ICM Survival Guide: How To Play OOP vs. a Covering Stack at the Final Table

Contesting a pot against a player who covers you at a final table (FT) is one of the most stressful situations in poker. The stakes are high, and the worst-case scenarios are frighteningly plausible, considering how bad they are. Your treasonous brain may flash memories of every time you’ve been coolered or sucked out on, providing an unwelcome reminder that you may be about to experience the same at one of the most important moments of your career.

That anxiety is only heightened when you are out of position (OOP). Acting first puts you even more at the mercy of your opponent, forcing you to navigate a series of uncomfortable tradeoffs between the desire to secure your equity in the pot and the need to conserve the last of your chips.

To some extent, this is simply the nature of tournament poker. When you make the FT of a large-field tournament, a single mistake or bad beat could cost you many times your average buy-in, so much so that the results of your entire year may be largely determined by two or three big pots at final tables.

The results of your entire year may be largely determined by two or three big pots at final tables.

With the stakes so high, it is crucial to understand how to navigate these tricky situations. It may not alleviate your anxiety entirely, but in my experience, these scenarios are most stressful when you are unprepared for them. During moments of heightened anxiety, you may find it difficult to access the rational part of your brain upon which you typically rely to help you navigate unfamiliar situations. Thus, it pays to have a strong understanding of the fundamentals to help you steer clear of the biggest mistakes.

In this article, we will investigate postflop play at the final table when OOP to a covering opponent in a single-raised pot (SRP).

The Scenario

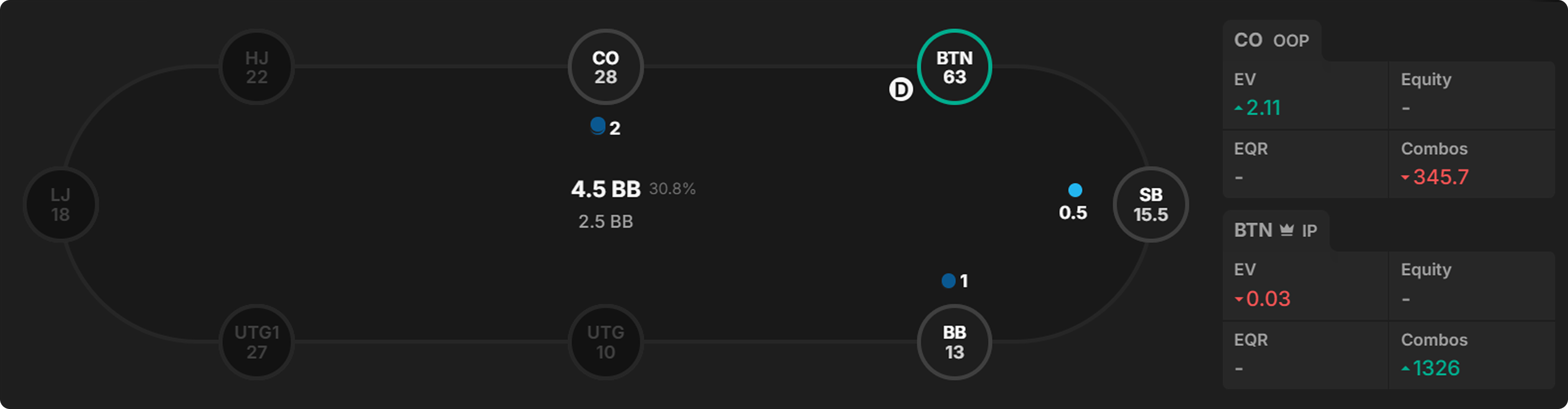

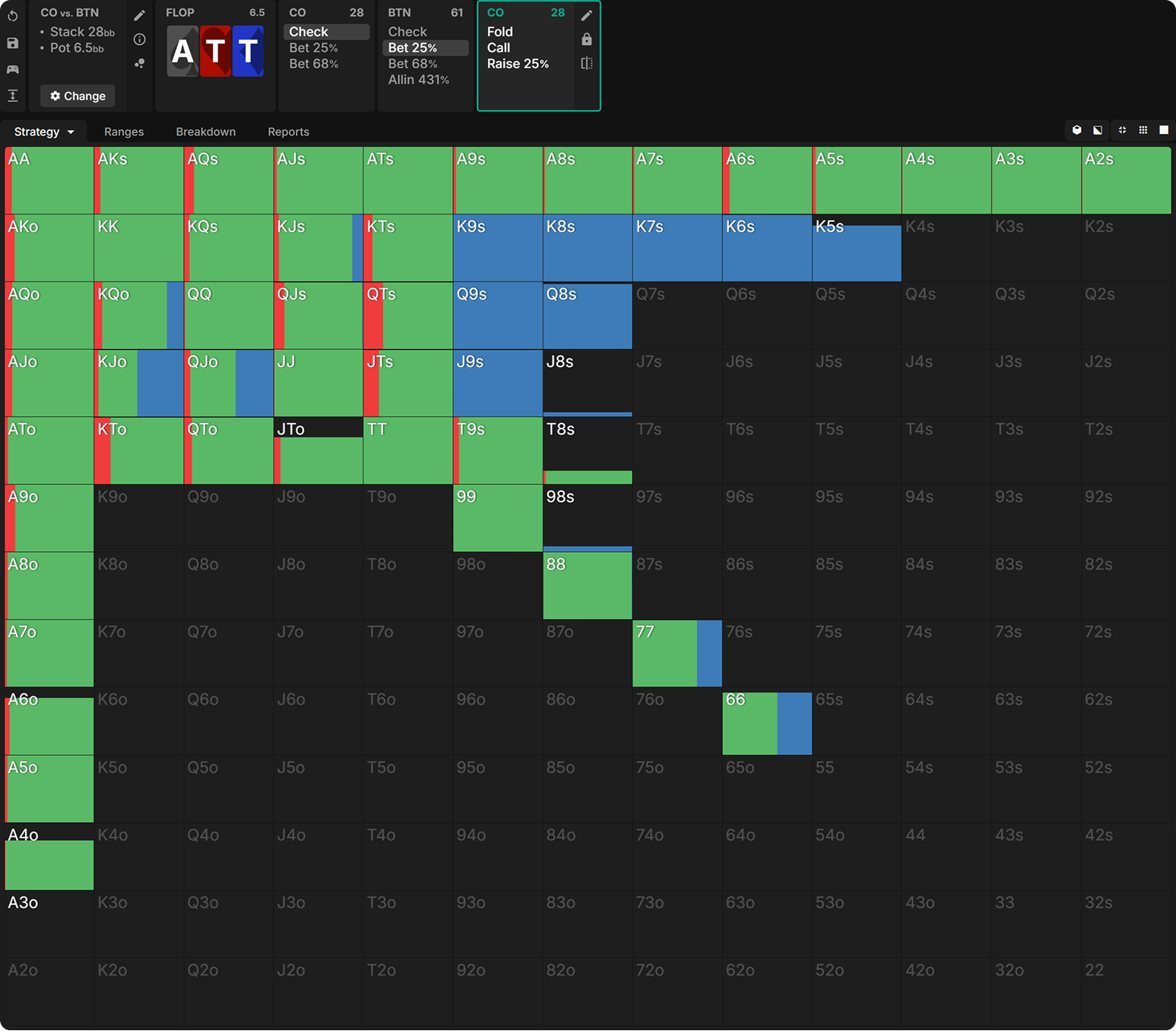

The examples we investigate will come from an 8-handed FT with an average stack of 25bb. The CO min-opens off a 30bb stack and is called by the BTN, who, with 63bb, enjoys a big lead over the rest of the table.

