Poker Strategies:

Tournaments vs. Cash Games

Tournament poker is not as different from cash game poker as people sometimes assume. Most of what you learn about poker strategy – big concepts like hand reading, value betting, and hand classes – will apply in both formats. If you understand the theory of poker, there is not a lot you need to do differently to adapt from one format to the other, except for understanding ICM, which is a hugely important concept at certain stages of a tournament.

Following are some heuristics that will help you consider how tournament play differs from cash game play. Some of these, such as the presence of antes, are not intrinsic to tournaments but by convention are more relevant in a tournament context. Others, like the value of folding, are central to what makes tournaments tournaments.

Antes Incentivize Wider Ranges

Antes are a common feature in multi-table tournaments (MTTs), but they are not as common in cash games. However, it is possible to find some cash games that do use antes, and some MTTs that do not. Despite this, antes are often seen as one of the main distinguishing factors between MTTs and cash games, and this is one reason why pre-flop strategies can vary significantly between the two formats.

Antes are a type of forced bet that all players are required to pay before the start of the hand. Antes increase the size of the starting pot, which gives all players a larger prize to fight for and can incentivize them to play more hands from every position. This is especially true for the big blind, whose calls typically close the action. Antes cause players to contest pots with weaker hands compared to a game without antes.

Antes increase the size of the starting pot, giving all players a larger prize to compete for, incentivizing players to contest pots with weaker hands

The source of the ante is not important, only the size. Whether a single player (typically the BB) antes an amount equal to the big blind or eight players each ante an amount equal to ⅛ of the big blind, the amount of chips in the pot will be the same. So there is no strategic difference between these formats. Unlike the big blind, which is live and counts toward the BB’s pre-flop wager, antes are dead money. Once they are in the pot, it does not matter who paid them or where they came from.

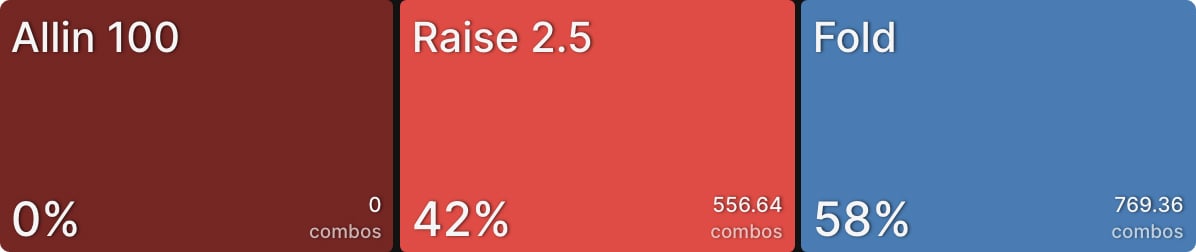

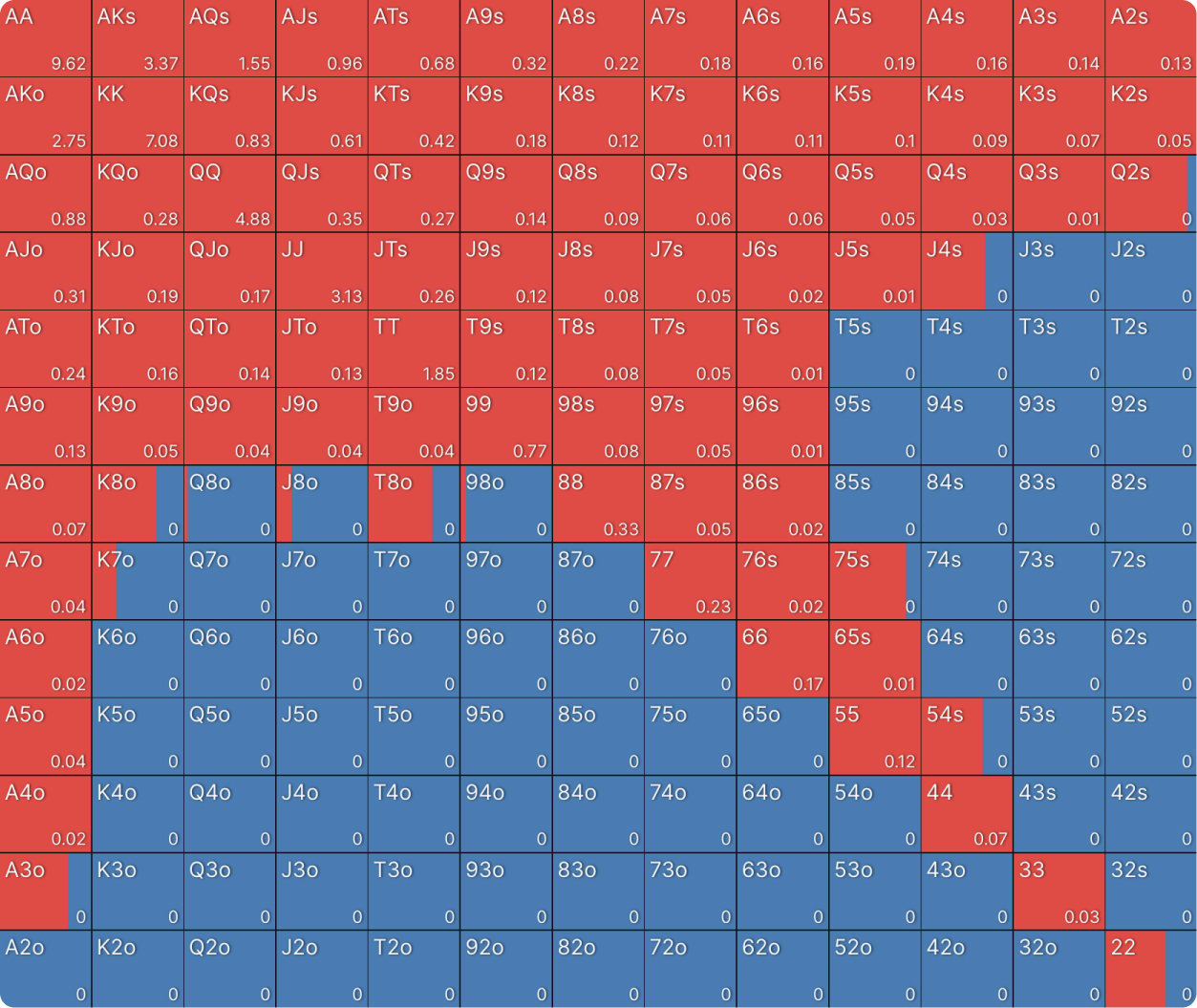

Compare this to the BTN’s range for opening 2.5BB in a six-handed MTT with 100BB stacks and an ante:

BTN opens 42% of hands in the cash game compared to 53% in the MTT. Notice that the EV of all hands is also higher in the MTT because there is more money in the pot. Opening Aces is worth 13.29BB when antes are in play but only 9.62BB without antes.

