Equity Realization

Equity and Expected Value

In poker jargon, equity expresses how much of the pot a hand will win, on average, at showdown against an opposing hand or range. The appeal of equity is that, unlike many poker metrics, it can be calculated simply and precisely. By understanding what share of the pot your hand would claim if there were no further betting, you can get a rough sense of what the hand is worth in a given situation.

“If there were no further betting” is an enormous caveat, however. Poker is all about betting! The more money in the effective stack and the more betting opportunities remaining, the less accurately equity represents the Expected Value of a hand, the amount it will actually win after all the betting is complete.

At one extreme, consider what happens when you are all in. You are guaranteed to see all five cards and the showdown, without the possibility of folding or making your opponent fold or putting any more money in the pot. Your equity tracks your EV exactly in this case, because there is no further betting.

At the other extreme, consider a pre-flop decision in a deep-stacked no-limit hold ‘em game. The amount of money remaining in the stacks is much greater than the size of the pot, and there will be three more betting streets before the showdown. Consequently, some hands with relatively good equity, such as A6o or K2o, have less EV than lower equity hands like 65s. Colloquially, we say 65s is more “playable”.

If you’re not sure what Equity or Expected value means, read these articles first:

Equity Realization

Equity realization (EQR) essentially measures playability. It tells us how well a hand will perform, relative to its equity, in a given situation. Equity realization is expressed as a percentage; Hands with greater than 100% EQR over-realize their equity, and hands with less than 100% EQR under-realize theirs.

Equity realization is a bridge between equity and expected value. Multiplying a hand’s equity times its EQR times the size of the pot yields its EV.

Equity × EQR × pot = EV

Over-Realizing Equity

There are two ways a hand can over-realize its equity:

- Put more money into a pot it is favored to win

This typically comes in the form of betting for value oneself but could also be the result of calling bluffs or mistaken “value bets” from weaker hands. - Cause an opponent to fold a hand with some chance of winning

Bluffing 🕶 is the most dramatic example of this, but even very strong hands over-realize equity as a result of folds.

A Simple Example

You hold AA before the flop against a single opponent who, unbeknownst to you, holds 72o. There is $100 in the pot. Your equity is about 88% of the pot, or $88. If you go all in for another $100 and your opponent folds, you win the entire pot of $100, which is 114% of your equity.

If your opponent calls, that is better yet. You still have just 88% equity, but there is now $300 in the pot, so that 88% is worth $264. Subtracting the $100 you wagered, you win an average of $164, or 186% of what your equity was worth before you bet.

Either way, you over-realize your equity. This is one of the many great things about strong hands: not only do they have a lot of equity, but they can over-realize that equity by betting to make the pot larger and/or deny equity to opponents.

Bluffing

It’s a bit counter-intuitive, but very weak hands also tend to over-realize their equity. That doesn’t make them “good”; it simply reflects that when you have very little equity, it doesn’t take much to outperform it. River bluffs, for instance, tend to have low EV at equilibrium. A savvy opponent will not fold at a frequency that makes bluffing very profitable. However, the hands you bluff with typically have little or no chance of winning at showdown, so even a small amount of EV from bluffing is better than their near-zero equity at showdown.

Under-Realizing Equity

The hands that under-realize equity most dramatically are in fact medium-strength hands, those that have a fair chance of winning at showdown but are not strong enough to bet for value. This makes sense when you remember that equity realization measures playability, how much a hand benefits or suffers from future betting opportunities. Strong hands benefit from making the pot larger. Weak hands benefit from bluffing. It’s the hands in the middle that suffer from betting, because they risk either putting more money in against better hands or folding to inferior ones.

Those are the two ways to under-realize equity:

- Putting more money into a pot you are not favored to win 🎰 📈

Even if the pot odds make a call correct, you’d still prefer not to put the money in if there were a way you could get to showdown without doing so. - Folding when you have a chance of winning at showdown

The greater your chance of winning, the more your hand suffers from folding its equity. Folding a hand with one out on the river doesn’t cost you much, as you probably weren’t going to win anyway. Folding the best hand to a river bluff is an expensive mistake that costs you the entire pot!

