The Many Faces of Balance in Poker

When you think of balance in poker, what comes to mind?

Most likely, you were introduced to the concept by the relationship between bluffing and bluff-catching. If your betting range is imbalanced—if you bluff too much or not enough, relative to the number of value hands you could have in a given spot—then your opponent can exploit you by bluff-catching more or less. Conversely, if they bluff-catch too much or not enough, you can exploit them by bluffing less or more.

This is a great introductory example of how balance functions because it is simple, clean, and straightforwardly calculated (on the river, anyway). It’s easy to see the relationship between your strategy and your opponent’s, and how an imbalance on one side of the scale incentivizes the other player to be imbalanced as well in order to exploit the deviation.

This is just one simple example of balance, however. Many other such relationships exist, operating behind the scenes. And, as they all play a part in shaping the equilibrium strategies returned by solvers, they can also be used to explain why the outputs look the way they do, with so many different hands mixing at specific frequencies.

Most of them, however, are not as easily calculated as bluffing and bluff-catching frequencies, so the goal of this article is not to solve them precisely (you wouldn’t be able to do so during in-game situations anyway) but simply to understand the relationships so that you can think more deeply about vulnerabilities in your strategies and those of your opponents.

Early Streets

Before the river, most hands can not be neatly classified as “bluff” or “value.” Colloquially, we may categorize a hand as a bluff, but for a deeper understanding of its true nature, it’s important to recognize the following fact:

A hand’s ability to still win the pot if called, whether by improving or bluffing again, is an important difference from river bluffs.

The general relationship between bluffing and bluff-catching still exists on earlier streets, but the ratios do not usually work out so cleanly because hands are not as clearly defined. There is also a new balance to consider when betting or facing a bet:

Because hands can change value, there is some incentive for a player facing a bet to raise with bluff-catchers rather than calling, as they would on the river.

The reward of raising bluff-catchers is that it enables them to deny equity or get additional value from draws and perhaps even to push the opponent off a better hand that was itself betting for thin value and protection.

The risk of raising bluff-catchers is that it could mean putting in money when way behind against the top of the bettor’s range and missing profitable bluff-catches against the bottom on future streets.

GTO betting ranges usually consist of:

- A more polar component of hands, which do not mind getting raised (strong hands are happy to continue, very weak hands lose little beyond the initial bet when they fold), and

- A more linear component of hands, which benefit from folds, do not mind getting called but hate getting raised.

These linear hands include both semi-bluffs and thin value-bets from non-nut hands, many of which will not be strong enough to bet again on future streets but can benefit from denying equity while still having a reasonable chance of winning when called.

An overly polar betting range offers the opponent little incentive to raise. An overly linear betting range offers little incentive to call.

The balance between the polar and linear components corresponds with the balance between the opponent’s calling and raising frequencies.

Board Coverage

“Board coverage” is a nebulous concept that, although related to balance, is harder to quantify. Essentially, the way to achieve board coverage and the motivation behind it comes down to the following:

In any non-folding range (betting, checking, calling, raising), players are incentivized to include a variety of hand types so that they will not be overly predictable on future streets.

For example, if there are two hearts on the board (♥♥X), it will generally be correct to have flush draws in both your betting and checking ranges so that your opponent cannot confidently value-bet non-flush hands on the next street that brings a third ♥ no matter what your action is on the current street.

It will also generally be correct to have other weak hands besides flush draws in both ranges, so that you have something to bluff with when the flush comes in. I first learned this concept from Alex Sutherland, who has an excellent demonstration on his now-defunct GTO Range Builder blog.

The amount of money your opponent will put into the pot on future branches of the game tree determines your incentive to arrive at those branches with certain hands. This is related to the concept of “implied odds”—the incentive to call with a drawing hand despite not getting the right immediate odds because of additional bets you could win if the draw comes in—though it is more complex than that. Taking weak hands to future streets can be correct not only because they may over-realize equity by value-betting when they improve but also because they may over-realize equity by bluffing when they don’t improve.

This can only be taken so far, however. Not even solvers can profitably design strategies that will be perfectly balanced on all possible runouts! Typically, they invest in balance for big classes of hands like flush and straight draws but do not find it worth the cost to invest in otherwise worthless hands just to balance around edge cases such as the one or two cards that complete both draws. In those rare cases, they simply accept that they are imbalanced and make the best of it.

Acting First on the River

The above concept applies not only on early streets but also when you are acting first on the river (or really, any time you are not closing the action). It is about future decision points, not necessarily future streets. But on the river, it is most often a consideration for the player acting first.

Because the out of position (OOP) player’s checks do not close the action, they have some incentive to check their strongest hands, to induce bets (such as bluffs and value-bets from worse) and then get in a raise. They also have some incentive to bet their strongest hands, to induce bluff- and value-raises from worse (in addition to getting calls from worse hands that would have checked).

