How To Negotiate Final Table Deals

Most people’s first introduction to the Independent Chip Model (ICM) is not from studying bubble play or endgame ranges; it is their first time making a big final table. This is when deal-making is proposed, and ICM is first introduced. Understanding ICM is particularly important when making final table deals, and making an error in this department can be very costly.

Why Make A Deal At Final Tables?

ICM was first introduced to poker to negotiate final table deals. It began life as the Mason-Harville Formula in 1987. David Harville created a model for making horse racing predictions in 1973, and Mason Malmuth adapted it for final table deals. The model would estimate how likely each remaining player was to finish in every position based on the percentage of chips they had. The chances of each player coming 1st was the percentage of total chips they held, but every other position was much more complex to calculate. Only much later in the modern poker era was ICM used to guide strategic decisions.

There are lots of excellent reasons to deal at a final table, including:

- To save time by not playing the final table at all

- To guarantee a specific prize amount

- To guarantee you win the trophy

- To reduce variance

The final reason is at the core of why most people deal.

We make deals to reduce variance when we reach big final tables.

There are opportunities in poker that don’t come around very often, like if you make a final table with many runners and/or you qualified via a satellite. You don’t know when you’ll make the next 5,000+ runner final table. If third place prize money would double your bankroll, get you out of makeup, allow you to move up stakes, pay for a house or otherwise change your life positively, there is no need to needlessly subject your current equity to variance.

If you are happy with the prize, there is no such thing as a bad deal, but when you understand the mechanics of final table deals, you put yourself in a better position to negotiate for your own self-interest.

Chip Chop Deals

A Chip Chop deal simply takes the remaining prize pool and awards money to the players based on the percentage of chips they have. As you can imagine, a Chip Chop deal is usually the one proposed by the chip leader.

