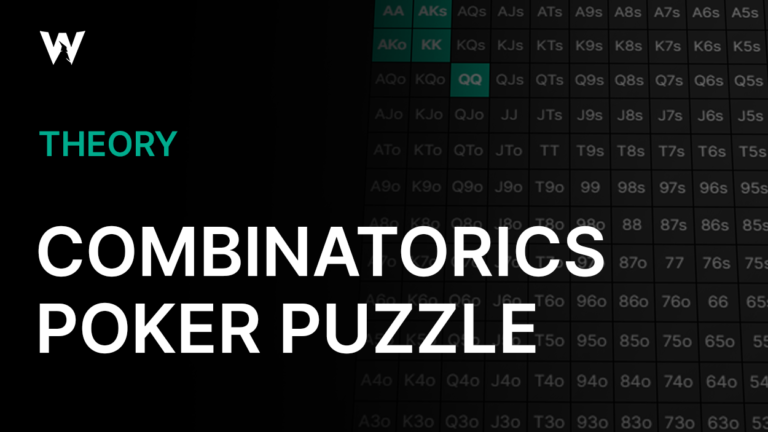

Probe Betting

As far as rules of thumb go in poker, “check to the raiser” is a pretty good one. The aggressor on the previous street generally has the more polar range and so more incentive to bet, while players who just called the previous street have mostly medium-strength hands and less incentive to grow the pot.

But what happens when the previous aggressor declines to bet? As with most things in poker, “it depends”. This article will look specifically at playing the turn as a BB caller against a LJ raiser who declined to continuation bet the flop in a 100bb cash game, but the general principles discussed here will apply in any situation where a player who had been the aggressor stops betting.

Range Dynamics

What does it mean that the preflop raiser chose not to bet the flop?

The first thing to determine is: What does it mean that the preflop raiser chose not to bet the flop? This depends on the answer to another question: How much did the flop favor the preflop raiser? An in-position raiser has a much stronger preflop range than a BB caller, and they carry this range advantage forward to the flop. In other words, LJ should enjoy a significant range advantage on most flops, though some are better than others. This is why they can continuation bet at a high frequency.

On more favorable flops, a check typically indicates not a weak hand but a medium hand that did not stand to benefit terribly much from betting.

When they do not bet the flop, the composition of their checking range depends heavily on how good the flop was for them. On more favorable flops, a check typically indicates not a weak hand but a medium hand that did not stand to benefit terribly much from betting. In this case, the BB will enjoy a nuts advantage but not an equity advantage on the average turn, which means they will bet at a low frequency for a large size. On less favorable flops, the preflop raiser cannot expect to bet their entire range profitably and thus are forced to check some of their weak hands. In these cases, the BB is more likely to enjoy both an equity and nuts advantage on the turn and so to bet at a higher frequency, though this depends on how much the turn card changes that dynamic.

Favorable Flops

On many flops, the preflop raiser’s stronger range buys them a profitable bet with any two cards against a BB caller. The only reason for them not to bet, then, is if they expect to make at least as much by checking, through some combination of taking their hand to showdown or bluffing on later streets.

On some very favorable flops, the LJ raiser does not check at all. These boards do little to help the BB and are very dynamic, incentivizing LJ to bet even their medium–strength hands for some combination of value and protection. Paired and tripped boards like 333 and QQ5 are good examples.