All positions with their stacks are also shown in the chart below:

The principles we derive from these examples will apply to other scenarios where you are OOP against a covering stack, but it’s important to note that this is an especially dramatic scenario. The CO here faces an enormous risk premium of 18.1%, which is a function of having more chips than so many of the remaining players. If the Hero’s stack were shorter or if fewer players remained, the risk premium would not be so high. The same considerations would apply to postflop play, but they would not apply as dramatically.

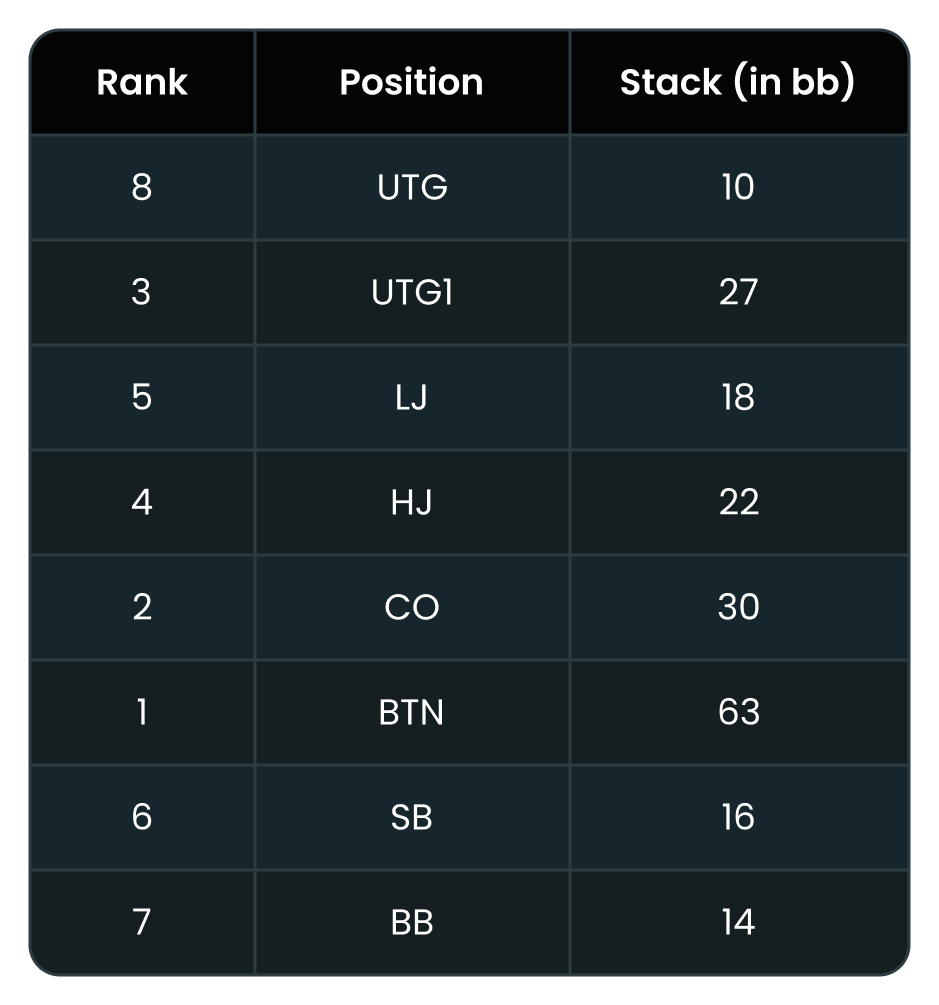

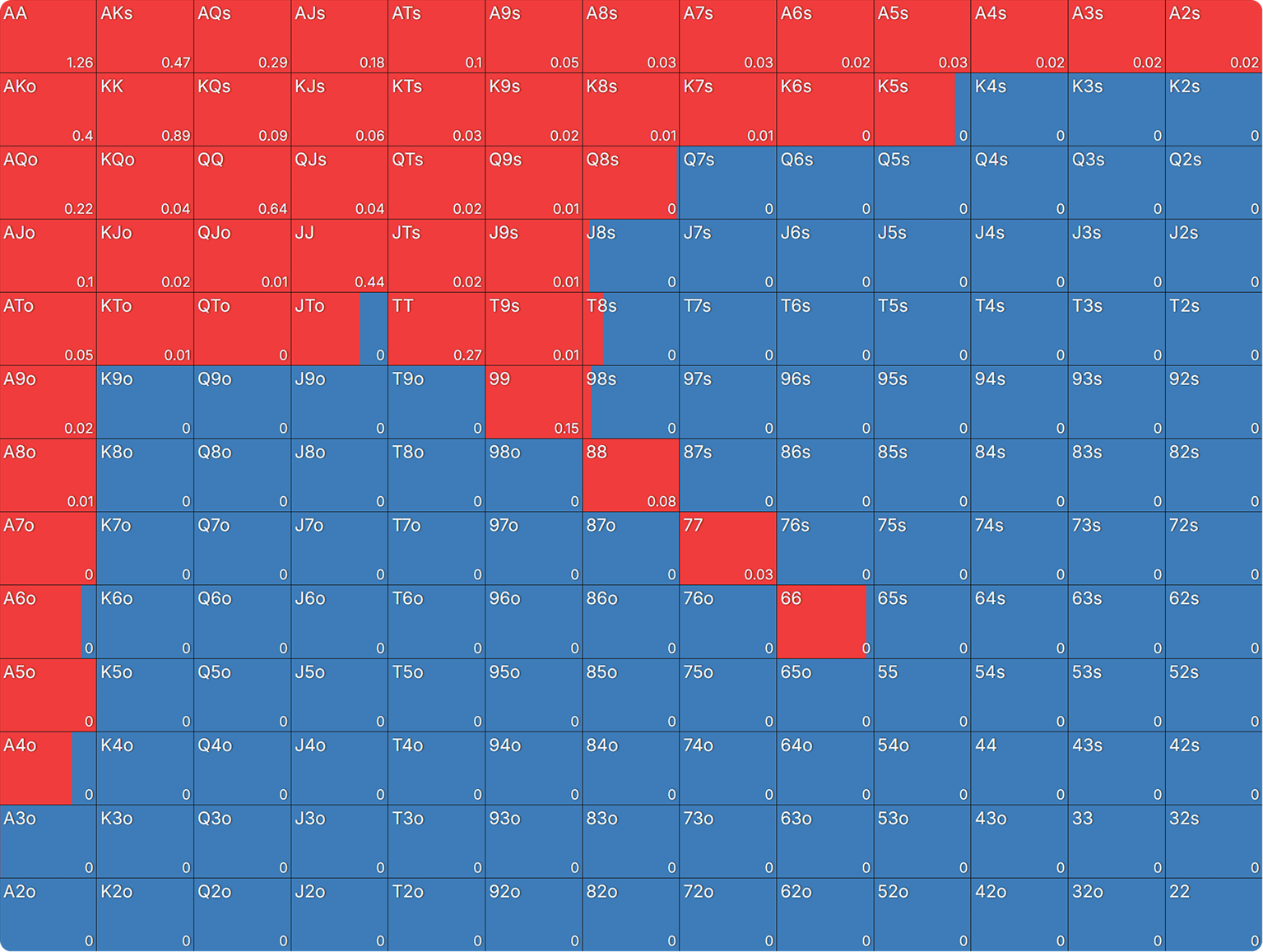

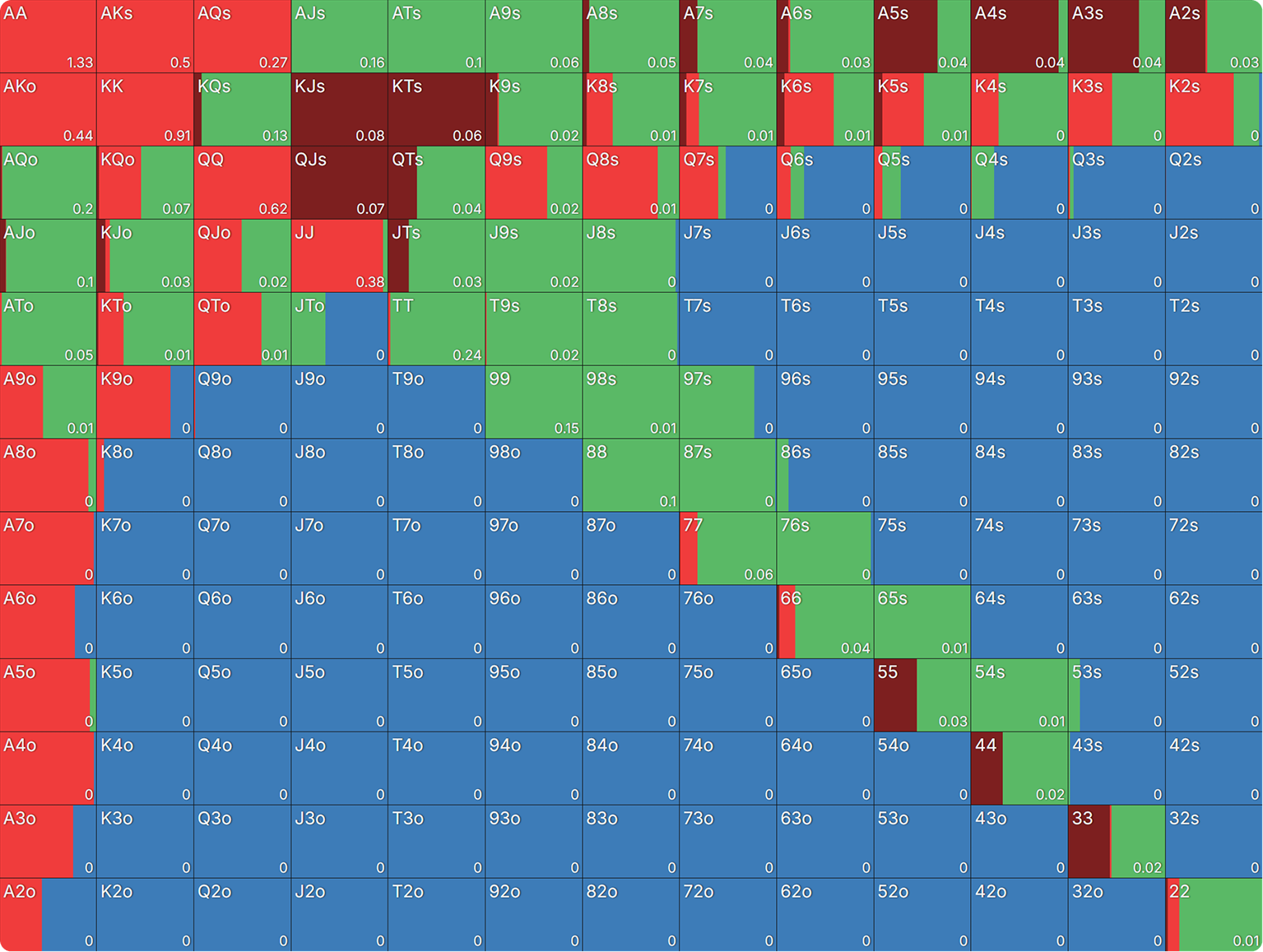

The CO in this scenario opens 26.1% of hands, with an emphasis on Ace-x and King-x. High card blockers are always important when raising under ICM pressure, but