Slow-Playing

Slow-playing, like running a big bluff or making a heroic call, feels great when it works. It feels like you are winning by wits alone, playing your opponent like a fiddle as you cajole them into throwing ever more money into a pot they have no chance of winning.

The danger of this good feeling is that it may seduce you into slow-playing when it is not wise to do so, costing you many chips, if not the entire pot. Ultimately, you want to play big pots with your big hands, so it’s best to find ways to create deception while still putting chips into the pot.

In this article, we will consider the incentives around slow-playing:

- What are the risks?

- What are the rewards?

- And when is it just fancy play syndrome?

What Is Slow-playing?

You probably have some idea already, but for the sake of clarity, when I talk about slow-playing, I am talking about:

Deliberately taking a passive line—checking and calling—with a hand strong enough to bet or raise for value.

The purpose of slow-playing is to deceive your opponent into thinking your hand is weaker than it actually is. To keep things simple, I will generally talk about slow-playing the flop, but similar considerations will apply to slow-playing before the flop or on the turn (or on other streets, in other games—the material in this article is not terribly specific to Hold ‘em).

Incentives and Deception

Deception is not an end in itself.

Your ultimate goal when you hold a strong hand is for the pot to grow. Deception is valuable only insofar as it causes your opponent to put more money into the pot than they would have had you played your hand more aggressively.

For an extreme example, suppose you checked the nuts last to act on the river. That would certainly be deceptive, but it would not accomplish your goal of playing for big pots with big hands. This example may sound ridiculous, but in fact, people make ridiculous, counterproductive slow-playing decisions all the time because they fixate on deceiving their opponent rather than on growing the pot.

Deception in poker is not necessarily about playing a hand contrary to its incentives. Often, you can be just as deceptive by playing your hand in a way that is perfectly aligned with its incentives but which could also credibly represent a different sort of hand with different incentives.

An Example

Suppose you open the BTN in a 100bb cash game and the BB calls. You bet 125% pot on a K♠9♥5♦ flop and 125% pot again on a 2♣ turn.

Is this a deceptive way to play a set of fives? Why or why not?

From one perspective, it sure looks like you have a strong holding. You’re shoveling money into the pot, with the threat of an all-in bet looming on the river. That’s exactly what you’d like to do with a very strong hand, and your opponent has good reason to fold for fear that you may have one.

But they also have good reason not to fold because, from another perspective, this is also exactly what you’d like to do with some of your weakest holdings. Precisely because this is how you’d like to play a strong hand, it’s a good, deceptive way to play a weak hand. And vice versa. Playing strong and weak hands in this way gives both the opportunity to accomplish their objectives and puts your opponent in a genuinely tough spot.

In other words, it creates deception without compromising the incentives of each hand in the range:

- To grow the pot, in the case of a strong hand

- And to steal the pot, in the case of a weak hand

As it happens, the solver takes this line with both strong hands (such as sets) and weak hands (such as gutshots).

What Does Slow-playing Represent?

In my experience as a coach, people tend to be very aware of “telling a story” when they are bluffing. That is, they think about what they are representing and why it is plausible they could have that strong hand instead of the weak one they currently hold. But storytelling is just as important when you have a strong hand! In either case, the aim is to deceive your opponent by credibly representing a hand other than the one you currently have.

When you check the flop, you may be telling the story that you are weak. But as soon as you put chips into the pot after checking, the jig is up. It no longer looks like you have a weak hand because weak hands usually fold after checking.

Checking and calling looks like either a medium-strength hand or a trap. That’s not necessarily a problem, as representing a middling hand could entice your opponent to run a big bluff, but you should be aware of what you’re representing so your play (storyline) remains coherent on later streets. If, after checking and calling, you come out with a massive bet on the river, that’s not consistent with a medium-strength hand, nor is it the best way to win money from your opponent’s bluffs, which is what you were presumably trying to induce by checking and calling in the first place.

Risk 1: Giving Free Cards

The obvious risk of slow-playing, the one people are most aware of, is the risk of a free card costing you the pot. The less obvious risk is failing to grow the pot, which, as we will see, can cost you quite a lot of potential winnings even when it doesn’t cost you the pot itself.

