ICM Strategy: Playing IP Against the Chip Leader on the Final Table

The good news is you’ve made the final table (FT). Better yet, you’ve made it with a big stack, good for second place out of eight players remaining.

The bad news is the chip leader is on your left, and they cover you by a lot. This is their table, not yours, so despite your relatively big stack, you’ve got to sit tight. You’re handcuffed, mostly folding and waiting for other players to get eliminated while you watch the chip leader hoover up the blinds you’d really like to be stealing yourself.

Finally, you get your opportunity. You’re in late position, and your nemesis is in the SB, where they’re least likely to menace you. You open for a raise, eager to steal the blinds at last… and the chip leader calls!

Now what? You’re pretty sure they don’t have a great hand or they would have 3-bet. That makes it tempting to keep up the aggression after the flop. But you’re rightly wary of a big confrontation that could take you from second place to out in eighth in a single hand. How often should you continuation bet? On which boards? What if the SB preemptively bets into you?

This article will equip you with the tools to think through such tricky, high-stakes decisions. As always, however, to understand postflop strategy, we’ve got to start at the beginning, with what happens before the flop.

The Scenario

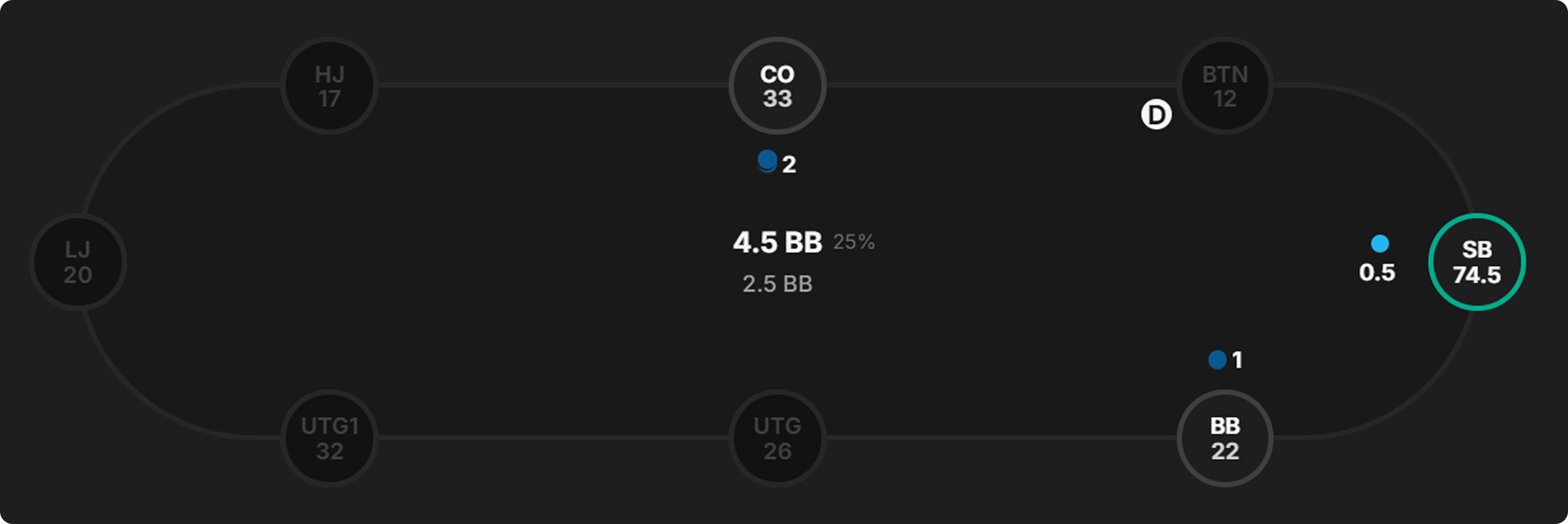

The examples we investigate will come from an 8-handed FT with an average stack of 30bb. The CO, who is in second place with a 35bb stack, opens for a min-raise and is called by the SB, who, with 75bb, enjoys a big lead over the rest of the table.

All positions and their stacks are listed in the chart below:

Though not as bad as getting 3-bet, this is an extremely dangerous spot for CO, who has a risk premium of 17.8% against SB! (For comparison, SB’s risk premium against CO is 6.6%). Investigating this extreme example will make it easier to recognize the strategic adjustments a solver would make in the CO’s shoes to navigate this dangerous scenario. The same general considerations will apply when fewer players remain or when the covered player has fewer chips, but the magnitude of their effects will be lessened.