they are especially valuable with a covering stack behind you. As we will see, getting action from the big stack on the BTN will be very bad for CO!

For comparison’s sake, a CO with a slightly above average stack of 27bb opens 30.5% of hands when they cover the BTN:

So, the risk of getting called or 3-bet by the covering stack on the BTN ought to be baked into CO’s opening strategy.

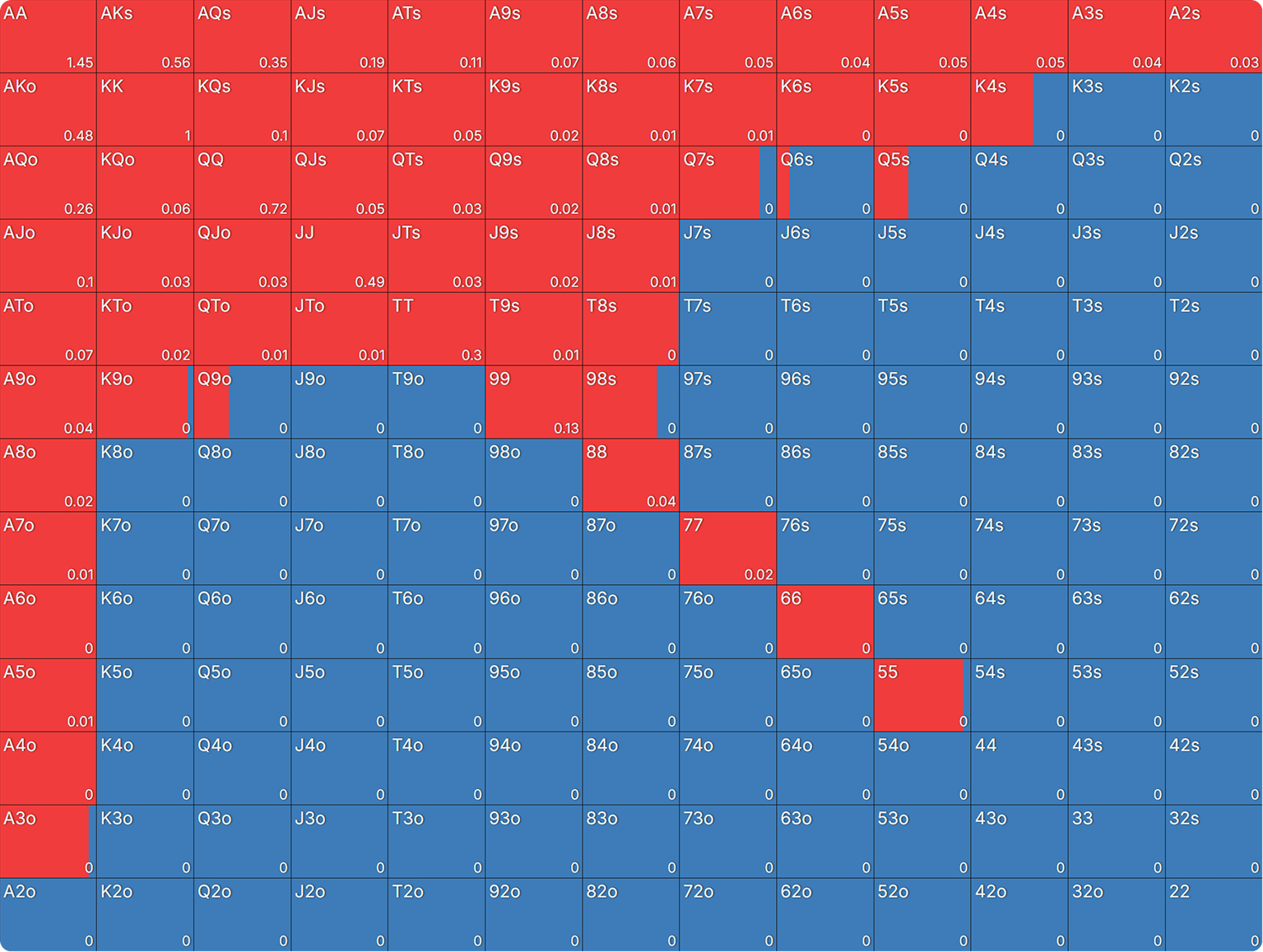

Flatting is an important part of BTN’s response to this open. They call more than they 3-bet! Their calling range is strong but capped, with an emphasis on Broadway cards, pocket pairs, suited Ace-x (and, to a lesser extent, King-x), and suited connectors. They call with some rather weak suited connectors, which is a clue that they will over-realize equity when playing postflop, thanks to their position and the CO’s risk premium.