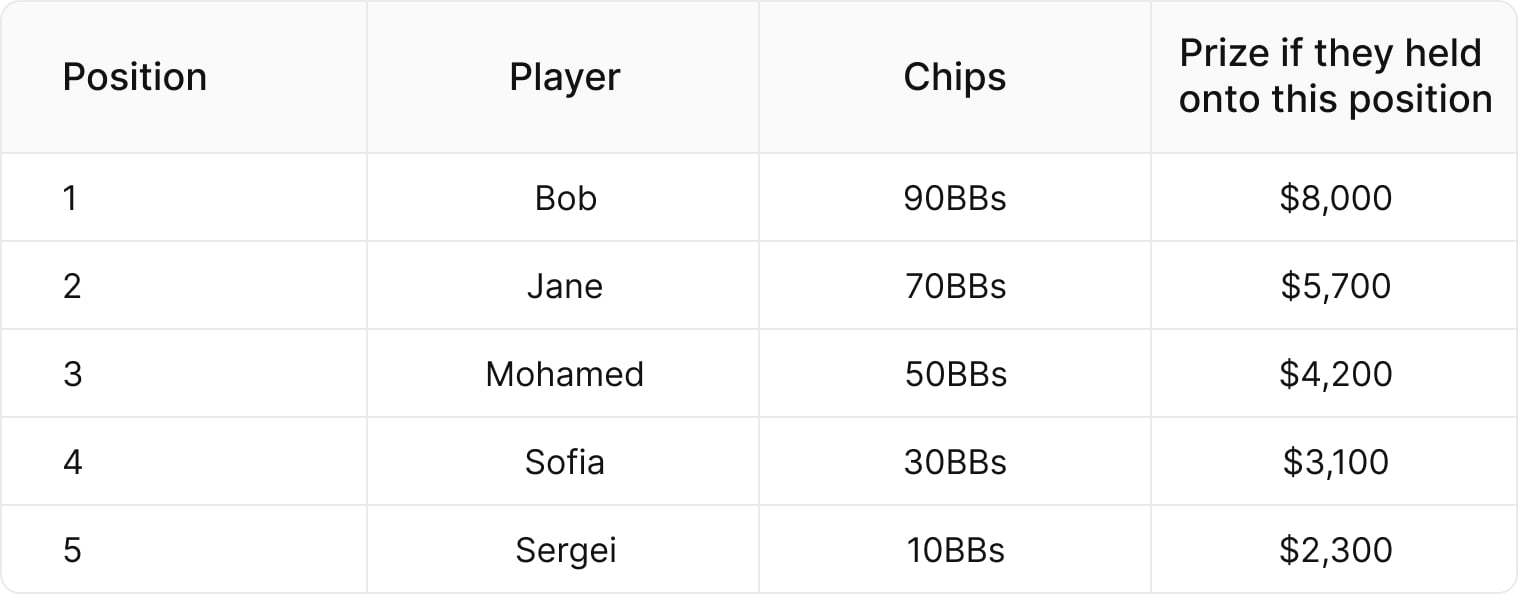

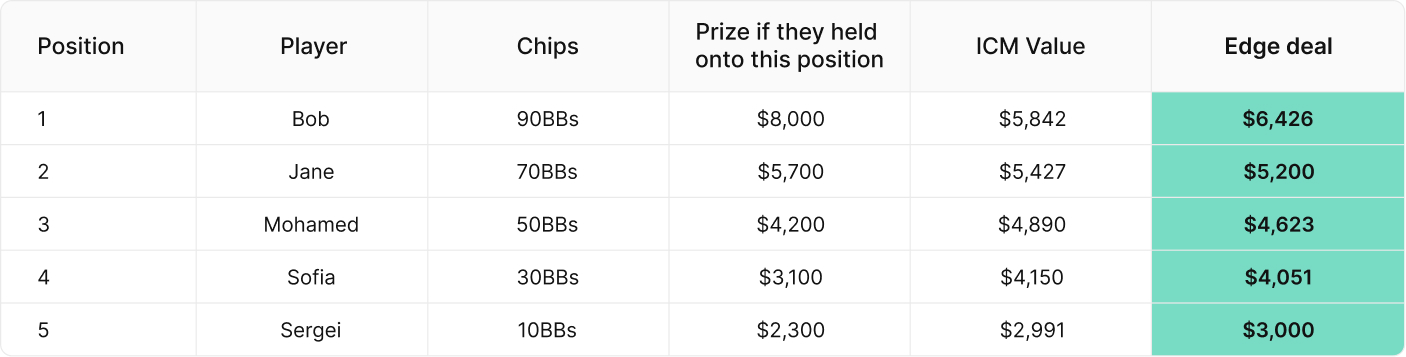

Let’s look at an example to highlight this type of deal. Below is a final table of five players, their chips, and what their prize would be if they maintained the position they are currently in:

There are two ways to potentially Chip Chop, the first one is literally just to take the remaining prize pool and split it between the players based on their chip stacks.

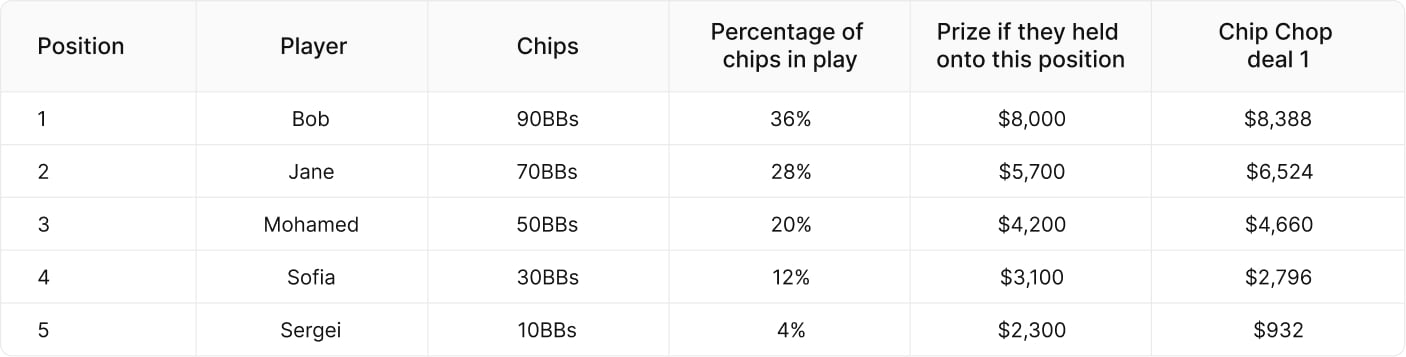

There is $23,300 remaining in the prize pool. Chopping it up that way would look like this:

You can probably spot the immediate issue with this type of deal. Not only has Bob managed to secure a prize more than first place prize money, Sergei, the short stack, takes home less than half of what he was guaranteed to take with no deal in place.