This effect is even more dramatic for the big blind, who closes the action and has the option to contest the pot at a discount. When any other player considers entering the pot, they must assess not only the amount they will wager relative to the pot but also the risk of other players behind them calling or re-raising 🙋♂️ This forces them to play tighter than pot odds alone would dictate. In a single-raised pot, the BB’s call closes the action, so pot odds more directly determine which hands will show a profit.

More money in the pot also increases the value of the chips BB has already invested 💰 In a cash game, the BB must call 1.5BB into a pot of 4BB. Facing the same raise in an MTT, they must call 1.5BB into a pot of 4.8BB. In an 8 or 9-handed MTT, the ante would typically be larger still, and the BB would be incentivized to play even weaker hands.

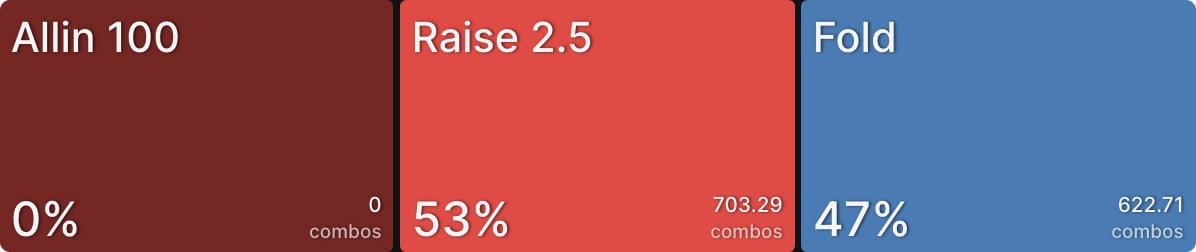

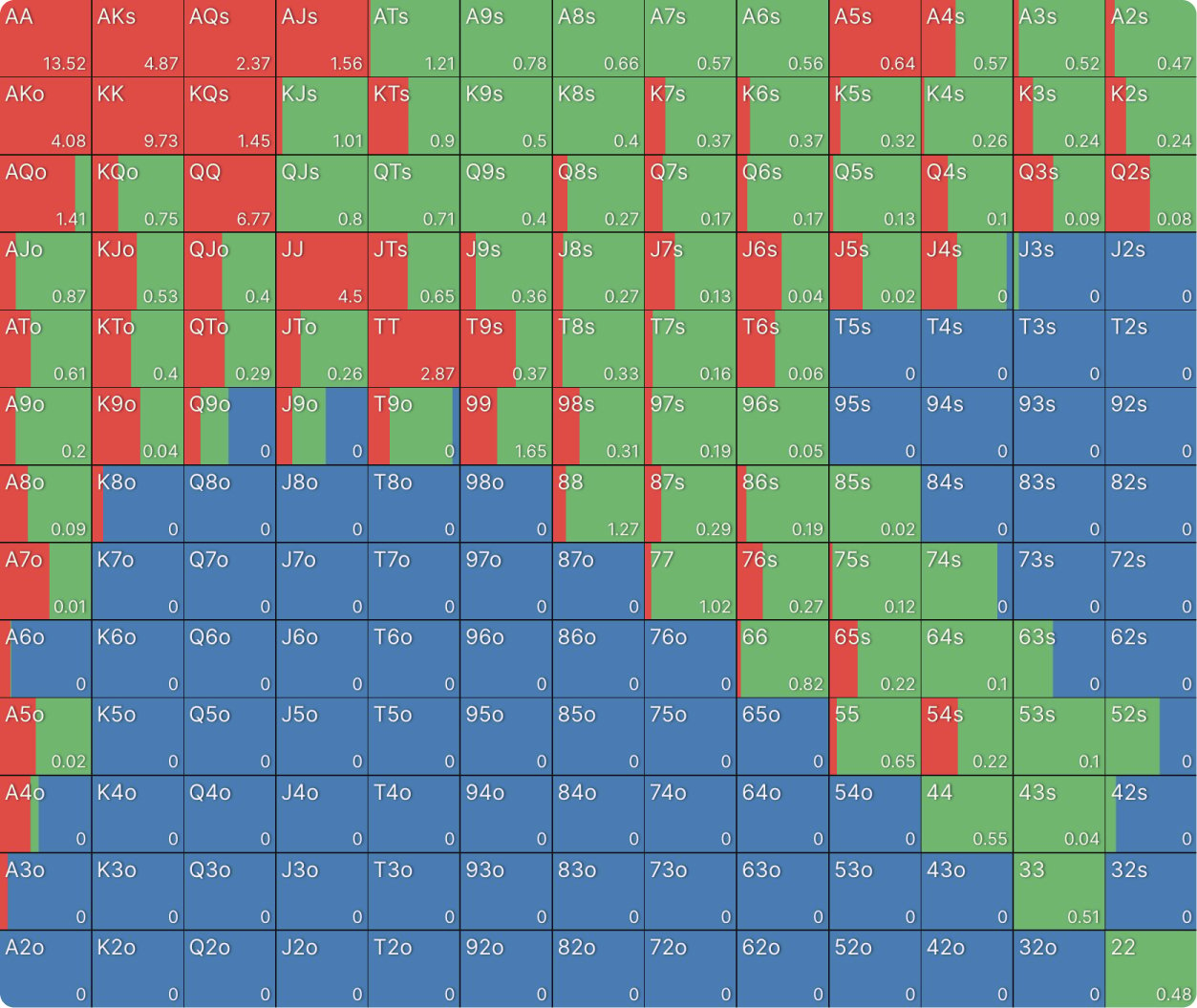

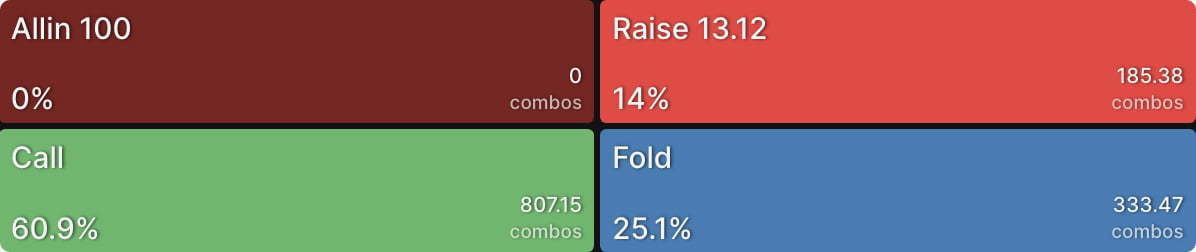

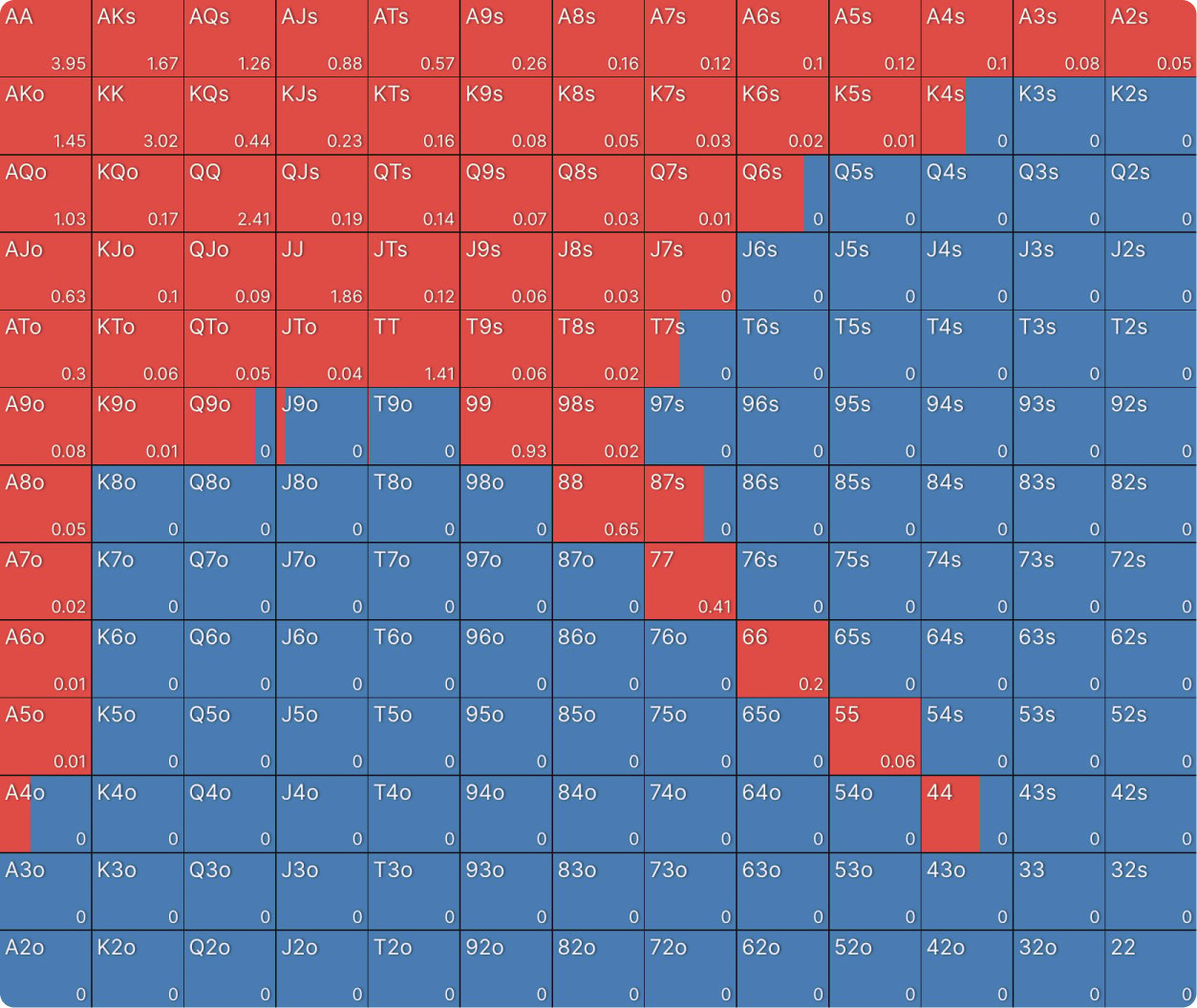

Here is BB’s response to the BTN raise in the cash game. They call ~26% of hands and raise ~14%, for a total VPIP (Voluntarily Put Money in Pot) of ~40%:

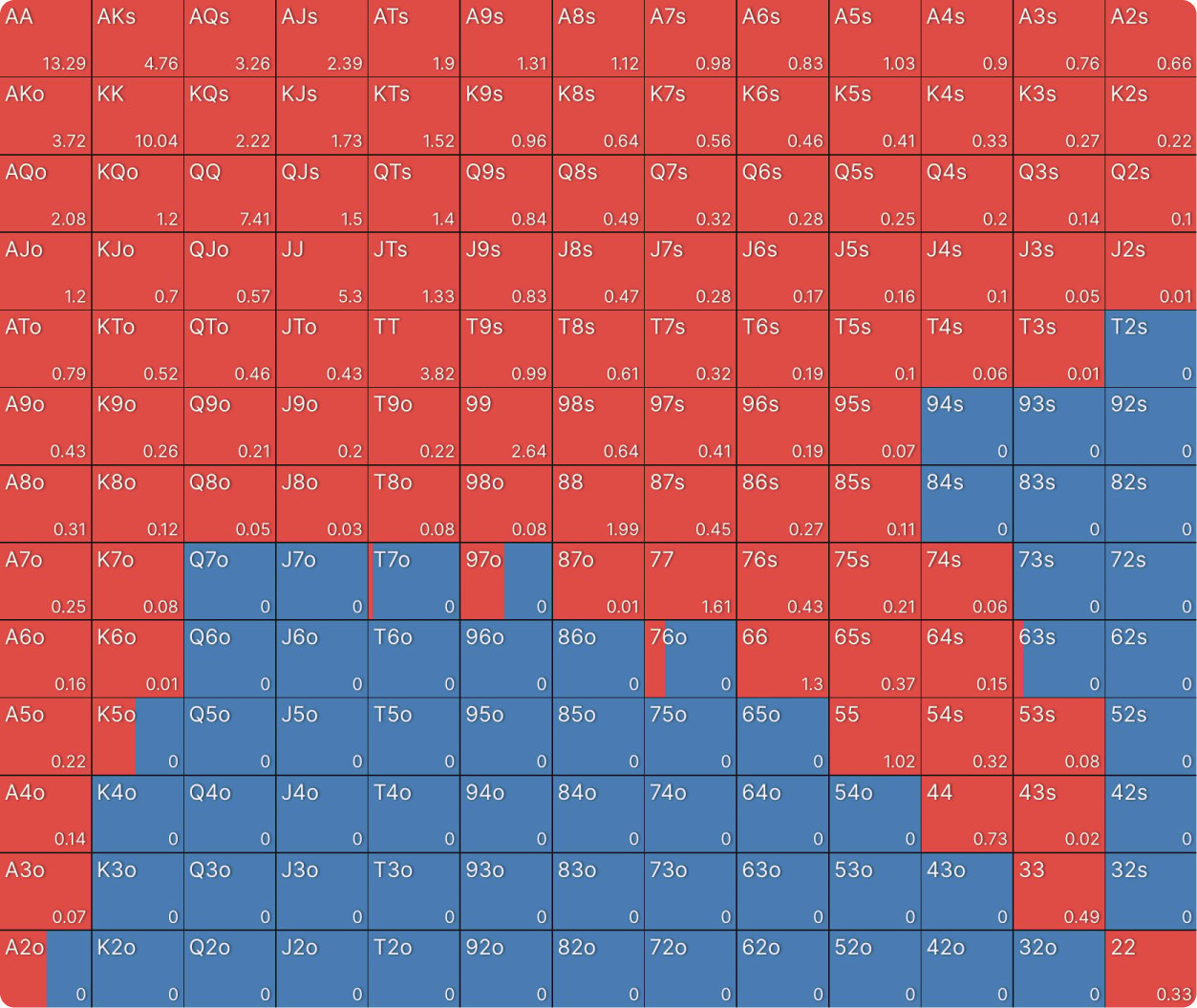

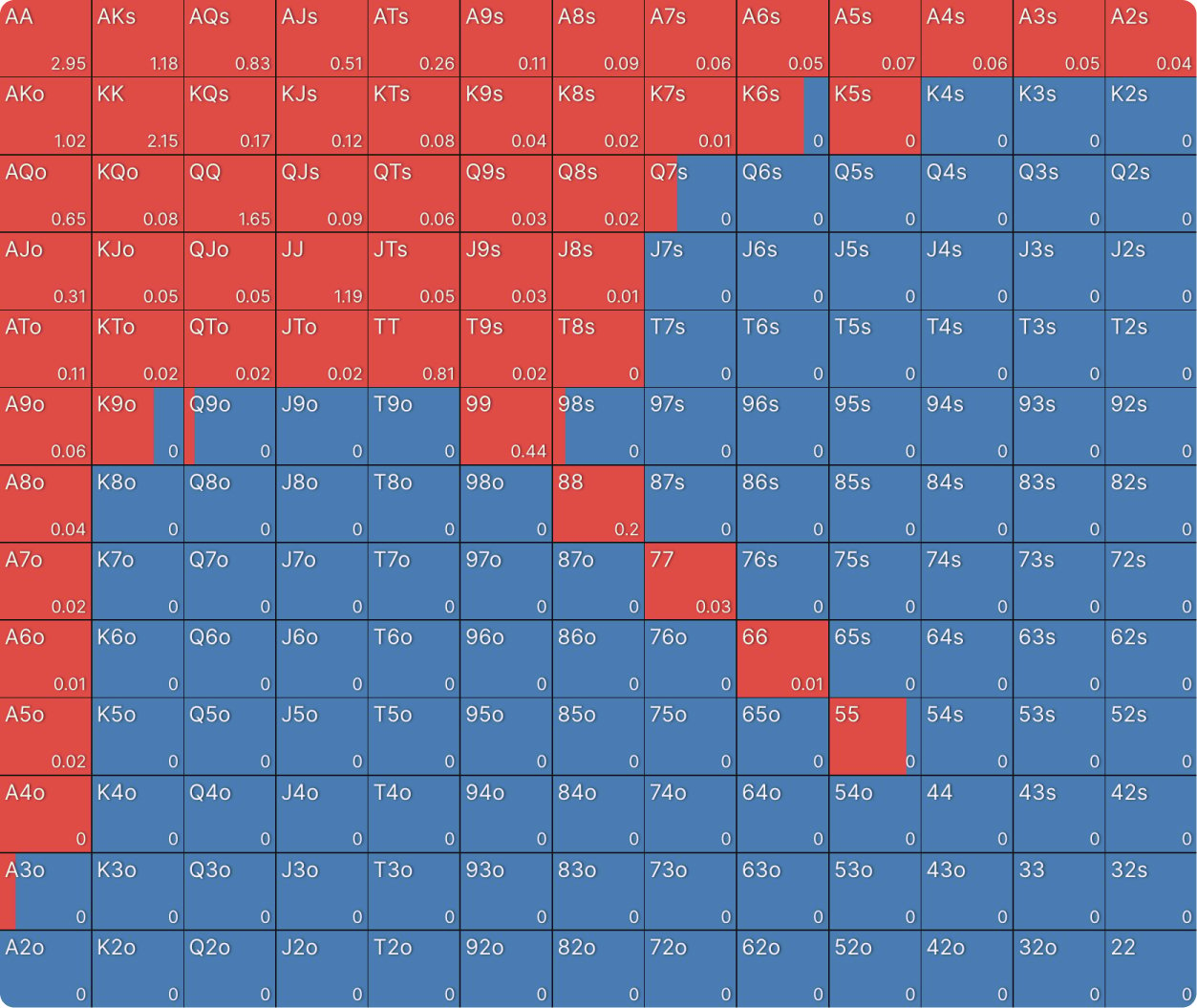

In an MTT with antes, the BB again raises ~14% of hands (though the composition of this raising range is somewhat different) but calls ~61% of hands, for a total VPIP of ~75%, nearly twice what it was in the cash game without antes.