Most humans tend toward loss aversion, an excessive concern for holding on to what they already have, even if it means missing opportunities to gain more than they would put at risk. It is understandable, then, that the average poker player would worry more about the risk of losing a pot they are currently winning than the risk of missing out on future winnings. Winning a big pot feels good, and your brain may deliver roughly the same dopamine hit for whether you win $500 or $700, whereas it may punish you excessively if your choice to slow-play costs you a pot your brain was already counting as its own.

This is not to say that the risk of giving free cards is negligible, only that it tends to get too much attention in discussions around slow-playing. In particular, people tend to fixate on the wrong ways in which a free card could hurt them.

A free card costs you the pot only if the hand that improved to beat you would have folded to a bet.

Big, obvious, strong draws like flush draws and open-ended straight draws don’t generally fold to bets, so while slow-playing may cost you the opportunity to put money in as a small favorite against those draws, it doesn’t cost you as big of a pot when they draw out.

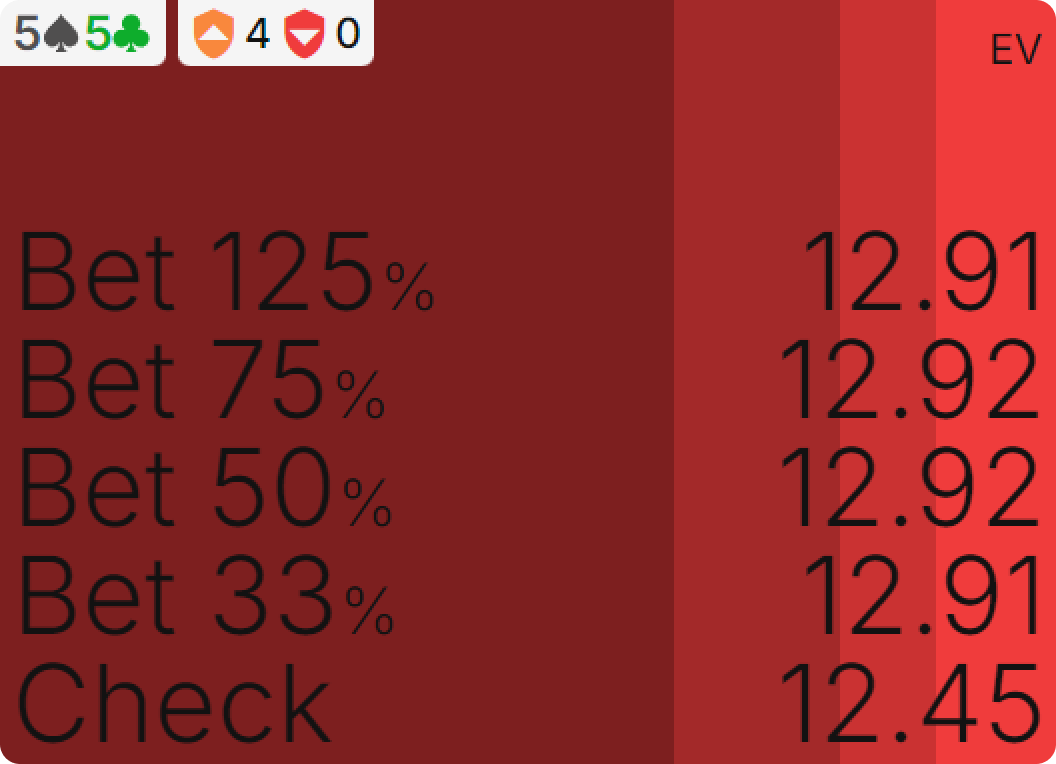

The scenarios where a free card really costs you dearly are when a hand that would have folded hits an unexpected miracle. If you check 55 on that K♠9♥5♦ and your opponent holding 66 turns a bigger set, you aren’t costing yourself just the current pot but additional bets on the turn and river as well. It’s not a likely scenario, but it’s expensive when it happens.