The Flops

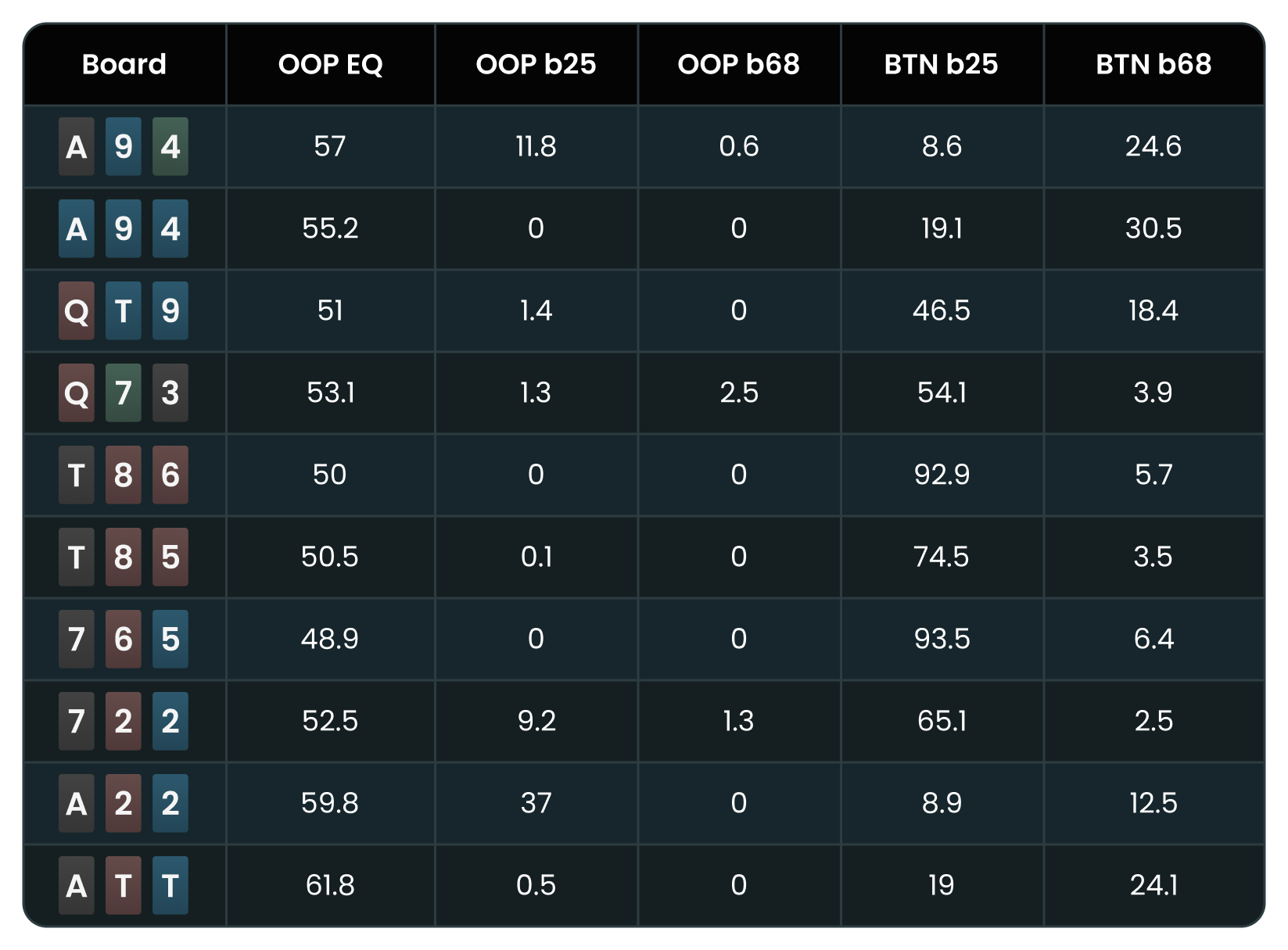

We cannot run reports on ICM simulations, but we can investigate a variety of flop textures to get a sense of the incentives and underlying range dynamics on each of them. What patterns do you notice?

The first thing that jumps out at me is that it is almost always a mistake for CO to bet. In the rare instances where they do bet, they bet small.

This makes sense, given CO’s strong incentive not to play a big pot against BTN. With a risk premium of ~18%, CO will have to check and fold many marginal hands, and very few hands are so strong that they want to put money in the pot.

CO’s primary concern must be with protecting the tournament equity in their stack rather than with protecting their equity in the pot or growing a pot they are favored to win.

Thus, they almost always prefer checking and calling to betting and raising, even when they have a hand that is too strong to fold.

Another trend is that Ace-high flops are noticeably better for CO than other flops. This makes sense, as we have already noted that CO’s opening range is heavy on Ace-x and King-x. There are none shown here, but King-high flops tend to be somewhat good for CO as well, though not as markedly so. This is partly because CO opens less King-x but also because BTN flats more of it, whereas BTN has a lot of incentive to raise when they have an Ace blocker.

Disconnected and rainbow boards are also good for CO. This is partly because BTN has more suited and connected hands in their flatting range but also because more dynamic boards generally favor the in position (IP) player. Dynamic boards make it dangerous to grow the pot from OOP because even when your hand is strong on the current street, you can’t be sure it will remain strong on later streets.

When Should I Bet?

Wrong question!

OK, not wrong exactly, but it’s too soon to focus on that. When you see a pattern like, “CO almost always checks, except in a couple of rare cases,” it’s tempting to immediately look into those rare cases. But that violates an important principle of poker study:

Learn the rule before you learn the exception.

Your takeaway from the chart with the flop samples should be that, when a covering stack flats you IP and your risk premium is high, you should almost certainly start with a check on the flop. Even if you blindly followed that rule without exception, you’d rarely make a mistake.

Theoretically, you could do a bit better by finding those rare exceptions. The risk is that, because the base rate for betting is so low, there is a lot more room to make mistakes by betting when you shouldn’t than by checking when you shouldn’t.

When in doubt, check. When not in doubt, probably still check. Only bet if you are deeply familiar with the rule and the reasons behind it and are confident those reasons do not apply in the spot you are faced with. Even then, you should think twice about whether you’re really sure this is an exception.

Why So Much Checking?

That’s a better question to start with. We’ve said already that this is a function of CO’s risk premium and positional disadvantage, which combine to make growing the pot an unappealing prospect with all but their strongest hands (and sometimes not even then).