One final note

These tournament charts are based on ChipEV models. As we will see, some of the other distinguishing features of MTTs incentivize players to value their survival in addition to chips won or lost, and that incentivizes more conservative play. Even so, the general point holds: antes incentivize all players to contest the pot with wider ranges than they would in an identical scenario without antes.

Stack Size Dynamics

Because of the rising blinds and inability to reload more chips, you are more likely to see a wide range of stack sizes at your table in an MTT than in a cash game. You are also more likely to encounter shorter stacks in general, and to see your own stack size fluctuate in strategically significant ways. Thus, understanding the strategic implications of a larger or smaller effective stack as well as of various stack distributions around the table is a far more important skill in MTTs than in cash game play.

The most important thing to understand is the power of moving all in, which enables a player to deny equity to opponents while guaranteeing full equity realization for themselves. With all but your strongest hands, you will be incentivized to find opportunities for moving all in yourself while avoiding situations where opponents can easily deny you equity by moving all in on you. You can learn more about these tactics in this article.

A useful heuristic is that the shorter stacks at the table usually have an advantage because of their reduced risk of moving all in. With short stacks behind you, you must play somewhat tighter than you otherwise would because of the risk of one of them moving all in. When you are one of the shorter stacks at the table, you can move all in somewhat wider than you would if everyone had a stack of your size, because players who call your shove will not be all in themselves.

