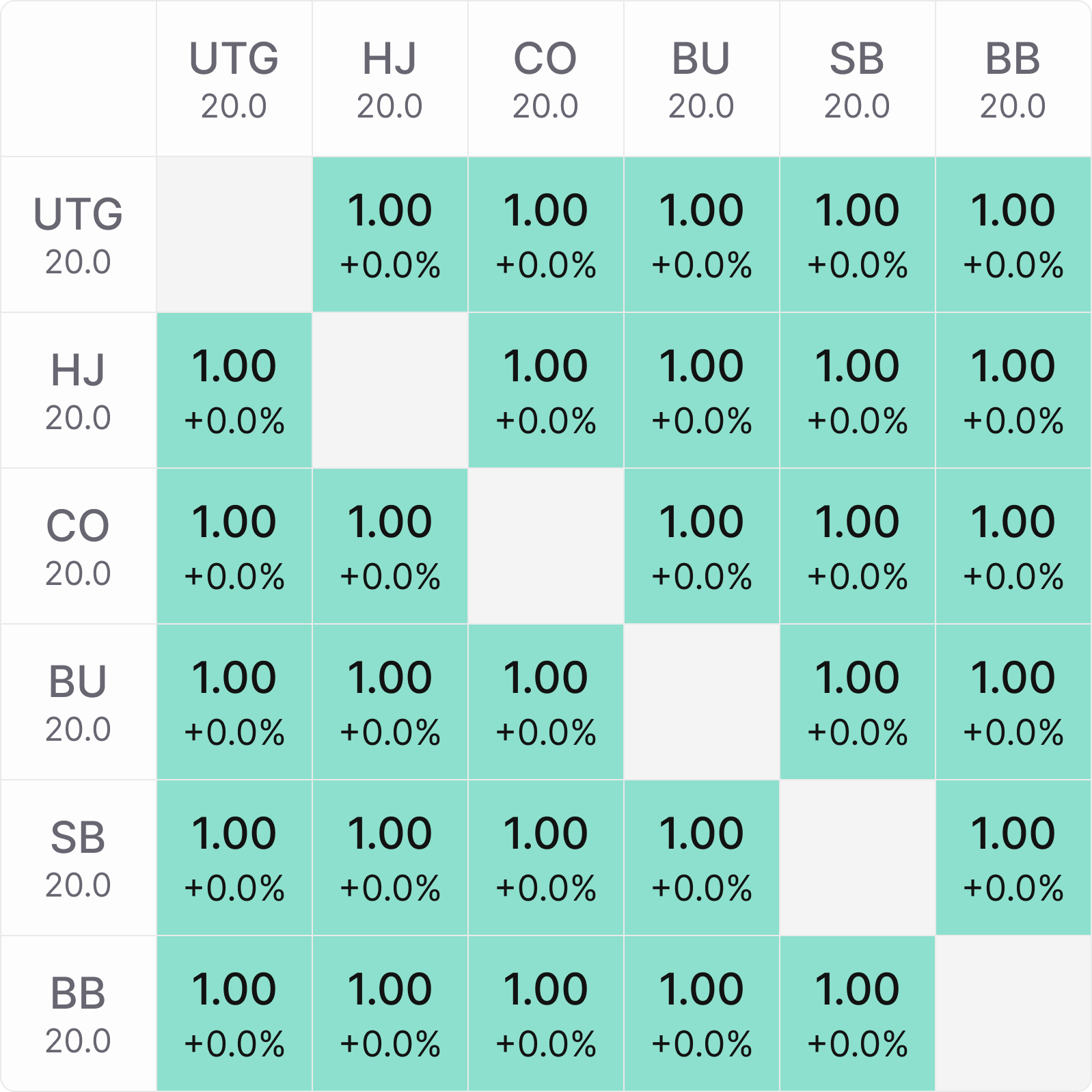

At the other end of the spectrum, what if this were a satellite that paid 27 players the same prize?

