Tournament Poker’s Hidden Stakes

In this era of game theory and solvers and poker games running at a huge variety of stakes at venues all around the world, as well as on dozens of apps and online poker sites, it’s easy to forget that, for the majority of its existence, poker has been a game of hustlers. In the saloons of the Wild West, the backrooms of Texas roadhouses, and even the casinos of 1970s Las Vegas, winning money at poker was not primarily about hand reading or bluffing frequencies or balancing ranges. The essential poker skill was convincing people who were not as good as you to wager large sums against you (and, perhaps, getting out of town afterward with your winnings and all your limbs).

This remains an important yet under-discussed skill in the modern times of poker. Perhaps it is no surprise that the people trying to sucker fish into bad wagers aren’t going out of their way to advertise what they are up to. Nevertheless, many of poker’s rules, formats, and innovations can be best understood in this context. That includes the innovation of tournament poker.

Why is a player who calls a large bet on the river not required to show their losing hand? So that people won’t feel sheepish about making bad calls. Why introduce twists on tried-and-true poker games such as bounties, bomb pots, the stand up game, or double and triple boards? They create excitement and variety, which many recreational players appreciate, but they also increase the edge of more skilled players, who will better recognize and adapt to the novel incentives these variations introduce.

Variations on familiar games create excitement, but they also increase the edge of skilled players, who are better at adapting to novel incentives these variations introduce.

Tournament poker began as just another fun twist on a familiar game. Like the examples above, it created variety and excitement along with complicated incentives that even now, with the assistance of powerful algorithms and computers, the best players in the world still struggle to make sense of. Tournament poker has become so wildly successful because it excels at those objectives:

- Creating a format that is fun and exciting for recreational players and

- Also financially rewarding for professionals

There’s nothing intrinsically nefarious about that. Something in it for everyone is the hallmark of a good innovation. But what many players don’t realize is that tournament poker is also a clever means of tricking people into playing for much higher stakes than they otherwise would. The trick is so elusive that even many tournament professionals don’t realize it and make some mistakes as a result.

Tournament poker is a clever means of tricking people into playing for much higher stakes than they otherwise would.

To avoid inadvertently playing at stakes higher (or lower) than you would prefer, it is essential to understand what a poker tournament is at the most fundamental level. Only then can you make optimal decisions about game selection and about your strategy at the table.

Tournament Poker’s One Weird Trick

When you sit in a cash game, it’s easy to understand what’s at stake. You can count how much money you have on the table, how much is in the pot, and how much you are wagering on any particular decision. If you ever get tired of playing or uncomfortable with the stakes, you can cash out and leave.

The trick of tournament poker is that it appears to offer the same transparency. In fact, many people will tell you they prefer tournament poker because of its limited downside: when you buy in for $500, that’s the final price, that’s all you can lose. You don’t need to keep rebuying to keep playing.

This argument has never really made sense to me. Most poker tournaments now feature rebuys, offering exactly the same opportunity as a cash game to pony up more money and keep playing if you lose your initial investment. No one forces you to keep rebuying in a cash game, either. If you buy into a cash game for $500, that’s all you can lose unless you choose to rebuy. If you win a big pot and find yourself with more money on the table than you’re comfortable with, you can cash out and leave (the prohibition against “ratholing”—taking some of your winnings off the table and continuing to play—is yet another of those rules designed to persuade players to play for larger sums than they’d prefer).

In tournament poker, you can’t just cash out and leave. In fact, the entire goal of tournament poker is to keep increasing the value of your stack so that it is eventually worth many times your initial investment. If they are lucky, a player who bought in for $500 may find themselves with $10,000 worth of chips in front of them. In all likelihood, they will lose most of that $10,000 because that’s how poker tournaments go. But because the chips don’t have dollar signs on them and can’t be straightforwardly converted to cash, it doesn’t feel like that much is at stake.

The entire goal of tournament poker is to keep increasing the value of your stack so that it is worth many times your initial investment. In all likelihood, you will eventually lose most of those winnings.

What many people don’t understand about tournament poker is that, when you enter, you are committing to the possibility of playing for and probably losing many times the amount you buy in for. That is the best-case scenario, short of winning the entire tournament. Even when you cash for several times your buy-in, it is likely that your stack was at some point worth much more than the amount you cashed for.

Had you been playing a cash game, you could and probably would have cashed out those winnings and gone home happy. But because tournament poker prohibits you from doing so, you continued to wager greater and greater sums until you eventually lost most of what you’d won. And because skilled players are disproportionately likely to go deep in poker tournaments, you wagered those enormous sums against a much tougher average opponent than those you faced in the early rounds of the tournament, when you were actually wagering the amount you bought in for.

