Counterintuitive Calls

Solver outputs such as those provided by GTO Wizard are models of no-limit hold ‘em, not a perfect blueprint for what you should actually do in a real poker situation. They are best thought of as instruments, tools with which you can study the game and better understand its underlying strategic principles.

When studying with solvers, it is essential to grasp not only what they recommend doing with specific hands but why they recommend those actions.

When studying with solvers, it is essential to grasp not only what they recommend doing with specific hands but why they recommend those actions. The EV of early street actions depends heavily on how you play future streets. Even if you could memorize and perfectly replicate a solver’s response to a 33% pot continuation bet on the flop, for instance, you wouldn’t capture the EV anticipated by the solver unless you knew when to fold, call, bluff, and value bet on later streets.

Capturing the predicted value of early street actions requires understanding what role each hand will play in your range on various runouts and facing various actions from your opponents. Sometimes, mostly with strong made hands and draws to strong made hands, those roles are easy to recognize and correct play in many future situations will be fairly intuitive.

In other cases, it will not be obvious why certain hands show up in certain ranges nor how to play them on later streets. When you encounter such results in a solver output, you should not simply shrug and take the solver’s word for it. Rather, you should investigate what the solver recommends for later streets until you understand where the value of the counterintuitive action comes from and are confident you can handle those tricky spots. Otherwise, your future mistakes may well cost you more EV than the recommended early street action is predicted to earn you in theory.

This lesson will demonstrate how to conduct such investigations for yourself, as well as a few common heuristics that should help you make sense (and profit!) of some of the more counterintuitive calls solvers recommend in the face of small continuation bets.

A Portfolio of Value

Sometimes it is obvious where a hand’s value comes from. When you call a continuation bet with top pair, most of your value comes from showing down the best hand and perhaps even picking off a bluff or making a value bet of your own on later streets. When you call with a flush draw, most of your value comes from making the flush and ideally winning another bet or two once you do.

Even with these hands, though, it is not all so straightforward. Sometimes you need to fold that top pair to heavy action, or even turn it into a bluff. Sometimes you’re supposed to bluff the flush draw when it misses, other times you aren’t. If you don’t get those decisions right, you won’t get all the value of these calls, but you will still get most of it. These calls are easy to find because the bulk of their value comes from one easily recognized source.

Of course, top pair and flush draws never fold, but some calls are less obvious. K9 with a backdoor flush draw never folds, even when the diamond is just a 9. 53 never folds, even without a backdoor flush draw. Are you really supposed to call here just to chase a gutshot or a backdoor draw?

No. The solver does not recommend calling just to chase those hands, though that is where a big chunk of the value comes from. These hands also derive value from improving to a pair (even 53 has a shot at winning by turning a pair!) and from bluffing.

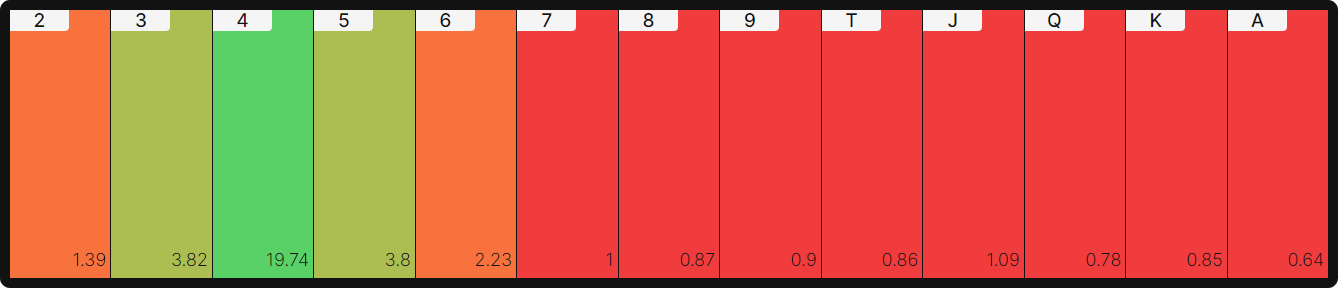

Improving to a straight or flush is worth a lot, but it happens rarely. Bluffing or improving to a pair is worth a good deal less, but it happens more often. None of these alone would warrant a call, but they each contribute enough scraps of EV that calling with 53 no diamond should be worth about 1bb more than folding… if you know what to do with it on later streets. One method to visualize this “portfolio of value” is to chart BB’s EV of 5♥3♥ by turn card. The expected value of hitting our gutshot makes up about 57% of our expected value on the turn. Keep in mind, however, that these turn values include the EV of potentially rivering a straight.