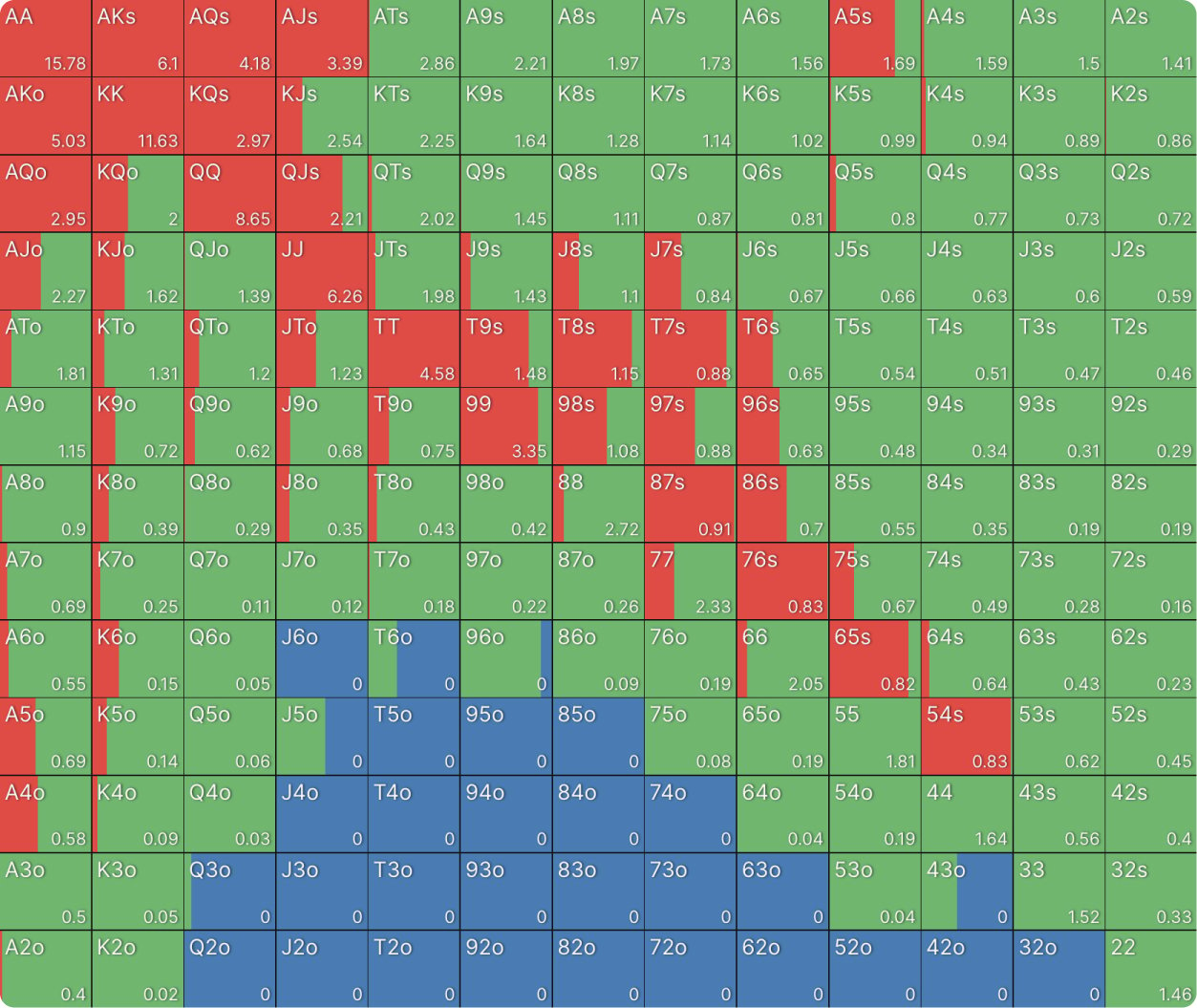

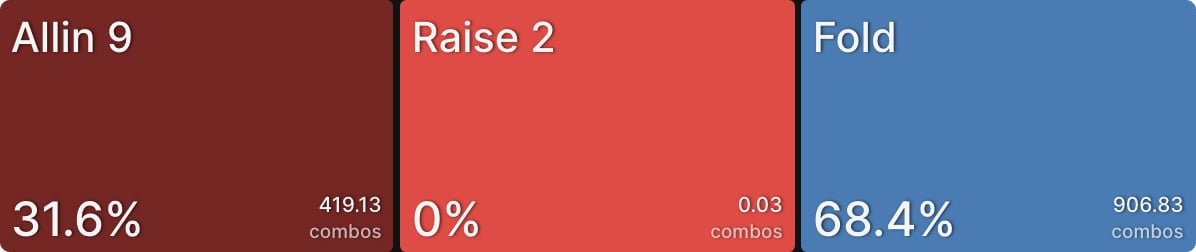

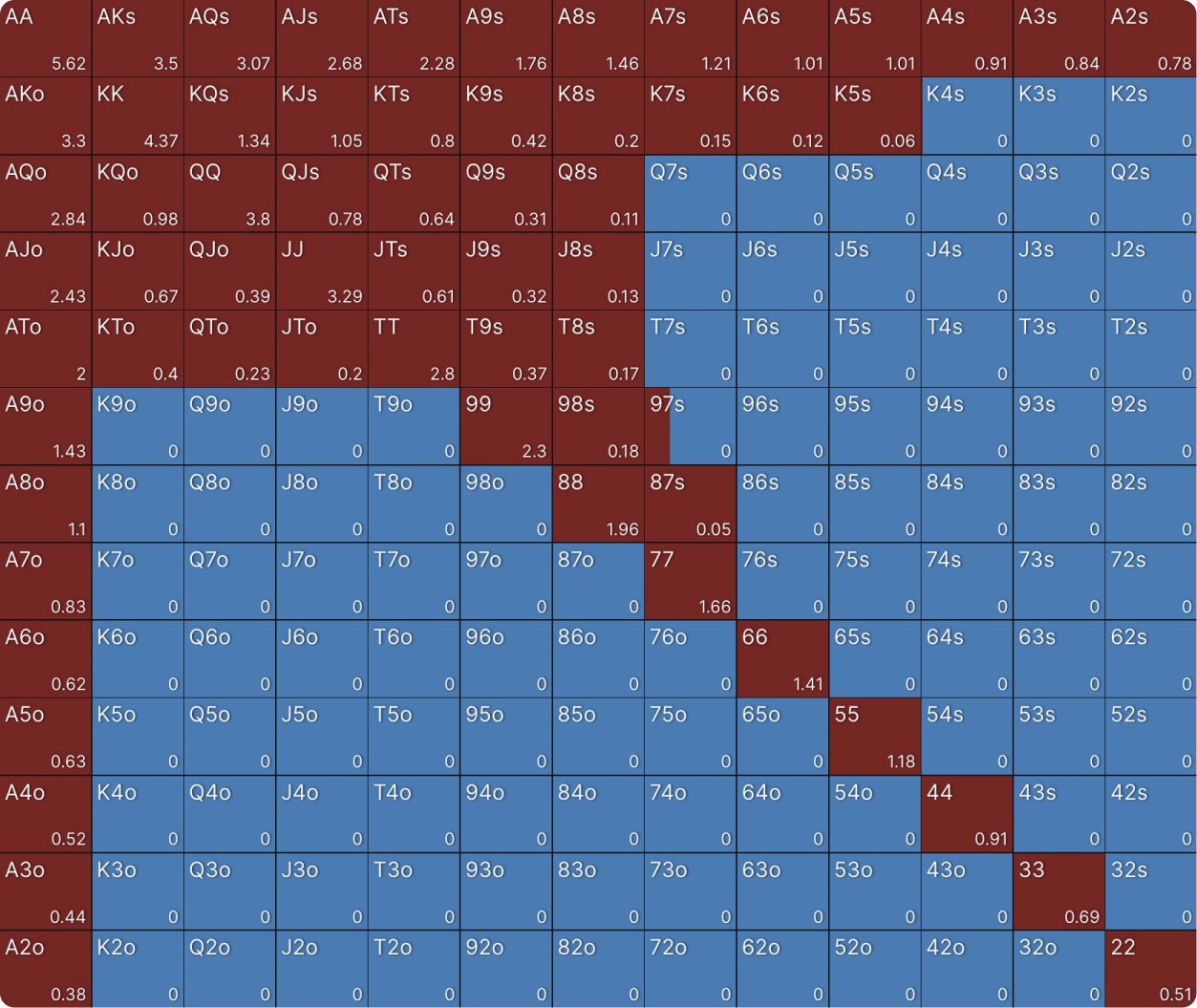

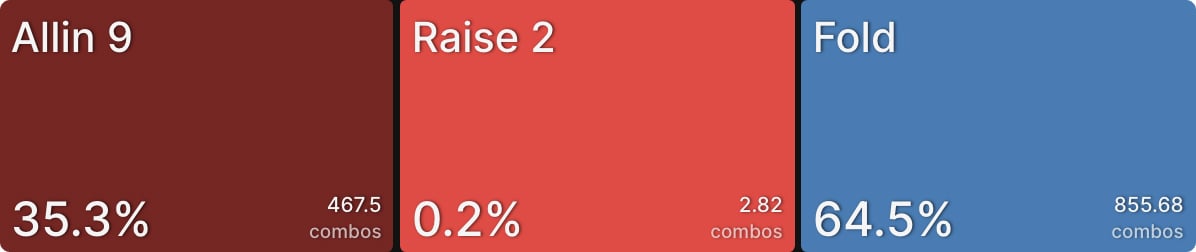

When all players have 9BB, the CO shoves 31.6% of hands:

When the players behind have deeper stacks (29, 21, and 32BB, respectively), the CO can shove 35.3% of hands. CO risks the same 9BB in both scenarios, but the players behind must take on greater risk when they have more chips. If the SB calls the shove, they are putting in nearly half their stack and so effectively committing 21BB to the pot should the BB wake up with a strong hand.