The prize for winning a pot at most stages of a poker tournament is the opportunity and obligation to play for higher stakes against tougher competition.

In a cash game, the prize for winning a pot is chips that can be cashed out at any time. The prize for winning a pot at most stages of a poker tournament is the opportunity and obligation to play for higher stakes against tougher competition. And the prize for winning at those higher stakes is the obligation to play at still higher stakes against even tougher competition. A type of leverage that you cannot opt out of.

The Poker Machine

A poker tournament, like any form of poker, is a machine that takes as its inputs time, cash, and poker skill. These poker machines output cash and the experience of playing poker.

A poker tournament is a machine that takes as its inputs time, money, and poker skill and outputs money and the experience of playing poker.

The distinction between a professional and a recreational player is, at a literal level, about which of these outputs is the primary motivation for playing. Of course, most recreational players want to win money, but it is not their primary motivation. They want the experience of playing poker, and they are willing to pay for it. While professionals still care to some degree about the quality of their experience while playing, they are primarily in it for the money, just like any other career.

My intention is not to insist that one format is better than another. Rather, it is to help you better understand what exactly each has to offer, so that you can make decisions about what and when to play that will better align with your objectives.

Part of the appeal of poker tournaments—and part of their deceptiveness—is that the largest possible outputs are very large indeed, much more than you could expect to win by buying in for an equivalent amount in a cash game. This is precisely because players cannot take their winnings off the table and are forced to keep wagering them. Occasionally, you will be the ultimate victor who benefits from that, and that’s a great experience, but it’s important to understand that, most of the time, you will be one of the many compelled to wager sums that you’d really prefer to cash out, if you could.

Even professionals get duped by the very large prizes and overestimate the value of the time they invest in a given poker tournament. They fail to ask whether the same inputs of time, money, and poker skill wouldn’t yield a greater output of money if invested in a different game.

The Fundamental Unit of Poker Profit

To be fair, cash games are a bit deceptive themselves. They give the impression that money is won or lost based on the result of a hand of poker, but what we call a “hand” is in fact just a bundle of individual decisions. Successful players understand that the focus of strategy should not be on winning hands but rather on selecting the highest EV option at each decision point. This is true even though your payoffs are not based on the outcome of each individual decision but on the combined result of several individual decisions.

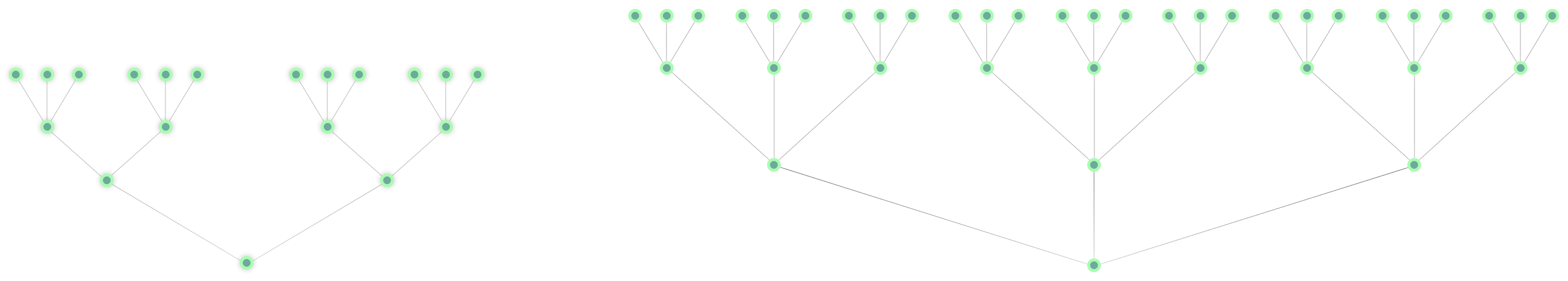

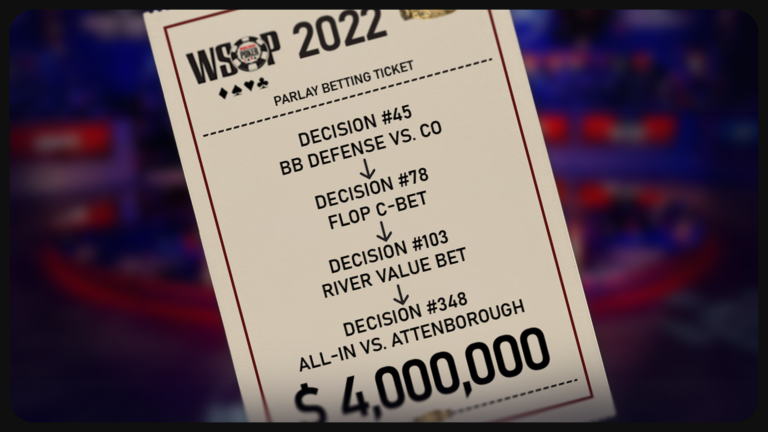

Cash games give the impression that money is won or lost based on the result of a hand of poker, but what we call a “hand” is, in fact, just a bundle of individual decisions. A hand of cash game poker is essentially a parlay of several individual decisions with escalating stakes.