The Bubble Factor is 27, which is so extreme that you would need 96% equity to call an all-in. Spoiler alert: no hand has that much equity preflop. This is literally a situation where if everyone was playing GTO, UTG could shove all-in with 72o, turn their hand face up, and the BB still should fold Pocket Aces!

We should play tighter in a flat payout structure because guaranteeing cashing is more important. We should play looser in steep payout structures because winning the tournament is more important.

Payout structure and variance

We have looked at the difference in Bubble Factors and, therefore the strategic differences between flat and steep payout structures. The next game selection consideration is variance.

Using a tournament variance calculator, we can show how different the luck factor is when you compare the different payout structures.

In each of the following examples, we simulate how a player with a 10% ROI in $50 MTTs would fare, playing 1,000 MTTS with 100 runners. The only difference is the payout structure. We were not able to simulate Flat vs. Steep payout structures in the way we did with Bubble Factors. This time we have flattened or steepened the payout structure by changing the number of players who get paid.

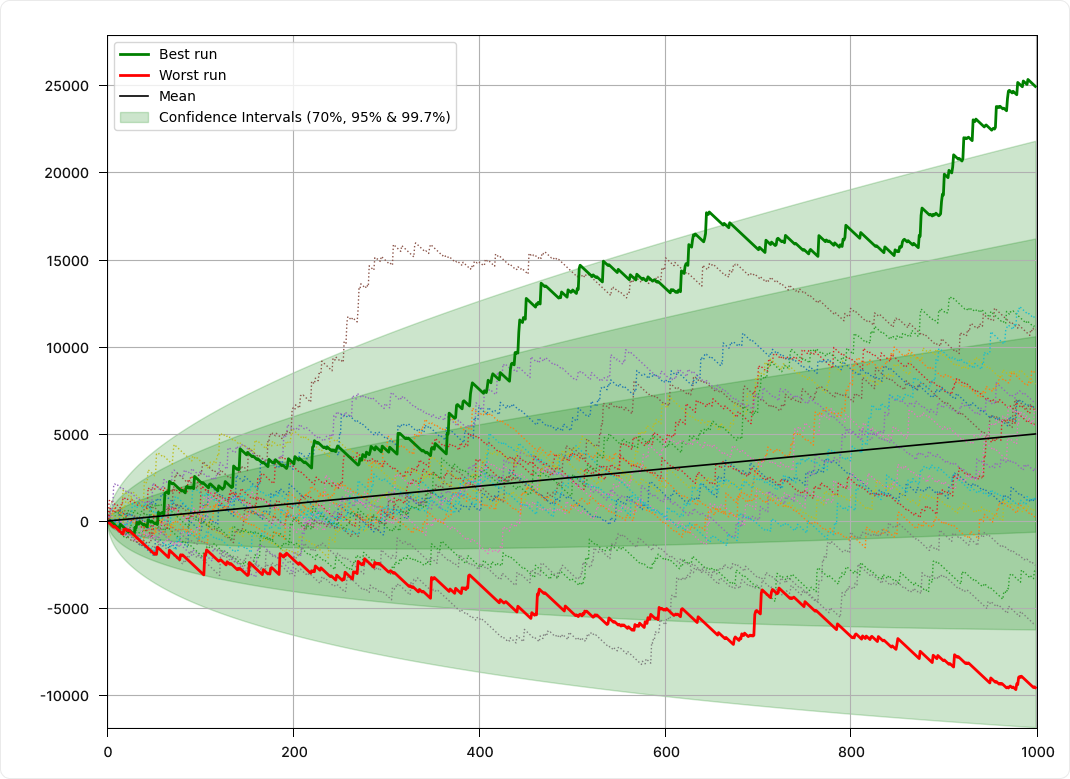

First of all, we simulated a standard payout structure by paying 15 of the 100 players. Here are 20 sample runs in the simulations we did.

