When To Just Shove Post Flop in ICM Spots

The general trend for bet sizing, when ICM is significant, is that it becomes smaller. We identified this several years ago, way before the GTO Wizard postflop ICM solver saw the light of day. Big bets become small bets, sometimes small bets become checks, and so on.

One of the primary purposes of the smaller bet is to put the opponent into a tough spot where they would otherwise have an easy fold because of the ICM pressure. It is not only to take down the pot for the smallest amount risked; it’s to make it harder for the opponent to fold.

There are, however, times when the solver prefers the complete opposite option: open-shoving the flop for two or three times the pot. This is a trend my colleague Dara O’Kearney and I coined “Min or All-in,” referring to the fact that the solver tends to bet small or shove, hardly ever anything in the middle.

Today, I am going to explore when we might be motivated to shove the flop when ICM is significant, even for three or four times the pot.

Rather than exploring the specific range matchups and board textures where open-shoving flop is a good idea, I am going to attempt to show why the solver elects to shove flop in the first place, to give a more holistic understanding of when to get out the big guns.

Final Table vs. Money Bubble

It would be tempting to pick out boards where there is typically a lot of overbetting to demonstrate this, but I have picked out an example where that is not the case. First of all, let’s look at a Chip EV solution.

- The blinds are 20bb effective, the LJ has open-raised and the BB has called.

- The flop is Q♦8♥7♦.