Risk 2: Failing To Grow the Pot

The other risk of slow-playing is failing to grow the pot, which can result in winning much less when your opponent has a hand that would have put more money into the pot. Suppose you flop a royal flush against a very special opponent. This opponent will sometimes fold to flop bets, but they never fold to pot-sized bets on the turn and river. With $100 in the pot, you have a choice between two betting lines:

- You can bet 30% pot on the flop, 100% pot on the turn, and 100% pot on the river. Or,

- You can check the flop, bet 100% pot on the turn, and 100% pot on the river.

How often does your opponent need to fold the flop in option 1 to make it worse than option 2?

It’s easy to calculate what option (2) is worth. Your opponent never folds, so you win a $100 bet on the turn, a $300 bet on the river, and the starting pot of $100, for a total of $500.

When your opponent calls your $30 flop bet in option (1), you then bet $160 on the turn and $480 on the river, plus the starting pot, for a total of $770. Missing out on one small bet might seem like a small price to pay to get two big bets guaranteed on the turn and river, but because that small bet sets you up to make even larger bets on the later streets, you lost out on not just the $30 bet but a total of $270 over the course of the hand. Your opponent would need to fold the flop more than 40%Let x be the flop fold%:

EV(Line 1) = $500

EV(Line 2) = (1-x)($770) + $100(x)

—

Set EVs equal to each other to find x:

EV(Line 1) = EV(Line 2) when x = 40% of the time to the 30% pot flop bet to make option 1 less desirable!

But There Are Also Rewards

Real poker is much more complicated, of course, but this simple example demonstrates one common effect of slow-playing:

Checking the flop with a strong hand often makes it more likely you will get two bets, but less likely you will get three.

There are three primary means by which checking might induce your opponent to put in bets on later streets with hands that would not have paid you off otherwise :

- They had a weak hand on the flop and would’ve folded, but the turn improves them to a second-best hand with which they are willing to pay off bets.

- Checking induces them to bluff with a weak hand that would have folded to a flop bet.

- Because you are generally incentivized to bet your strongest hands, they correctly lower their standards for putting money into the pot on future streets after seeing you check the flop.

Timing Your Slow Plays

In light of the above risks and rewards, we can reach some conclusions about when slow-playing may be desirable. Recall the two major risks of slow-playing: getting outdrawn and failing to grow the pot. When neither of these represents a grave concern, slow-playing becomes more desirable.