It’s OK to Fold

Your opponent’s actions are a significant factor in determining what your hand is worth and what you should do with it.

It’s not just the board that determines how you play later streets. Your opponent’s actions are a significant factor in determining what your hand is worth and what you should do with it.

When you call the flop, it helps to keep in mind why you called, what you’re hoping for. With the 53, you’re hoping for a turn that improves your hand or a check from your opponent, indicating that their own hand is probably not great either. If you don’t get either of those things, you’re probably just going to fold, and that’s fine.

You didn’t call the flop because you had a great hand or expected to win the pot. You called because you were getting odds of 4:1 and still had some longshots that were worth chasing.

When the turn doesn’t help you, a lot of your longshot potential goes out the window. The likelihood of filling your gutshot is cut in half. If your opponent bets again, they probably won’t offer such a good price, and even if they do, it wouldn’t be good enough, as your hand is worth less than it was on the flop.

You aren’t obliged to keep fighting for the pot. You probably shouldn’t. When you call getting 4:1 odds, it’s correct to lose most of the time. If you don’t cut your losses on bad runouts, they will quickly overwhelm the value of the flop call.

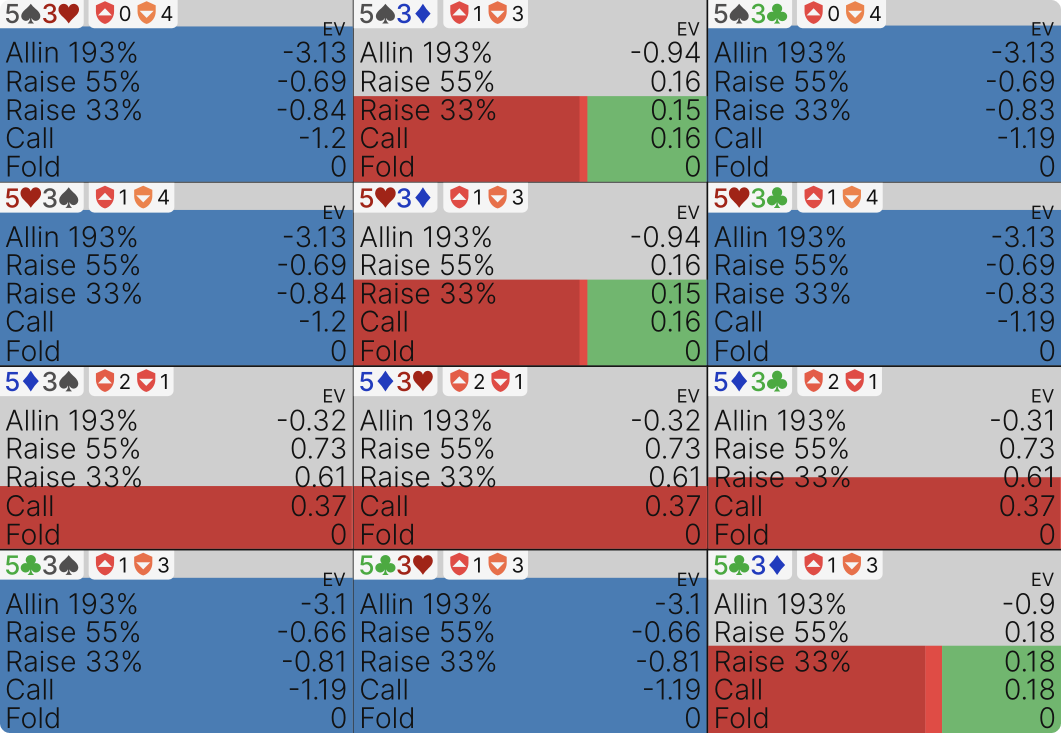

If the turn is the 8♦, for example, you should just check 53 no diamond, and fold if your opponent bets. GTO Wizard recommends folding even to a 33% pot bet.

Note that 53 with a diamond does not fold to this small bet. Especially with the 5♦, it’s a good candidate for bluffing. It’s even a candidate for donk betting this turn, though that’s a rarely used line. If you fail to find this bluff with 5♦ 3, you will not realize all the equity of your flop call.

Bluffing the River

Checking with the intention of folding does not mean “giving up” because it is far from a guarantee your opponent will bet. GTO Wizard has the BTN checking this turn 56% of the time. That means if your opponent does bet, that’s a significant new piece of information that strengthens their range and makes your own weak hands less appealing.

Checking with the intention of folding does not mean “giving up”.