In the best case, our player won around $25k, in the worst case they lost about $10k, averaging $5k profit. In this example, they had an 18.2% probability of loss and the required bankroll was $9,840 for a 1% Risk of Ruin.

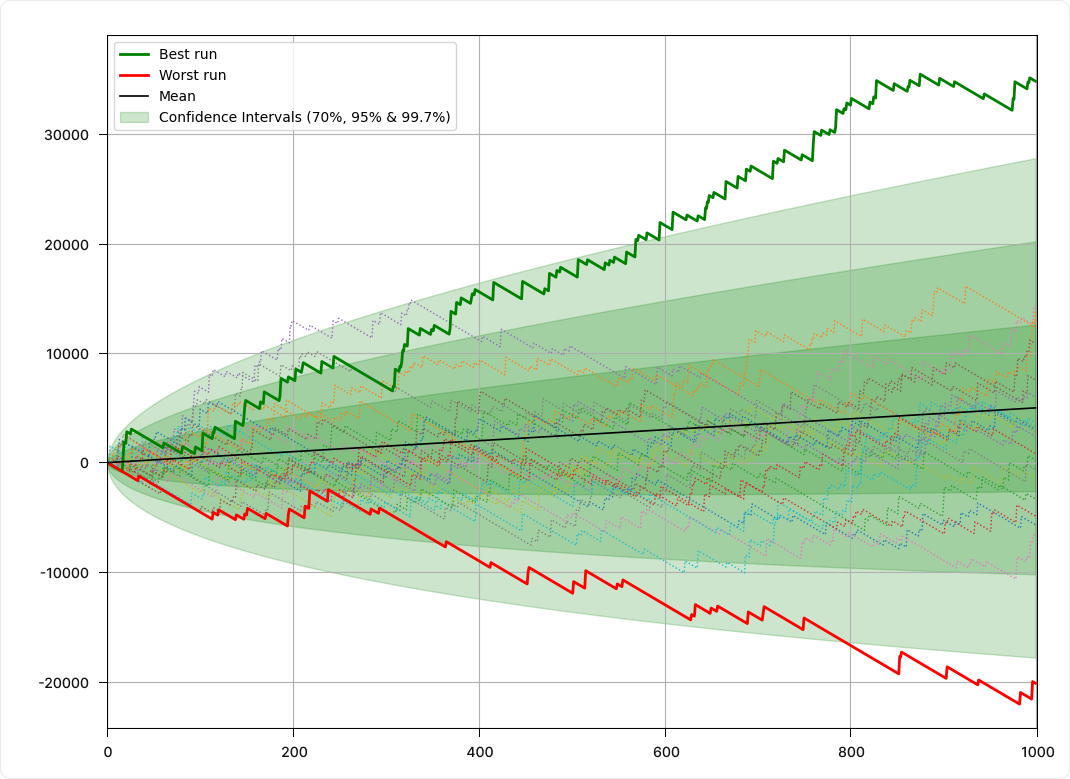

We reran the simulation, the only difference being only five people out of the 100 made the money in each tournament:

The best run was much better, making around $35k. The worst run was much worse, losing almost $20k. The average was similar, around $5k profit. This time there was a 26.1% probability of loss and a required bankroll of $14,275 – much more than the first example.