Estimating Equity Realization

Equity realization does not measure a hand’s absolute value. Remember: very weak hands often over-realize equity, but they still have low EV. However, by combining EQR with a rough estimate of your equity, you can get a better sense of what your hand is actually worth and whether you should continue investing in it.

Equity realization is always contextual. It depends on factors like position, board texture, stack sizes, and the composition of each player’s range. We cannot draw a conclusion like, “A9o has poor equity realization” in a vacuum any more than we can conclude, “A9o is a bad hand.” Solvers can tell us the exact EQR if both players play an equilibrium strategy on future streets, but in real poker games that rarely happens. Over the felt, you can only estimate a hand’s future equity realization. Some useful rules of thumb:

- All hands have lower EQR when playing out of position.

- Hands that anticipate value betting or bluffing profitably on later streets have higher EQR. This includes both hands that are already good candidates for betting and those with potential to improve to a hand strong enough to value bet or to hold an important blocker that will make bluffing profitable.

- Conversely, draws to medium-strength hands will under-realize equity just as medium-strength made hands do, because they will face the same dilemmas even if they are fortunate enough to improve.

- EQR depends on how well you and your opponents play later streets. If you miss value betting or bluffing opportunities, you will not realize as much equity as a solver would predict. If your opponents miss such opportunities, or if they pay off too light to your value bets or fold too often to your bluffs, you may realize more equity than a solver would predict.

- When your range consists mostly of weak hands, the rare strong hands realize more equity. Likewise, when your range consists mostly of strong hands, the few weak hands realize more equity.

- Stronger ranges realize more equity because they generate more fold equity. Weaker ranges realize less equity because they are frequently pushed out of the pot.