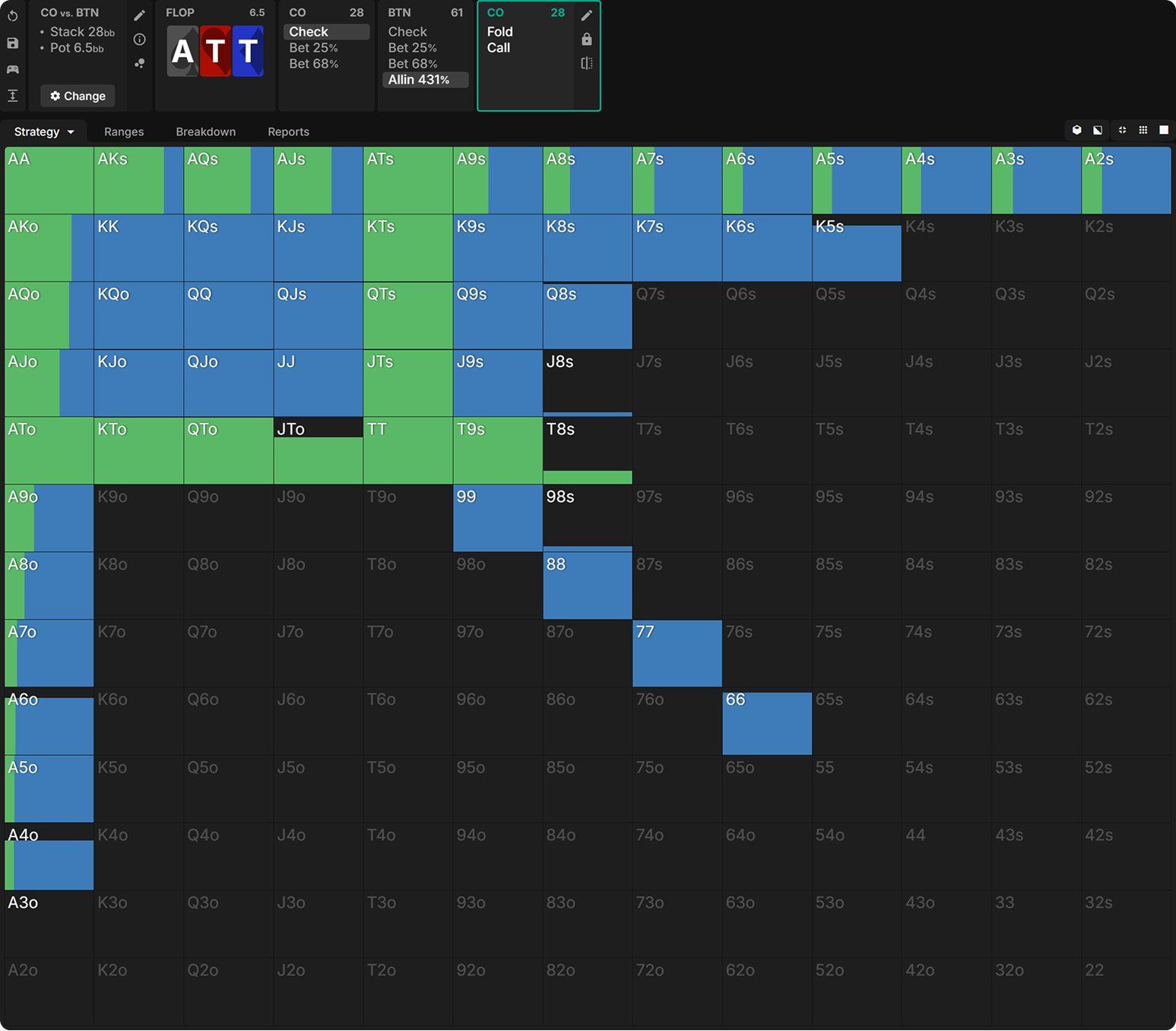

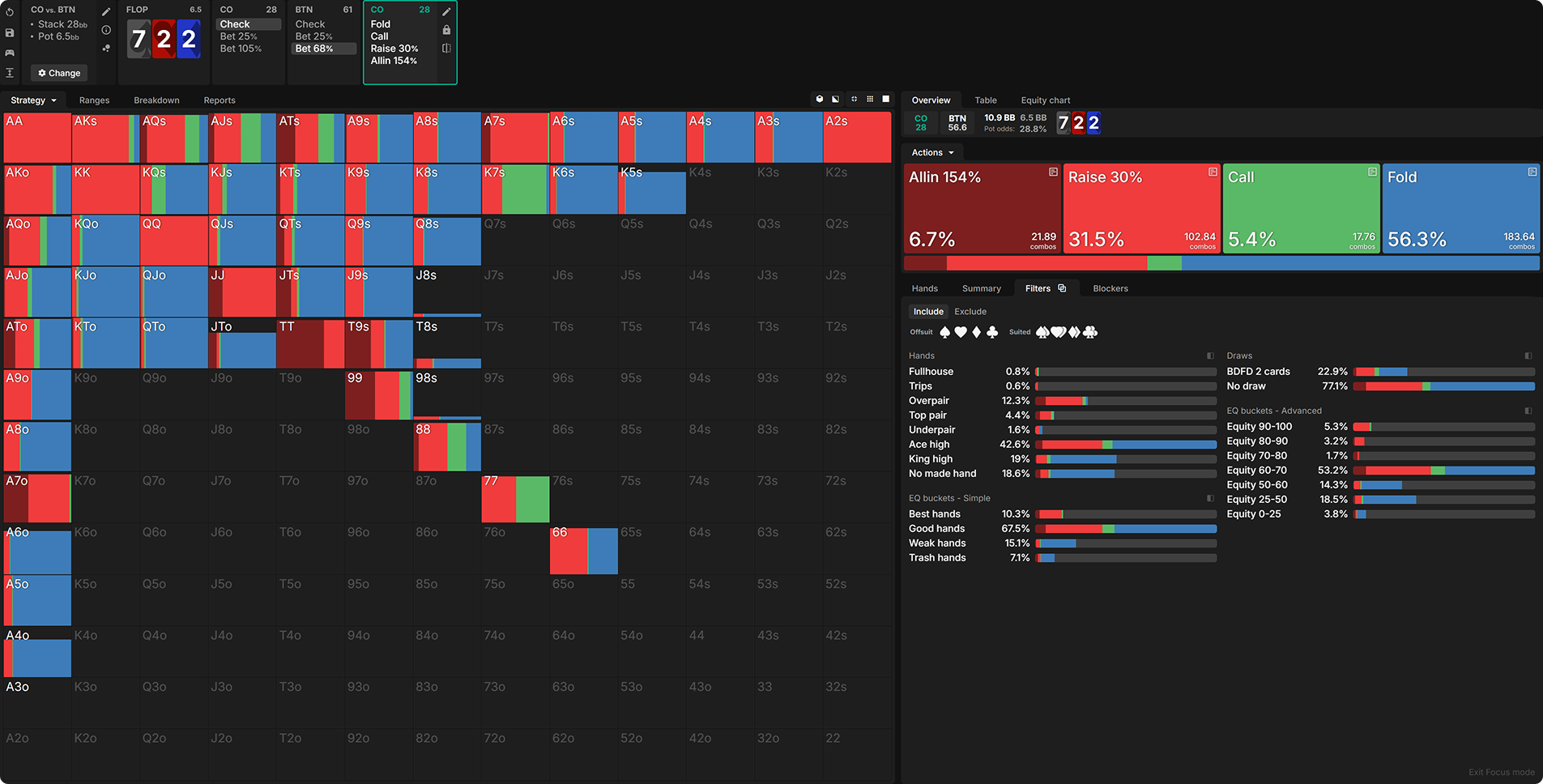

To ensure we understand what’s going on here, let’s look at the most counterintuitive case: the A♠T♥T♦ flop. Despite flopping more than 60% of the equity, CO basically never bets.