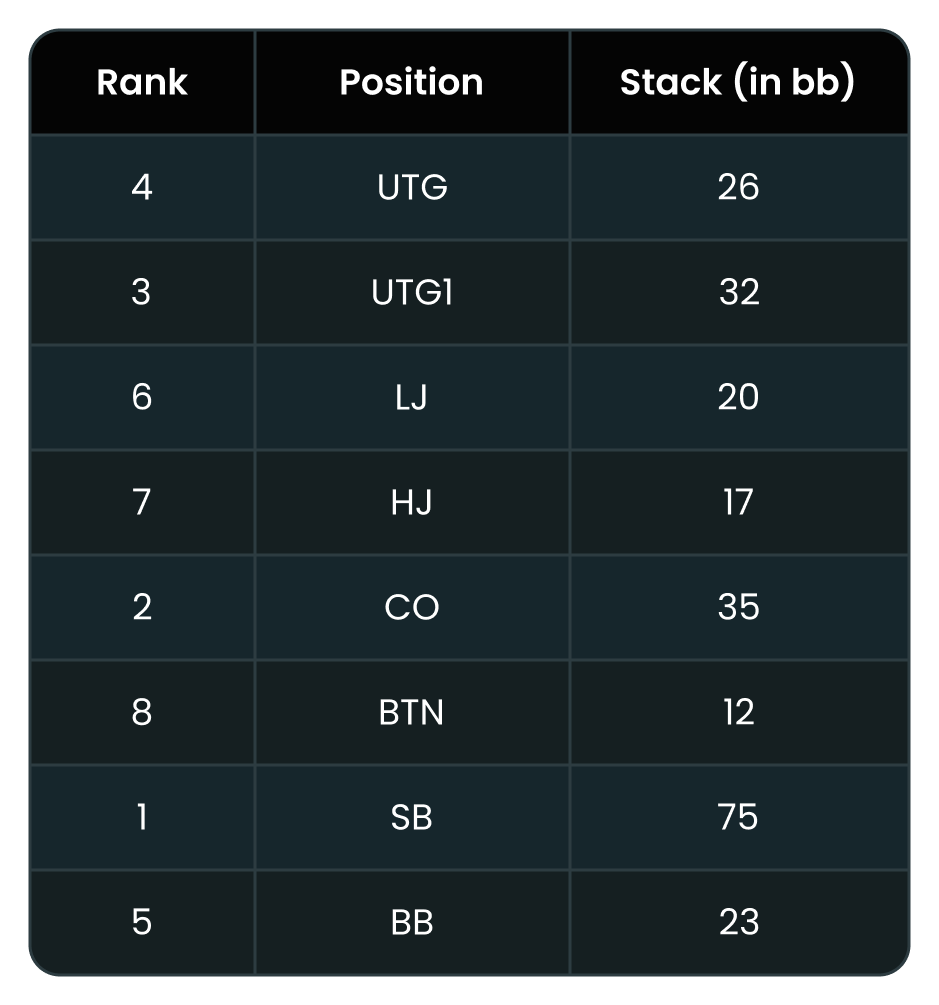

CO opens 26% of hands, a far cry from the 37% they would open in a 30bb Chip EV simulation. Even with the chip leader in the SB, where they can do the least damage, the threat of them contesting the pot dramatically constrains CO’s ability to attack the player(s) they cover in the blinds. Their opening range is heavy on Broadway cards, especially Ace-x, which block the continuing ranges of the players behind them.

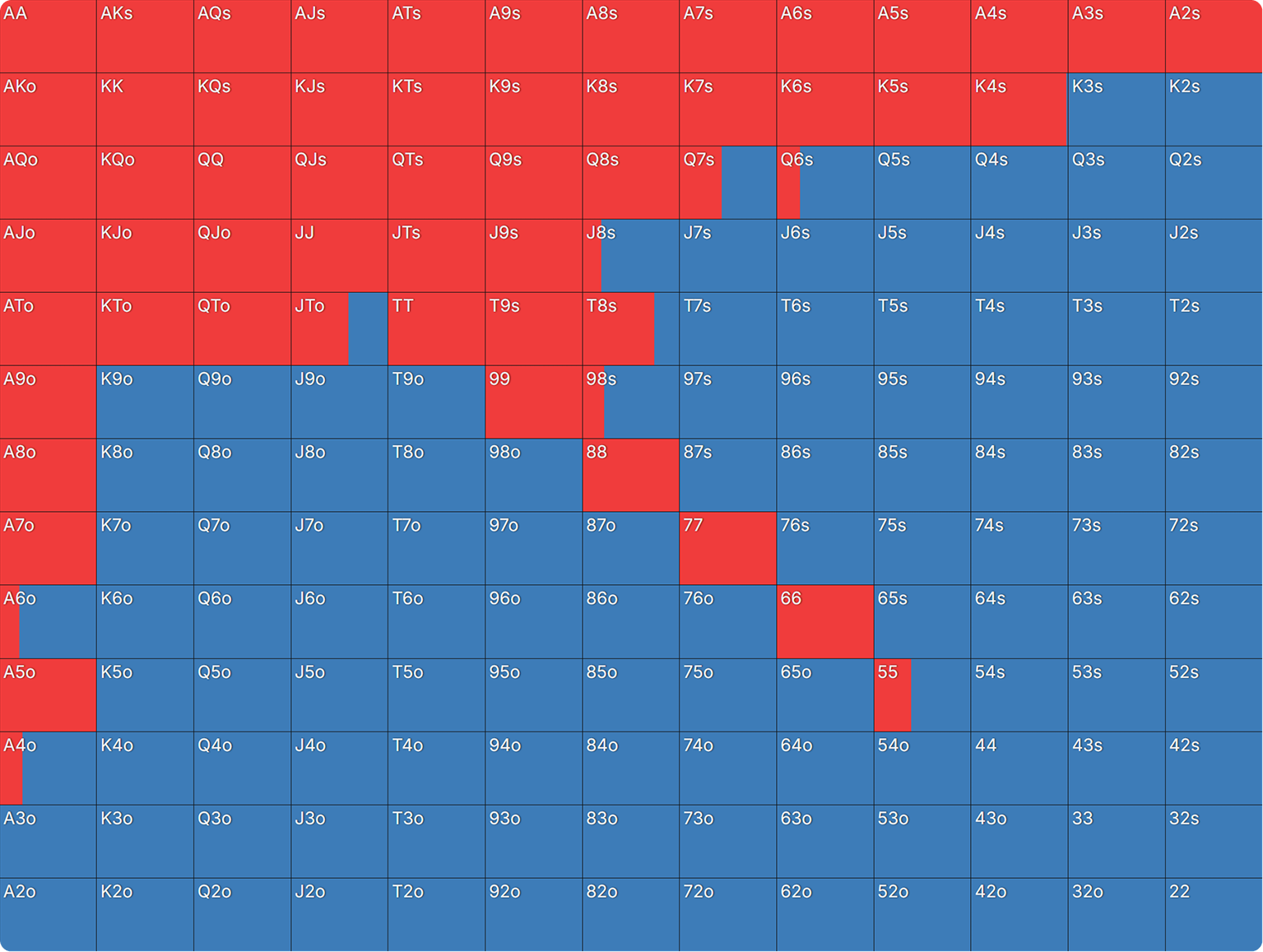

SB’s calling range also contains a fair bit of Ace-x (remember, each box in the grid represents 12 combos for an offsuit hand but only 4 for a suited hand), but not as disproportionately much as CO’s. Instead, SB’s range contains more speculative hands like small pairs and suited connectors:

These hands can expect to over-realize their equity after the flop thanks to CO’s risk premium, which should lead to more free cards, more bluff opportunities, and more cheap showdowns when SB wants them.