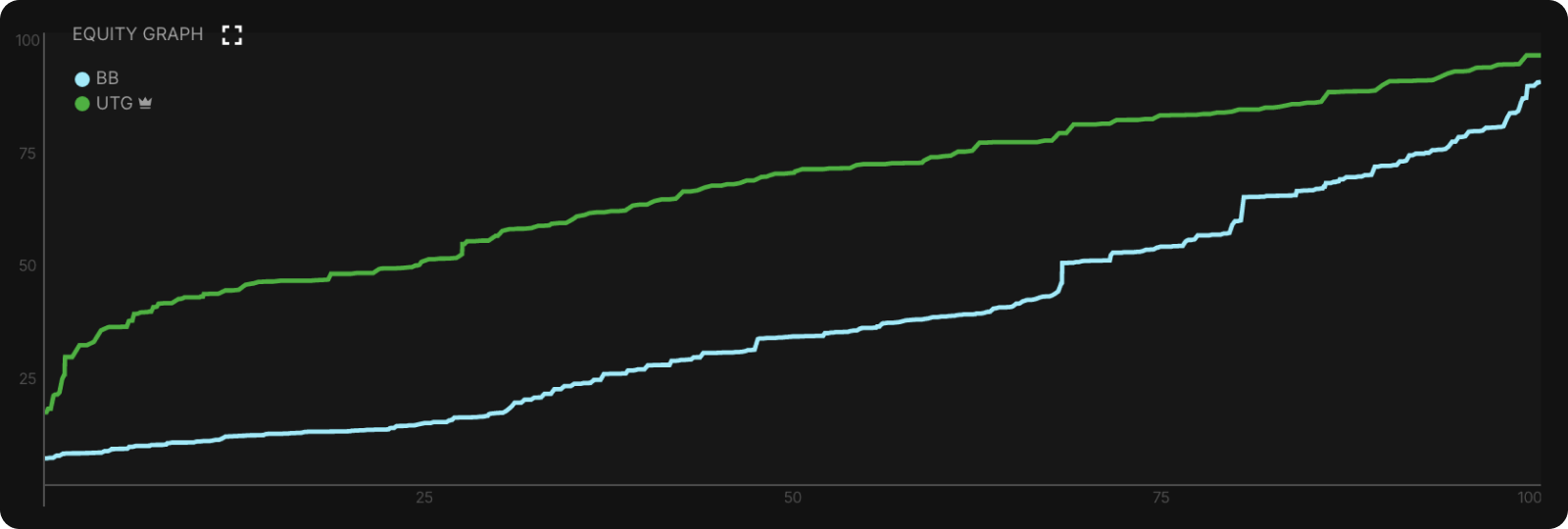

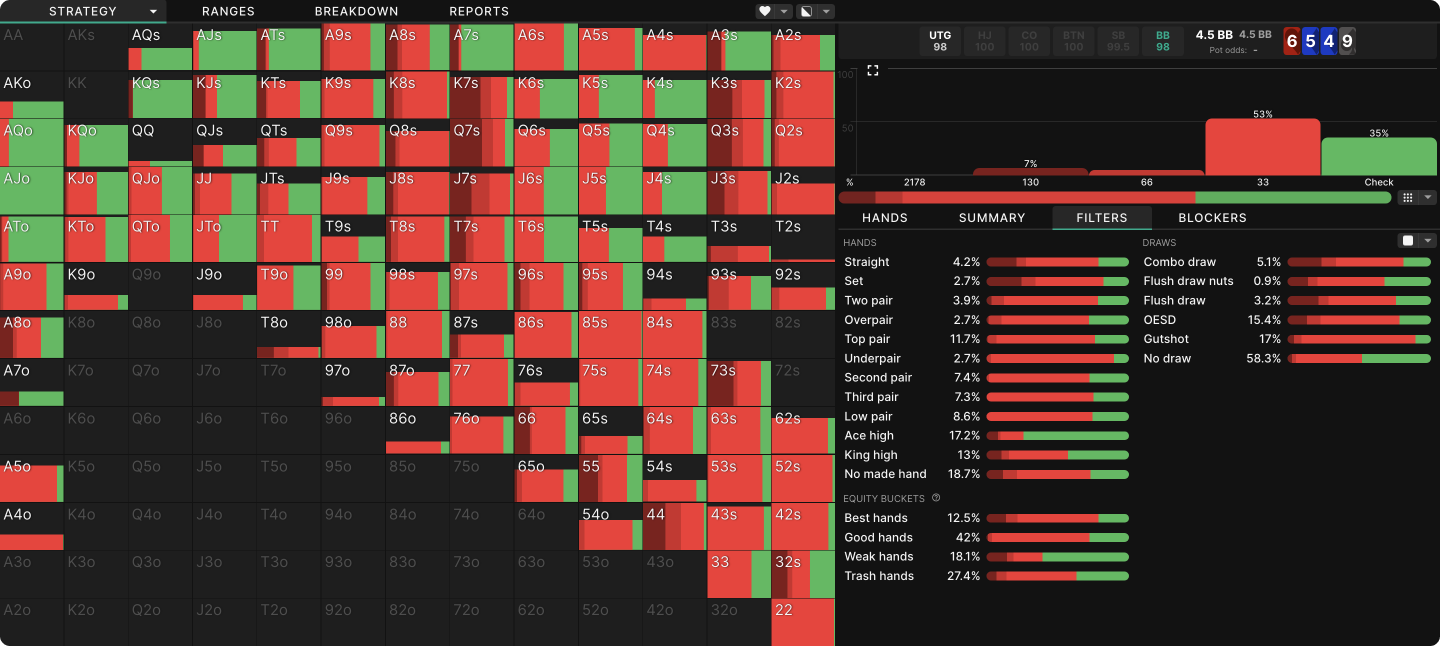

The example we will investigate is A♦ K♥ 8♥, on which LJ enjoys a massive range advantage but has a small checking range of about 10%. First, here’s the equity graph showing the extent of LJ’s advantage.

The LJ has a massive equity advantage, with 65% of the equity, plus has nutty hands like AA, KK, and AK at a far higher frequency than BB. As a result, they could profitably bet any two cards, but they do a bit better by occasionally checking behind. Unlike on the 333 flop, LJ’s medium-strength hands like A2, K6, and JJ have little to protect against by betting. Betting is not bad per se – it often wins the pot – but it does not accomplish much that checking would not. Barring a lucky catch, these hands will not be strong enough to keep betting if called, and any hand BB folds would have little chance of winning anyway.