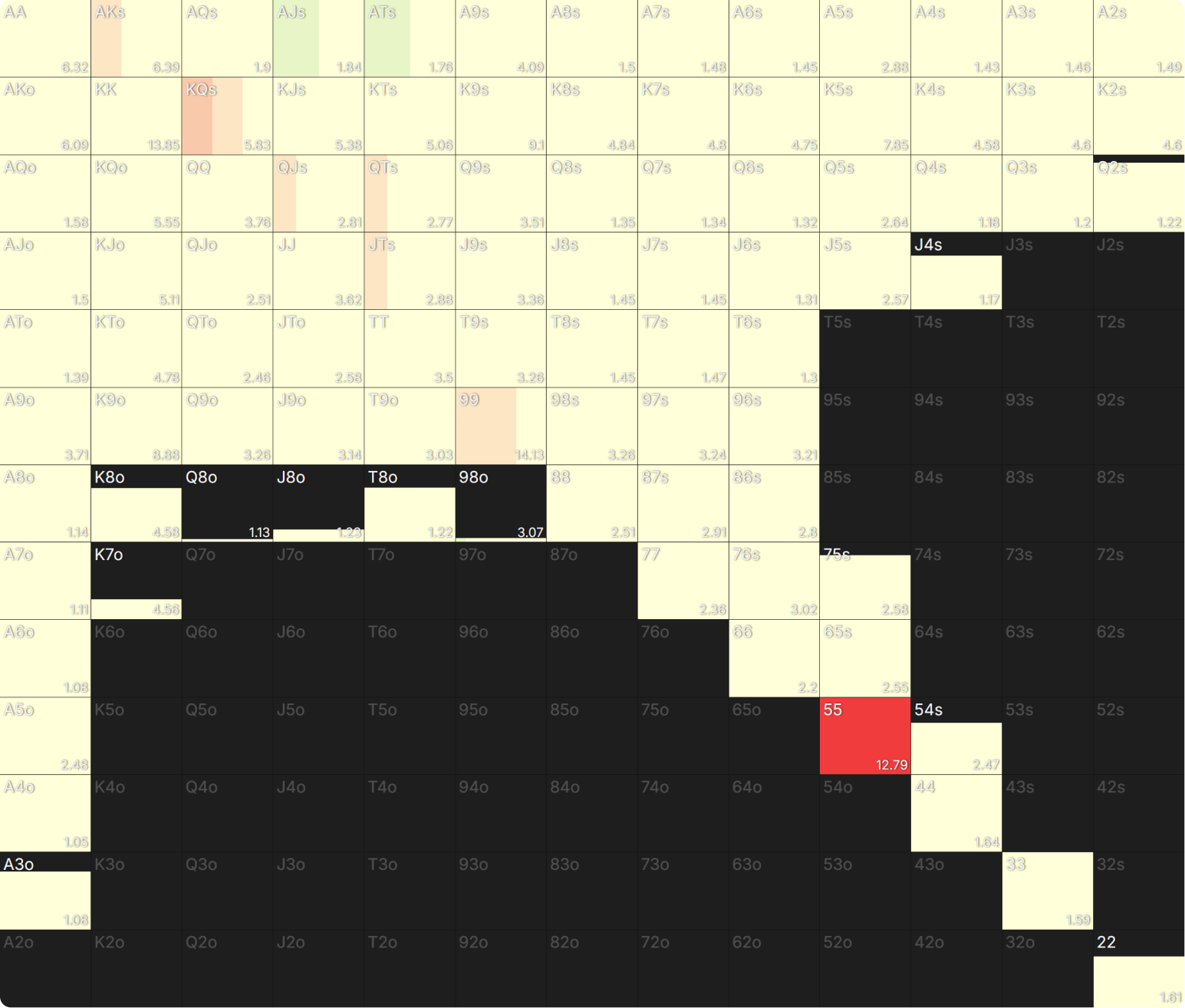

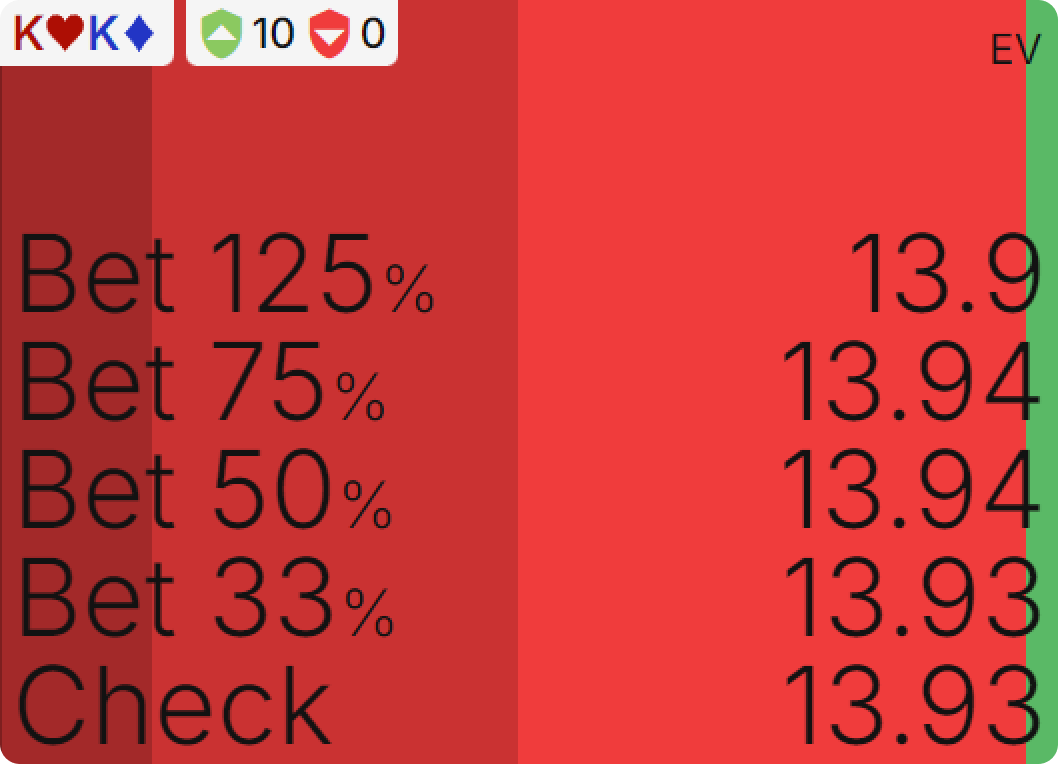

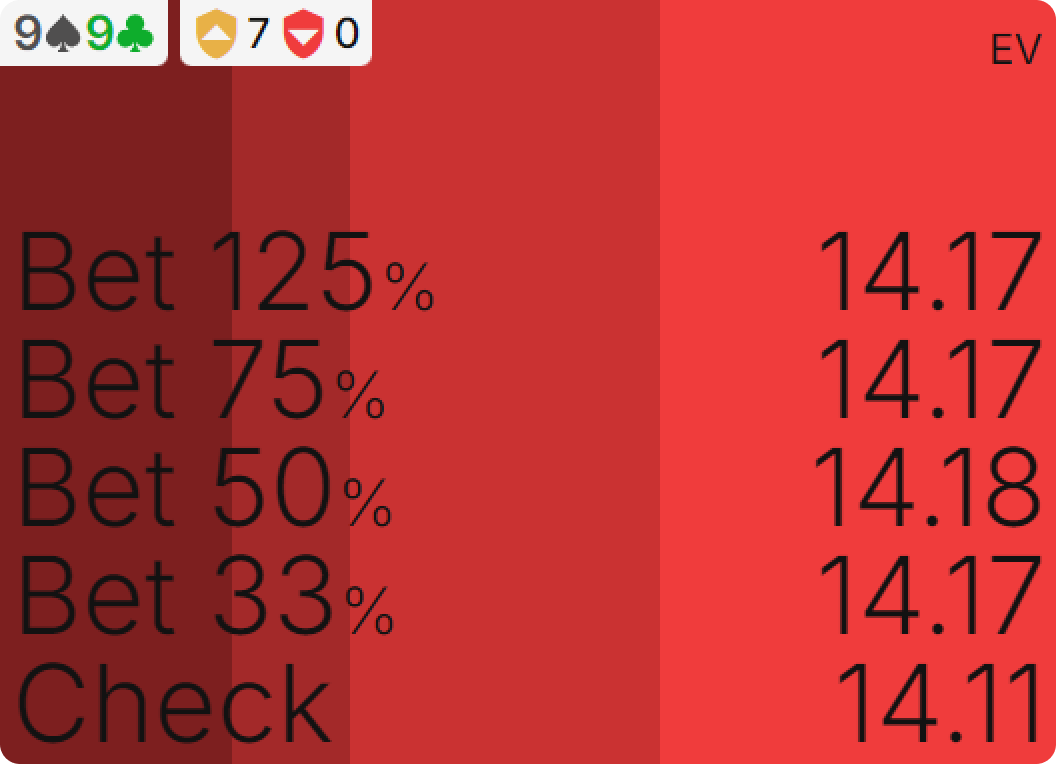