Equity Realization Out of Position

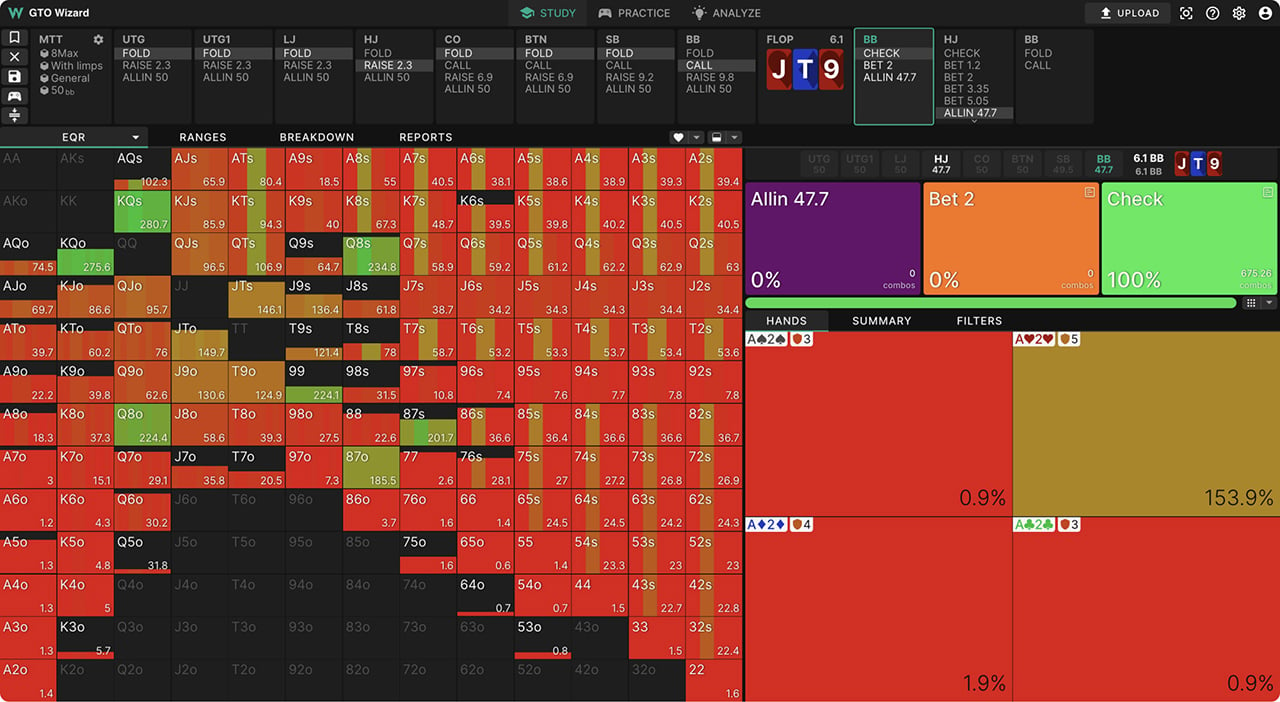

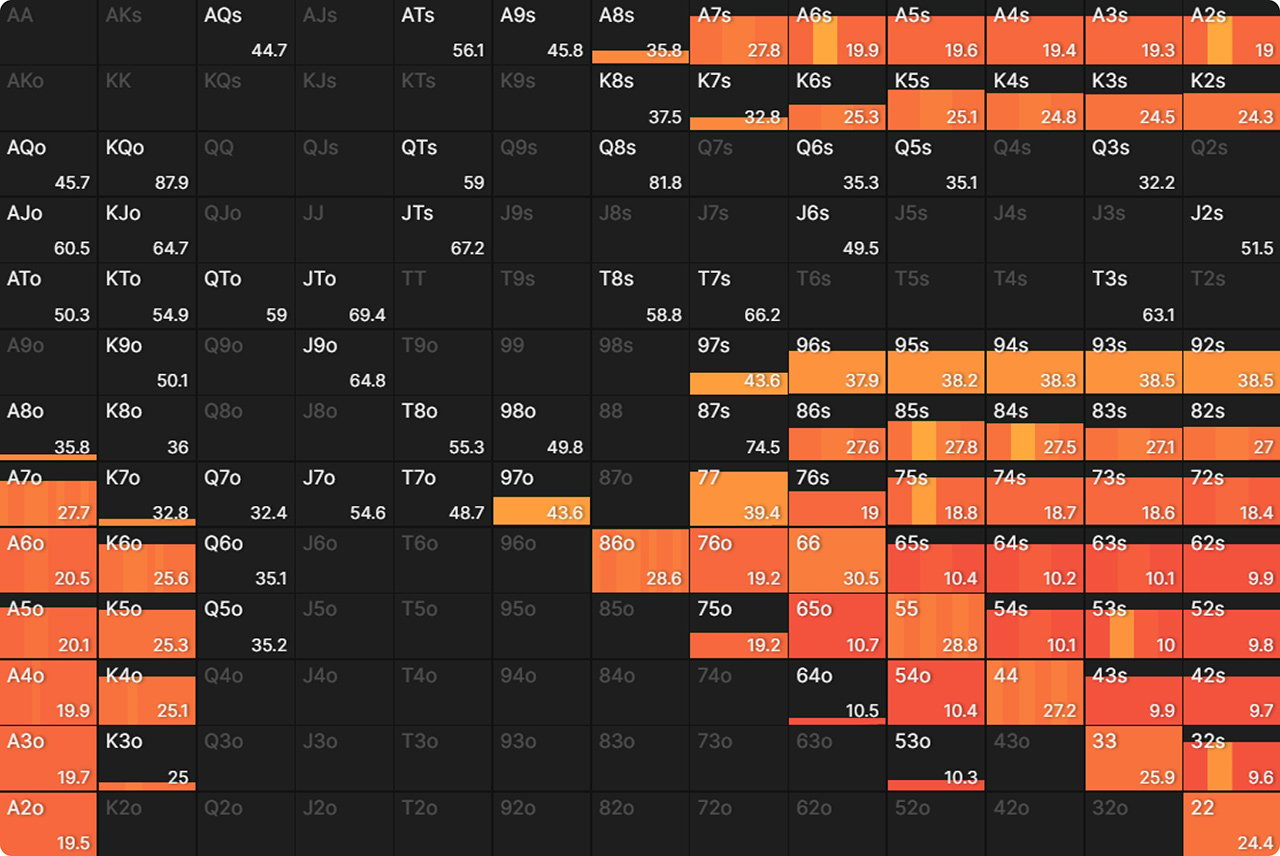

The following image shows the equity realization of each hand in the BB’s range when playing an MTT 50BB deep in a heads up pot against a HJ raiser on a J♥ T♦ 9♥ flop. Notice that most of these hands under-realize their equity, which is consistent with Rule #1 above. Look at the hands that do have >100% EQR and try to identify for yourself why each of them over-realizes its equity. Answers are below the image.

Mostly, these are the strongest hands in BB’s range: straights, sets, and two pairs. This is true even for bottom two pair and the low end of the straight. Because the BB’s range is wide and mostly weak, their few strong hands all overperform, even when they are not the literal nuts. Weak ranges expect to face more aggression, so the few strong hands in there get paid more.

Most ♥ draws over-realize equity, but the very weakest do not. 3♥ 2♥ realizes just 87% equity. This is because weaker draws are more likely to get bet off their equity before the river, and even when they do come in, they risk running into higher flushes. To be clear, 3♥ 2♥ still over-realizes its equity when it makes a flush. But the reward is lower than it would be with better draws and so does not fully compensate for all the other scenarios where this hand under-realizes its equity.