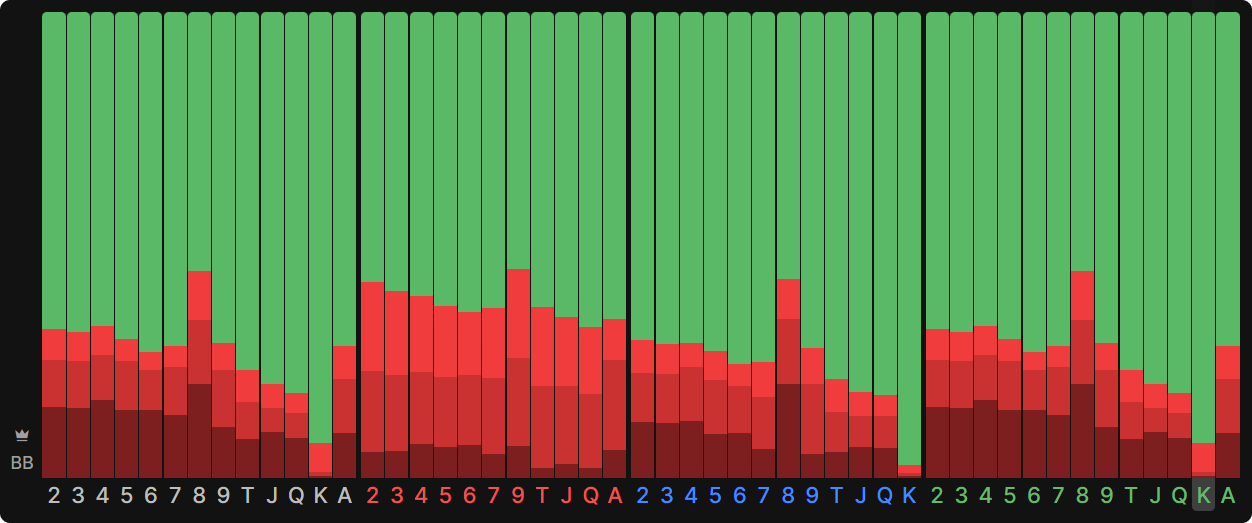

The upshot of all this is that LJ’s checking range is a bit capped but still quite strong. Not many weak hands check, because the immediately profitable flop bet is a tempting proposition for them. That means BB can’t start firing turns with abandon, because they will still be at an equity disadvantage. Indeed, there is no turn BB bets at higher than 50% frequency.

Notice also that when they do bet, they often use a large size, indicated by the darker red in the chart. This is the BB leveraging their nuts advantage to bet a polarized range and deny equity to LJ’s medium-strength hands, which become marginal bluff-catchers at best. BB has only so many nutty hands, however, so can’t bet too often or else bluff-catching would be solidly profitable for LJ. They mostly check, no matter the turn card, often intending to fold just as they were going to do on the flop.

