Exploitative Dynamics

GTO solutions are designed to be unexploitable, performing reasonably well no matter how your opponents play. They achieve this by assuming that when there is a best option with a given hand, your opponents will make that play. Thus, the GTO approach is to play in a way that minimizes the amount and profitability of good options available to your opponents.

In other words, GTO solutions do not incorporate or rely upon any assumptions about mistakes your opponents will make. This makes them robust against any strategy, no matter how unpredictable, your opponents might throw at you. However, it also limits their ability to profit from any mistakes your opponents do make. To be clear, GTO strategies will profit from many common mistakes; they just won’t profit as much as an exploitable strategy designed to take maximum advantage of those mistakes.

GTO strategies will profit from many common mistakes; they just won’t profit as much as an exploitable strategy designed to take maximum advantage of those mistakes.

When you can predict specific mistakes your opponents will make, you should deviate from unexploitable play in order to take advantage of those mistakes. This is not a violation of GTO. It is the same thing a solver would do if you were to “teach” it about the mistakes you planned to exploit (which you can via nodelocking).

Mixed Strategies and Sensitivity

Some parts of a GTO strategy are more sensitive to your opponents’ response than others. For example, raising AA on the BTN will certainly be the best play in a 100bb cash game, regardless of who’s in the blinds. Folding 72o in the same spot will also be the best play, absent some very big mistakes from the players in the blinds. But hands like A3o or T4♠ could go either way, depending on how the blinds react to your raise.