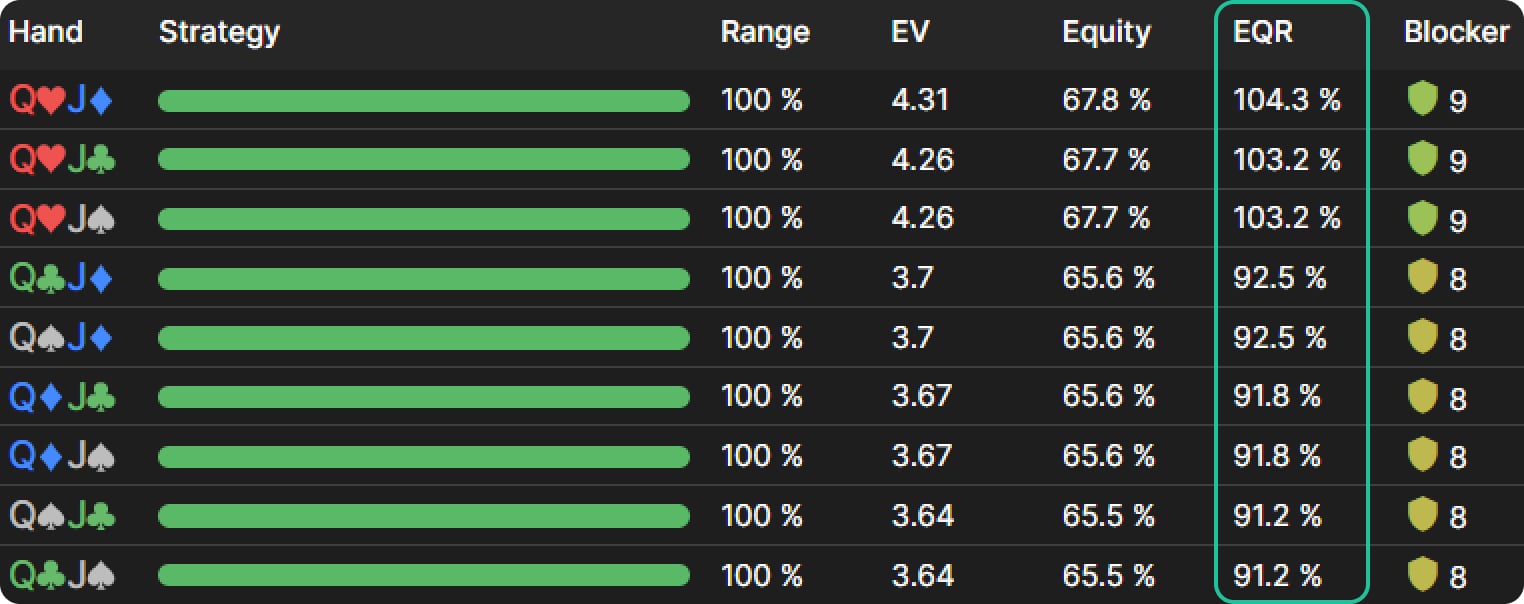

A straight draw by itself is not enough to over-realize equity on this board. It’s hard to get paid off when four straight cards are on the board, especially if the flush also comes in. QJ has >100% EQR only when holding the Q♥, and even then it barely clears the bar. Keep in mind, however, that QJ has a lot of raw equity–roughly 66%–so to say it underperforms its equity is not to say it is a bad hand.

Draws to lower straights do much worse. A pair plus an open-ended draw is usually a robust hand, but 98s realizes less than 25% of its equity. Bottom pair is not by itself very strong on this board, and drawing to the low end of a four-card straight is not particularly valuable either. This hand lacks the nut potential required to leverage implied odds. A backdoor flush draw is a big help, pulling the EQR up to nearly 50%. This is not only because of the potential to get value from a flush draw but also because 9♦ 8♦ will sometimes get to semi-bluff or take another card off on a ♦ turn in a scenario where a different 98 combo would get forced off its equity.

Equity Realization In Position

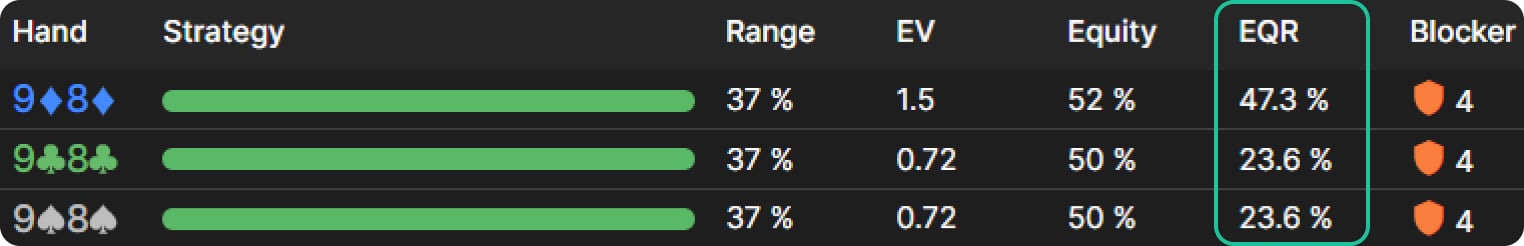

The HJ, with the benefit of position, realizes equity much more effectively than the BB.

Here is how their hands perform in the same scenario:

Notice that HJ’s EQR is higher across the board. Any two cards, in the hands of the in position player (who also benefits from having a stronger range and thus more fold equity), perform better than they would in the hands of their out of position opponent. HJ’s A♦ 2♦ realizes almost 100% of its equity, for instance, while the BB’s realizes less than 2%. This is because the HJ’s stronger range enables them to bluff profitably even with very weak hands, while the BB almost always ends up folding the same hands to a flop bet.