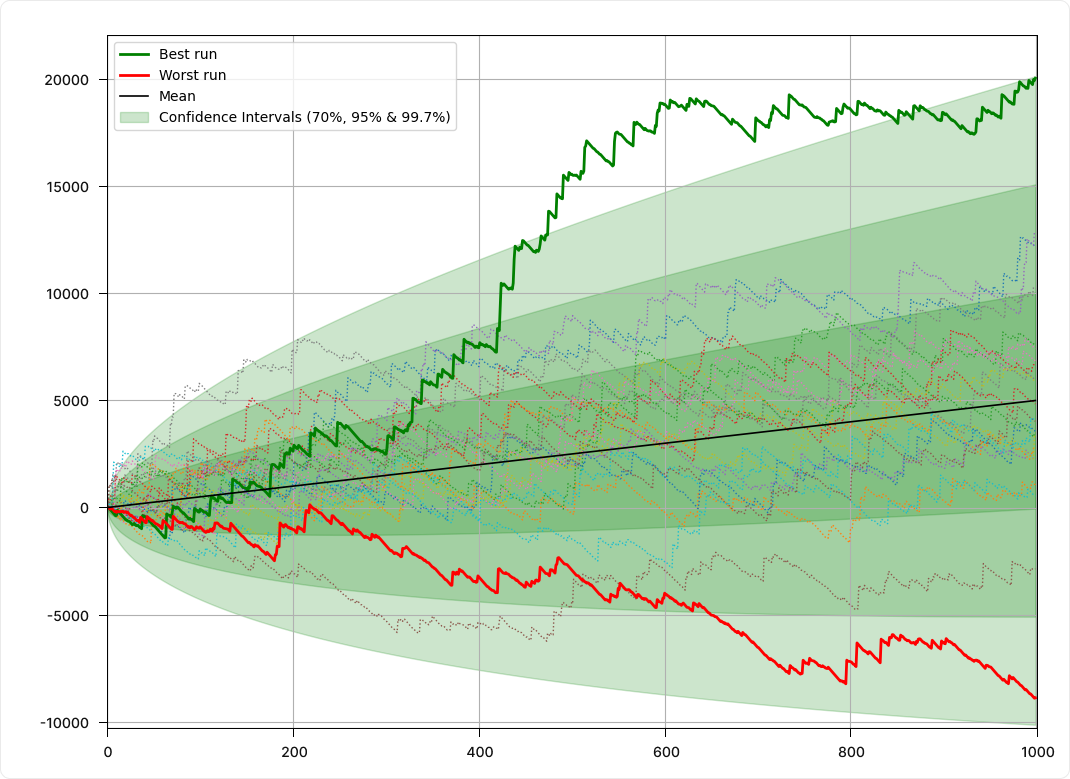

Finally, we simulated a flat payout structure by paying 30 of the 100 players in each tournament:

In this example, the best run made $20k, and the worst run lost just over $7k. The average profit was just over $5k. The probability of loss was 14.4% and the required bankroll was $7,797.

The Expected Value in every simulation was $5,000. That is what you would expect in a $50 MTT with a 10% ROI playing 1,000 tournaments (it is literally $5 per tournament, multiplied by 1,000). Over the long term, our player would make the same amount regardless of the payout structure. Because we are humans without infinite time to play, there are real game selection considerations here. Steep payout structures have the biggest short-term upside but also the greatest short-term downside.

You are much more likely to go broke specializing in top-heavy payout structures. Flat payout structures come with much less risk of loss, but their upside, by comparison, is capped.

Registration considerations

Payout structure impacts another key factor in game selection and ICM, which is when you register. We already covered this briefly in our article on late registration, but let’s play a quick Toy Game to highlight it here.