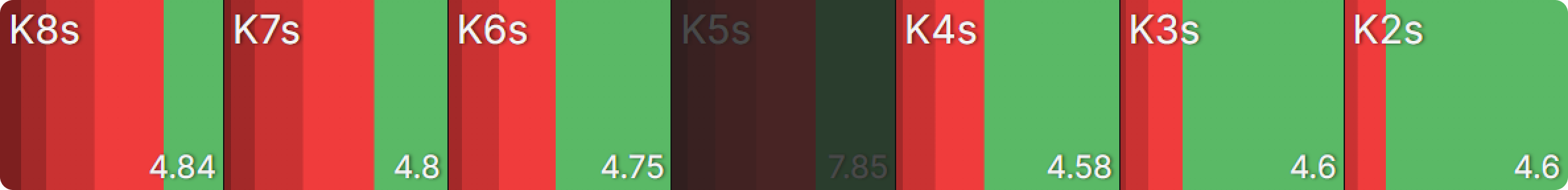

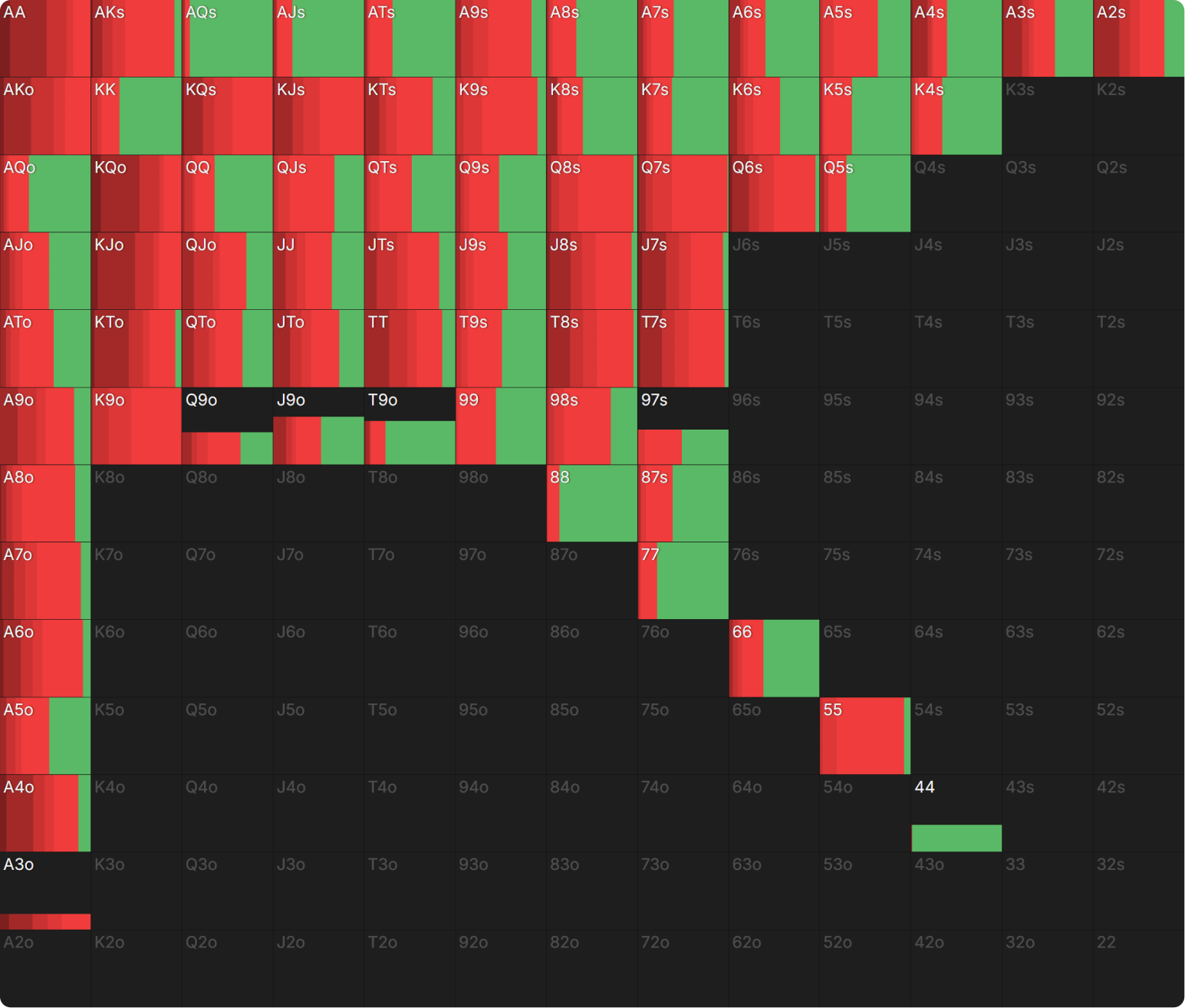

On that K95r flop we’ve been talking about, very few hands show a strong preference for betting over checking. The few that do include 55 and 99, but not KK. Why do you think that is?