Using Equity Realization

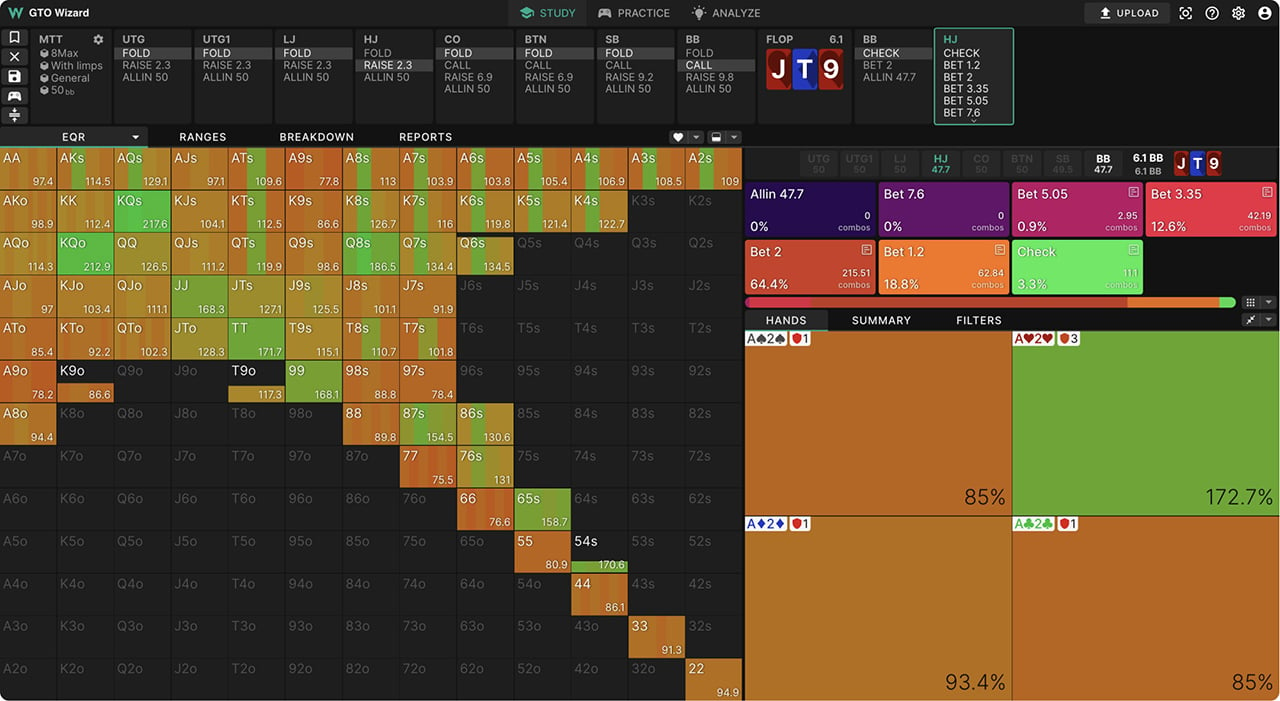

You can use your understanding of equity realization, combined with an estimate of a hand’s equity, to make better decisions about whether to continue to a bet or voluntarily grow the pot yourself. For example, here is the BB’s folding range when faced with a 33% pot continuation bet on this J♥ T♦ 9♥ flop:

A 33% pot bet lays odds of 4:1, yet many of these hands fold more than 20% equity.

Why? 🤔

Because they expect to under-realize that equity, and quite dramatically in some cases–97o folds despite having ~44% equity! Bad pairs, draws to bad straights, and even some Ace-high could call if this bet were all in and they were guaranteed to realize their equity. They must forfeit that equity on the flop because they will play poorly on future streets and often get pushed off their equity before showdown.

Conclusion

Equity realization is a bridge between equity and expected value. When making decisions over the felt, you will not know these values precisely. Estimating your equity and then adjusting, based on the guidelines in this article, for whether you expect to under- or over-realize that equity will help you make more accurate decisions than thinking in terms of equity alone. It will also encourage you to plan ahead by considering what actions your hand will take on various runouts.

Author

Andrew Brokos

Andrew Brokos has been a professional poker player, coach, and author for over 15 years. He co-hosts the Thinking Poker Podcast and is the author of the Play Optimal Poker books, among others.