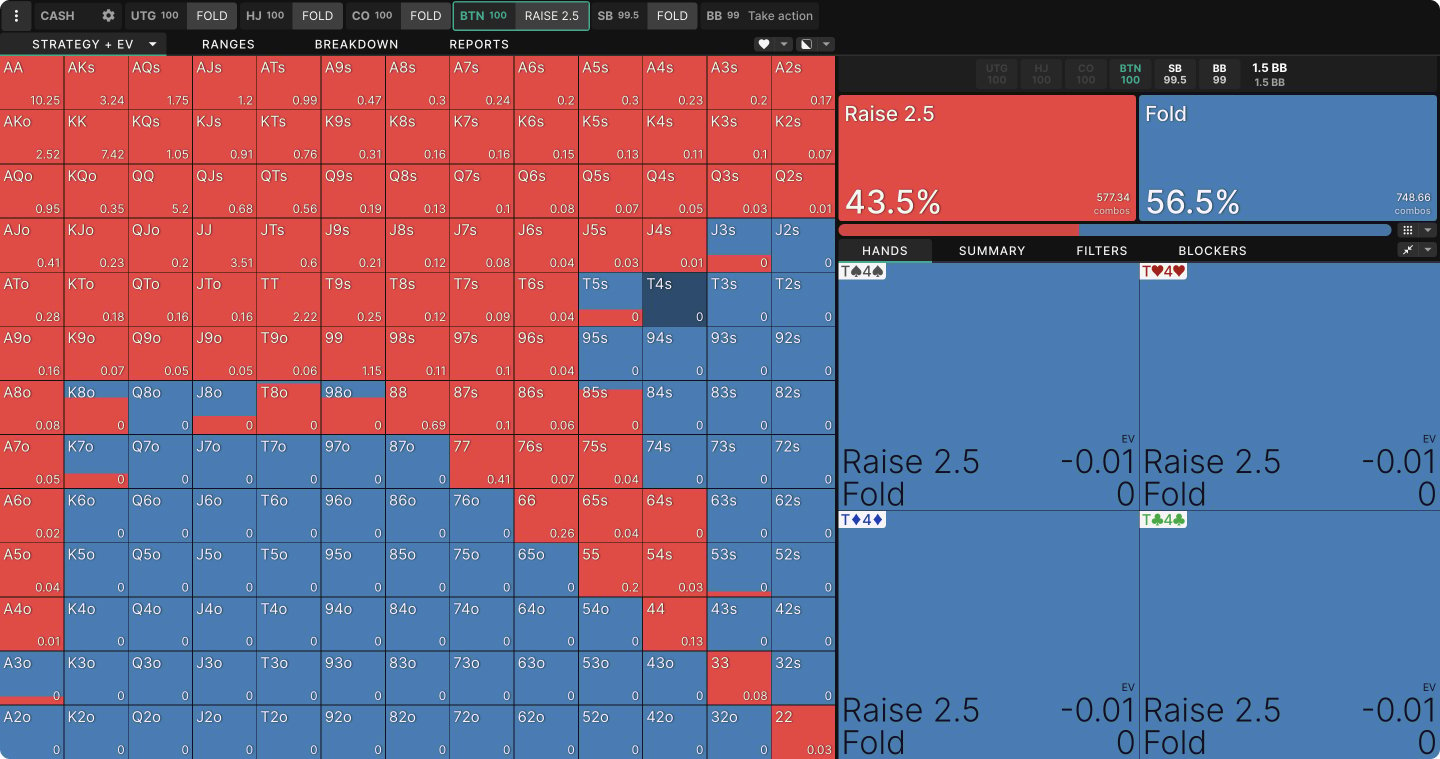

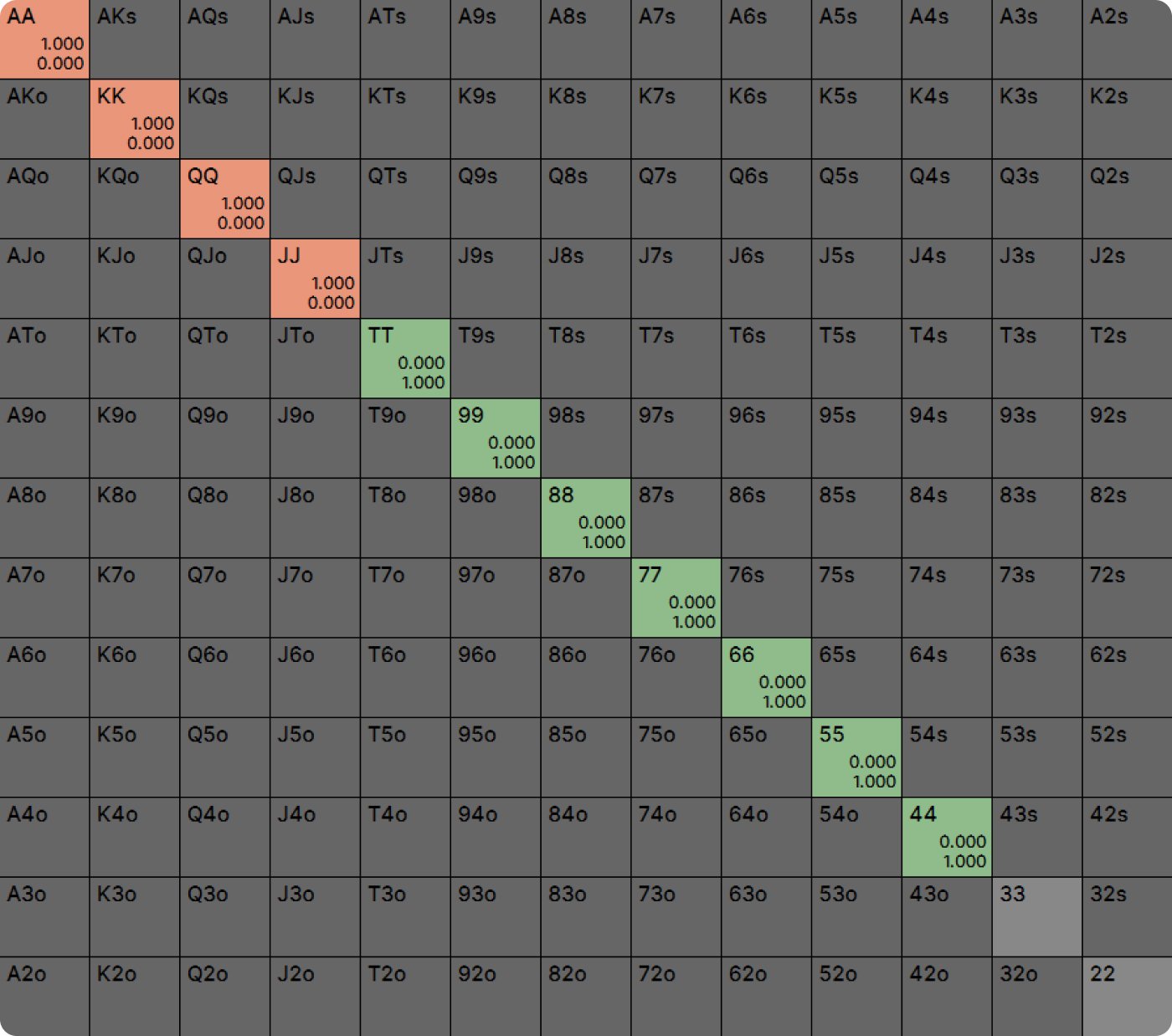

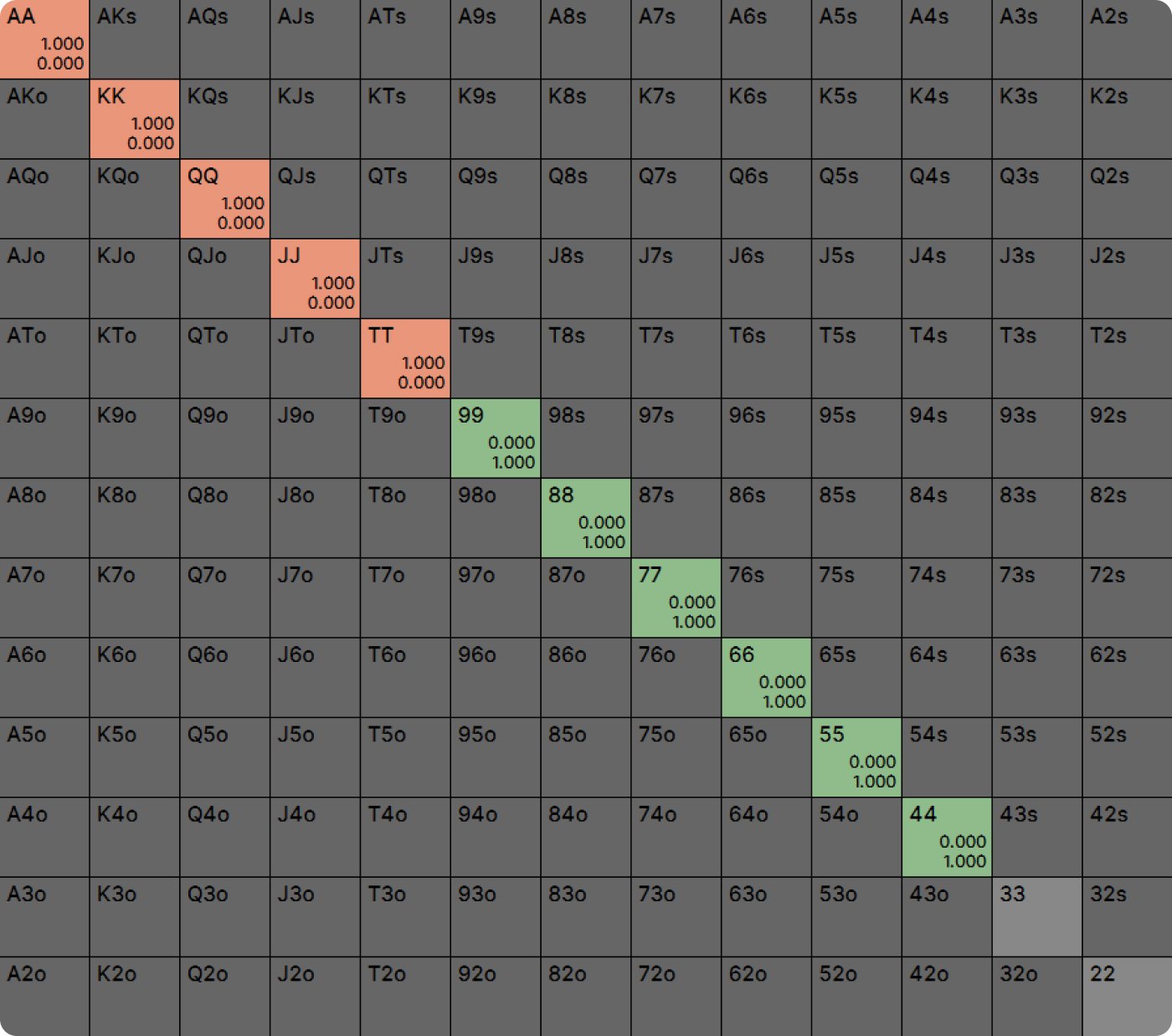

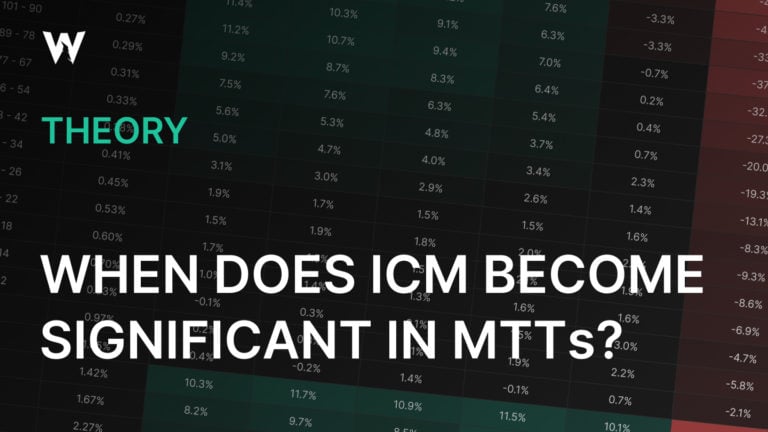

How do we know this? Have a look at the chart below, which shows BTN’s opening range. The number in the lower right of each box is the EV of that hand if your opponents respond perfectly.

Of course, with Aces the decision is not close, but this is true for many lesser hands as well. ATo and J8♠ are such profitable opens at equilibrium that they show a profit no matter how the blinds respond. Even if the blinds call or three-bet more than a solver would, these opens will still be profitable. They may even gain EV! Conversely, 72o is so far from being a profitable open that even if the blinds call or three-bet somewhat less than optimally, you are still unlikely to show a profit with it.

For many hands, however, raising and folding have similar EVs at equilibrium, which means either option could be superior if your opponents do not respond perfectly. For any mixed strategy, the EV of all options in the mix must be identical. If they weren’t, the solver would prefer one action over the other. This means even a slight deviation from your opponents could make one option more profitable.