When BB does bet, they are betting into a strong range and cannot expect to profit from fold equity alone; their bluffs need a chance of winning when called. Their bluffs on a 4♠ turn, for instance, are all flush draws and gutshots (the low ones, not the Broadway draws). They pure check and fold their worst hands.

Because they check so many weak hands, they are also incentivized to check some strong ones. Sets, two pairs, and even AJ and AQ are candidates for check-raising.

As with their bets, their check-raise bluffs are all draws. The major change to the bluffing range is the addition of some 4x, which was too strong to bluff with when first to act but loses some of its value once LJ bets. The 4 is a significant blocker, because LJ’s nuttiest hands are turned sets and two-pairs.

Once the flop comes AK8, BB simply should not put too much money into the pot no matter what happens on later streets.

Such is the extent of the LJ’s range advantage on this flop that even if LJ declines to bet the flop and turn, BB still has a high checking frequency on most rivers. Once the flop comes AK8, BB simply should not put too much money into the pot no matter what happens on later streets. Favorable action and runouts can improve their prospects at the margins, but their strategy always entails a lot of checking and folding.

Less Favorable Flops

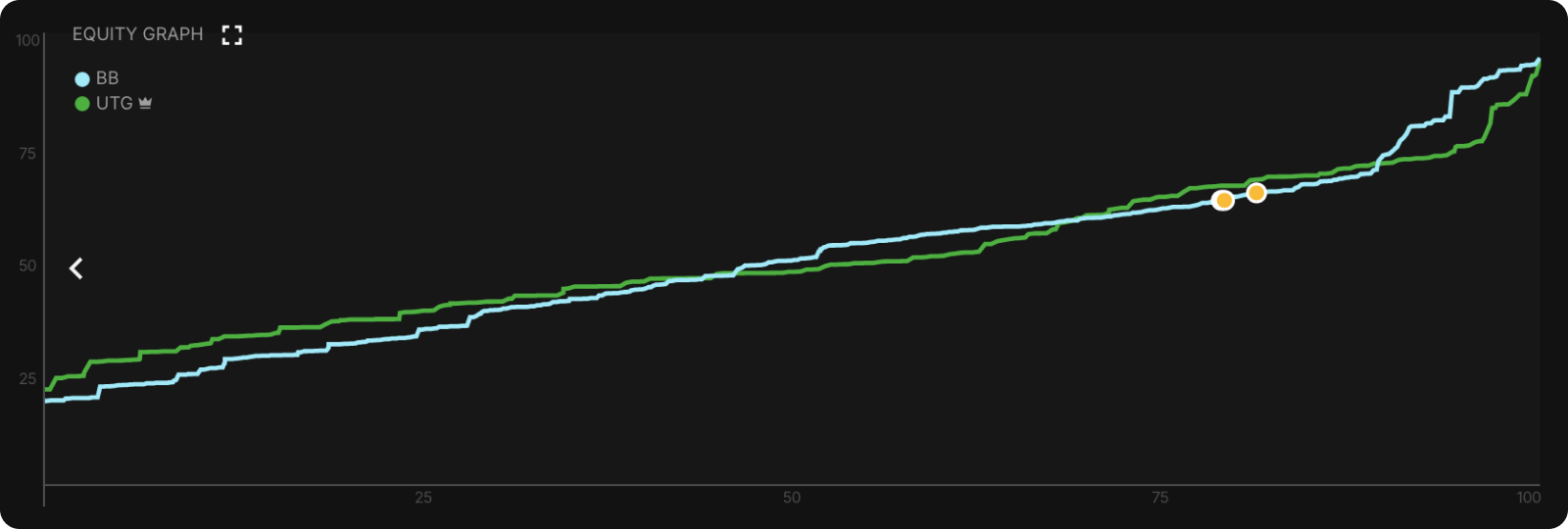

Flops that do not favor the preflop raiser are uncommon, but they are also the flops the raiser checks most often. On 6♥ 5♦ 4♦, for example, equity is split almost exactly 50-50 between the LJ and BB, with the BB enjoying the nuts advantage. Consequently, the LJ rarely continuation bets, and their checking range contains more weak hands simply because they have more weak hands on flops that do not connect well with their Broadway-heavy range.