Flop Strategy

Armed with these descriptions of each player’s range, it is fairly simple to predict which flops will favor the CO and which the SB. CO has the most equity on Broadway-heavy flops, especially those with an Ace. SB does better on lower, coordinated flops:

CO continuation bets quite often, in general, relative to when they are called by a covering stack in position (IP). Position makes it considerably safer to grow the pot on the flop, as they will have more control over whether it continues to grow on future streets. They also get more folds when the covering stack is out of position (OOP), which is an enormous boon when playing with a high risk premium.

SB leads more often on flops where they have more equity, of course, but the correspondence is not perfect. They lead about half their range on A♦9♦4♦, a higher frequency than on Q♥T♦9♦ or Q♥7♣3♠, despite the fact that they have more equity on those other flops!

The correspondence is not perfect for CO, either. They bet only half their range on A♠T♥T♦ despite flopping a whopping 65% equity. They bet more often 7♠2♥2♦, where they have just 55% equity.

In CO’s case, there is a complication in that SB has already acted by the time they have the opportunity to bet. When CO flops less equity, SB is incentivized to bet their strong hands, meaning they have less equity when they check. If we were to force SB to check all these flops, we would see CO’s betting frequency align more closely with their equity, but the correspondence still would not be perfect.

When playing under a hefty risk premium, the optimal poker strategy is less about investing chips with an equity advantage and more about protecting what you already have.

Specifically, there are two things CO (and, to a lesser degree, SB) focuses on protecting:

- Their equity in the pot.

- The tournament equity still in their stack.

These two objectives are in tension with one another. Protecting their equity in the pot often requires betting to avoid getting drawn out on and/or calling bets to avoid getting bluffed, both of which entail putting more of their stack at risk.

These objectives determine when CO has the most incentive to bet. They bet most often when:

- They have a lot of equity to protect.

- A significant amount of that equity is vulnerable to free cards.

- They have enough nutty hands in their range that SB cannot raise with impunity.

With these principles in mind, let’s take a closer look at CO’s more surprising flop strategies.