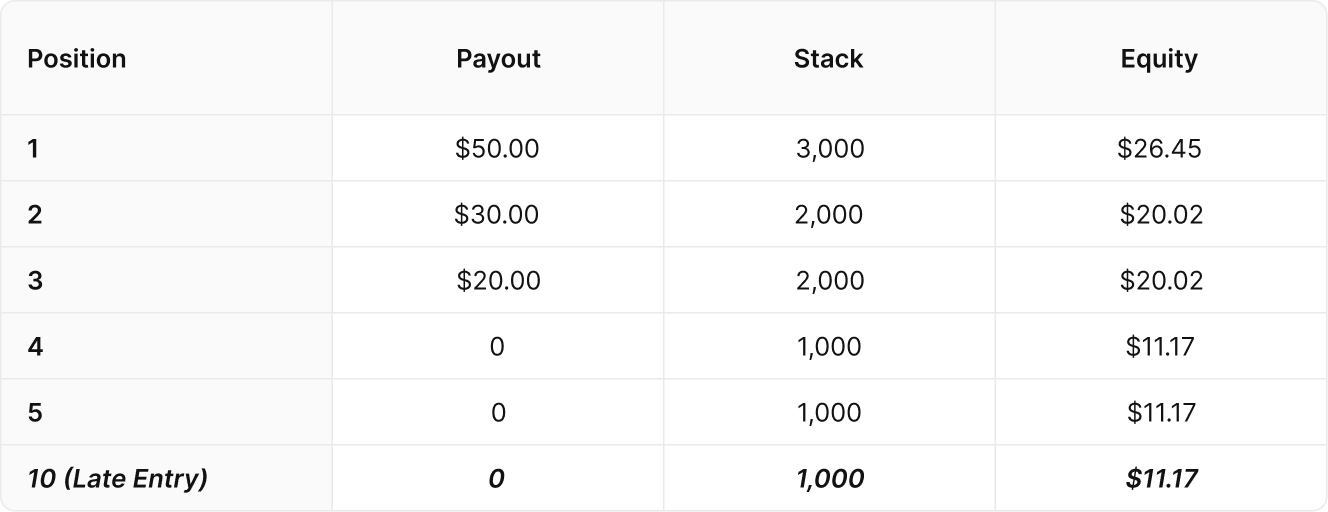

Let’s say we are playing a nine-person tournament, with $10 entry fees and 1,000 starting stacks. Four players have busted and we, the 10th player, register late. Let’s look at the ICM equity boost we get for registering late.

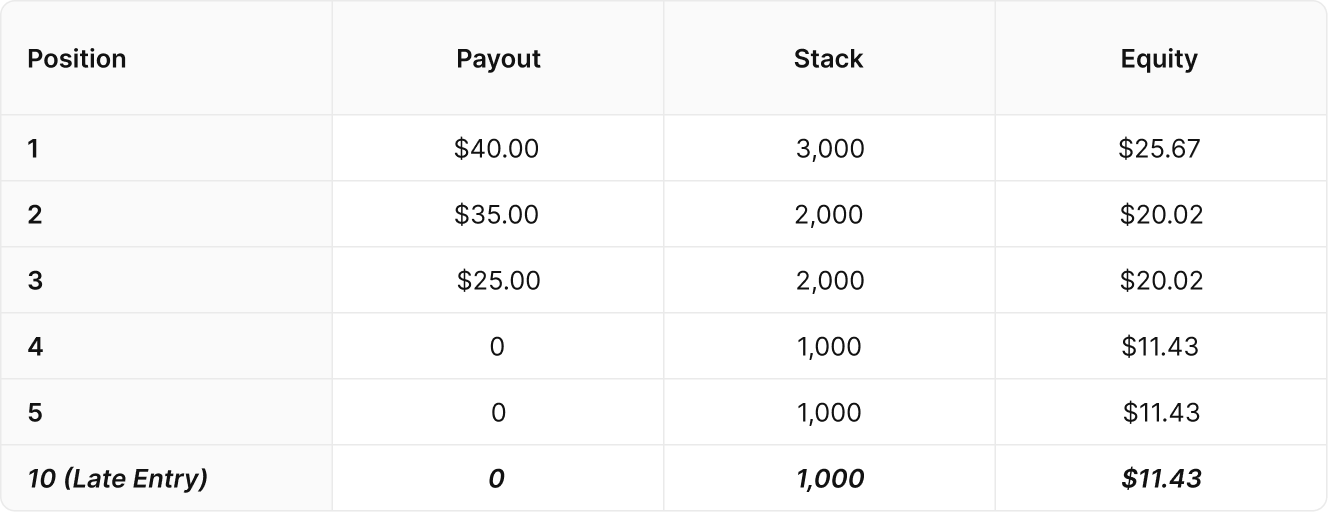

First of all, here is a standard SNG payout structure:

We are the 10th player at the bottom of the table. As you can see by late registering, we have received an instant equity boost of $1.17, or 11.7%.

