When Is Bluffing Profitable? The Key Factors You Need to Know

When is bluffing profitable? When you expect your opponent to fold!

That’s not a joke, and I don’t say that only because it isn’t funny. When playing against weaker players, you may be able to anticipate that they will fold, or at least that they are likely to defend at lower than the optimal frequency necessary to make your bluffs unprofitable. Bluffing is not generally very profitable, so exploiting opponents who over-fold really is where much of your profit from bluffing will come from. That is not the subject of this article, however.

What Is a Bluff?

Defining a bluff is trickier than you might think. Broadly, it could mean any bet where you are rooting for your opponent to fold, or at least rooting for them to fold hands better than yours. For our purposes, I want to be a bit more specific:

A bluff is a bet that derives most or all of its value from fold equity.

That means little to none of the bet’s value derives from pots won at showdown, whether that be winning unimproved or improving to something that can win at showdown.

- On the river, it’s easy to meet this definition. You can’t improve your hand if your bluff doesn’t work, nor should you expect your opponent to call with a hand even weaker than your own in hopes of improving it.

- Before the river, however, pure bluffs are rare. Most hands have some chance of improving, even if it’s just a backdoor draw or a miracle two-outer.

When I talk about bluffing before the river, I mean betting the worst hands in your range, even if they are not completely hopeless.

Bluffing in the AKQ Game

Perhaps you’ve heard of the “AKQ Game” (sometimes called the “Clairvoyance Game”). In this toy game, both players are dealt a single card from a deck containing one Ace, one King, and one Queen. They ante and are allowed to bet as they could in a real poker game. If the hand goes to showdown, the player with the highest card wins.

Suppose you were dealt a Queen in this game. Your opponent checks, and you are last to act. Should you bet?

Suppose you were dealt a Queen in this game. Your opponent checks, and you are last to act. Should you bet?

You’ve got no chance of winning if you check, but by betting, you may cause your opponent to fold a King. Then again, you also risk getting called by a stubborn King or a tricky Ace.

We’ve got an entire article on how to solve toy games like this one if you’re interested in the details. For our purposes, all you need to know is that the unexploitable strategy is to bluff in proportion to the pot odds your bet offers your opponent.

If you make a pot-sized bet, that bet offers 2:1 odds to your opponent, so you should have one bluff for every two value-bets. You will always value-bet with an Ace and never with a King (because your opponent should never call with a Queen), and you will be dealt a Queen exactly as often as you are an Ace. So, you want to bet 50% as often with a Queen as you would with an Ace, which means you should bet half the time you have a Queen.

Bluffing at this frequency gives your opponent’s bluff-catches (with a King) an EV of $0, the same as folding. That way, you can not be exploited by an opponent who calls always, never, or anywhere in between. That’s the good news.

The bad news is that your bluffs (with a Queen) also have an EV of $0 at equilibrium. In other words, without any insight into your opponent’s calling strategy, you should not expect to make (or lose) money with these bluffs.

- If your opponent folds too much, your bluffs will make money and your value will make that much less, maintaining the equilibrium.

- If your opponent calls too much, your bluffs will lose money and your value will win that much more, maintaining the equilibrium.

The defining feature of an equilibrium is that neither player can unilaterally improve their EV.

- If your opponent defends at the optimal frequency, you will not do any better against them whether you bluff more than, less than, or exactly your optimal bluffing frequency.

- Likewise, if you bluff at your optimal frequency, your opponent will not do any better no matter how often or rarely they call.

In real poker situations, it’s possible for one of you to do worse than the equilibrium by unilaterally changing your strategy, but it is not possible to do better.

Real poker is more complicated. There are many cases where betting your worst hands should show a profit, and there are also many cases where you should expect it to be downright unprofitable, so it is not something you do at any frequency.

Whether or not betting your worst hands should show a profit is mostly determined by what happened on earlier streets.