Static Flops

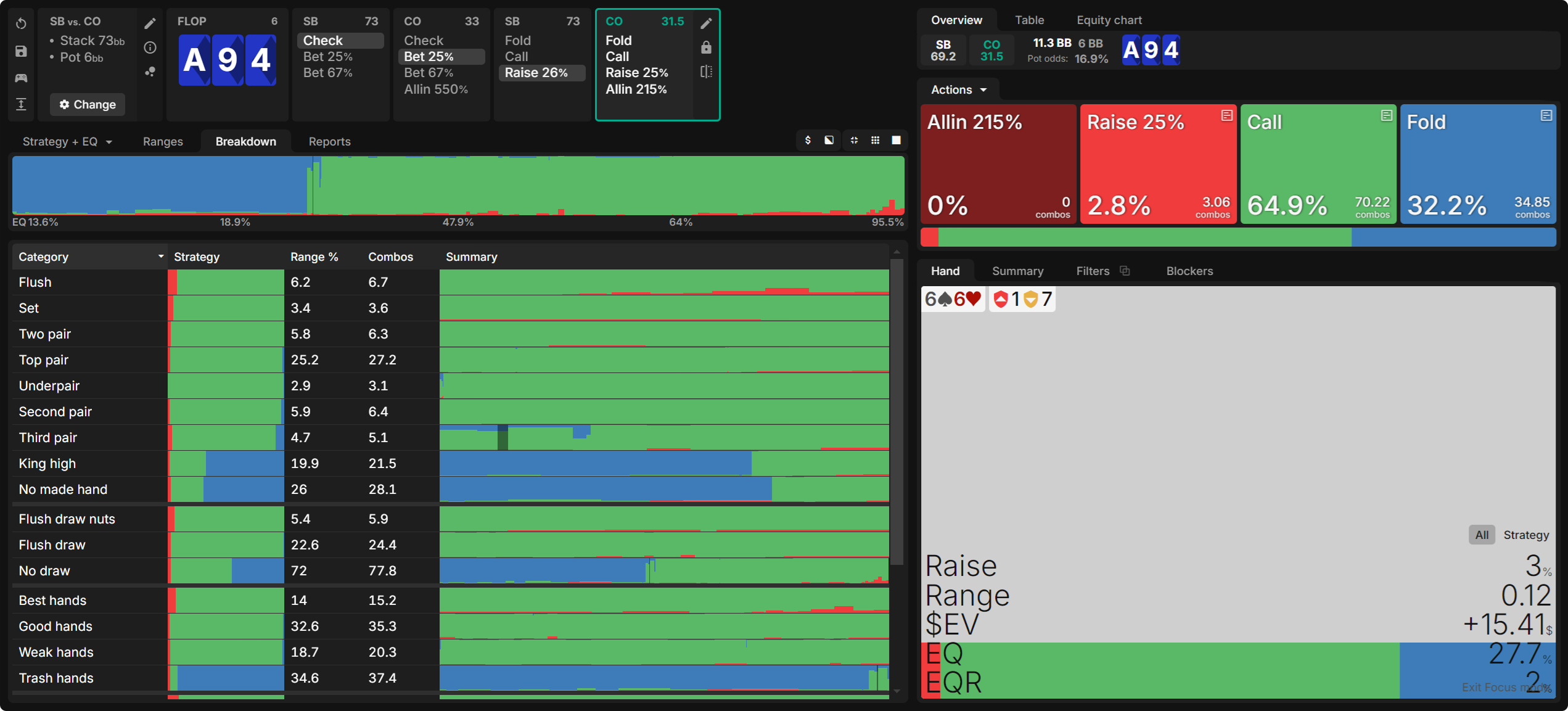

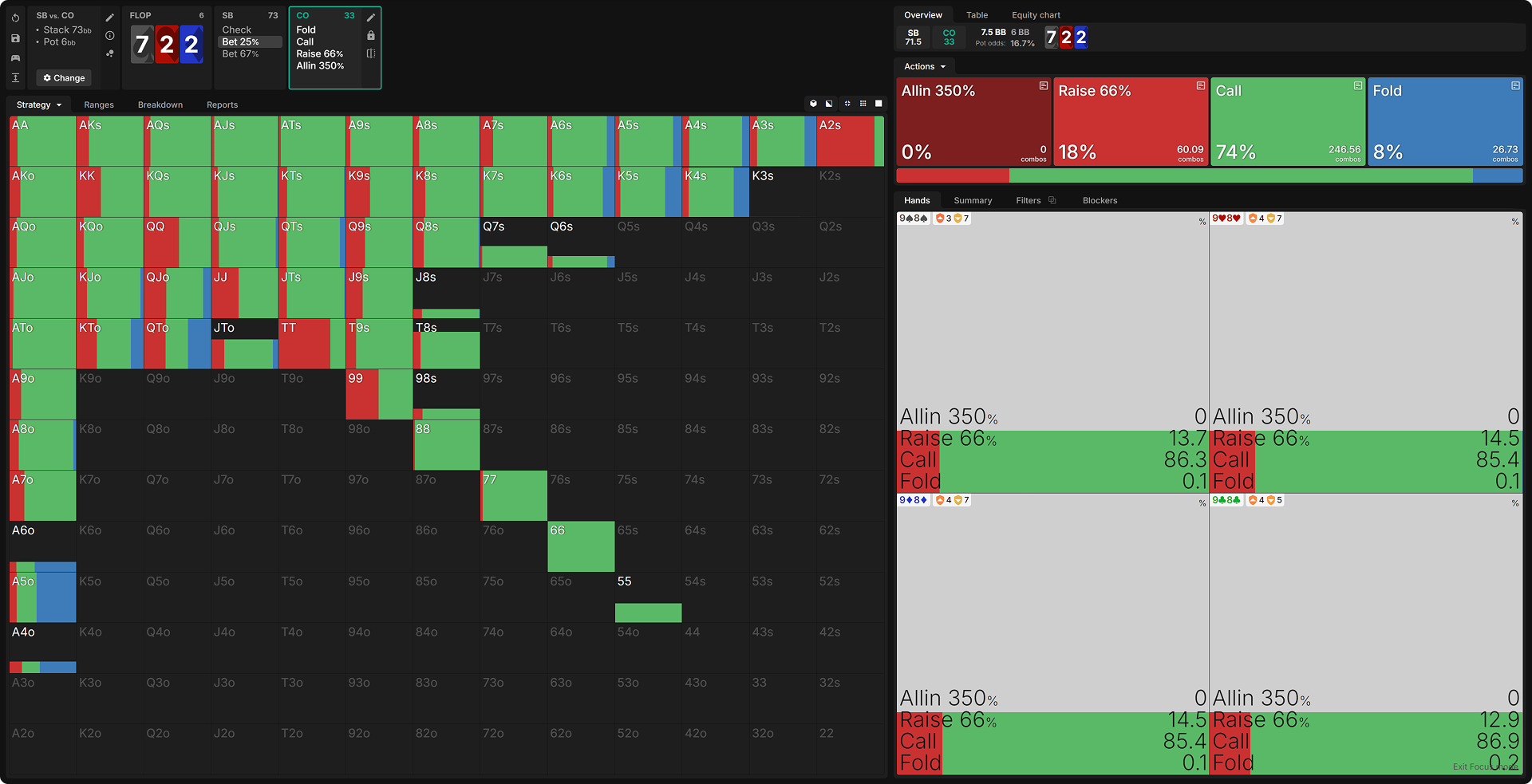

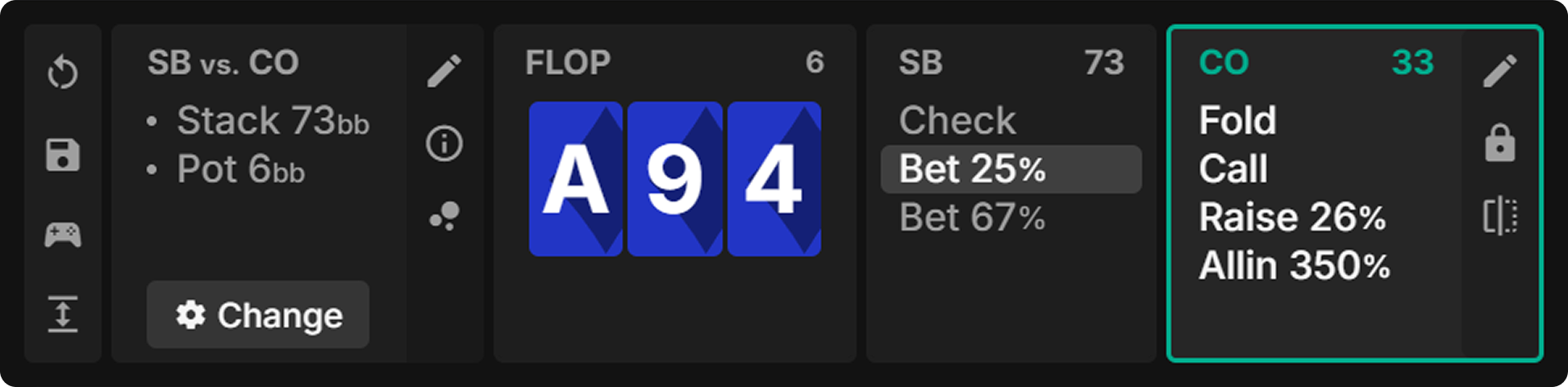

A94m

CO flops 56.7% equity on A♦9♦4♦ and has 60.6% equity against SB’s checking range. Yet, they bet only 37% of hands, less than on other boards where they have less equity.

A94m is among the most static flops, which makes protection less important. When CO flops top pair, they don’t have to worry about SB turning a larger one. A fourth diamond could be worrisome, but far more non-diamonds remain in the deck. SB has a diamond that they probably aren’t folding anyway. So, CO can’t really protect against that. The Ace and 4 make a few gutshots possible, but most of them aren’t in SB’s range. Sets and flushes, of course, are harder yet to draw out on.

Indeed, most of CO’s checks come from the middle of their range. A♠2♠ is a perfect example: it has 70% equity but little incentive to bet. SB mostly won’t fold hands with significant equity anyway, so CO would prefer not to risk opening themselves up to a bluff or contesting a large pot against stronger hands that will have them drawing nearly dead.

We can see from CO’s response to a small raise that this range is constructed to avoid tough decisions. With just a few squirrely exceptions in the middle, their strategy can be summarized as: Call if you have a pair or better or a flush draw, fold otherwise.

By betting hands with clear incentives, CO avoids tough decisions when raised.