What if we made the payouts flatter? The stack sizes are the same, but we took $10 from 1st and gave each of the other two payouts a $5 increase:

Our stack is worth more than in the first example, this time we get an $1.43 equity boost.

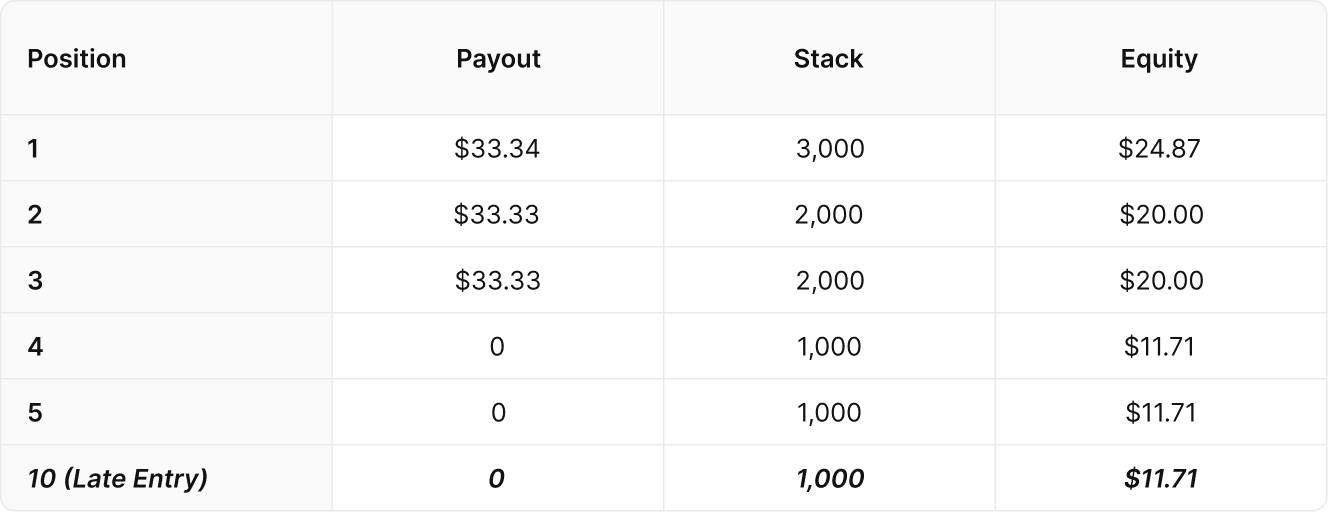

At the other end of the spectrum, what if we took some money from 3rd and gave it to the eventual winner, making the payouts more top-heavy?

Late registering is still profitable, but less so than in the previous examples. We only get a $0.99, or 9.9%, equity boost.