A River Example

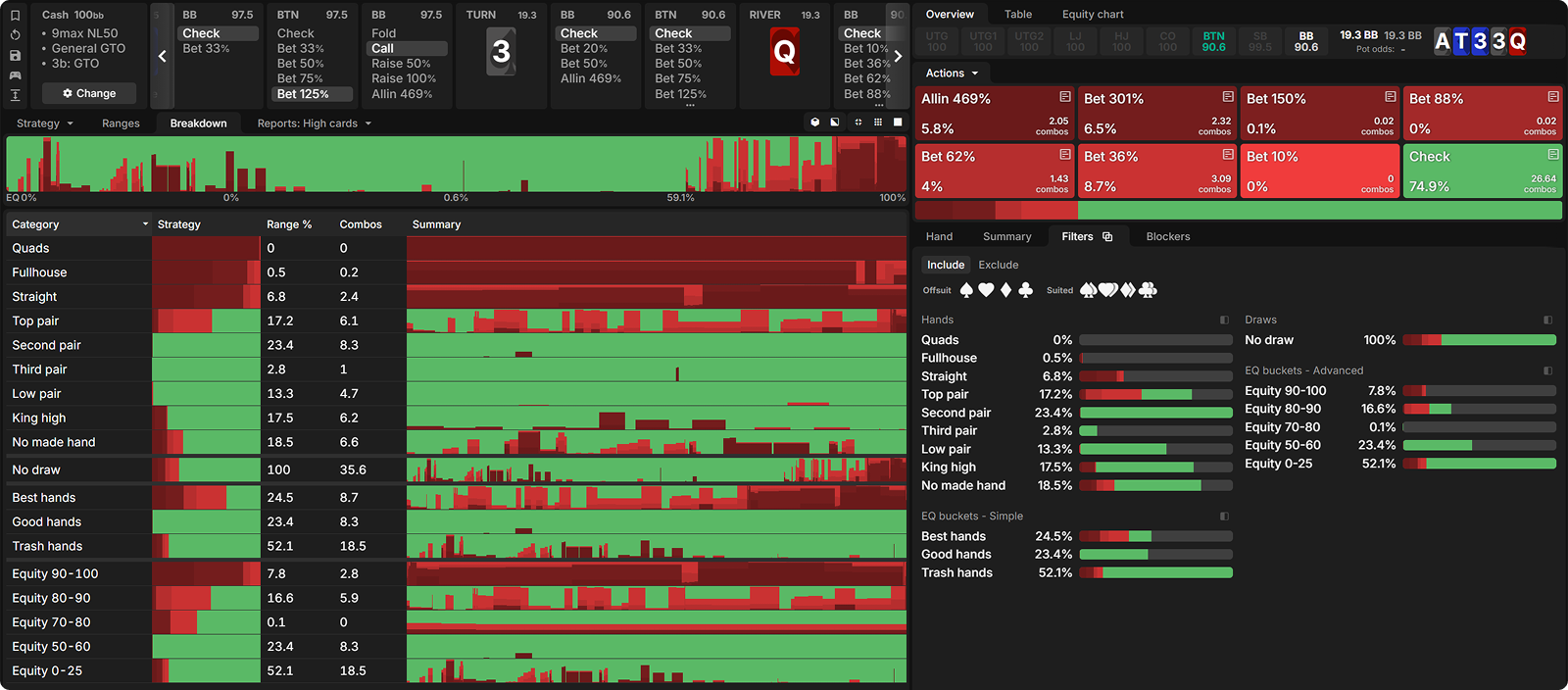

BTN opens 2.5bb in a 100bb cash game and BB calls. On a flop of A♠T♦3♦, BB checks and calls a 125% pot continuation bet. The 3♠ checks through, and the river brings the Q♥.

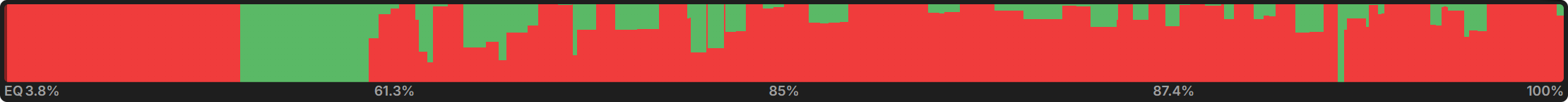

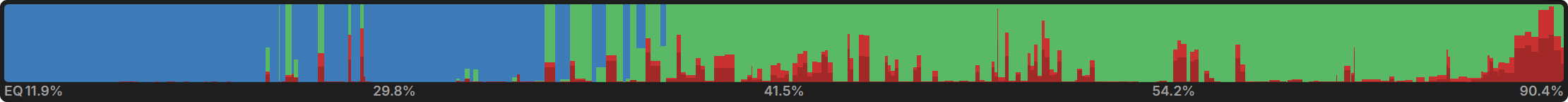

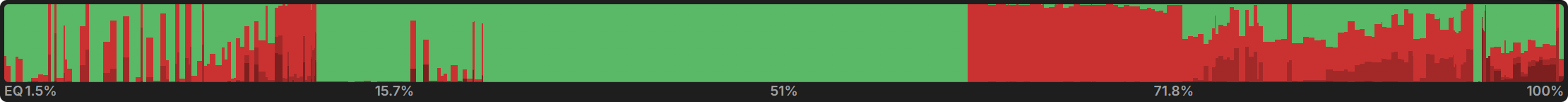

This is the Manhattan plot for BB’s equilibrium river strategy with their entire range, weakest hands on the left and strongest hands on the right. I’ve removed the bet sizes, so the chart simply shows how often BB bets each part of their range, without regard to size:

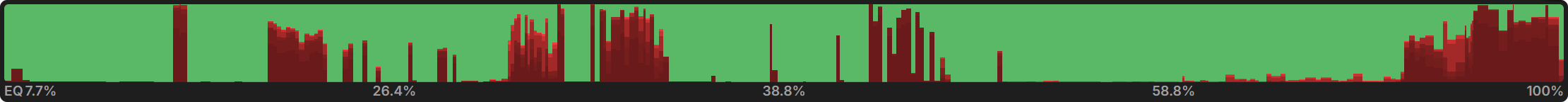

The pure pink on the far left side of the graph means BB always bets their worst hands, stuff like 5♠2♠, which whiffed on the gutshot and backdoor flush draw. These bets must, therefore, be profitable. If BB were indifferent to bluffing, as they are in the Clairvoyance Game, we would expect to see a mix of bets and checks. Here’s the same plot in the Clairvoyance Game:

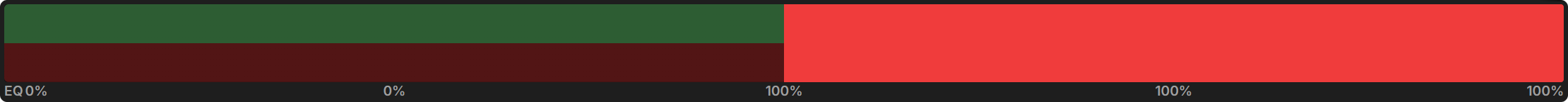

Because BB only bets two hands in the Clairvoyance Game, this graph is easy to interpret. They always bet Aces, and they are indifferent to betting Queens.

That’s not what we see in our river example.

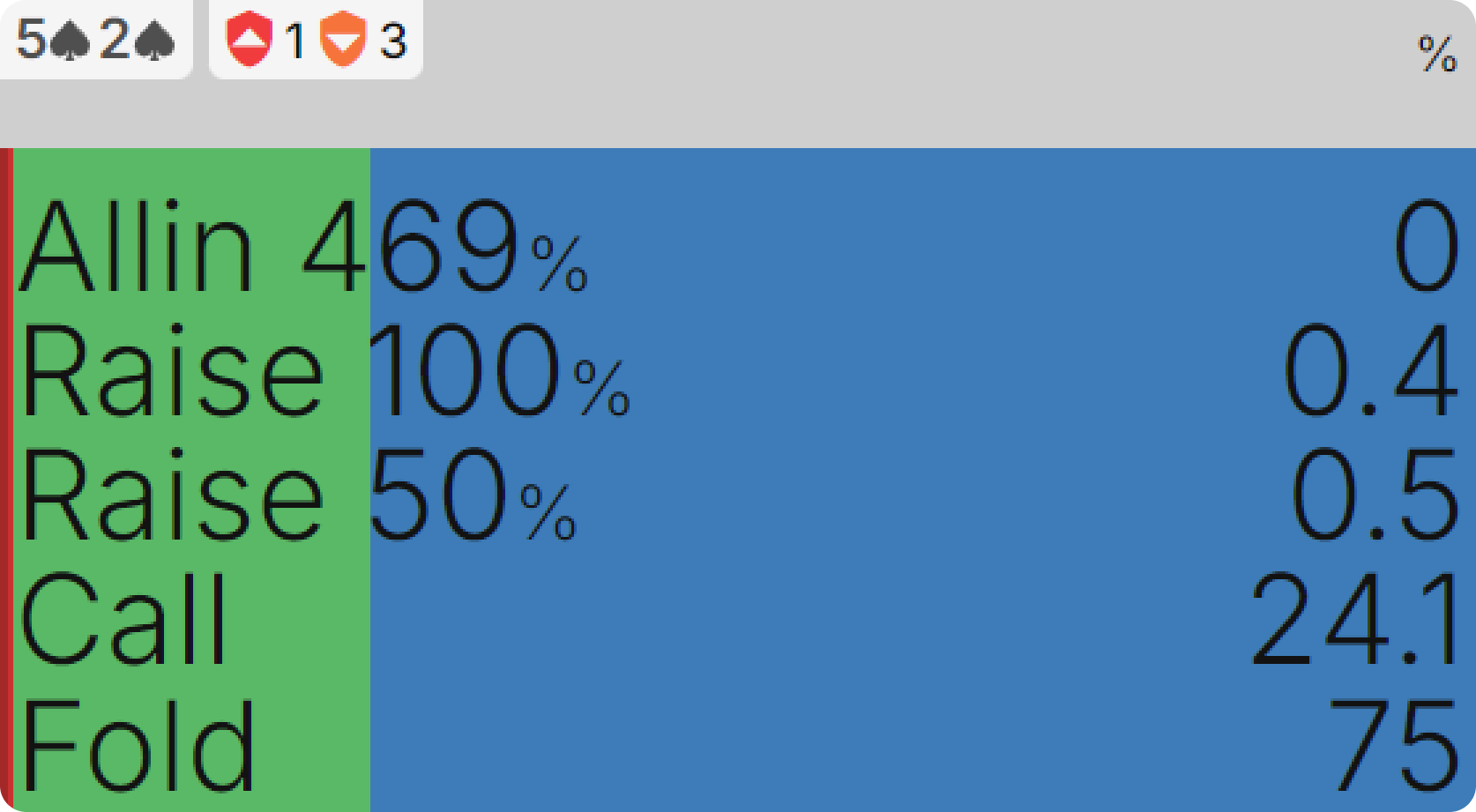

So the question is, why is it profitable for BB to bet their worst hands in this equilibrium? Why doesn’t BTN call more often in order to make BB indifferent to bluffing?