Things get a little trickier if CO checks back the flop and then faces a large turn-bet. On blank turns (which is most turns, on a static flop), they face a lot of tough decisions and sometimes fold hands as strong as top pair with a modest kicker.

Even so, SB makes this bet only 16% of the time. CO flops enough equity that, even though they put their strongest hands disproportionately into their betting range, they retain a lot of strength in their checking range. In fact, they have 61.6% equity on a 6♠ turn, which is slightly more than they had before checking the flop.

Why? Because they also put their weakest hands disproportionately into their betting range. Checking did not weaken their range, although it did cap it. Thus, they retain a lot of equity on the turn but have more difficulty defending it on the rare occasions that they face large bets. But the flop check is decidedly not a green light for the chip leader to start blasting the turn.

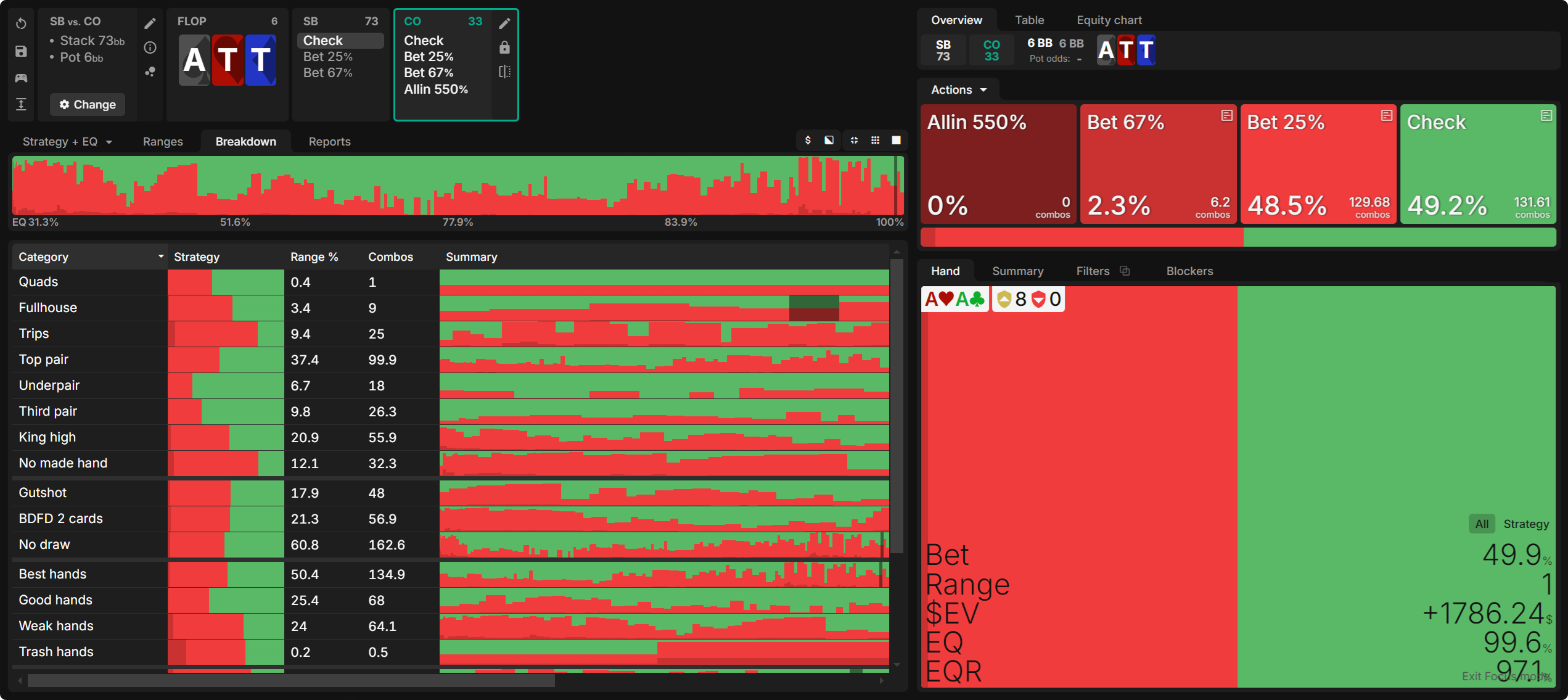

ATTr

A♠T♥T♦ is a similarly static flop with a similarly polar betting strategy. It offers SB more straight draws but no flush draws. The straight draws on this board also being in CO’s range makes them less vulnerable to bluffs on Broadway turns. It also helps that they can turn full houses on these cards.