Notice that CO pushes wider when players behind them are deeper? 🤔‼

The BTN has room to call and still fold some hands to a BB shove, but even that comes at a cost. Those hands the BTN folds have a chance of winning, which means they lose equity when they fold to BB. The risk of being denied that equity discourages calls from some hands that could have called if BTN also had just 9BB.

This does not mean a short stack is more valuable than a larger one. On the contrary, a player with more chips is more likely to win a larger prize, so the cash value of their stack is greater. However, when contesting a pot, the short stack does enjoy some advantages that make it a bit easier for them to accumulate chips.

Folding is +EV

In a cash game, if you fold, you win nothing. That means any play with a positive expectation, no matter how small, is better than folding. In a tournament, survival has value. That means folding has a positive expectation, not $0 as in a cash game.

In a tournament, survival has value.

Whenever another player is eliminated, the value of your stack increases, even if you were not the player who took their chips. You are now that much closer to locking up the next prize. The closer you are to a pay jump, the more it’s worth it to you to fold and let other players take risks against each other.

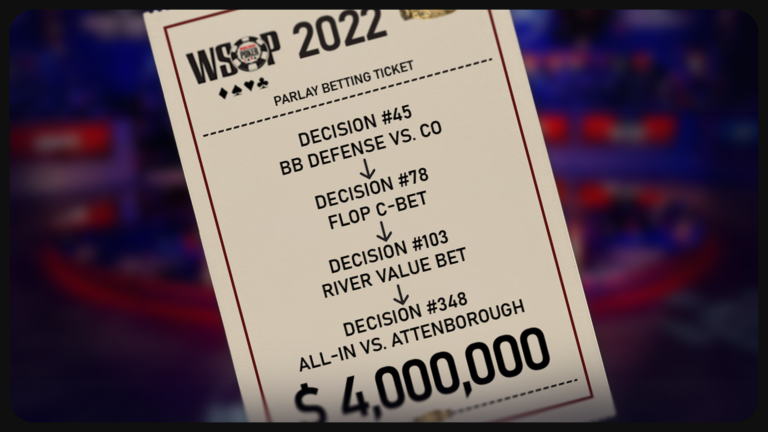

You should only contest a pot by calling or raising if you believe the EV of doing so to be greater than the EV of folding. Although you will not be able to calculate these values precisely at the table, you can build intuition around them by studying charts calculated using the Independent Chip Model, or ICM.