So the question is, why is it profitable for BB to bet their worst hands in this equilibrium? Why doesn’t BTN call more often in order to make BB indifferent to bluffing?

Choose the explanation you think is correct from the four options below, then read on for the answer.

- BB has a reputation for being a nit, so BTN is trying to exploit them by not paying off their river-bets.

- BTN does not have enough potential bluff-catchers to hit MDF, which would make BB indifferent to bluffing.

- BB does not have enough potential bluffs to achieve the bluffing frequency that would incentivize BTN to bluff-catch more than they already are.

- BB’s bluffs are carefully chosen for their blocker effects. When BB has these cards, they block BTN from having as many bluff-catchers as they otherwise would.

Let’s talk about the wrong answers first:

(1) BB has a reputation for being a nit, so BTN is trying to exploit them by not paying off their river-bets. This could be a good reason to fold in a real poker game, but it’s not how solvers work. Solvers don’t make any assumptions about the opponent or how they will play. If the solver is recommending it, then this must be an unexploitable bluffing strategy from BB, which means BTN could not improve their EV by calling more often.

(2) BTN does not have enough potential bluff-catchers to hit MDF, which would make BB indifferent to bluffing. The hands BTN folds are, in fact, stronger than the hands BB bluffs with. Some of these bluffs are as weak as 5-high, after all! That means BTN’s folds are legitimate candidates for bluff-catching. The problem is they lose to too many of BB’s value-bets to make calling appealing.

(4) BB’s bluffs are carefully chosen for their blocker effects. When BB has these cards, they block BTN from having as many bluff-catchers as they otherwise would. Good blockers can make bluffing profitable, but that’s not the primary effect here. In fact, some of BB’s bluffs actually have bad blocking effects, meaning they block BTN’s folds rather than their calls. Yet they are profitable bluffs nevertheless!

The answer is (3) BB does not have enough potential bluffs to achieve the bluffing frequency that would incentivize BTN to bluff-catch more than they already are. BB took a big risk calling that 125% pot bet on the flop. They need a lot of strength to take that risk. Very few weak hands could justify that call.

BTN folds many bluff-catchers even though they know BB would always bluff if they had a weak hand. This is because BB simply shouldn’t have a weak hand very often after calling the flop-bet.

This still leaves us with a puzzle, however. If bluffing is going to be profitable on the river, why doesn’t BB call more weak hands on the flop?

It seems like calling 5♠2♠ is a win-win: either you improve to something strong, or you bluff and show a (small) profit. Yet BB mostly folds this hand on the flop:

Where Range Advantage Comes From

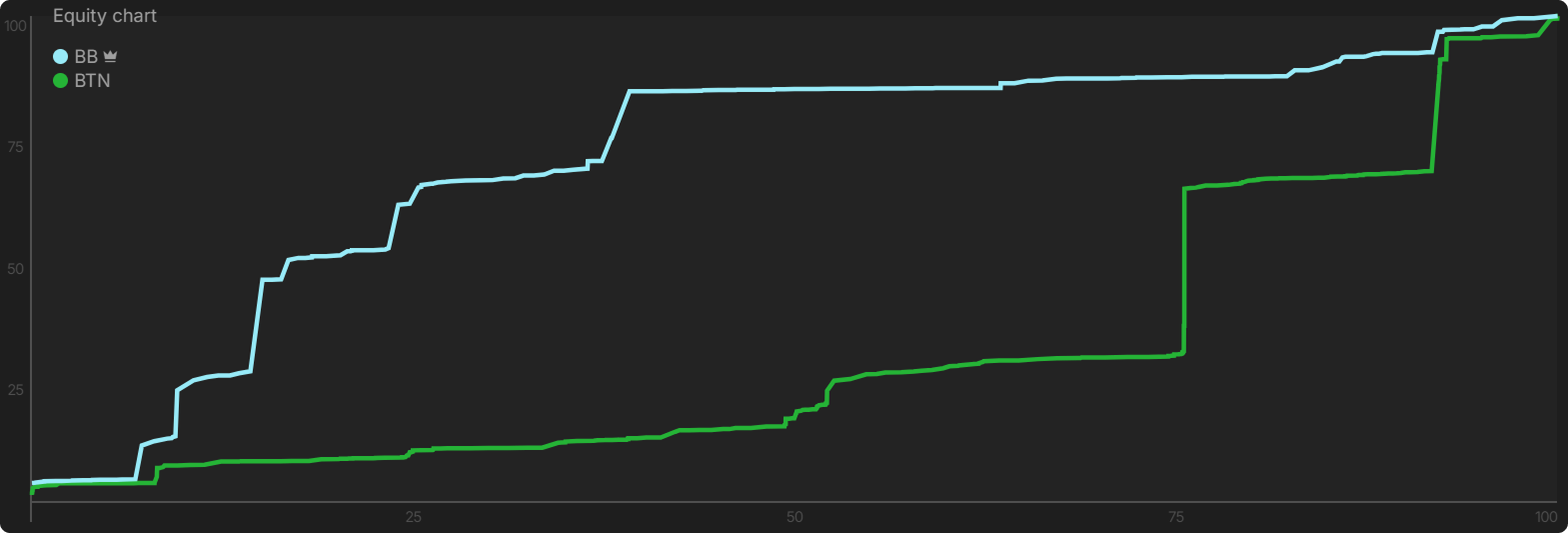

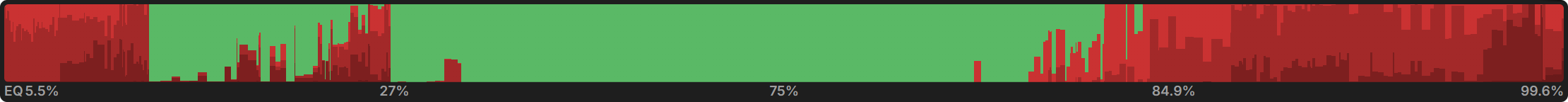

BB gets profitable bluffs in this scenario because their range is much stronger than BTN’s. They have more than 70% of the equity, a dynamic illustrated by this range-vs-range equity graph:

So much of BTN’s range is behind so much of BB’s range that if they called more often, in the hope of picking off bluffs from those very worst hands, BB could exploit them with thinner value-bets.

But that still doesn’t get to the why. Why is BB’s range so much stronger? Why isn’t either player incentivized to do something differently on an earlier street to even out this dynamic?

But that still doesn’t get to the why. Why is BB’s range so much stronger? Why isn’t either player incentivized to do something differently on an earlier street to even out this dynamic?

BB’s Perspective

Perhaps you noticed that I pulled a fast one a few paragraphs back when I said, “It seems like calling 5♠2♠ [on the flop] is a win-win: either you improve to something strong, or you bluff and show a (small) profit.” In fact, there is a third thing that could happen—an event which quite frequently will happen, in fact—that is not so good for 5♠2♠ and which is the reason it is not a pure call on the flop: BTN might bet again on the turn, charging BB a high price to realize their equity on the river and denying them the opportunity to bluff.

The reason this dynamic can exist at equilibrium is that BB does not know, at the time they call the flop, that BTN is going to check behind the turn. If they knew that in advance, then they would call many more weak hands on the flop. But if they were to call more weak hands, then BTN could exploit them by barreling more often.

BB took a big risk with those weak calls, and they got lucky that BTN didn’t have a good barreling hand.

These profitable river bluffs are their reward for taking a risk that panned out.

BTN’s Perspective

BTN, on the other hand, took a risk that did not pay off. They bet the flop, and their opponent did not fold. Of course, not all of BTN’s range wants to see a fold, but much of it—especially much of the range that isn’t going to bet again on the turn—would very much prefer to see BB fold the flop.

BTN’s flop-bet was not nearly as risky as BB’s flop-call. They put the same amount of money into the pot, of course, but BTN had two big advantages going for them:

- They had fold equity. When BTN bets weak hands, they might just win the pot immediately, whereas BB can’t win the pot immediately when they call. BB will sometimes get fold equity on the river after the turn checks through, and that does offset the risk of the flop-call, but they can’t count on that happening consistently.

- Even in case their opponent did not fold, they were in position, giving them better control of the pot. They will be able to check behind the turn when they want to, facilitating free cards and cheaper showdowns.

Range advantage emerges when players take on disproportionate risk at an earlier decision point.

So, when a player fades their worst-case outcomes, they typically have an equity advantage and get to make profitable (as opposed to break-even) bluffs with their weakest hands.

The reverse is also true:

A player who takes on less risk on early streets is typically at an equity disadvantage on later streets and does not bet their worst hands at all.