A hand of cash game poker is essentially a parlay of several individual decisions with escalating stakes. Your long-term profit (or loss) is a function of how much EV you gain from each of these decisions, not how many hands you win. Players who do not understand this concept tend to focus too much on protecting themselves from getting drawn out on when they believe they have the best hand on an early street.

Tournaments are a much, much larger parlay. The results of thousands of individual decisions all get packaged into a single payoff. This is why the variance is so much higher. The biggest prizes are much larger than what you could expect to win in a comparably sized cash game, but you are also much more likely to lose your initial investment.

No matter which format you play, your hourly rate will be a function of how many decisions you make in an hour, how much is at stake on the average decision, and how large your edge is on those decisions (measured in EV).

The Big Difference Between Cash and Tournament Poker

In cash game poker, how much is at stake on the average decision is largely determined by the “advertised” stakes of the game. A $5/$10 game will feature larger decisions, on average, than a $2/$5 game, which will feature larger decisions than a $1/$2 game, etc.

In tournament poker, the stakes of the decisions are partly determined by the “advertised” stakes but largely by the stage of the tournament. If you buy in for $1000 and receive 100bb for the first level of the tournament, then you are effectively playing $5/$10 (a bit larger, actually, because of the ante) during that level and should expect a comparable hourly rate.

When the blinds double after a level or two, you will be playing something closer to $10/$20. The average stack will probably not be as deep as in a typical cash game, and that will affect your hourly rate somewhat, but you will be playing a much larger game than $5/$10, even though you will not have taken any more money out of your pocket.

By the time you reach the bubble, with roughly 15% of the field remaining, the average stack will be worth about $6600. The big blind will probably be worth $200–$300. Hundreds of dollars will be at stake in even your smallest decisions. Later in the tournament, every decision will be worth thousands of dollars, and at the final table, they will be worth tens of thousands.

That’s what makes tournament poker exciting and, for the best players, profitable. Those same best players would probably have an even higher hourly rate if they could play a cash game with the same opponents for comparable stakes and with deeper stacks. But they can’t because many of those opponents would never dream of buying into a cash game for tens of thousands of dollars. They bought into a tournament because they thought of it as a $1000 decision, and now, after the run of a lifetime, they’re at the final table, in way over their heads but with no opportunity to take their winnings off the table.

If you’re one of the winning players in the field, the escalating stakes of tournament poker mean your hourly rate grows higher as the tournament goes on.

This is what makes it worthwhile for you to play the earlier stages, when your hourly rate is not as high as what it would be in a big cash game: succeeding at those early levels is the only way into the later levels where your hourly rate will be much higher than it would be in that cash game.

This is also what makes late registration appealing to the best players. In addition to the ICM benefits, it enables them to skip the small stakes where their hourly rate would be lowest. Sure, they’d have a huge win rate in those early levels when measured in big blinds, but the big blind simply isn’t worth very much at those levels. Even if they wanted to use a poker machine to turn those hours into profit, they’d be better served doing so at a high-stakes cash game than in the early stages of the tournament.

Losing players experience the same thing in reverse. When you play poker against superior competition, you are essentially exchanging money for the experience of playing poker.

As the stakes escalate, so too does the amount that losing players are paying for the experience.

That may not seem like a big deal since they only pay the higher fee if they win at the lower stakes levels. But the effect of this is, essentially, to cap their winnings. Should they get lucky enough to win in the early levels, they will eventually lose most of those winnings, without the option of taking them off the table.

A committed gambler could approach cash game poker the same way: sit at a $1/$2 table, move to $2/$5 if they double up, then move to $5/$10 if they double up again, then on to $10/$20, etc. Most choose not to. When they have winning nights, most recreational players choose either to cash out and go home or to remain at the stakes where they are comfortable, neither of which is an option in tournament poker.

The Small Winner

We have not discussed the moderately skilled player, the one who is neither in the top 10% nor the bottom 50% of the field. These players often overestimate their profitability in tournaments by fixating on their edge in the early stages. They see lots of weak players making big mistakes for 100bb in the first level and think, “Wow, I’m way better than these buffoons.”

Indeed, they are. Small winners may have quite good win rates in the early stages, especially because the best players typically have not yet entered. However, because the stakes are so low compared to what they will be later in the tournament, their win rate in those early levels is simply not that important. Like the losing player, the mediocre player has a severely capped upside.