Even pure strategies can be quite sensitive, however. Notice the EV of opening T4♠ into blinds who will play perfectly is only -0.01 bb. If the blinds fold too often, or if they do not three-bet enough, allowing you to realize more equity than the solver expects, this could become a profitable open. Conversely, even T6♠, which the solver shows as a pure open, could become unprofitable and therefore a pure fold against blinds who 3-bet too often. The closer the hand is to the thresholds, the more sensitive it is to the responses of the players behind you.

The Four-Step Exploitative Process

In my book, Play Optimal Poker, I recommend a four-step process for exploitative thinking:

1) Envision the Equilibrium

Ask yourself, “How would this hand play out if my opponents and I were replaced by game theoretically optimal supercomputers?” You aren’t a game theoretically optimal supercomputer, so you won’t be able to answer this precisely, but you should consider factors like:

- Which player should be more inclined to bet?

- What kind of range should each player bet?

- Which are the best hands for each player to value bet?

- If I bet, what should my opponent’s raising range look like?

- What are the weakest hands with which my opponent ought to commit his entire stack?

Once you have a sense of what your opponent’s equilibrium strategy ought to look like, it will be easier to envision how they are likely to deviate from it. Then, you can think about how to take advantage of those deviations.

Once you have a sense of what your opponent’s equilibrium strategy ought to look like, it will be easier to envision how they are likely to deviate from it.

If you’re new to game theory, this will probably be the hardest step in the entire process. The good news is that it’s not an all-or-nothing proposition: even if you get only the rough contours correct (“I should mostly check, and my opponent should mostly bet”) that’s still a big step up from not thinking about the equilibrium at all. With practice, experience, and study, you’ll get better and better at envisioning equilibria.

2) Make a Read

Ask yourself, “How is my opponent deviating from the equilibrium?” Be explicit about this, and as specific as you can. “They’re calling too often with pure bluff-catchers on the river,” is more useful than “They’re too loose” or “They’re a fish.” It’s OK if all you have are hunches. It’s rare to have a surefire read, just as it’s rare to have a surefire winning hand. Poker is fundamentally a game about making decisions under conditions of uncertainty. Later in the process, we’ll account for your confidence in your read.

3) Identify the Exploits

Once you identify a likely deviation from the equilibrium strategy, ask yourself, “What can I do to exploit this mistake?” Once again, you want to be as precise and specific as possible. You also want to be creative, as there is often more than one potential exploit for a particular mistake.

4) Determine the Degree of Deviation

Ask yourself, “How far should I deviate from the equilibrium?“

Suppose your opponent doesn’t seem to bluff enough on the river, and you plan to exploit them by folding more often. The next step is to determine how much more often. Does this just mean folding when the decision would otherwise be close? Is it as extreme as folding the second nuts? Or is it somewhere in between?