The same can be said for the in position (IP) player, if they are using multiple sizes. They have some obvious incentive to bet big (often all-in) with their nut hands, but they also have incentive to bet smaller as a trap, hoping to induce raises from hands that would not have called a shove.

Much as on earlier streets, the ratio of traps to thin value is what determines the opponent’s incentive to raise as a bluff or for value with their own non-nut hands.

- Traps are hands that want to get raised.

- Thin value are hands that are ahead when called but lose EV when raised (because they will sometimes lose to bluffs when they fold and lose to strong hands when they call).

Facing a Raise Before the Flop

All the above considerations apply to preflop play as well, which is, of course, an early street. In fact, the difficulty of classifying hands as “bluff” or “value” is especially salient before the flop, where it’s tough for any hand to have more than 70% or less than 30% equity. The extra wrinkle before the flop is that, unless the action folds to the SB, you are potentially playing a multiway pot, and the whole idea of equilibrium gets tricky in multiway pots.

Suppose HJ opens, and you 3-bet from the CO. You’ve got a well-constructed range balanced around the concepts we’ve discussed above with a linear component incentivizing HJ to 4-bet and a polar component incentivizing HJ to call and a smattering of suited connectors so you’ve got something to bluff with on Broadway boards and something to stack off with on medium, connected boards. Then along comes the BTN and kicks over your precisely balanced scale with a cold 4-bet.

Your 3-bet range is still mostly balanced against the original raiser, determined mostly by how often they will call and 4-bet and how they will play after the flop, because they are by far the player most likely to contest the pot with you. But you are also constrained by the other players holding cards, which is why CO VPIPs more hands into an LJ open than HJ does and BTN VPIPs more still. They’re all facing the same original raise, but with more players remaining to act behind them, the earlier position players need stronger hands to contest the pot.