The hands most likely to call you down on three streets have a King in them. So, the cost—in the form of missed out on benefits—of slow-playing KK is less than the cost of slow-playing lower sets because, when you so heavily block the BB’s King-x hands, you are unlikely to get three bets paid off anyway. This is also why a set of Nines has higher EV than a set of Kings.

Another argument for slow-playing is when your hand simply is not strong enough to value-bet three times. In that case, checking doesn’t cost you a bet because you weren’t going to bet three times anyway.

Checking as a slow play doesn’t cost you a bet when that extra bet couldn’t be profitably made.

BTN often slow-plays their weaker Kings on this flop because they are tough to draw out on—only one larger card could fall—and won’t bet three times unless they improve:

You may not think of this as slow-playing, but that’s essentially what it is, and there’s an important point here:

The best hands for slow-playing are often not your very strongest hands, with which you’d like to be growing the pot, but rather hands that are tough to draw out on but also not so strong they want to grow an enormous pot.

This is especially true when it comes to inducing bluffs, which is one of the three rewards of slow-playing we identified earlier.

Top pair with a bad kicker beats bluffs just as surely as bottom set does, and it gives up a lot less when it checks to induce.

If you have ever seen young children play soccer, you will understand this concept intuitively. Before they understand the concept of (or have the necessary discipline for) playing position, children just swarm the ball, everyone trying to kick it all at once. There is nobody to pass to and nobody playing defense because they are all in a pack around the ball.

Hands in your range are like players on a soccer team: some fit certain roles/positions better than others, and your team will perform best when everyone sticks to their role/plays their position. Very strong hands excel at betting for value, so that is generally the position they should play. Medium-strength hands are better assigned to the bluff-catching position, especially when they are tough to draw out on.

If you assign all your players to catch bluffs, then you’ve got no one playing offense, a strategy that will perform about as well as those five-year-olds swarming the ball. They’re cute, but it doesn’t take Real Madrid to beat them. Even a team of slightly older children, executing slightly better on the game’s fundamentals (roles), will pick them apart.

Shallow Stacks

There is another case where checking is unlikely to cost you a bet with your strongest hands: when the stacks are so shallow that you don’t need three bets to get all-in. A 20bb sim for the same K95r flop shows a high frequency of slow-playing KK and 99:

(Even at 40bb, the lower sets sometimes slow-play.)

Note that other strong hands such as AA, AK, KQ, and KJ purely bet. Of course, they don’t require three streets to get stacks in any more than 99 does, but they are more vulnerable to free cards. With the pot being larger relative to the stacks, the reward for slow-playing is reduced, making the risk of getting drawn out on a greater concern for more vulnerable hands.