If your opponent does not bet the turn, that’s your cue to think about bluffing. Even then, these are not especially high-value bluffs. On a Q♥ river, 53 without a diamond is indifferent to bluffing, and 53 with a diamond is a barely profitable bluff.

That’s because these are not your only bluffing candidates. That K♦ 9 that was also a counterintuitive flop call is a more solidly profitable bluff, as it blocks more flushes and the rivered straight.

Getting There

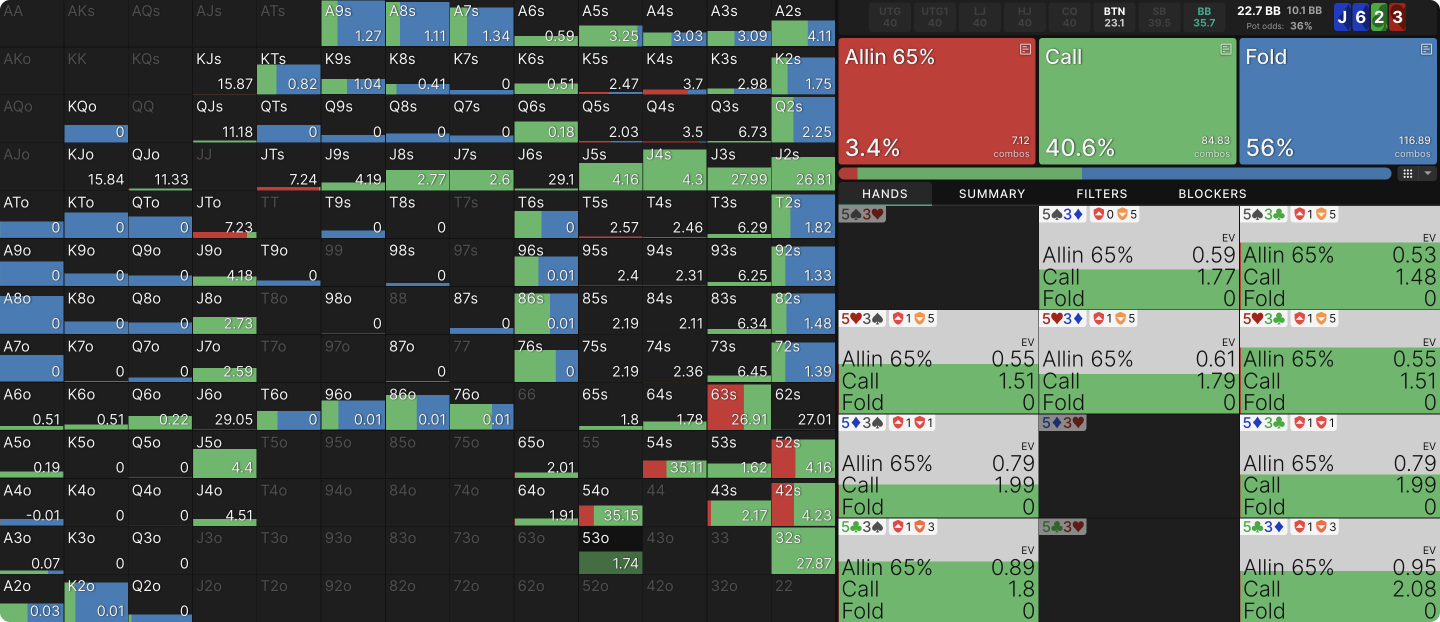

Every once in a while, the stars align: your opponent checks behind the turn, and you drill that gutshot on the river. The final board is J♦ 6♦ 2♣ 8♦ 4♥. There’s 10.1bb in pot and 35.7 in the stacks. What’s your play with 53?