Dynamic Flops

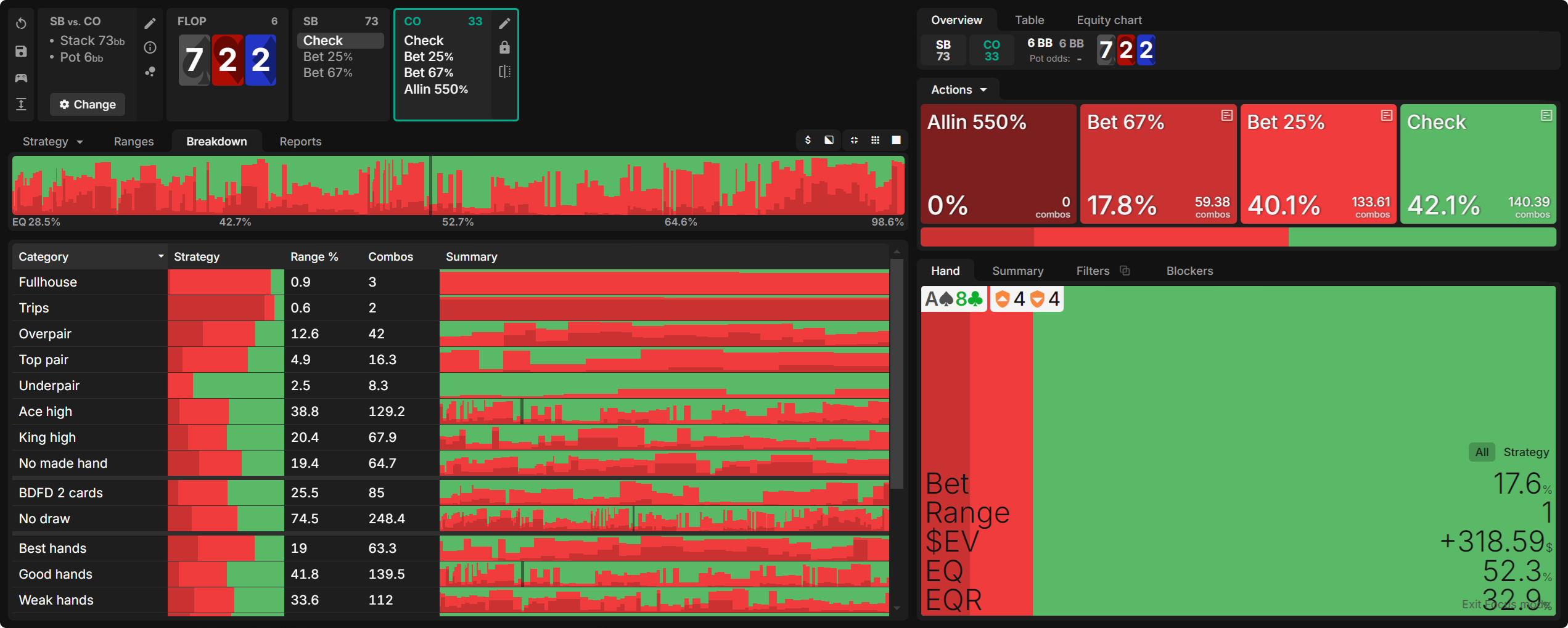

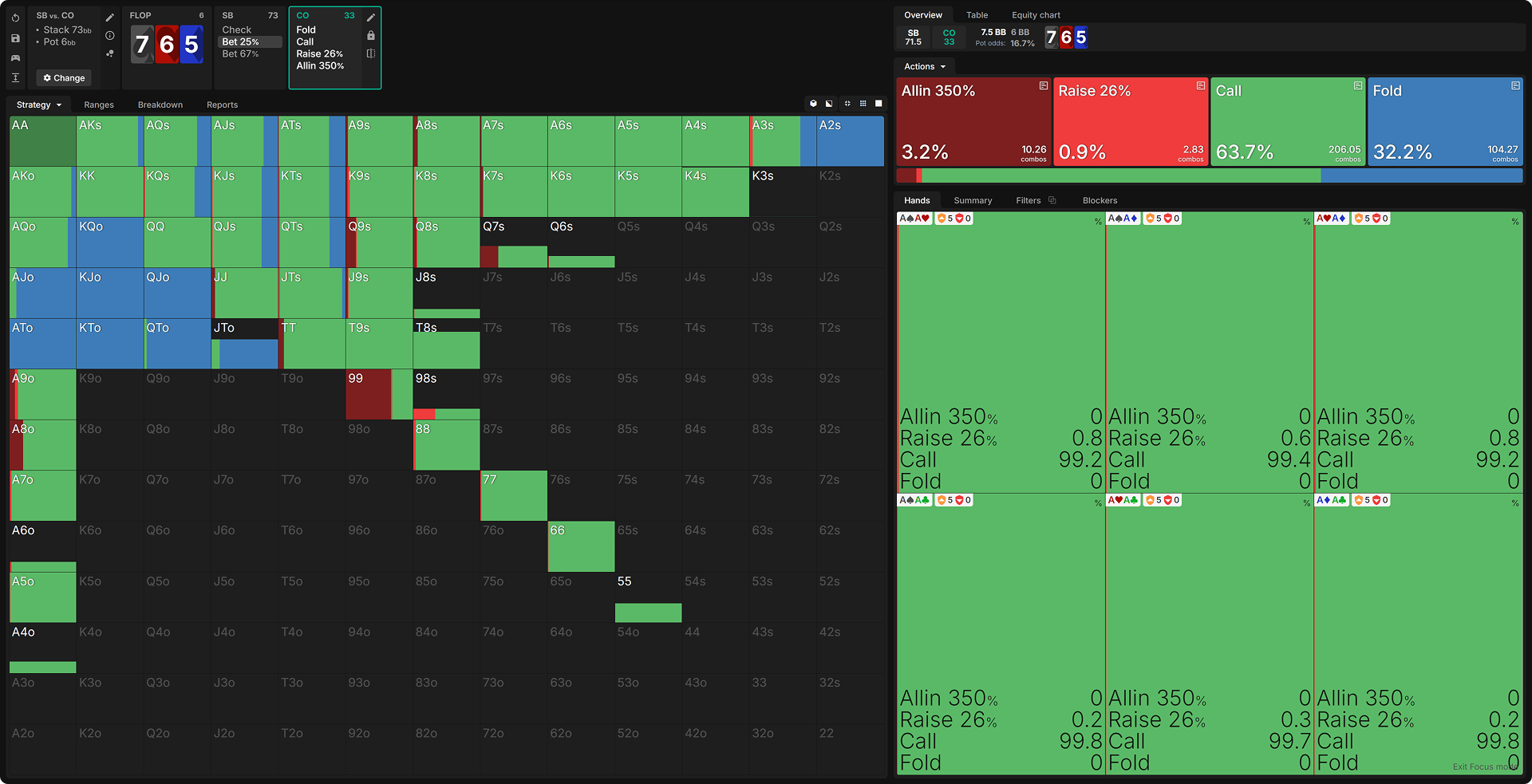

722r

Despite the lack of straight or flush draws, 722r is actually an extremely dynamic flop. Most hands in both players’ ranges will be unpaired, making it easy to draw out on medium pairs and higher unpaired hands. CO has more of these currently-ahead-but-vulnerable-to-free-card hands and, consequently, more incentive to bet than on ATTr despite having less equity.