Another Way To Slow-Play

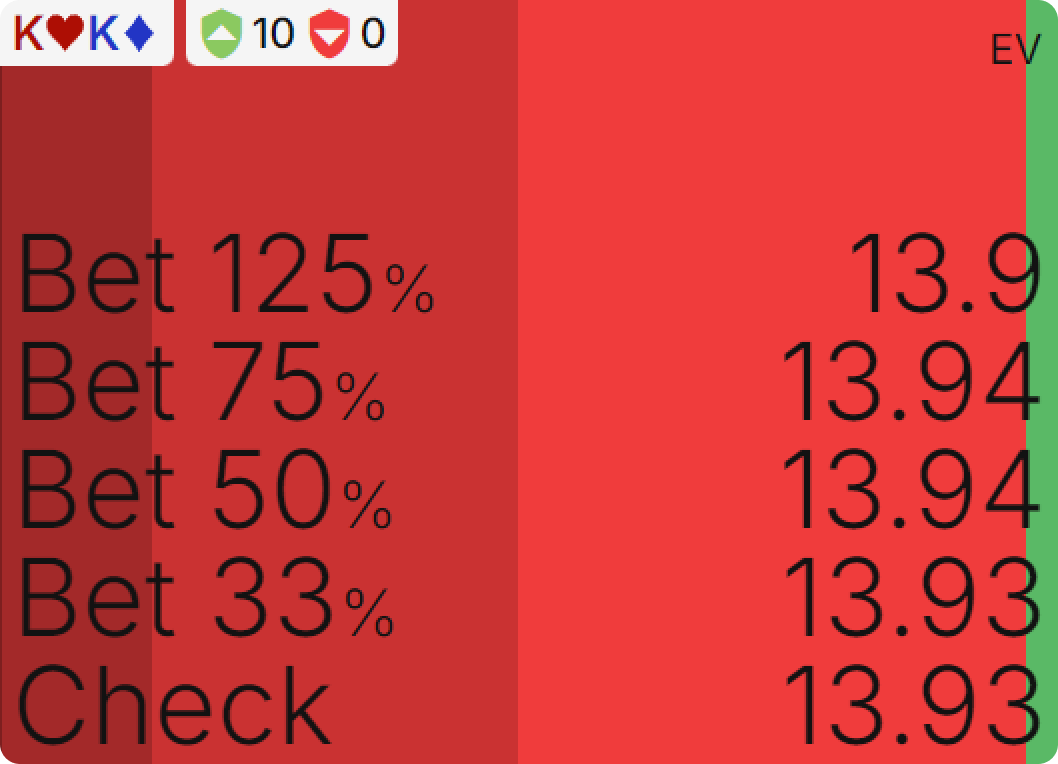

Although KK and 99 do not really check in the 100bb equilibrium, they do often bet small. This is true despite the fact that BTN often uses larger bet sizes, including with these hands.

Why does a solver expect betting 33% pot with Kings to make just as much as betting 125%?

This is, in essence, another form of slow-playing.

A hand can be played slower not only by checking instead of betting (or calling instead of raising), but also by betting small instead of betting large.

A small bet, at equilibrium, performs just as well as a large bet because it can induce bluffs (raises, in this case) and light calls, including from hands that would have folded to a larger bet but could improve to something still worse on the turn.

A small bet is at least as consistent with how BTN would play some weak hands as checking is, and it has the added benefit of growing the pot. We have already seen how heavily even a small flop bet can increase your winnings on later streets compared to a check. KK is a good candidate for this play, just as it is for checking, because it blocks so many of the hands that would call a larger bet.

If BB calls this small bet, BTN can start growing the pot more dramatically with an overbet on the turn or continue “slow-playing” with another smallish bet. KK is once again a better candidate than 99 for the slow-playing option because of its blockers.

Conclusion

Understanding the risks and rewards of slow-playing can help you better decide, in real-life game situations, which of these options is suitable with a given hand. As we saw in these examples, the equilibrium EVs often run quite close between checking, betting small, or betting large. But that does not mean they will actually be close against a human opponent!

Will this player check-raise as aggressively as a solver would against a small c-bet? Will they fire big bluffs, possibly even overbets, if you check the flop? Will big bets make them suspicious, such that they call down light?

Setting aside these human factors, there are structural considerations as well. Is a free card more likely to improve your opponent’s weakest holdings to second-best hands or to something stronger than your monster? How large is the pot? How much remains in the stacks? Do you block the hands most likely to play a big pot with you?

That’s a lot to consider, but the better you can manage that, the better your slow-playing decisions will be. But a good rule of thumb for slow-playing is: when in doubt, don’t. You want to play big pots with big hands, and the most straightforward way to do that is simply to bet or raise at every opportunity.

Author

Andrew Brokos

Andrew Brokos has been a professional poker player, coach, and author for over 15 years. He co-hosts the Thinking Poker Podcast and is the author of the Play Optimal Poker books, among others.

Wizards, you don’t want to miss out on ‘Daily Dose of GTO,’ it’s the most valuable freeroll of the year!

We Are Hiring

We are looking for remarkable individuals to join us in our quest to build the next-generation poker training ecosystem. If you are passionate, dedicated, and driven to excel, we want to hear from you. Join us in redefining how poker is being studied.