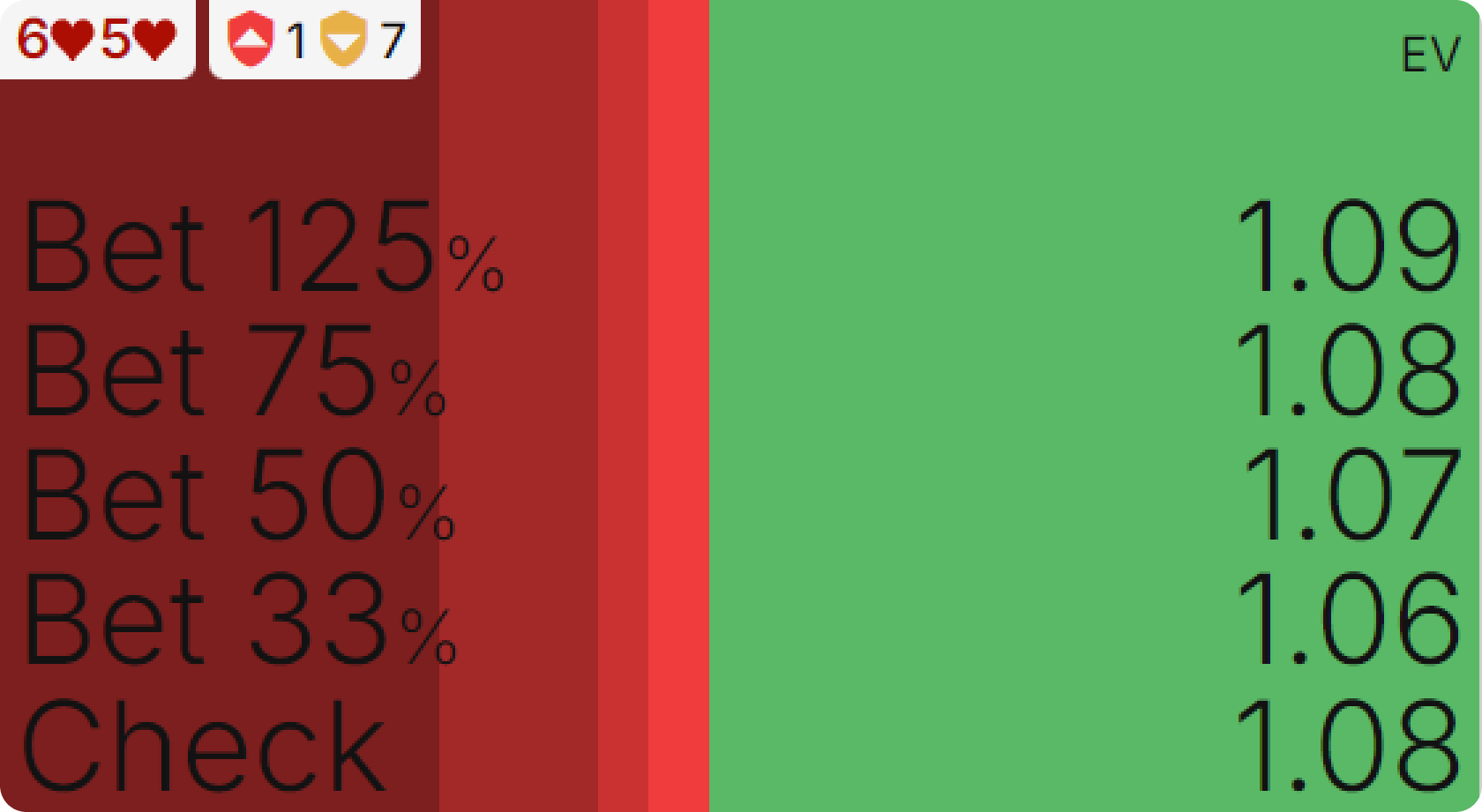

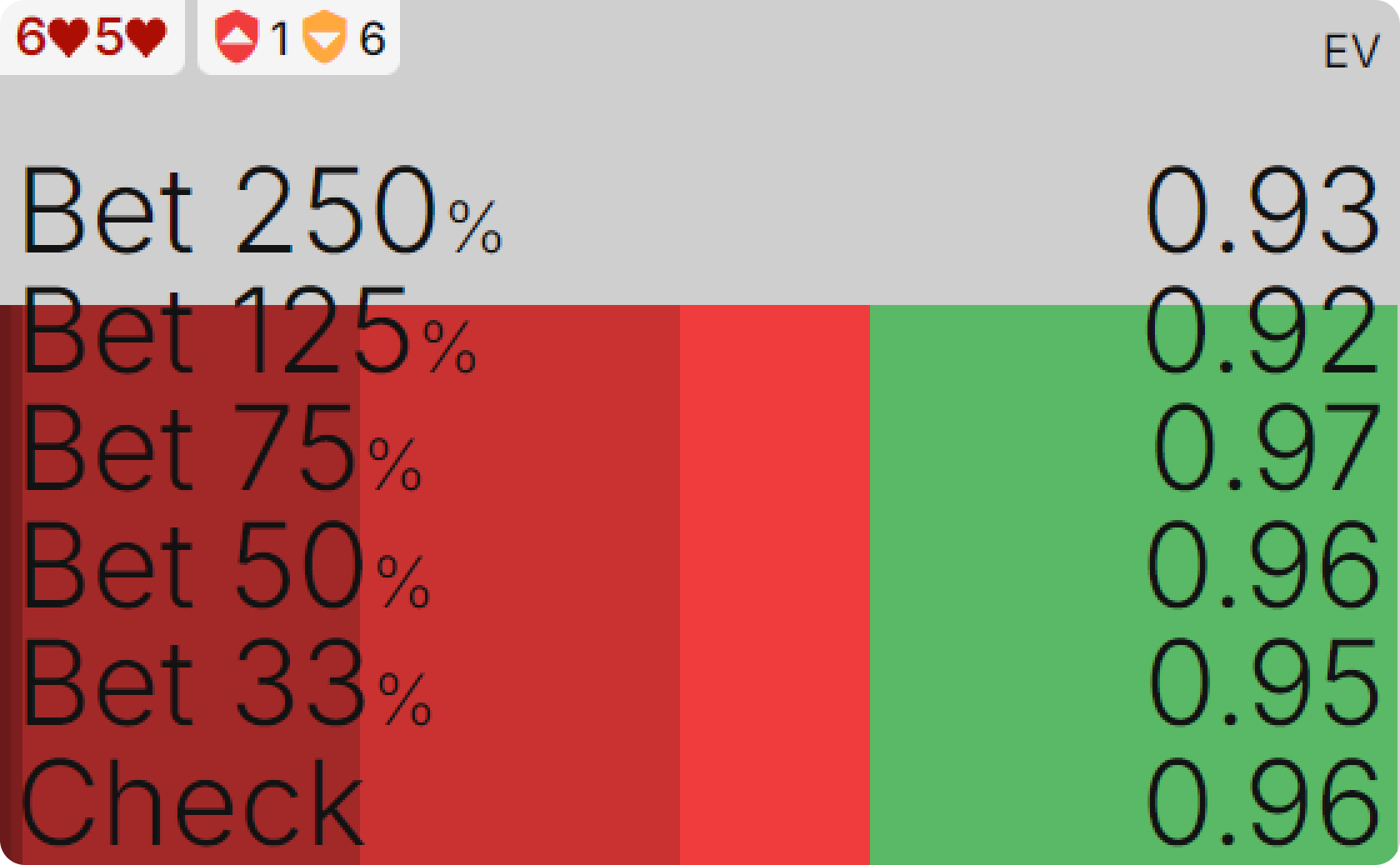

For example, here is BTN’s strategy for the same scenario, facing a BB river check:

With their very worst hand, 6♠5♠, they never bluff. Many other hands with 0% equity are also pure checks, suggesting they would be -EV bluffs. There are no pure bluffs, and the weak hands that mix bluffs are facilitated by blockers, not by an equity advantage.

A Flop Example

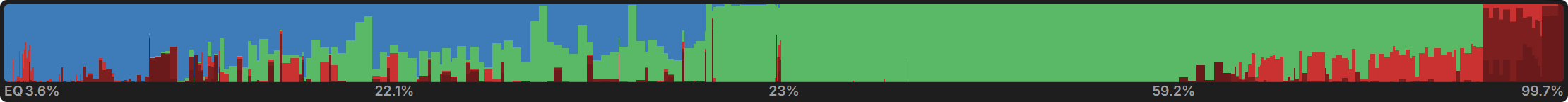

If we back up to the flop in our example, the roles are reversed. BTN took on more risk preflop, so they are the player who sees the flop with a stronger range (55% equity) and the player who can profitably bet their worst hands. 65 without a backdoor flush draw is the stone bottom of BTN’s range, yet even this hand has an EV of greater than 1bb (roughly 20% of the pot) and is a candidate for betting:

BB has no donk-bets on this flop, and were they to face even a small c-bet, they would purely fold many of their worst hands:

Because of their range disadvantage (and, to a lesser extent, their positional disadvantage), they cannot profitably bluff with the bottom of their range as BTN can. It’s not even a mix for them, as it would be in the Clairvoyance Game. Bluffing with their worst hands would lose money, on average.

But let’s get back to BTN’s strategy. In the Clairvoyance Game, a mix of bets and checks meant that bluffing was not profitable. In our river example, BB purely bet their worst hands because it was profitable. But in this flop example, BTN sometimes declines profitable bluffs.

If you’re holding 6-high, no draw, and someone told you that you could claim 20% of the pot with a bluff, that would sound awfully appealing. Why would BTN ever decline to bluff and check such a weak hand instead?

If you’re holding 6-high, no draw, and someone told you that you could claim 20% of the pot with a bluff, that would sound awfully appealing. Why would BTN ever decline to bluff and check such a weak hand instead?

The Bluffing Voucher

The way I think about this is that when a player fades a risk and arrives at a lucky branch of the game tree, they receive a voucher that can be redeemed for one profitable bluff. That is their reward for the risk they took. Unless some new bit of bad luck comes along, they can cash in that voucher at any time. But they only get to use it once.

BB had to redeem their voucher in our river example because that was their last (reliable) opportunity to do so. They can’t count on check/raising the river, because that would require their opponent’s cooperation, and they should not expect BTN to bet many of the hands they would like to fold out with a bluff.