There’s a strong situational component to this – it’s harder to find bluffs on some rivers than on others – but two factors you can consider in advance are the magnitude of your opponent’s mistake and the degree of confidence you have in your read. Remember that in order to exploit an opponent who seems to be deviating from his equilibrium strategy, you must deviate from your own equilibrium. This, in turn, raises the possibility that you will be exploited if you are wrong about your read.

The larger your deviation from the equilibrium, the greater the penalty for being wrong, which is why larger deviations require stronger reads.

Demonstration

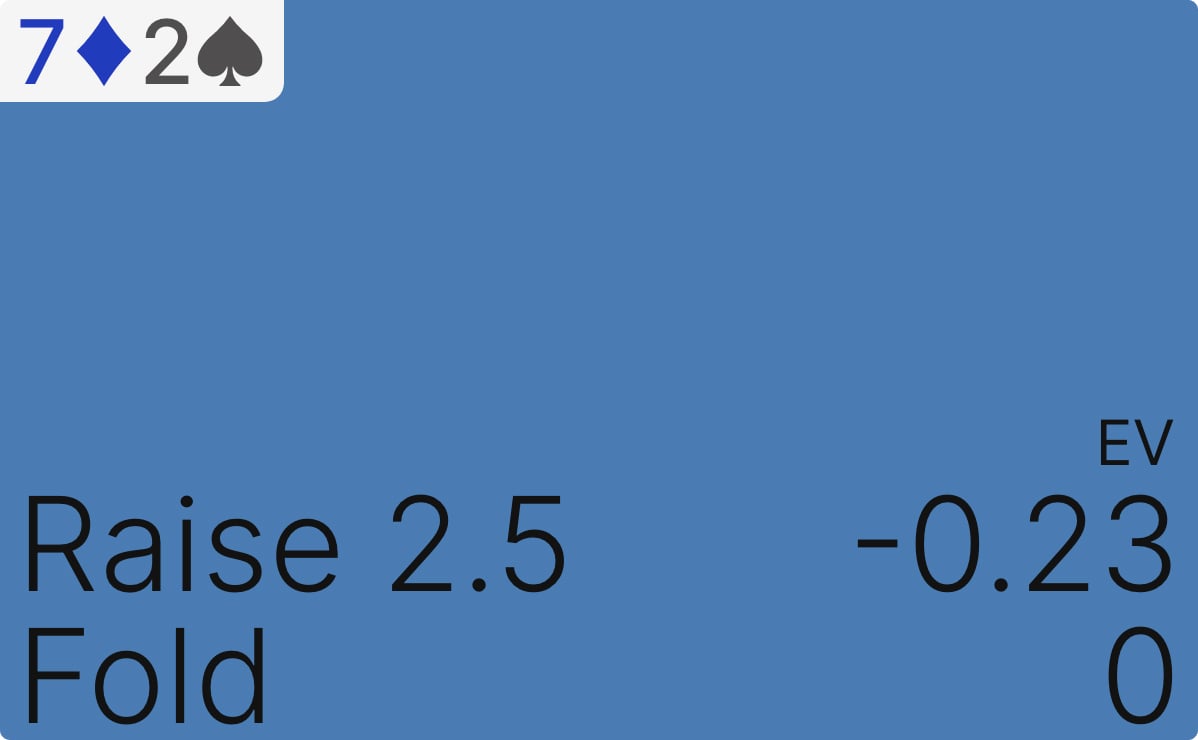

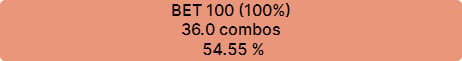

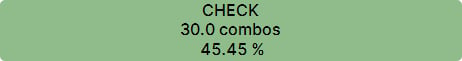

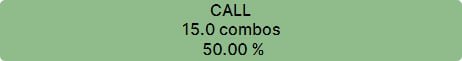

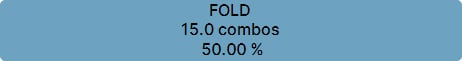

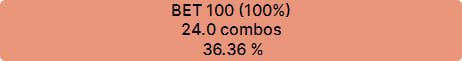

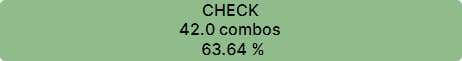

Let’s consider a simplified river scenario where the final board is 22223. The IP player has a range of 44-AA, while OOP has only the middling hands in that range, 77-JJ. There is $100 in the pot. IP may either bet $100 or check. If they bet, OOP may call or fold (even if they were allowed to bet or raise, they would never want to do so).