To see why, let’s look at CO’s response to a 4x pot shove from BTN. Even though this is not a play BTN ever makes at equilibrium, the solver’s unexploitable response provides a sense of which hands in CO’s range are strong enough to stack off.

CO is indifferent to folding AK, which suggests that it is profitable to stack off only with trips or better. In addition to being a small part of CO’s range, trips block BTN from having the hands with which they would be excited to stack off. With only two Tens remaining in the deck, holding one of them cuts in half the likelihood of your opponent holding one, which means your bets get a lot of folds. Ordinarily, you are happy to get folds when playing with a high risk premium, but these hands are so strong that any hand BTN folds has virtually no chance of drawing out anyway.

Checking has the virtue of inducing bluffs, which Ten-x does not block. And because CO is checking so many hands that will eventually fold if BTN keeps the pressure up, there’s a lot of incentive for BTN to bluff.

Understanding BTN’s Strategy

Before we look at how CO responds to bets on various board textures, let’s take a moment to think about the big picture of how BTN plays when checked to. Broadly speaking, they play one of two strategies, depending on the flop:

- On boards where equities run close, they bet small at a high frequency. The more of a nuts advantage they have, the more betting they can do.

- On boards where CO flops a big equity advantage, BTN bets less frequently, often for a larger size.

(I can’t say for sure without running a report, but I don’t expect there will be boards where BTN flops a large equity advantage. Their preflop range is much weaker than CO’s, so even very favorable flops like T86 give them only a slight equity advantage.)

This isn’t all-or-nothing, as BTN uses both bet sizes on most boards, but that’s the general trend. The small bets come from a more linear range, targeting CO’s weak hands, of which they will have many on a flop like T86. On more dynamic flops, there is more value in folding out CO’s weak hands, as they will have a better chance of drawing out.

BTN’s larger bets are more polar, designed to pressure CO’s medium hands. Given CO’s risk premium, “medium” can mean hands as strong as top pair! They immediately fold some of their top pair to a 68% pot bet on ATT:

On more static, high card boards, CO has fewer weak hands, and those weak hands have less equity. So, there is less to gain from attacking them and more to risk in terms of running into strong hands.

Responding to a Bet on Static Flops

CO folds often after checking, more than MDF would advise (MDF is generally not a good guide to defending against a cold-caller, especially not when ICM considerations are in play). However, when they don’t fold, raising is an important part of their strategy on certain flops, which might be surprising in light of what we said above about not wanting to grow the pot.

But really, CO’s concern is not so much growing the pot as it is going to showdown in a large pot. The most reliable way to avoid that is to fold. The next most reliable way is to raise, which can both deny equity and eliminate the risk of playing OOP on later streets.

We’ll start by looking at CO’s response on more static flops, however, where raising is not so important.

We saw above that CO’s response to a large, polar bet on ATT involved no raising and even some folds from top pair. Top pair with a weak kicker may have good equity vs BTN’s betting range, but it won’t realize that equity well. Two more betting streets lay between CO and the showdown they crave, and a big pot is already brewing. Given the danger of getting stacked by BTN, getting out immediately when you know you won’t be able to stand a large pot is a perfectly reasonable thing to do.

Facing a smaller bet, CO never folds top pair. They even have a few raises, though no hand purely prefers raising:

CO has some raises because BTN’s small bet is more linear and includes more draws and top pair of their own. CO has some incentive to raise into these hands to prevent them from checking back the turn. As with betting the flop, however, you may well be better off playing a pure call strategy than looking for these rare exceptions.

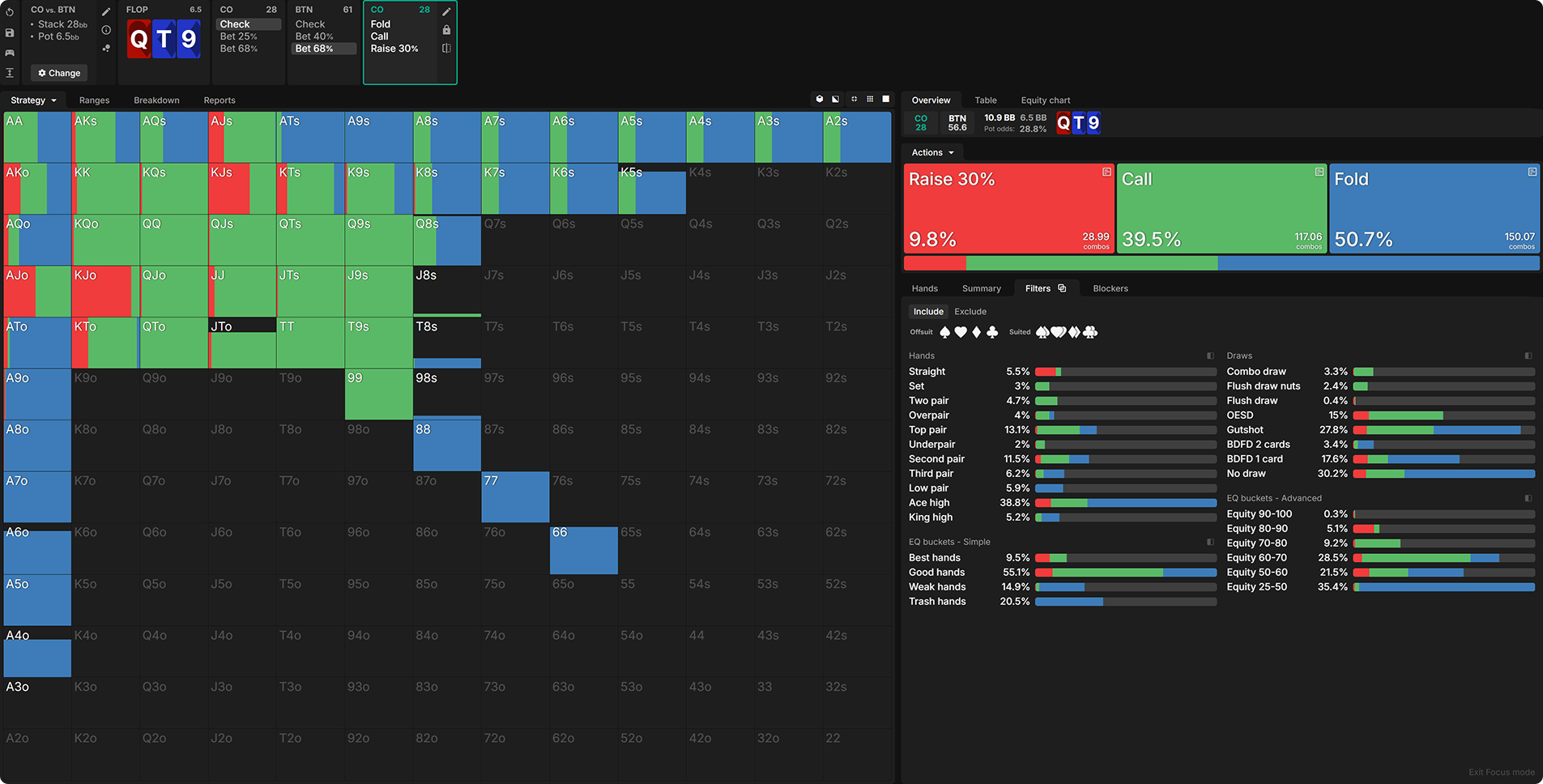

QJ9 is also a fairly static flop. The flopped nuts is tough to draw out on, and only two overcards can fall. So, CO’s response on this board looks similar, with a modest raising range built around their flopped straights:

Responding to a Bet on a Dynamic Flop

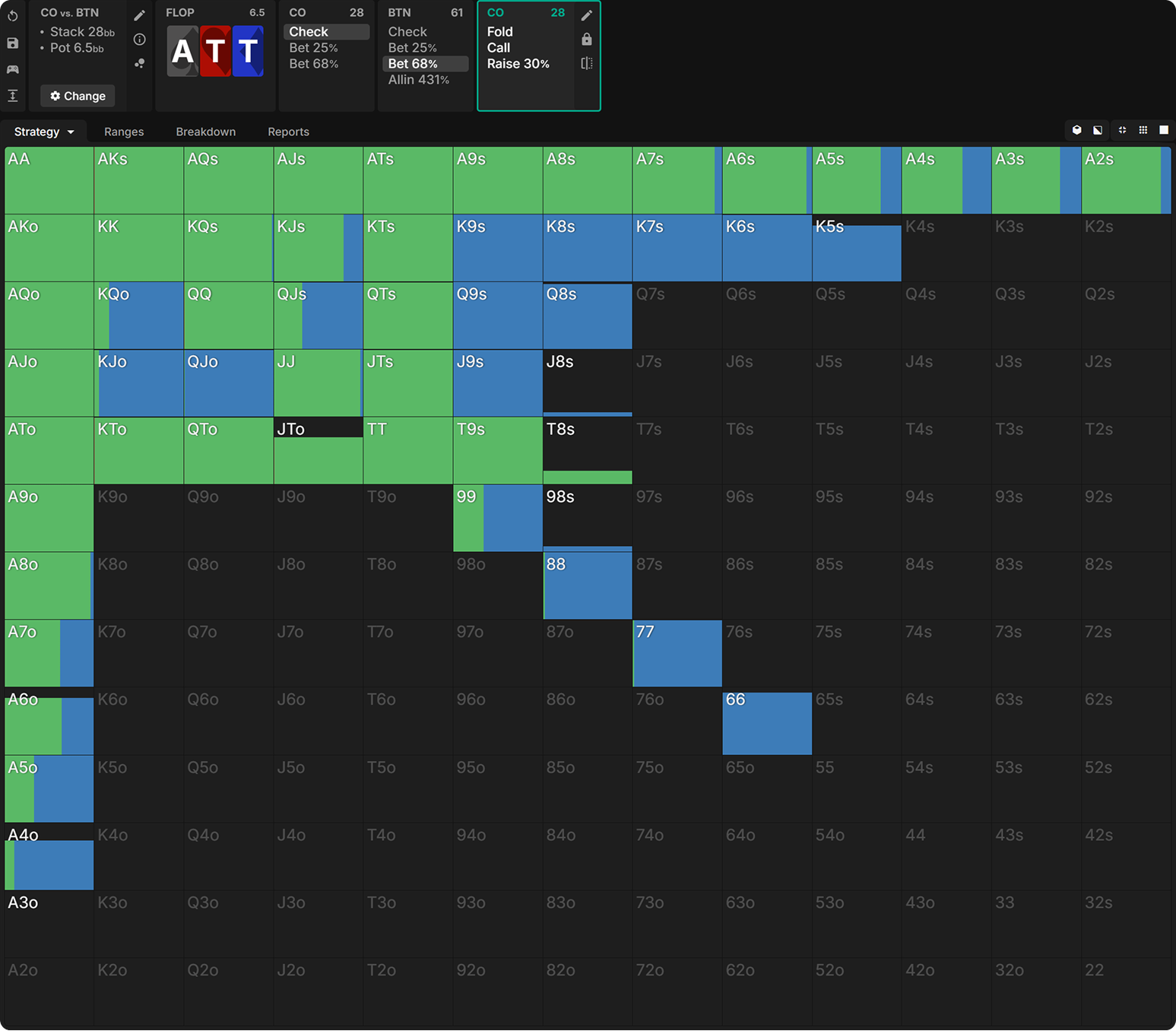

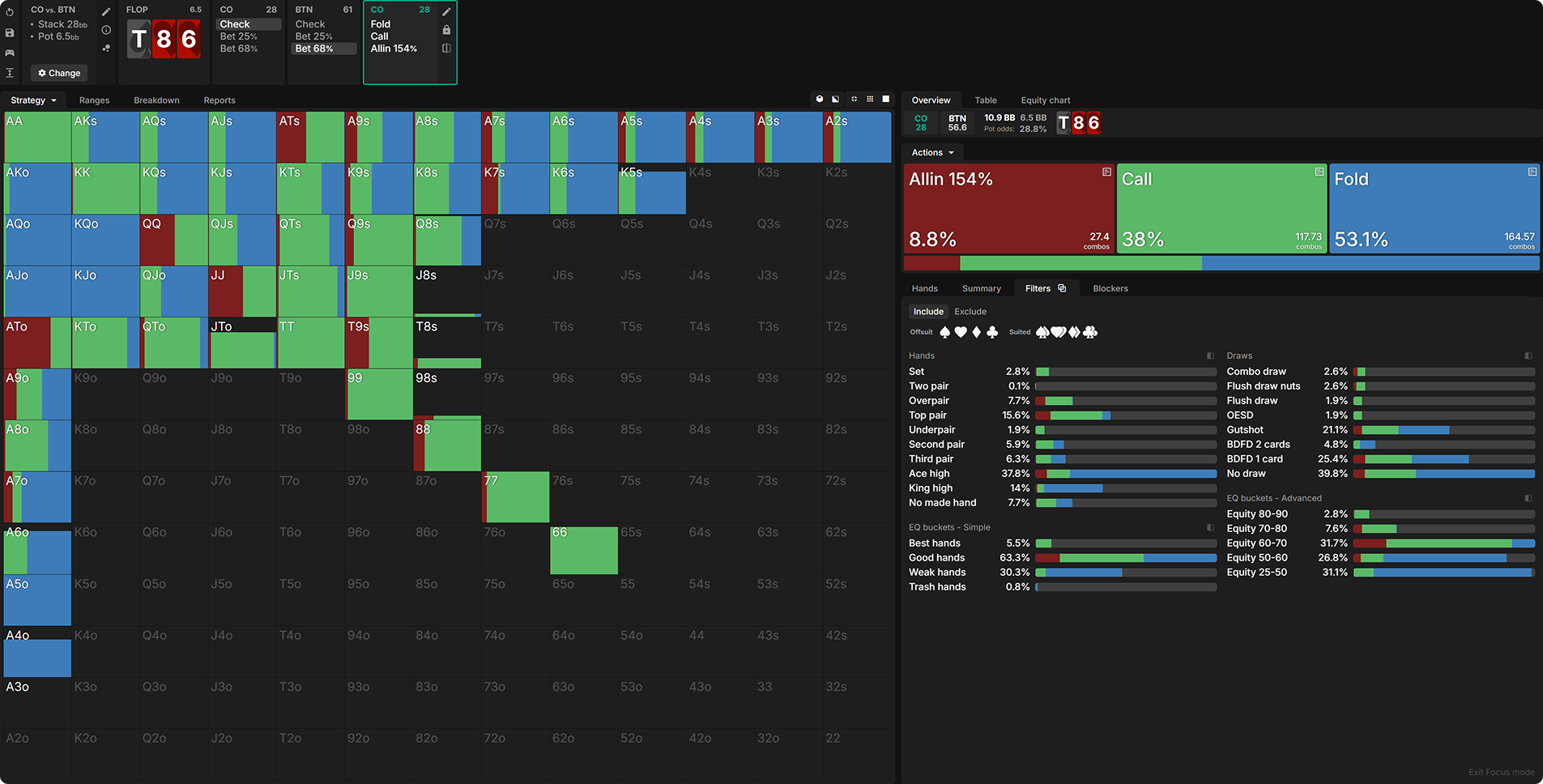

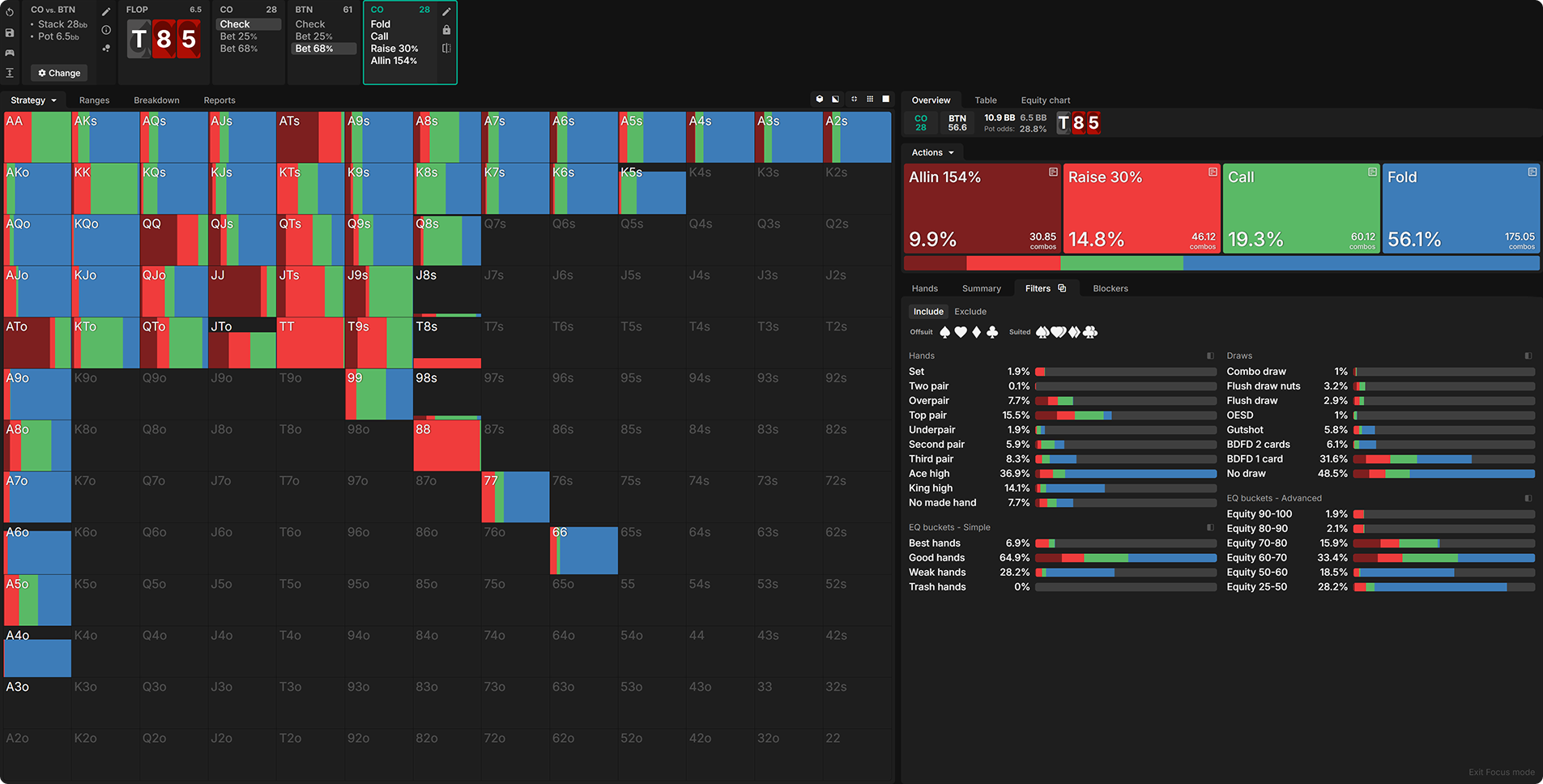

Dynamic flops change the risk calculus for raising. CO folds more often on T86 than on ATT, but when they don’t fold, they’re more interested in raising. Specifically, they are more interested in jamming, which both denies equity and eliminates the liability of playing OOP on future streets.

CO’s jams are not their strongest hands. Rather, they are strong but vulnerable, mostly AT, JJ, and QQ, plus some strong draws:

Changing the 6♥ to a 5♥ makes the board more dynamic, eliminating the risk of flopped straights and introducing more draws. This incentivizes CO to jam roughly the same hands but also to have some smaller raises with even stronger hands:

Despite the lack of straight and flush draws, 722r is also an extremely dynamic flop, as most turn cards will give both players some top pair while also reducing the value of hands that were already paired on the flop.

Facing a large bet on this flop, CO plays almost exclusively a raise-or-fold strategy. Their small calling range is well protected, with 77 being the hand that calls at the highest frequency!

Conclusion

When you open a pot, getting called by a player with position on you is usually one of the worst possible outcomes, second only to getting 3-bet. It’s an even worse outcome when that player covers you in a high risk premium spot, such as at a final table.

You should start mourning this pot before the flop is dealt.

Unless you get a lucky flop, you probably aren’t going to win it. Your top priority should be protecting your remaining chips, not fighting tooth and nail for the pot.

- If you flop nothing, you should generally check and give up.