A Turn Example

If both players check the A♠T♦3♦ flop, BB would still be at an equity disadvantage. So, it would still be unprofitable for them to bluff their worst hands (unless they had especially good blockers):

BTN, however, has not yet redeemed their voucher, so they once again have the option to bluff profitably with their worst hands. It is not their last opportunity, however, so they can just as profitably check and save that voucher for the river.

A Different River Example

If both players check again on the turn, BB finally gets some break-even and/or profitable (with the help of blockers) bluffs on the river.

The operating principle here is similar to our original river example, though the effect is less dramatic. BTN checking behind both the flop and turn was a stroke of good fortune for BB. BB would have called with more weak hands preflop if they knew they would get to see five cards for no additional investment, but of course, they did not know that. They went down a lucky branch of the game tree, and their reward was an upgrade from -EV to 0EV bluffs with the bottom of their range.

As for BTN, this is their last opportunity to redeem that voucher, so if BB checks, all their worst hands are pure bluffs:

Voiding the Voucher

What if BB does not check the river? If BB bets, BTN’s voucher is null and void. They mix some bluffs with their worst hands, but none of them are profitable (if they were, BTN would never fold them).

The bluffing voucher is a lucky reward for fading risk and ending up on a favorable branch of the game tree. If BB bets either the turn or river, that is an unlucky occurrence for the BTN. It is not necessarily a strong hand, but it represents more strength than a check would have, which is why BTN loses their voucher.

They could also lose their voucher in an especially unfortunate event (i.e., flop, turn, or river). That is more rare, however. By definition, a range that is favored before new card(s) are dealt will generally remain favored after the card(s) are dealt. A player’s previous-street equity, in other words, is the average of their equity on all possible runouts. So, it is only the most exceptionally bad turn cards that will disrupt their advantage.

Why Doesn’t BB Beat BTN to the Punch?

We’ve seen several examples where BTN gets profitable bluffs if BB checks but not if BB bets. If it’s that easy to void BTN’s bluffing voucher, why doesn’t BB do it more often? Why not take the initiative and bluff first, pushing BTN off the weak hands, which will eventually bluff out BB’s weak hands if given the opportunity?

They could, and sometimes they do, but it’s risky. When a player with a range advantage checks, there’s still a lot of strength in that checking range. Unless the new card is especially unlucky for BTN, it shouldn’t be profitable for BB to bet any two cards. Yes, BB could sometimes steal the pot from a weak hand that would have stolen it from them if they’d checked, but more often, they would get called or raised.

This risk is what makes BB’s bets strong, alarming, unlucky actions that disrupt BTN’s range advantage.

When a player fades risk whilst having prepared for it, they are supposed to get a reward. That’s what maintains the equilibrium.

When you are in the BTN’s shoes, it may feel bad to check the flop with a weak hand that could have profitably bluffed just to end up folding it to a turn-bet. It’s important to keep in mind that that turn-bet was far from a guarantee.

In fact, another way of looking at this outcome is that you saved money by not bluffing into a hand that wasn’t going to fold.

This is how BTN ends up indifferent between bluffing the flop versus checking the flop in hopes of bluffing later. There are risks to passing up the immediately profitable bluff: they might get an unlucky turn or induce BB to bluff with a hand that would have folded. But there are also rewards: they might get a lucky turn or find out cheaply that their bluff was never going to succeed.

Conclusion

A player acquires range advantage by taking on more risk than their opponent and then fading the worst outcomes (both unlucky board cards and unlucky opponent actions). They retain that range advantage until one of three things happens:

- They cash it in by betting. Betting with range advantage claims a lot of EV from the branch of the game tree where your opponent folds. If they don’t fold, that is an unlucky outcome that strengthens their range (because calling and raising are risky), and you will generally be at a disadvantage going forward.

- An especially unlucky board card(s) disrupts their advantage.

- Their opponent takes a strong action that disrupts their advantage.

While a player has the range advantage, they essentially have a voucher that entitles them to a single profitable (+EV) bluff with even their worst hands. They can use that immediately to bluff or check and (usually) carry their range advantage forward to the next street and bluff then.

For the player without a range advantage, it is usually -EV to bet their worst hands. These players may still bet hands that prefer to get folds, but these will either have especially good blockers or be closer to semi-bluffs, hands with a decent chance of winning when called.

Only when neither player has much of an advantage, as in the Clairvoyant Game, is betting the bottom of the range 0EV for both players.

Author

Andrew Brokos

Andrew Brokos has been a professional poker player, coach, and author for over 15 years. He co-hosts the Thinking Poker Podcast and is the author of the Play Optimal Poker books, among others.

Wizards, you don’t want to miss out on ‘Daily Dose of GTO,’ it’s the most valuable freeroll of the year!

We Are Hiring

We are looking for remarkable individuals to join us in our quest to build the next-generation poker training ecosystem. If you are passionate, dedicated, and driven to excel, we want to hear from you. Join us in redefining how poker is being studied.