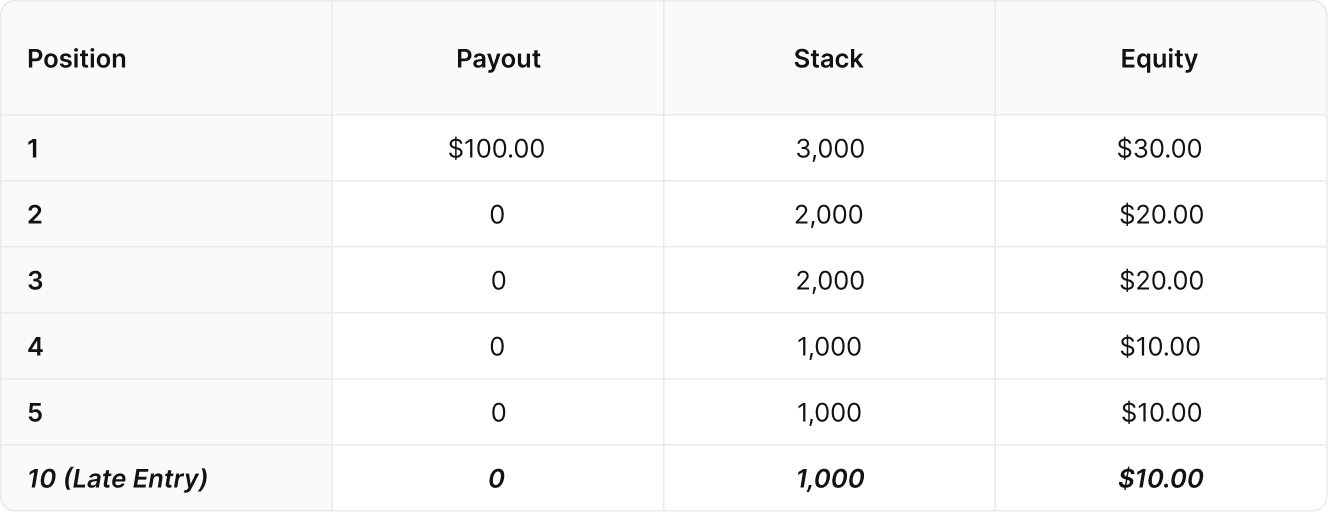

Going to the extremes, what about if this were a satellite paying three places?

Here we have seen the biggest boost of all, $1.71, just for buying in late.

You can probably see where we are going next, what if it were a winner-takes-all tournament?

As we stated in the last example, a WTA tournament is ChipEV, there is no bubble and, therefore, there is no benefit to registering late. Our $10 is still worth $10, regardless of when we register. For that reason, assuming you are a skilled player, it is probably best to enter these tournaments from the start.

There is a very important ICM lesson here where payout structures are concerned.

When you late register for most tournaments, you will make more money overall, but you will win it outright a little less often than if you registered at the start, assuming equal skill.

The flatter the payout structure, the more valuable it is to register late because mincashing is the immediate priority. When a tournament has a top-heavy payout structure, winning the whole thing is more important. It is still profitable to late register most steep payout structures, but buying in early if you have an edge with deep stacks might be a better decision.

Complicating factors

All of our examples today have not only assumed equal skill between participants, but they also assume equal incentives. In real life, there are often complicated nuances that change the dynamics. Not everyone is playing for the same amount of EV in the same tournament.

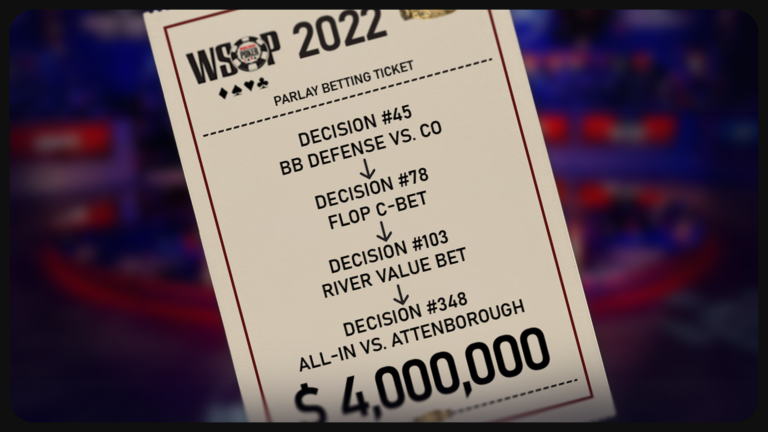

For example, for the last two years, GGPoker has had a promotion for online qualifiers in the WSOP Main Event. Win the Main Event wearing the GGPoker patch, and you get an extra $1 million. This is precisely what happened with Espen Jorstad in 2022. In previous years major poker rooms like PokerStars have awarded sponsorship to their qualifiers for making the WSOP final table.