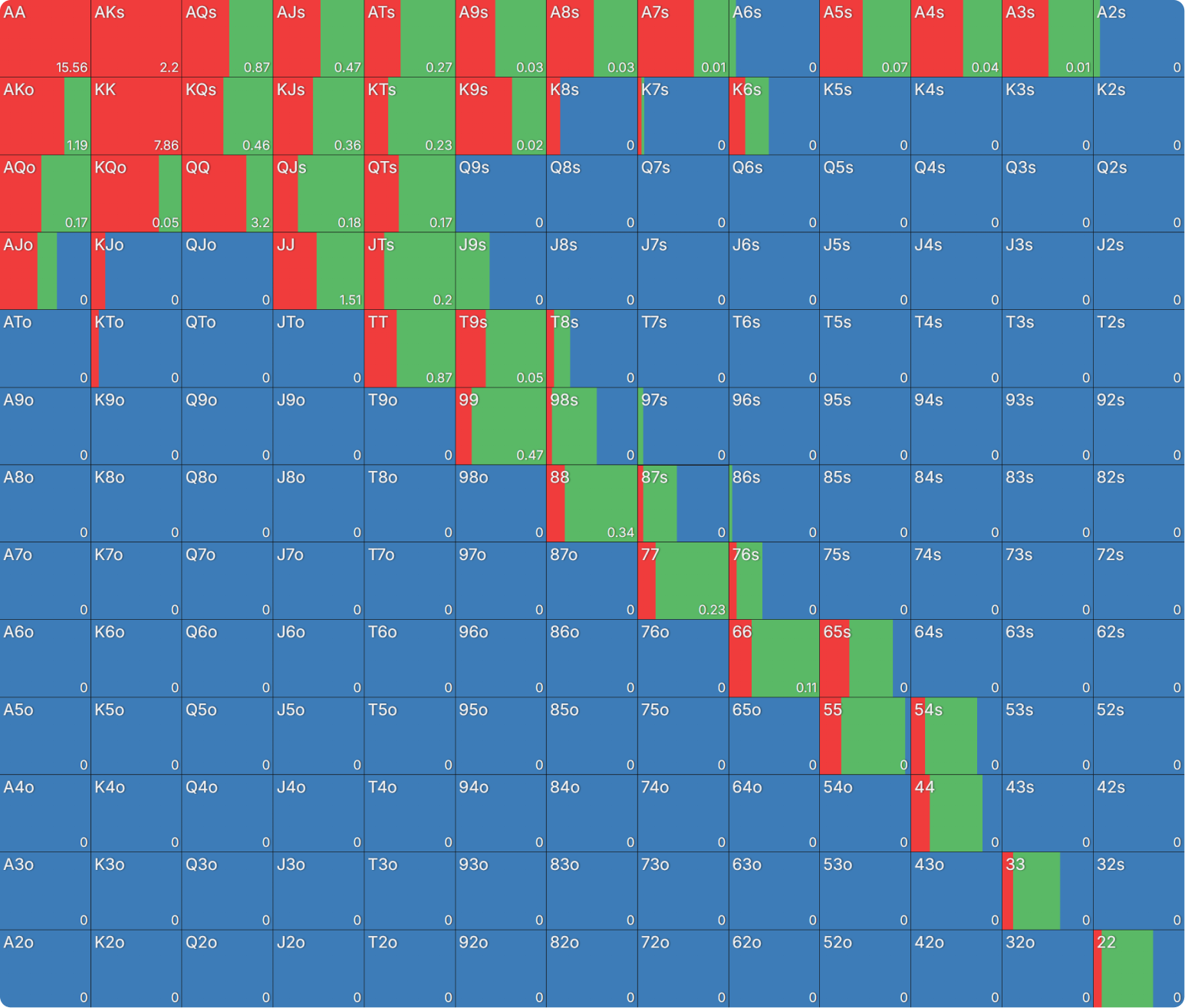

Response to LJ Raise, 100bb Cash

What’s all this got to do with balance and exploitability?

Suppose you’re in the CO facing a raise, and you know the BTN is an extremely tight and passive player who will fold far more hands than a solver would and rarely raise. Or, if you’re playing live poker, maybe you look left and see them preparing to fold their cards. In either case, you basically have the BTN and can play a strategy that involves a lot more calling than you would typically do in this spot (which is still not terribly much, to be clear!).

Conversely, if the BTN is overactive, you should be a bit tighter in the CO and favor a raise-or-fold strategy.

Playing Kingmaker

In heads-up pots, mixed strategies are all about balance.

When a solver mixes a certain hand between, say, bets and checks, that’s because there’s incentive to have that hand in both ranges.

If you show up with any type of hand too often in one range, your opponent could exploit you in some way.

This is not necessarily the case in a multiway pot, however. Notice how, in BTN’s response to a LJ raise, virtually every VPIPing hand mixes call and raise:

You could fiddle around with these mixes of calls vs raises—doing a lot more calling or a lot more raising—and it would not affect your EV or exploitability nearly as much as it would in a heads-up pot. What you’re essentially doing by turning these dials is determining how the remaining EV is split between the players left to act (e.g., LJ and BB, and, to a lesser extent, SB).

It’s generally better for LJ when you raise, as this makes it much less likely the blinds will contest the pot and so more likely LJ will win it if you do not. Raising does not so much accrue EV for yourself as it does redistribute EV from BB → LJ.

Conversely, calling makes it more likely the blinds will enter the pot, allowing them to realize their equity at LJ’s expense. Sure, sometimes the blinds win a pot you would have won had you 3-bet, but calling has the advantage of risking less than raising would.

So for you, it often ends up being an even tradeoff, with most hands showing no clear preference for calling or raising. LJ loves it when you 3-bet because they benefit from the fold equity you are paying for, whereas BB loves it when you call because they get cheap overcalling opportunities you allowed for.

That’s what the equilibria look like, anyway. In a real-game situation, LJ might be a tough opponent and BB a soft one. In that case, you have a lot of incentive to call, as you don’t want to do your tough opponent any favors and you’d welcome weakness in the pot. Whereas if LJ is the soft player, you’d like to isolate weakness by 3-betting more aggressively to shut out tough opponents in the blinds.

Conclusion

Solver strategies are a product of a series of precisely balanced compromises between competing incentives. Every little detail matters, even if it is not obvious how. There is some reason why the solver calls K6s but not K7s. And there is some reason why it does so 20% of the time rather than 18%.

Some of these reasons are based on the opponent’s incentives on the current street, while others will pay off on specific runouts on future streets. Often, it’s both. Solvers are extremely efficient in this way.

However, you will never get all these balances exactly right in a real-game situation, and neither will your opponents. But by understanding all the tradeoffs, you can make better decisions about how to remain roughly balanced yourself. Plus, you will also be better equipped to predict imbalances in your opponents’ play and introduce intentional imbalances in your own game to exploit theirs.

Author

Andrew Brokos

Andrew Brokos has been a professional poker player, coach, and author for over 15 years. He co-hosts the Thinking Poker Podcast and is the author of the Play Optimal Poker books, among others.

Wizards, you don’t want to miss out on ‘Daily Dose of GTO,’ it’s the most valuable freeroll of the year!

We Are Hiring

We are looking for remarkable individuals to join us in our quest to build the next-generation poker training ecosystem. If you are passionate, dedicated, and driven to excel, we want to hear from you. Join us in redefining how poker is being studied.