Chip EV

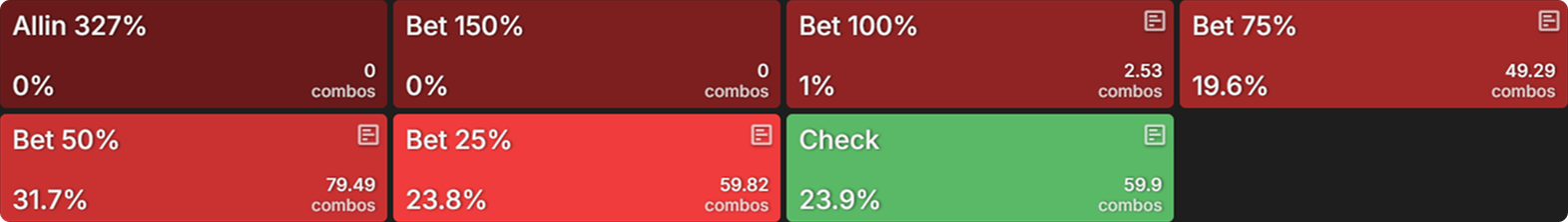

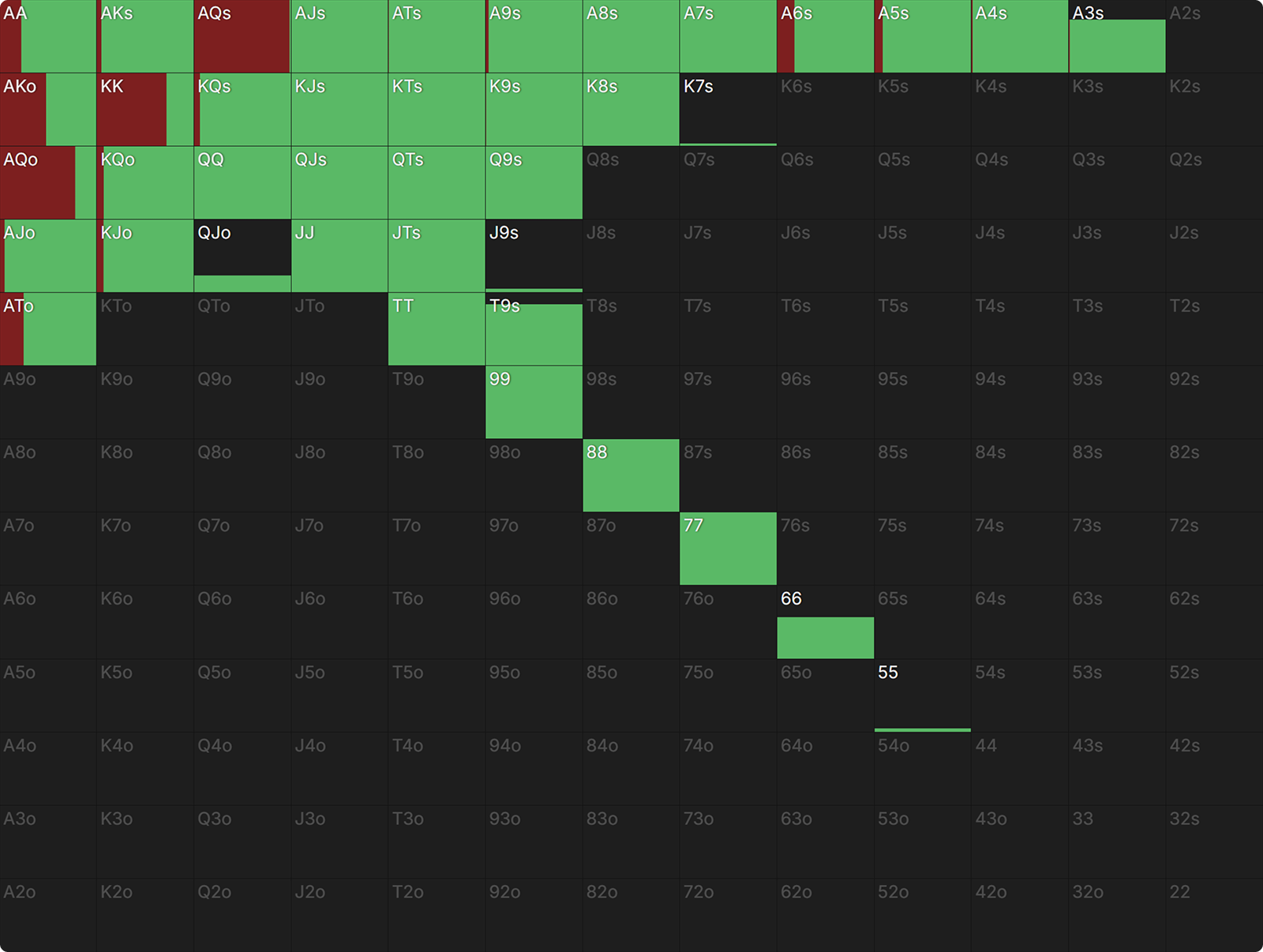

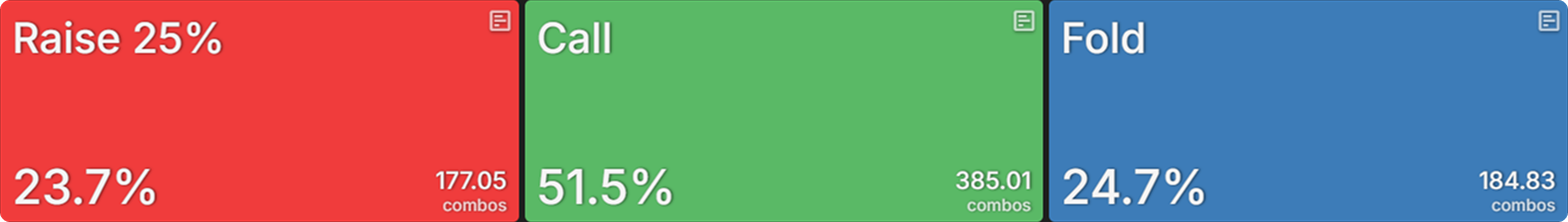

The BB checks 100% of the time, and this is how the LJ follows up:

There is a mix of actions, but practically speaking, the largest bet size used at a meaningful frequency is 75% pot.

I will be using the automatic bet sizing feature of GTO Wizard AI from now on. So for consistency, this is what the AI does for this same—still cEV—spot:

The hands that bet are largely the same, and the solver has settled on 47% pot when allowed one bet size. Very much a medium-sized bet.