IP’s equilibrium or GTO strategy is to bet anything JJ or better and to bluff with some combination of 44, 55, and 66 (it doesn’t matter which, as all are equally worthless) at a frequency that makes OOP indifferent to bluff-catching.

The value bets are all pure strategies, which means betting is definitively better than checking. Even JJ, the thinnest value bet, makes $133.92 by betting as opposed to $98 from checking (it does not win quite the full pot by checking because it occasionally chops with OOP’s JJ).

The bluffs are all mixed strategies, which means betting must have the same EV as checking, $0 in this case.

OOP must reach a calling frequency of 50% to make IP indifferent to bluffing (very slightly less here because of the blocking effect from JJ). JJ is a profitable call because it blocks some of IP’s value bets, the rest are pure bluff-catchers and indifferent between calling and folding.

Although both players have 50% equity, IP’s EV in this game is $67.70, well over half the $50 pot. This is true despite OOP playing as well as they possibly could. The opportunity to bet a polarized range is inherently valuable, no matter how your opponent responds.

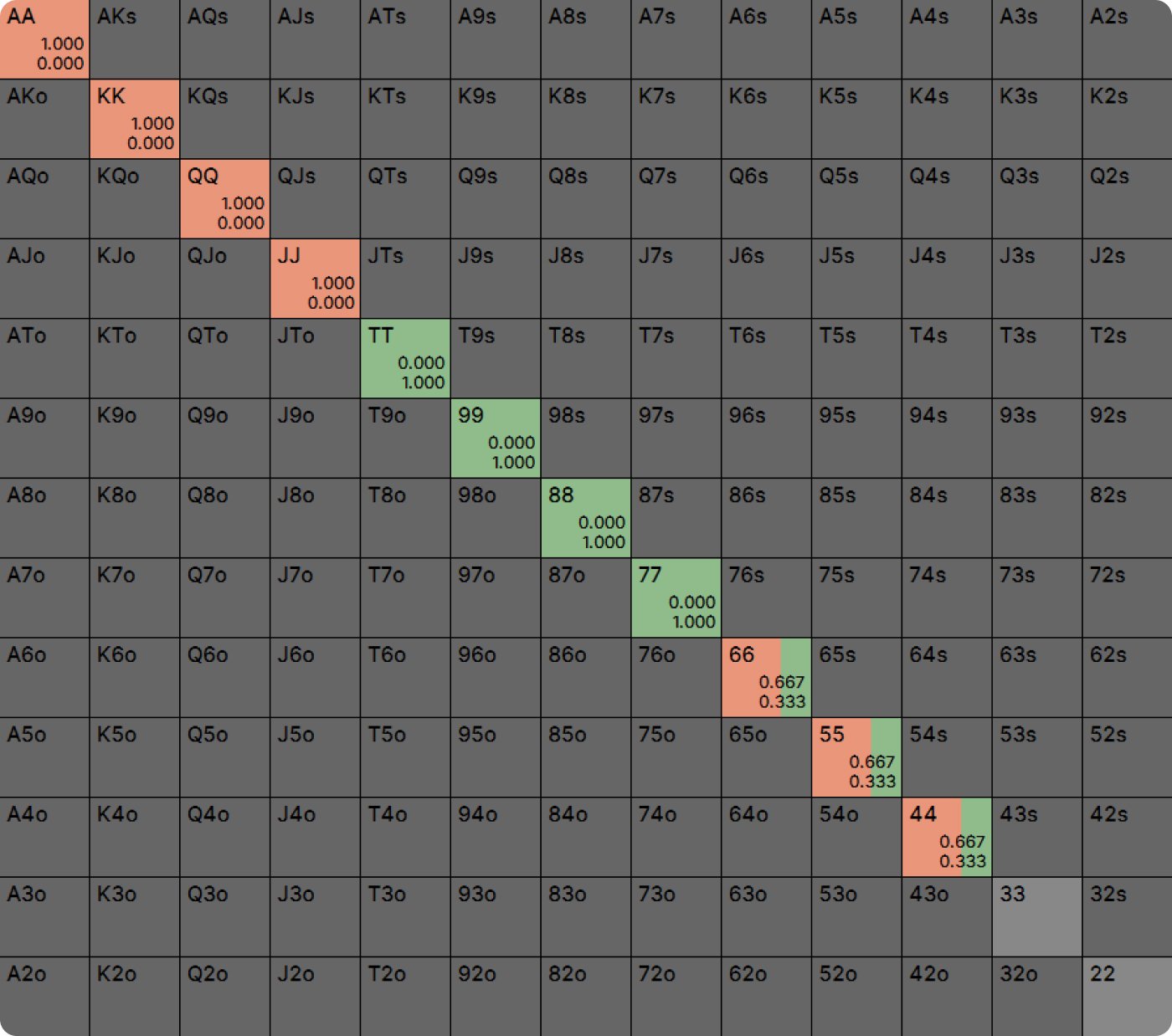

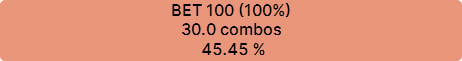

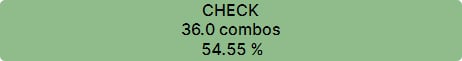

What do you expect to happen if we node lock OP’s strategy to call at a frequency of 52% rather than 50%? How will IP change their strategy to exploit this slightly too loose calling strategy? Do you expect them to change not at all, to bluff slightly less, or to bluff dramatically less? You can see for yourself in the solution here.

This very small increase in OP’s calling frequency caused IP to stop bluffing altogether! This is because all those mixed strategies were extremely sensitive to OP’s response. Notice that none of the pure strategies have changed. TT remains most profitable as a check, because this was not an especially close decision at equilibrium.

If we turn OOP into a huge calling station who calls 100% of the time, that makes TT a value bet for IP, but 99 still plays best as a check.

Even when you choose to exploit an opponent’s mistakes, it’s useful to start with an idea of the baseline or GTO strategy. Once you understand which parts of that strategy depend most on your opponent’s response, you can make more informed and profitable decisions about how to deviate and exploit that response.

Adapting on Early Streets

When you anticipate an opponent making a mistake at a future node, the value of reaching that node with hands that will profit from that mistake increases, and you may be incentivized to play differently on early streets in hopes of profiting from that mistake later.

Suppose you had a read that a certain opponent called too often on the turn. Bluffing less on the turn would seem to be the obvious exploit, but what if they also folded too often on the river? In that case, you might actually be incentivized to bluff more often on the turn in anticipation of growing a pot you expect to steal later.

Similarly, if your opponent who bluffs too often on the river, you should factor that into your turn (and earlier street) decisions. Mostly this will mean calling more turn bets, anticipating extra value from bluff-catching rivers. But if your hand is an especially poor candidate for calling rivers, you are likely better off folding it immediately on the turn, even if it’s a hand that would be a profitable GTO call. The GTO strategy for such a hand would anticipate more checking and showing down on the river than you expect from this opponent.

These exploits can extend all the way back to pre-flop decisions. The more mistakes you anticipate an opponent making after the flop, the more incentive you have to get into pots with them in order to profit from those mistakes. There’s a big caveat here, though…

Multiway Pots

Before the flop, or any time there are multiple players with live hands, you are limited in your ability to exploit a specific opponent.