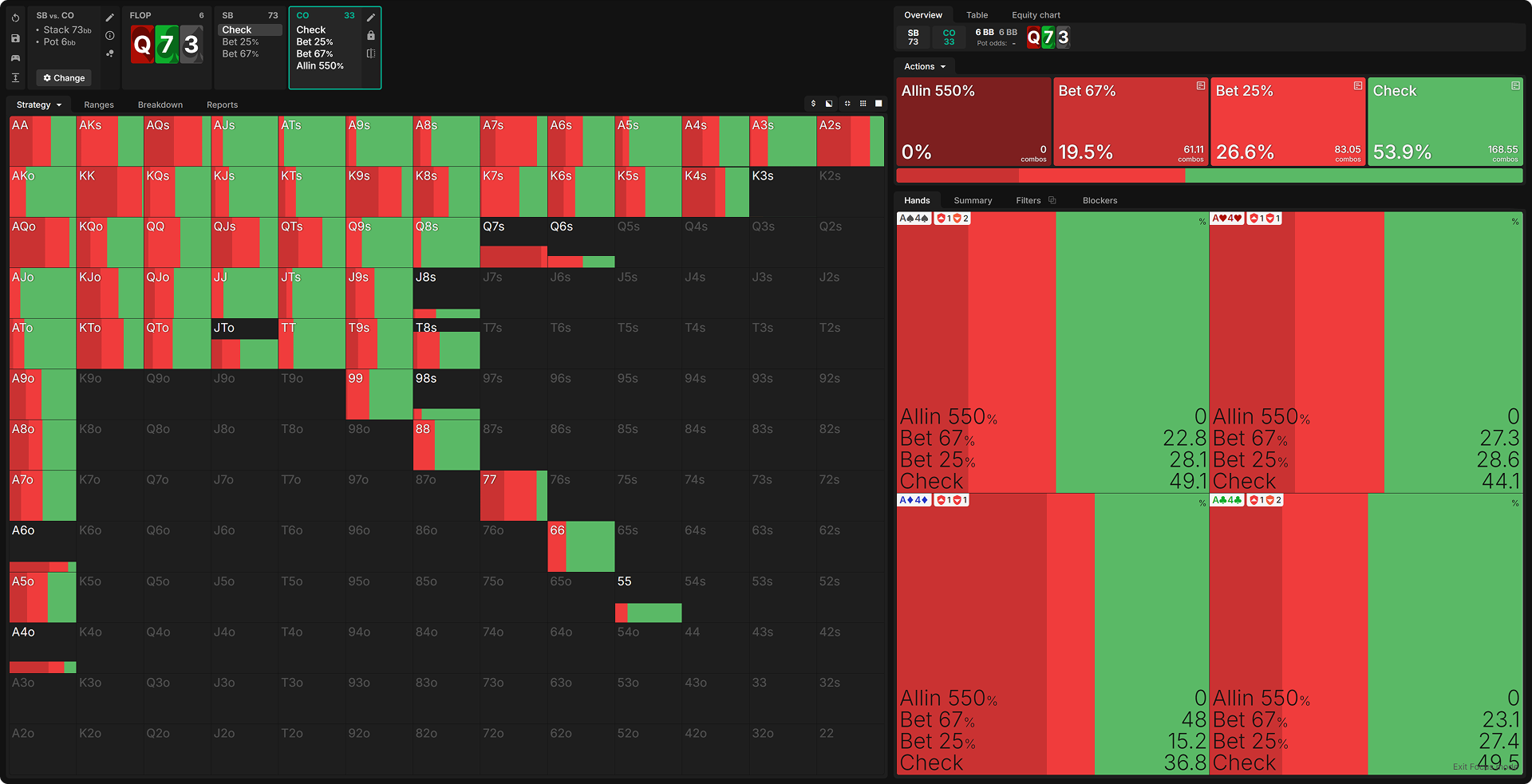

Q73r

Q73r is less dynamic than 722r, and CO flops less equity than on ATTr. This results in less continuation betting than on either, with an emphasis on strong-but-vulnerable hands like AQ and KK.

This preference for betting strong-but-vulnerable hands will be familiar to regular blog readers, as it is a staple of many scenarios. What makes this one unique is the threshold for what counts as vulnerable. In other circumstances, KK would be robust enough to consider slow-playing. With such a high risk premium, however, CO shows a stronger preference for locking up the equity they already have in the pot over trying to induce further action with a deceptive check.

Responding to Donk-Bets

Dynamic flops offer more incentive for CO to raise, just as they do to bet.