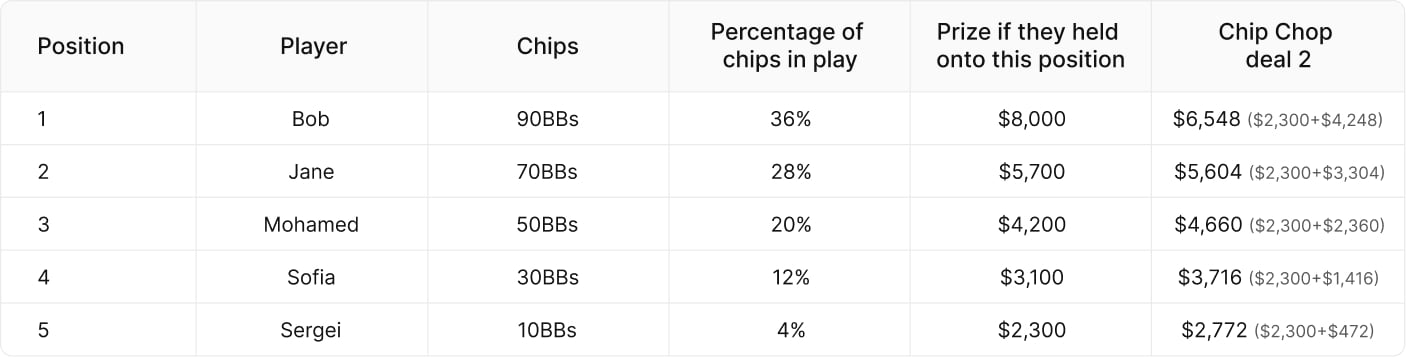

This type of Chip Chop is clearly a bad idea, so what typically happens is a Chip Chop deal based on the percentage of chips, but after everyone has locked up the min-cash. So in this example, everyone would take home $2,300 and deal based on the remaining prize pool, which would be $11,800. Such a deal would look like this:

On the surface, this looks like a favorable deal for all parties. The bottom three stacks have all secured more than their projected finish position would pay them, Jane barely sacrifices any of her 2nd place prize money to lock it up, and Bob takes the biggest hit but still locks up a lot more than 2nd place.

ICM deals

The ICM Deal is the alternative to the Chip Chop deal and is the gold standard for final table deals. ICM has limitations as a strategy and also in final table deals:

- It doesn’t account for skill. ICM assumes all the players are of equal ability.

- ICM ignores blinds increasing. If you know the blinds are about to increase, that can affect the optimal strategy, especially with shortstacks involved.

- ICM doesn’t factor in table dynamics. For example, being seated next to an aggressive chip leader can be a nightmare to play.

The only thing an ICM deal considers are the payouts and the stacks of the remaining players.

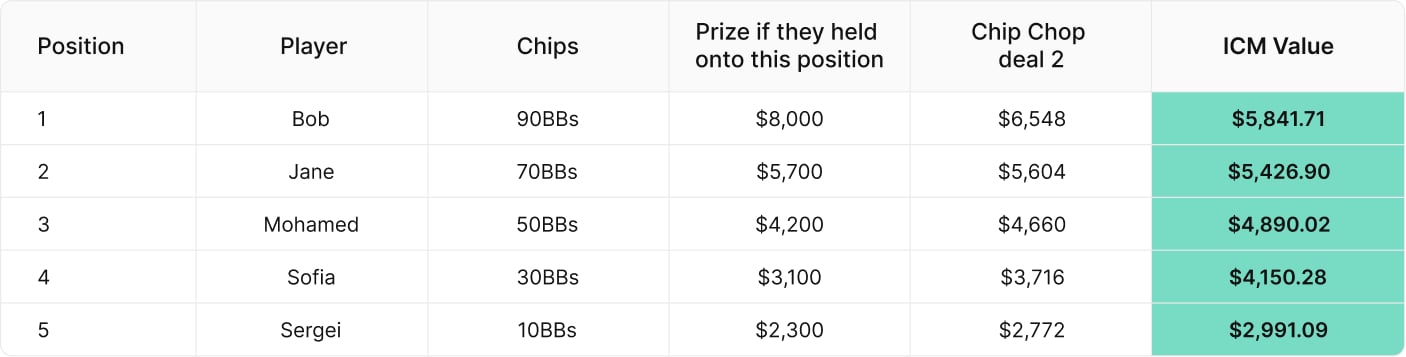

Let’s go back to our first example and look at it through the lens of ICM instead. Below is the exact same final table but with the ICM value of each stack. We have also added the Chip Chop value from the previous table so you can compare the two:

You can see why a chip leader favors the Chip Chop deal, it is worth $706.29 more to them. Jane, second in chips, also does slightly better with Chip Chop. That money comes from our three short stacks, who are all between $200-$300 worse off with the Chip Chop deal.