Their prize for crushing the early stages is the obligation to give back some percentage of their winnings to better players later in the tournament.

The WSOP Main Event is a clear example of this. The first day or two offer excellent opportunities to make decisions worth thousands of dollars against some truly terrible poker players. However, should that go well, you’ll eventually find yourself playing for hundreds of thousands of dollars against the likes of Kristen Foxen and Niklas Astedt.

Big Mistakes

All these misunderstandings lead to two big mistakes on the part of less-skilled players:

- They overestimate their edges and

- Underestimate their bankroll requirements

They think that if they can afford to lose $1000, they can afford to play a $1000 tournament. But $1000 is just what your stack is worth in level one! By the end of the tournament, should you be so fortunate, you’ll need to absorb losses of tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars!

More skilled players also make a big mistake, which is that they overestimate the value of playing early levels and small-stakes tournaments. They may fixate on the top prize and think, “Wow, a million dollars for first, such great value!”

But without knowing the buy-in, the top prize doesn’t tell you much. Sure, you could win a million dollars off a $50 buy-in if the field were sufficiently large, but you’d have to get absurdly lucky to do so.

Anyone bankrolled to absorb the variance in such a huge field would probably have a better hourly rate in a higher buy-in event with a smaller field, or in a cash game where they could immediately put several thousand dollars into play instead of needing to run good for hours in the hopes of reaching comparable stakes in the tournament.

At the very least, these players should late register the tournament if they are going to play it. Their objective should be to waste as little of their time as possible on the small stakes, early levels. Of course, they’d have a better chance of reaching the later levels if they played the early ones, but it wouldn’t be that much better. Other poker games will offer more lucrative opportunities for converting that time into money.

This logic applies to satellites as well. A satellite is yet another way of making decisions that will, for a sufficiently skilled player, convert time into money. That they pay out the money in the form of a seat in a larger tournament rather than as cash is, if anything, a strike against them. Cash is strictly better than a tournament seat because you can always buy a tournament seat with the cash if that’s what you most want. Or if it’s not, you can buy something else with the cash!

So, if you want to play a $500 tournament and are bankrolled for it, don’t waste your time in a $50 satellite. You’re going to have a better hourly rate in a higher buy-in tournament or a cash game.

If you aren’t bankrolled for the $500 tournament, well, the satellite isn’t a solution to that problem. It’s just a poker machine that outputs seats in a $500 tournament, seats on which you should not place an especially high value since you aren’t bankrolled for that tournament in the first place.

Just like the early levels of a tournament, a satellite is a small-stakes game where the prize is the obligation to play for higher stakes against tougher competition. If you don’t want the latter, don’t play the former.

Conclusion

If you’re playing poker in any form, you’re presumably motivated by some combination of the money you could win and the experience you hope to have. (Or maybe you have five days to repay a five-figure debt to a Russian gangster with a penchant for Oreo cookies…)

If tournament poker is truly the experience you enjoy and you have the money to play it, then more power to you. But you should understand what exactly the exchange you are making is and what the alternatives are.

Tournament poker appears to offer a much larger potential upside than cash game poker, but for most players, the opposite is true. Tournament poker actually limits their upside by compelling them to keep playing, against tougher and tougher competition, whenever they experience early success.

Even many professionals get fooled by this and focus excessively on how much they could win rather than on the likelihood that they will lose. Yes, you could parlay a $50 buy-in into thousands of dollars, but far more often, no matter how good you are, you will lose the $50. When considering the value of your time, you must factor that likelihood into the equation.

Poker tournaments aren’t magical machines that miraculously convert time to money at much better rates than other poker formats. If you input $50 and three hours into a poker tournament, you should expect to earn (or lose, if you are a less skilled player) roughly the same amount of money you would if you input $50 and three hours into a different form of poker.

You might do a bit better if the tournament attracts weaker competition (as they often do) or if you are a tournament specialist, but it will not be orders of magnitude better. If you have the opportunity to instead invest the same amount of time and a larger amount of money into a cash game, you should expect to find a better hourly rate there.

The reason poker tournaments can offer such large prizes is that they do not allow participants to cash out their winnings.

Before you play one, you should seriously consider whether you are one of the few elite players who benefit from that or one of the many who would be better off if you were allowed to take your winnings at any time, as you are in a cash game.

Author

Andrew Brokos

Andrew Brokos has been a professional poker player, coach, and author for over 15 years. He co-hosts the Thinking Poker Podcast and is the author of the Play Optimal Poker books, among others.

We Are Hiring

We are looking for remarkable individuals to join us in our quest to build the next-generation poker training ecosystem. If you are passionate, dedicated, and driven to excel, we want to hear from you. Join us in redefining how poker is being studied.