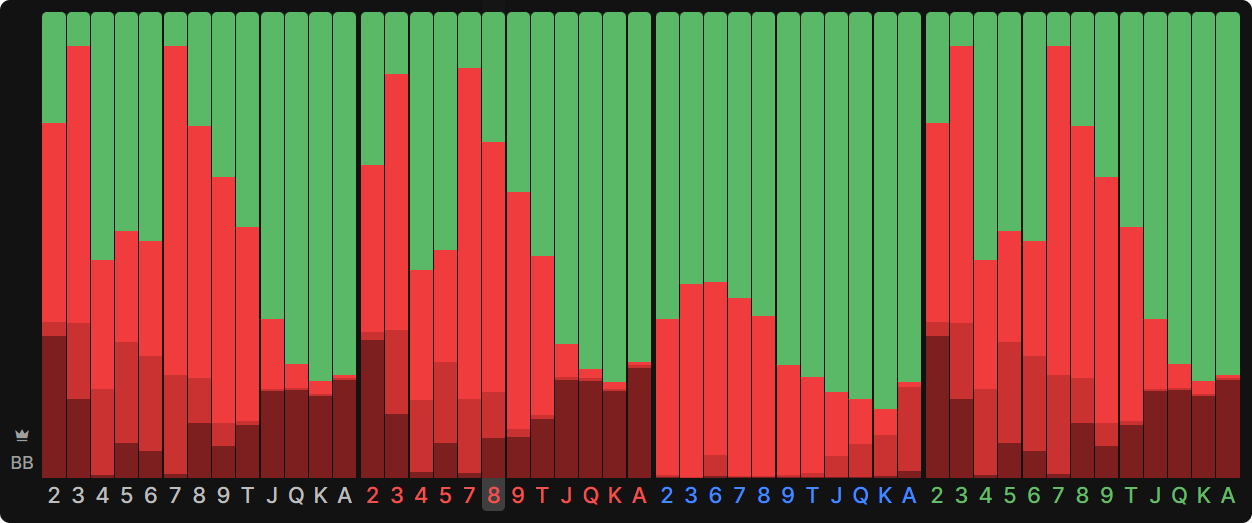

How BB plays the turn depends heavily on which card comes, far more so than on the static AK8 flop. When small cards turn, they enjoy a significant range advantage and can bet liberally, including with marginal pairs that benefit from denying equity to the many overcards in LJ’s range.

When big cards turn, LJ’s equity improves and BB’s strategy looks more like it did on the AK8 board, betting a more polar range at a lower frequency:

BB’s threshold for betting on, say, a 9s turn is much lower than for betting any turn on the AK8 board. They can bet any pair for value and protection, and they can bluff with no-pair, no-draw hands, which still have some equity when called thanks to their pair outs. Their checks are mostly Ace-high, which has some showdown value, rather than very weak hands, which are simply giving up.

Conclusion

The preflop action and the cards on the flop establish strong baselines for how much equity each player is likely to have. The actions each player takes and the cards that come on later streets do not reinvent the wheel; a player with a big equity advantage on the flop does not lose that advantage simply because of one bad turn card or a “weak” action like checking.

A player with a big equity advantage on the flop simply holds many more strong hands than their opponent.

A player with a big equity advantage on the flop simply holds many more strong hands than their opponent. That means they can and should spread those strong hands across their ranges, so that even though they are incentivized to bet their strongest hands, they still have plenty of reasonably strong hands to check.

On flops where the equity is distributed more evenly, correct strategy on later streets depends more heavily on the action and finally community cards.

A check from the preflop raiser is a condensing action, making nutty hands less likely for them. Thus, it is usually correct for their opponent to do some amount of polar betting on the next street with their newfound nuts advantage. Whether they also get to bet more thinly for value and protection, however, depends heavily on how the board texture distributes equity among the players.

Author

Andrew Brokos

Andrew Brokos has been a professional poker player, coach, and author for over 15 years. He co-hosts the Thinking Poker Podcast and is the author of the Play Optimal Poker books, among others.