Two things always strike players who first encounter ICM when they are making final table deals:

The big stack is always worth less than most players think, the short stack is always worth more than most players think.

The key takeaway here is that ICM deals favor shorter stacks. This is a core principle of ICM, the fewer chips you have, the more each one is worth. In this example, one big blind is worth $299.11 to the short stack, but only worth $64.91 to the chip leader.

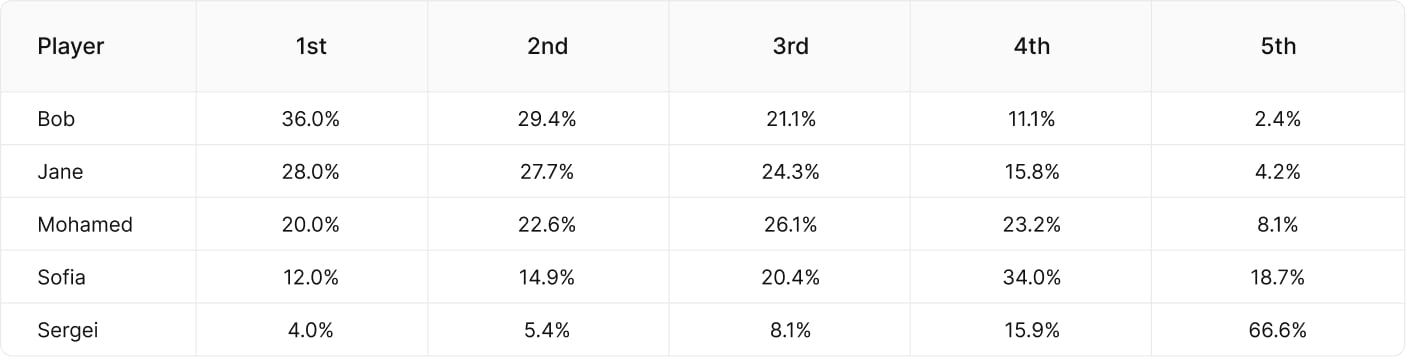

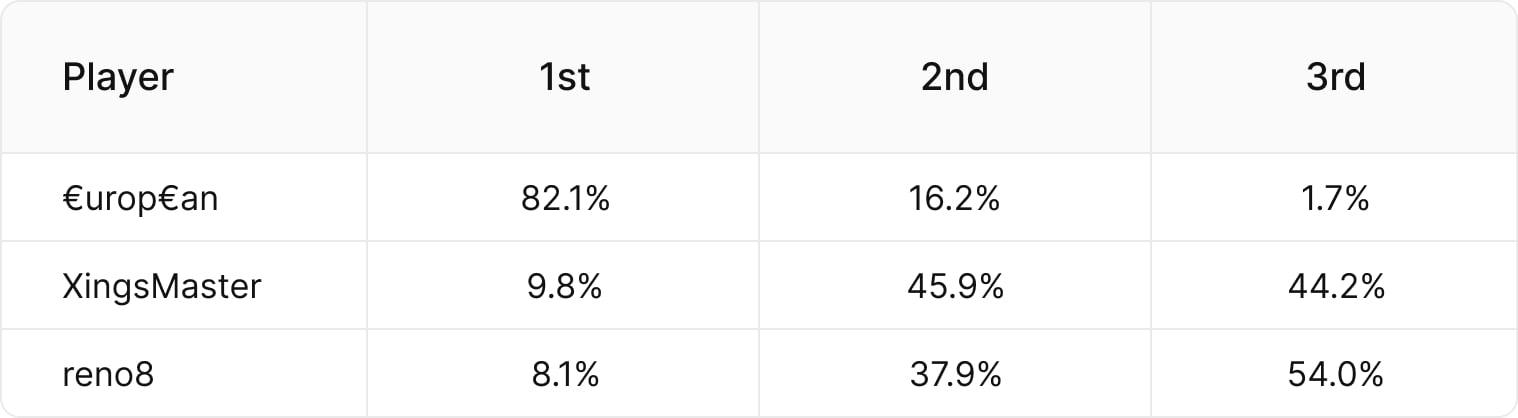

If these payouts seem wrong or unfair to you, let’s explore them further. Below are the projected finish distributions based on the ICM model for this final table, if no deal was struck:

Bob wins it more than anyone else, but 64% of the time he doesn’t come 1st, making a Chip Chop deal for more than 2nd place prize money unfair. Sergei busts next most of the time, but 33.3% of the time he manages to ladder to a prize of at least $3,100, so he needs to get something to encourage him not to play on to try and spin up.

Only the big stacks benefit from a Chip Chop, and it is at the expense of everyone else.

A short stack is worth more and ladders more often than a Chip Chop deal would suggest. A Chip Chop deal makes sense only when the final two players are heads-up. There is no ICM heads-up and you could, therefore, give each player 2nd place prize money and then chop up the remaining money equally based on their stacks at the time.

Skill deals

The biggest flaw with the ICM model in terms of final tables is it does not factor in skill. Few professionals would want to give a bad player a deal assuming equal skill. Likewise, elite players would not want to sacrifice edge. ICM deals work because the edges are quite small at most final tables, especially with shallow stacks or a fast structure. The difference between two good regulars will be minimal, so unless there is a big gulf in class between the players, an ICM deal is better than subjecting oneself to variance.

When one player shines above the rest, they can negotiate a final table payout based on their perceived edge. This would involve using ICM as a baseline after the elite player has taken a markup from the remaining prize pool. In our example above, let’s assume that our chip leader Bob is a professional player with an edge over the others. He estimates his edge is 10%. What he might propose is that he takes a 10% markup on the ICM value of his stack, while everyone else at the final table negotiates amongst themselves based loosely on ICM. Usually, it would be the other big stacks taking the hit to secure a payout because the short stack has less to lose by refusing.

This sort of deal is part science, part negotiation, with some art thrown in. Such a deal might look like this:

Getting better than 1st place prize

In rare cases, an excellent player can negotiate a deal where they take more than the projected first prize. They either have such an edge that can dictate these terms, or the other players are so scared of busting next that they agree to poor terms. A great example was when online beast ‘€urop€an’ won the 2016 WCOOP Super Tuesday. He had both an enormous chip lead and is also regarded as one of the best online tournament players of all time.

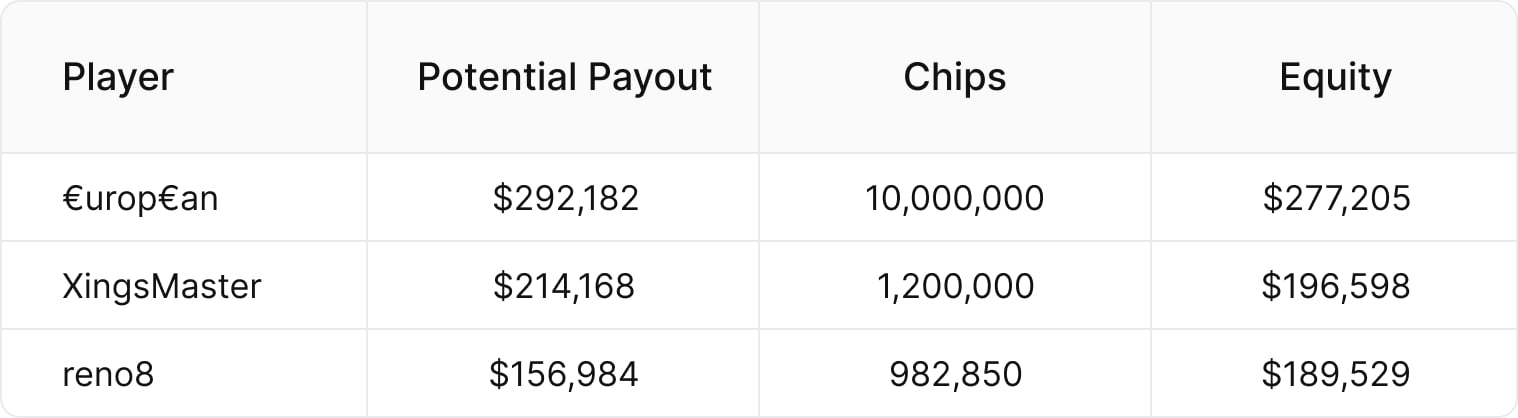

This is how things stood when the deal was proposed, with the potential payouts as they were (the chip stacks are not exact but the last way each one was reported during the event):