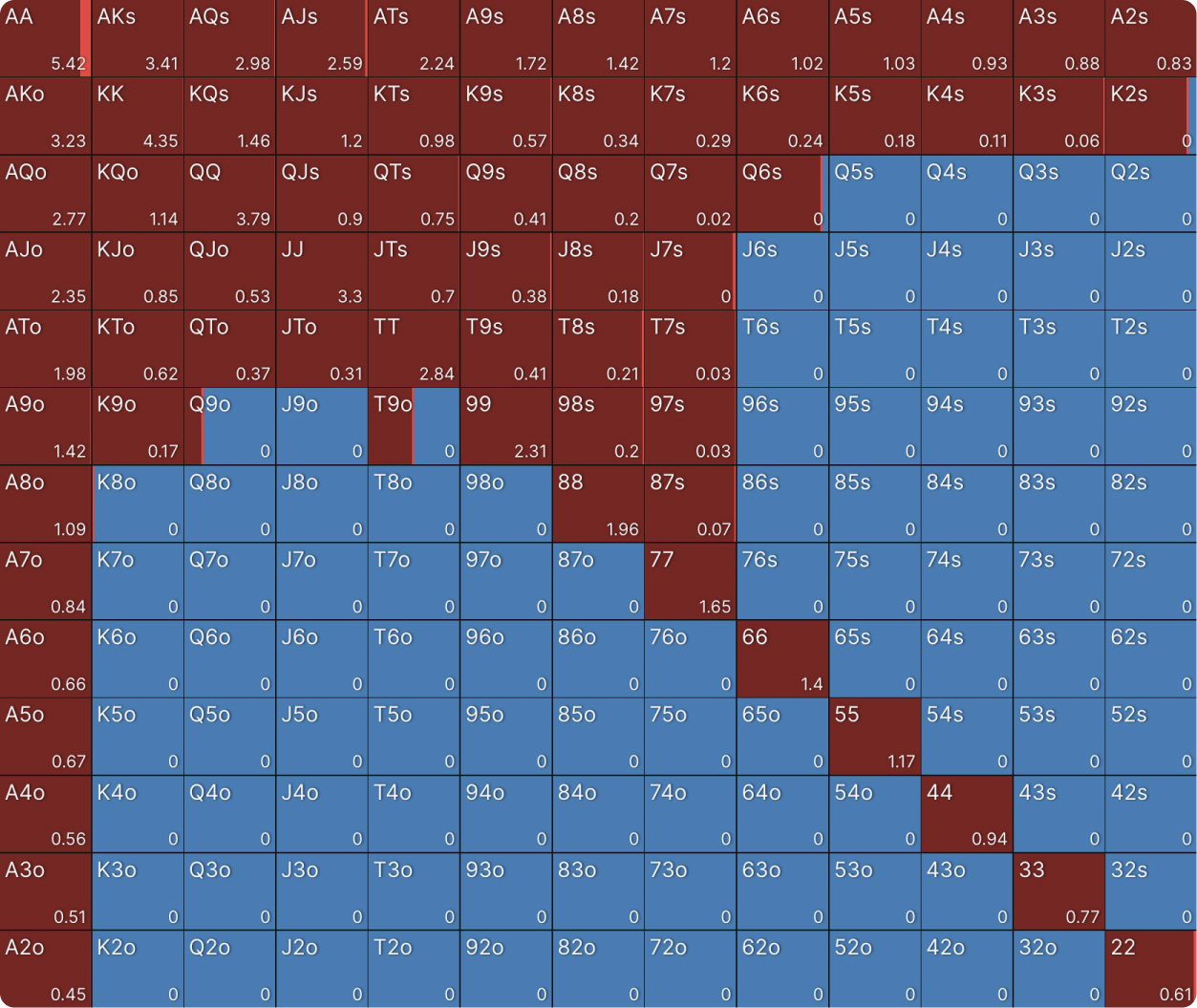

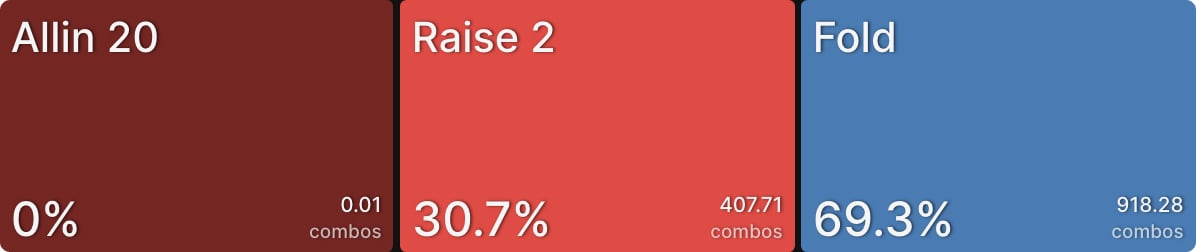

Here is the CO’s opening strategy with 20BB stacks and 50% of the field remaining, which raises 30.7% of hands:

Compare this to the CO’s opening strategy with 20BB stacks and 25% of the field remaining:

CO tightens up to 28.6% of hands, and hands that were at the margins of their opening range with 50% remaining (44, K4♠, Q6♠) now strictly prefer to fold. Slightly stronger hands (55, K6♠, Q7♠), which were pure opens with 50% remaining, are now on the margins and indifferent between raising and folding.

This reflects not so much a reduction in the value of opening these hands as an increase in the value of folding them.

ICM EV is measured as the change to your table equity percentage compared to folding. Table equity percentage is your portion of the table’s $EV in a tournament. For example, if your stack is worth $100 after folding, and the sum of the $EV value of everyone’s stack at your table is $1000, then your table equity percentage is 10%. In the picture above, AA has an EV of 2.95, meaning you’d increase your table equity by 2.95% after raising.

This may seem like a modest difference – the CO opens only about 5% tighter in the second scenario–but keep in mind that with 25% of the field remaining, the first pay jump, the bubble, is not especially close, and already we see CO adjusting with slightly more conservative play. There are extreme examples on the exact bubble where folding KK or even AA can be correct.

You will only be able to approximate the value of folding in a given situation, but it is valuable to know how to do so. Following are the major factors that determine the value of folding.

Factors That Determine the Value of Folding

- Proximity to a pay jump – The closer you are to locking up a larger prize, the more incentive you have to avoid risk until it is locked up. The larger the pay jump, the greater your incentive.

- Presence of short stacks – The value of folding lies in the possibility of other players getting eliminated before you. The more short stacks there are in the field (not just at your table), the more value there is in folding and giving them the opportunity to bust before you.

- Your stack size – The more chips you have, the less likely you are to lose them all in a given hand, which reduces your incentive to fold. This is especially true if no one else at your table covers you.

- Players remaining – The incentive to take risk is to accumulate chips and give yourself a better chance of winning one of the largest prizes for the top few finishers. The closer you are to those prizes, the more incentive there is to take those risks. When dozens or even hundreds of players remain, accumulating chips does not greatly increase your odds of winning a large prize, so you have less incentive to take risks.

- Opponent Skill – If the other remaining players understand tournament strategy, they will share your risk aversion, making it less likely they will take risks against one another after you fold. If you believe other players will take incorrect risks, this increases the value of folding for you.

Your Last Chips Are The Most Valuable

There’s an old saying that all you need to win a tournament is a chip and a chair. As long as you remain in the tournament, no matter how short your stack, there is a chance you will win a prize. There is even a chance you will win the whole thing – Greg Merson won the 2012 WSOP Main Event after being reduced to just a few big blinds on Day 5. Another way of conceptualizing this is that your last chip is the most valuable, and each subsequent chip added to your stack is worth somewhat less.

Your last chip is the most valuable, and each subsequent chip added to your stack is worth somewhat less.

In a cash game, if you have one hundred $5 chips, your stack is worth exactly $500. If you lose half of them, your stack will be worth $250. If you double up, your stack will be worth $1000. The value of these chips is linear.

Not so in a tournament. If you bought into a tournament for $500 and received 500 chips, your stack would be worth $500 (ignoring rake). If you doubled up to 1000 chips, however, your stack would be worth less than $1000. The new chips you added are worth less than the ones you already had. Conversely, if you lost half your stack, your remaining 250 chips would be worth more than $250, because you still have the most valuable chips, which are the last ones.

It follows from this that you should be especially conservative as a short stack. While it can be frustrating and boring to grind a short stack, especially if you ended up short as a result of a bad beat, it is important to recognize those last few chips still represent a lot of equity and should be invested with care. “Rounding to zero” or throwing the last of your chips all in on the first halfway decent hand you see is an expensive mistake.

We have seen that short stacks enjoy an advantage over their opponents. That means you will find a profitable opportunity to invest the last of your chips if you are patient. There is no reason to take a subpar spot out of desperation. If you keep getting dealt bad cards, and someone raises in front of you whenever you get decent ones, you should keep folding 👐

Eventually, one of two things will happen:

Either you will get a good opportunity (your next hand could always be Aces!)

or

You will blind down to the point where more and more hands become profitable investments.

When you have just a few blinds left, you can play almost any hand from any position profitably thanks to the antes. Of course, you hope a better opportunity will come along before that, but if it does not, the best thing you can do is fold and wait 👌⌚

Conclusion

Tournaments may seem more fast-paced and action-oriented than cash games, but this is often due to the presence of short stacks and antes, which encourage players to contest more pots. If we were to compare cash games with comparable stack sizes and antes, we would see even more action because there would not be the same incentive for risk aversion and survival.

Knowing when to take risks and when to let others take risks is what separates skilled tournament players from those who only understand the general principles of poker theory.

Author

Andrew Brokos

Andrew Brokos has been a professional poker player, coach, and author for over 15 years. He co-hosts the Thinking Poker Podcast and is the author of the Play Optimal Poker books, among others.