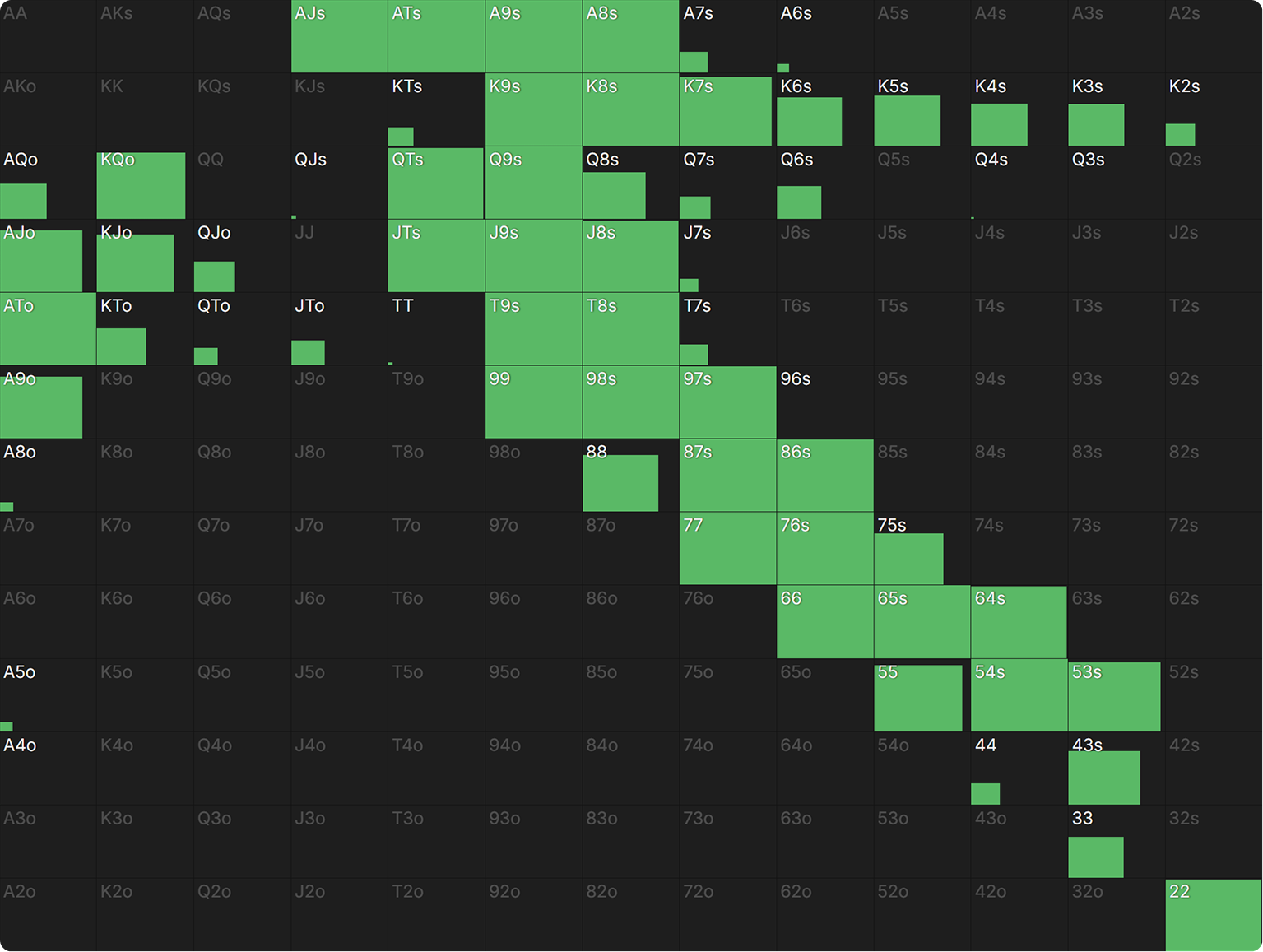

Lacking the nuts advantage, SB is judicious about donk-betting on 722r, betting 25% pot (their more commonly used size) with just 11.4% of hands. Nevertheless, CO raises aggressively, with a clear preference for strong but vulnerable pairs. Even their frequency of raising these pairs correlates with how strong and vulnerable they are: 88 is not strong enough to raise, AA is not vulnerable enough, and 99 through QQ are the most frequent raises:

A94m

In contrast, CO never raises even a small donk-bet on the more static A94m flop. Few hands are strong enough to raise for value, and those that are have little need for protection.

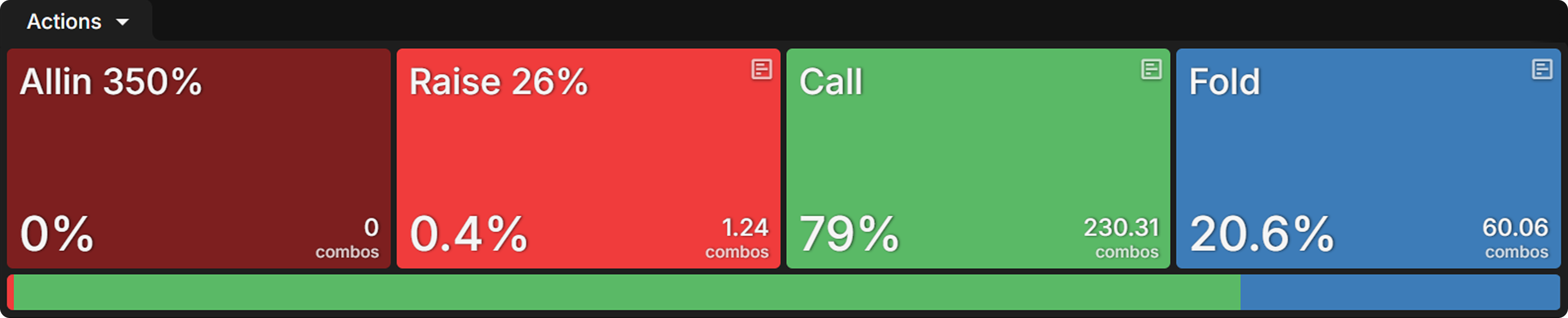

765r

Raising is undesirable for a different reason on 765r: CO has so little equity and so few strong hands on this board that they do not want to grow the pot (this is also why they have no bets on this flop, and why SB leads their entire range). Even getting all-in with top set against an open-ended straight draw presents a risk that borders on unacceptable.

Once again, the one hand with the most incentive to raise is both strong (the gutshot straight draw is important both for the blockers and for the extra outs when behind) and capable of folding out substantial amounts of live equity.

Conclusion

Contesting a pot against a covering stack at the final table is dangerous, and you should proceed with caution even when you have the advantage of position. Position is a considerable advantage, however, and you can leverage it to protect your equity and reduce your risk if you choose your spots with care.

The impetus for betting is more about folding your opponent’s equity than growing the pot. Even on flops that are very good for you, you should mostly be asking, “How do I protect my equity in this pot without jeopardizing the rest of my stack?” rather than “How do I get more money into a pot I’m favored to win?”

This means you should mostly bet and raise your strongest hands, especially when those hands are vulnerable to getting drawn out on. That’s a common theme even in Chip EV sims, but it takes on added importance in ICM sims, where the amount of risk of losing the pot you are willing to accept should be lower. ICM incentivizes you to protect what you already have, and that includes equity in pots that have not yet been pushed to you. When you do decline to raise very strong hands, it should generally be because you’re waiting for a safe runout rather than because you’re trying to induce further action.

Risk mitigation is the name of the game when it comes to FT strategy. That’s especially true when you’re contesting a pot with a player who covers you.

Position gives you a bit of leeway to protect your equity, however, and that is its own kind of risk mitigation. Now that you have a better idea of how to balance the risks and rewards of c-betting into a covering stack, you can take advantage of these opportunities to deny equity and pick up a few extra, critical pots!

Author

Andrew Brokos

Andrew Brokos has been a professional poker player, coach, and author for over 15 years. He co-hosts the Thinking Poker Podcast and is the author of the Play Optimal Poker books, among others.

Wizards, you don’t want to miss out on ‘Daily Dose of GTO,’ it’s the most valuable freeroll of the year!

We Are Hiring

We are looking for remarkable individuals to join us in our quest to build the next-generation poker training ecosystem. If you are passionate, dedicated, and driven to excel, we want to hear from you. Join us in redefining how poker is being studied.