- If you flop a marginal hand, you should still generally check. You can get a bit more stubborn, but ultimately, you’ll still need to give it up if you face heavy pressure.

- If you flop a monster strong enough to play for your stack despite the high risk premium, you should still generally start with a check. You will be checking so many other, weaker hands that your opponent will have a lot of incentive to bet regardless of their holding.

If they do bet, then you should seriously consider raising your strongest hands, as slow-playing is risky. In a different context, the risk might be worth it for the potential reward of winning a big(ger) pot, but the calculus changes at a final table. Securing a pot you’re currently winning is generally more important than getting more chips into that pot, even if you are a big favorite.

Final tables put a premium on avoiding risk, with tight and aggressive play being the safest strategy there is. Tight (checking and folding) keeps you out of trouble. Aggressive (raising when you aren’t going to fold) maximizes your chances of winning the pot should you deem it worth contesting. Only under the most favorable of circumstances should you consider doing otherwise.

Author

Andrew Brokos

Andrew Brokos has been a professional poker player, coach, and author for over 15 years. He co-hosts the Thinking Poker Podcast and is the author of the Play Optimal Poker books, among others.

Wizards, you don’t want to miss out on ‘Daily Dose of GTO,’ it’s the most valuable freeroll of the year!

We Are Hiring

We are looking for remarkable individuals to join us in our quest to build the next-generation poker training ecosystem. If you are passionate, dedicated, and driven to excel, we want to hear from you. Join us in redefining how poker is being studied.