Let’s say the top prize at the WSOP Main Event final table is $10 million, but there is a player who qualified for it at GGPoker still there. They are playing for $11 million, while everyone else is playing for a maximum of $10 million. If they come 2nd they win the same prize as everyone else would for being runner-up, but if they win it they win 10% more. They are playing for a steeper payout structure than is advertised.

Likewise, some promotions flatten payout structures, in a manner of speaking, for some players. Leaderboard promotions, for example. A famous example was in 2019 when Robert Campbell won the WSOP Player of the Year leaderboard, but the WSOP calculated the points incorrectly. Shaun Deeb thought he needed a big final table finish to take the lead in the final event, so he played for the win. It only transpired later, after the error was discovered, that he needed just a relatively small final table finish to win it. Deeb said later he would have played really nitty had he known and probably would have laddered to the title.

Likewise, some promotions flatten payout structures, in a manner of speaking, for some players. Leaderboard promotions, for example. A famous example was in 2019 when Robert Campbell won the WSOP Player of the Year leaderboard, but the WSOP calculated the points incorrectly. Shaun Deeb thought he needed a big final table finish to take the lead in the final event, so he played for the win. It only transpired later, after the error was discovered, that he needed just a relatively small final table finish to win it. Deeb said later he would have played really nitty had he known and probably would have laddered to the title.

In this example, the min-cash and laddering was worth more to just one player, Shaun Deeb, in the final tournament. Deeb was playing a flatter payout structure than everyone else, though he didn’t realize it, because each ladder was worth so much more to him. Because of the error by the WSOP, he instead played like he was playing in a steeper payout structure.

We see this effect when somebody has a bracelet bet at the series. There are some players, also, that simply value the bracelet more than the money, and are happy to bubble more often for a big stack. Finally, there are some players for whom the money is more important. Either they really need to lock up a mincash, or they really need the first prize money.

The point is that, in real life, we can’t assume everyone is playing for the same payout structure as we are. We can’t assume they will make the big laydown in the flat payout structure because they might have made a prop bet that they will win the whole tournament, or coming third might get them out of makeup. We might also be able to exploit the player in the steep payout structure on the bubble because they qualified via a satellite and the mincash means so much more to them.

Conclusion

The ICM differences between flat and steep payout structures are in many ways parallel with the differences between small and large fields. Flat payouts are like small-field tournaments, there is less incentive to play for the win and more incentive to secure a money position. In both instances, the smaller payouts are a bigger proportion of the overall prize pool.

Steep payout structures are like large field tournaments. More of the prize pool is in the final money positions, and the min-cashes are worth less, so there is more incentive to play an aggressive style of chip accumulation. This also means that late registering is more profitable in flatter payout structures.

Like small fields, there is less variance in flat payout structures because you are more likely to walk away with a meaningful prize. However, the upside of these tournaments is capped. Steep payout structures, like large fields, have much more variance because there is more impetus to finish in the top 1% of the field.

Steep payout structures are like large field tournaments. More of the prize pool is in the final money positions, and the min-cashes are worth less, so there is more incentive to play an aggressive style of chip accumulation. This also means that late registering is more profitable in flatter payout structures.

Like small fields, there is less variance in flat payout structures because you are more likely to walk away with a meaningful prize. However, the upside of these tournaments is capped. Steep payout structures, like large fields, have much more variance because there is more impetus to finish in the top 1% of the field.

The strategic differences between a normal payout structure, and one that is a tiny bit flatter or steeper, tend to be quite minor. However, the difference between flat and steep is quite significant. More importantly, the payout structures at the extremes, like satellites and winner-take-all tournaments are so significant they are essentially different games entirely.

Author

Barry Carter

Barry Carter has been a poker writer for 16 years. He is the co-author of six poker books, including The Mental Game of Poker, Endgame Poker Strategy: The ICM Book, and GTO Poker Simplified.