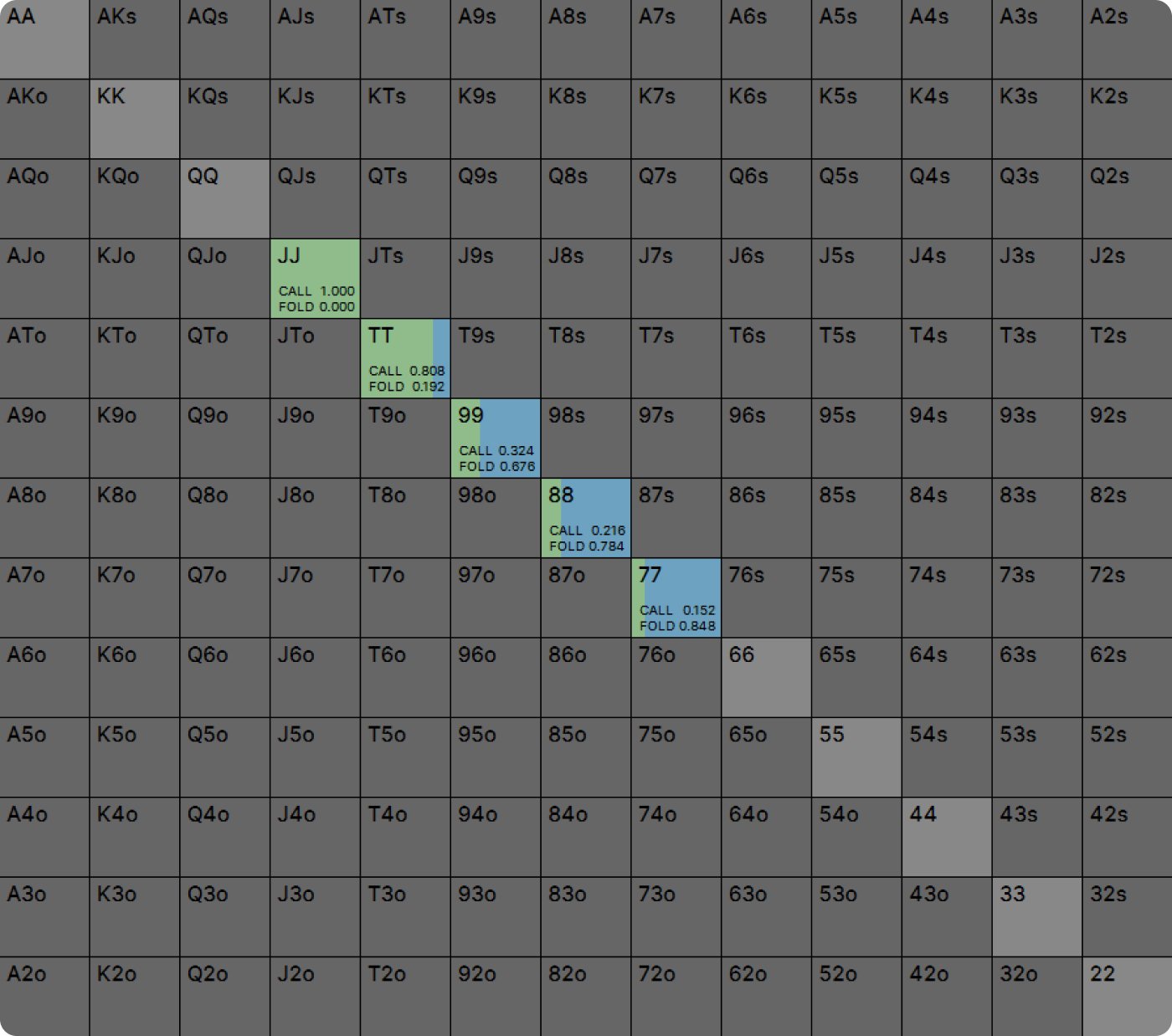

Suppose you know, before the flop, that the player in the BB is a nit who will fold their blind too often to a small raise. If you are UTG at a nine-handed table, you might be able to open very slightly wider than you otherwise would, but you still can’t get too out of line because of the seven other players who might call or three-bet you.

If the action folded to you on the BTN, you’d have a lot more leeway to open more hands, as the BB is now the primary constraint on your opening range. Even so, you’d be somewhat constrained by the threat of three-bets from the SB, especially if they were a savvy player who expected you to open wider against a tight BB.

A similar dynamic can occur after the flop. Suppose UTG opens, you call on the BTN, and the BB calls. UTG is an overly straightforward player who will reliably bet their strong hands and check their weak ones after the flop, but BB is a tough and savvy opponent whom you expect to be aware of UTG’s mistake and your likely adaptations to it. Should UTG check to you, you would want to bet somewhat more often than a GTO strategy would to take advantage of extra fold equity from UTG, but you should expect BB to call and check-raise you somewhat more often as well. As with the pre-flop example, both you and BB can adapt to exploit UTG’s mistake without becoming exploitable by one another. It is UTG who could exploit both of you, should they ever get wise and check some strong hands or check-raise some bluffs.

That latter case can best be thought of as a blend of GTO and exploitative dynamics, where both you and the SB are claiming a larger share of the pot by adapting to the BB’s mistake while trying to remain balanced against one another. This will entail you opening somewhat wider than you otherwise would, the SB calling and three-betting somewhat wider, and you calling or four-betting those three-bets with somewhat weaker hands than you otherwise would. A new equilibrium emerges, with the BB’s mistake enabling both you and the SB to play more hands without becoming exploitable against one another. The player who could profit from your deviations would be the BB, if they were to wake up to what was going on and increase their own calling, three-betting, and four-betting frequencies.

Author

Andrew Brokos

Andrew Brokos has been a professional poker player, coach, and author for over 15 years. He co-hosts the Thinking Poker Podcast and is the author of the Play Optimal Poker books, among others.