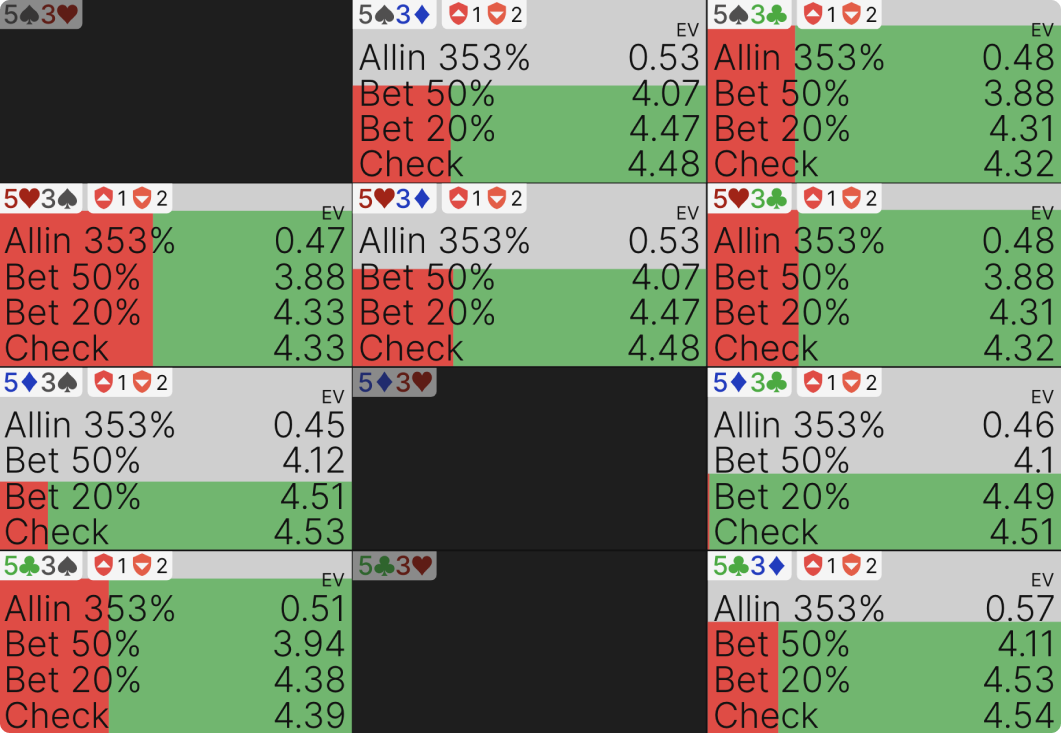

You’ve got some options. GTO Wizard mixes between checking, betting small (hoping to induce a raise), and even shoving for 353% of the pot.

It’s not enough to make the straight; realizing the full EV of the flop call requires getting paid big when you do. If you check or block bet, it should be the intention of shoving over a bet or raise, not just calling for fear your opponent has a flush. It’s not worth chasing if you don’t appreciate the value of your hand when you hit it.

Making a Pair

Turning third pair may not seem like much, but it’s actually a huge boon for the EV of your 53. Facing the continuation bet on the flop, 53 without a diamond was worth about 1bb. Seeing the 3♥ turn quadruples its value to more than 4bb.

The gutshot is a big contributing factor; 86 without a diamond is worth barely 2bb despite being a higher pair.

A lot of the value of the flop call is wrapped up in the runouts where you make a weak pair.

So, a lot of the value of the flop call is wrapped up in the runouts where you make a weak pair. But weak pairs are some of the toughest hands to play, so realizing that equity can be tricky.

For instance: what do you do if you check the J♦ 6♦ 2♣ 3♥ board only to face a 125% pot bet, which GTO Wizard would have the BTN make with 23% of their range?

53 is a pure call, with more value than middle pair, which is mostly indifferent between calling and folding. Before the river, a weak pair with a draw to something nutty is typically a better bluff-catcher than stronger pairs without significant redraws.

How about if the action checks through on an 8h turn and then you river the 3♥?

You should start with a check or a 10% pot block-bet, as your hand has showdown value. If you face a bet or raise, however, you should turn your pair into a bluff and shove. Here’s the response to an 84% pot bet, BTN’s most commonly used size.

What makes 53 so appealing as a bluff? For one thing, it loses most of its showdown value once the BTN bets. Calling would be worth about a tenth of a big blind. More importantly, it blocks some important hands: the nuts, but also some sets and stray two-pairs. BTN’s turn check removes most nutty hands from their range. Their best shot at holding something nutty now is if they rivered it. Because your hand blocks so many of those rivered nuts, it’s a nice bluffing candidate.

Conclusion

There’s no way to study every possible turn and river scenario that could stem from every marginal flop call. We’ve barely scratched the surface of one scenario here. But what you can do – what this piece demonstrates how to do – is consider how your hand will play in a few important scenarios.

- What conditions will make your hand good for bluffing if you miss?

- How much value can you get if you hit?

- How should you manage the tricky spots where you improve to something marginal?

Studying how a solver handles these spots can help you develop heuristics that will be useful in many other situations. Armed with those heuristics, you’ll learn how to recognize these counterintuitive calls “in the wild”, how to realize enough value to make them worthwhile, and how to avoid the blunders that could undermine their profitability.

Author

Andrew Brokos

Andrew Brokos has been a professional poker player, coach, and author for over 15 years. He co-hosts the Thinking Poker Podcast and is the author of the Play Optimal Poker books, among others.