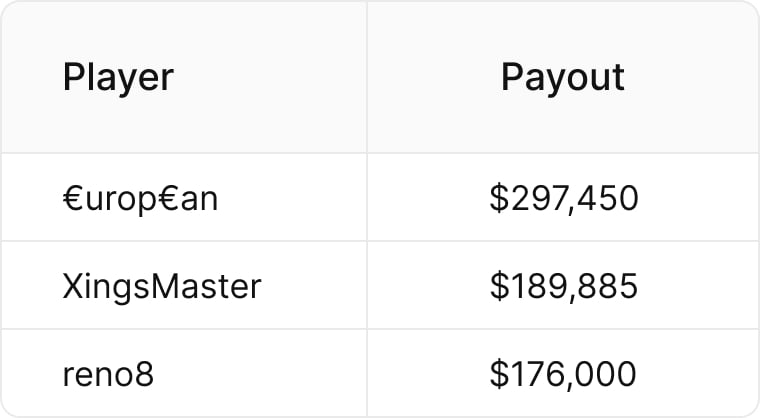

However, €urop€an managed to negotiate this deal:

He secured $5,268 more than the official first place payout! In exchange for this, ‘XingMaster’ secured $32,901 more than what 3rd would have got, but $24,283 less than what he would have won for finishing second. ‘reno8’ won $19,016 more than he would have for his third place finish. If this were an equal skill matchup then amazingly €urop€an only had $277,205 in equity despite a 10-to-1 chip lead. Assuming equal skill this is what ICM says would be their likely finish position chances:

Then you have the matter of edge which is not insignificant here. It actually doesn’t look like a terrible deal on the surface. XingsMaster and reno8 essentially are playing a pseudo heads-up match for $57,184 (the difference between 2nd and 3rd place prizes) and have paid €urop€an $5,268 for the privilege of splitting $51,916 amongst themselves.

€urop€an only winning 82.1% of the time might surprise some people and would lead them to argue that it is worth the other two players not dealing. The problem for the other two players is that both of them don’t win 90% of the time.

Deal-making mindset issues

Beyond the numbers, there are several mindset issues that can lead a player to reject a good deal or accept a terrible deal.

- First of all, there is the anchoring effect of the money itself. Some players might have looked at what 3rd place prize money would do for them personally (a new car, moving up stakes, a holiday, etc.) and are unwilling to look beyond that. Others will look at their position in the tournament and be unwilling to give up what their potential prize would be if they maintained their position.

- There is also a social pressure element to final table deals. It might be that you do not want to give the arrogant professional player $500 more than ICM because he has suggested he has an edge on you. On the flipside, it is easy to get bullied into a bad deal for fear of being ostracized by the other players. You will have a sense of where your own mindset issues will lie in this regard, but perhaps the best way to ensure you do not get pressured into a bad deal is by understanding ICM in the first place.

If the social pressure is too much, an easy hack to push for a good deal or refuse a bad deal, without social stigma, is to just tell the other players you have a backer who has insisted on your terms.

You can make this fictional backer the bad guy while still enjoying the final table camaraderie with the other players.

Conclusion

Even if you play on a site that doesn’t facilitate final table deals, it is a good use of your time to study them. Studying final table deals and understanding the value of your stack will help with strategic decisions, particularly where Bubble Factor is concerned. Understanding the ICM implications of final table deals puts you on a good footing for that once-in-a-lifetime final table you may find yourself on one day in your career.

Key Takeaways

- There are lots of good reasons to deal, most notably reducing variance

- Chip Chop deals benefit big stacks at the detriment to short stacks

- Short stacks are worth more than people think in ICM deals

- Big stacks are worth less than people think in ICM deals

- ICM deals assume equal skill

- Edge deals are rare and there should be a big gulf in skill to consider them

Author

Barry Carter

Barry Carter has been a poker writer for 16 years. He is the co-author of six poker books, including The Mental Game of Poker, Endgame Poker Strategy: The ICM Book, and GTO Poker Simplified.