Final Table

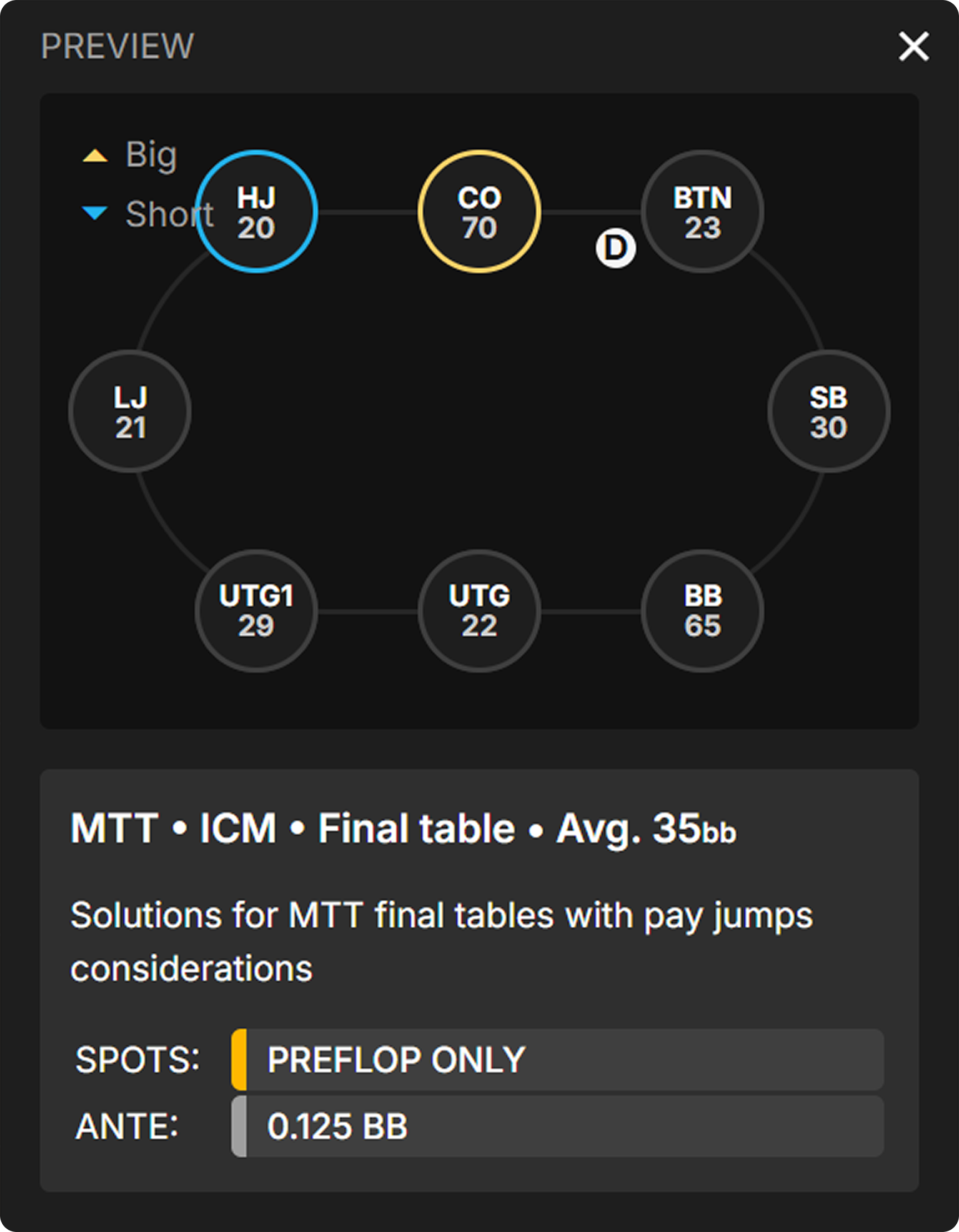

Rather than creating everything from scratch, I wanted to do something you could replicate practically, so I found a final table (FT) solution that is similar to this spot.

Here, the LJ has 21bb and the BB has 65bb, making the effective stacks 21bb. But don’t get tricked, the fact that the BB has a 3:1 chip lead over the LJ will influence the strategy

Diving into the postflop action, we get hit with a phenomenon unseen in the Chip EV environment: BB donks, despite this not being their board (with only 39.6% equity), which reflects how much ICM pressure is shaping strategy.

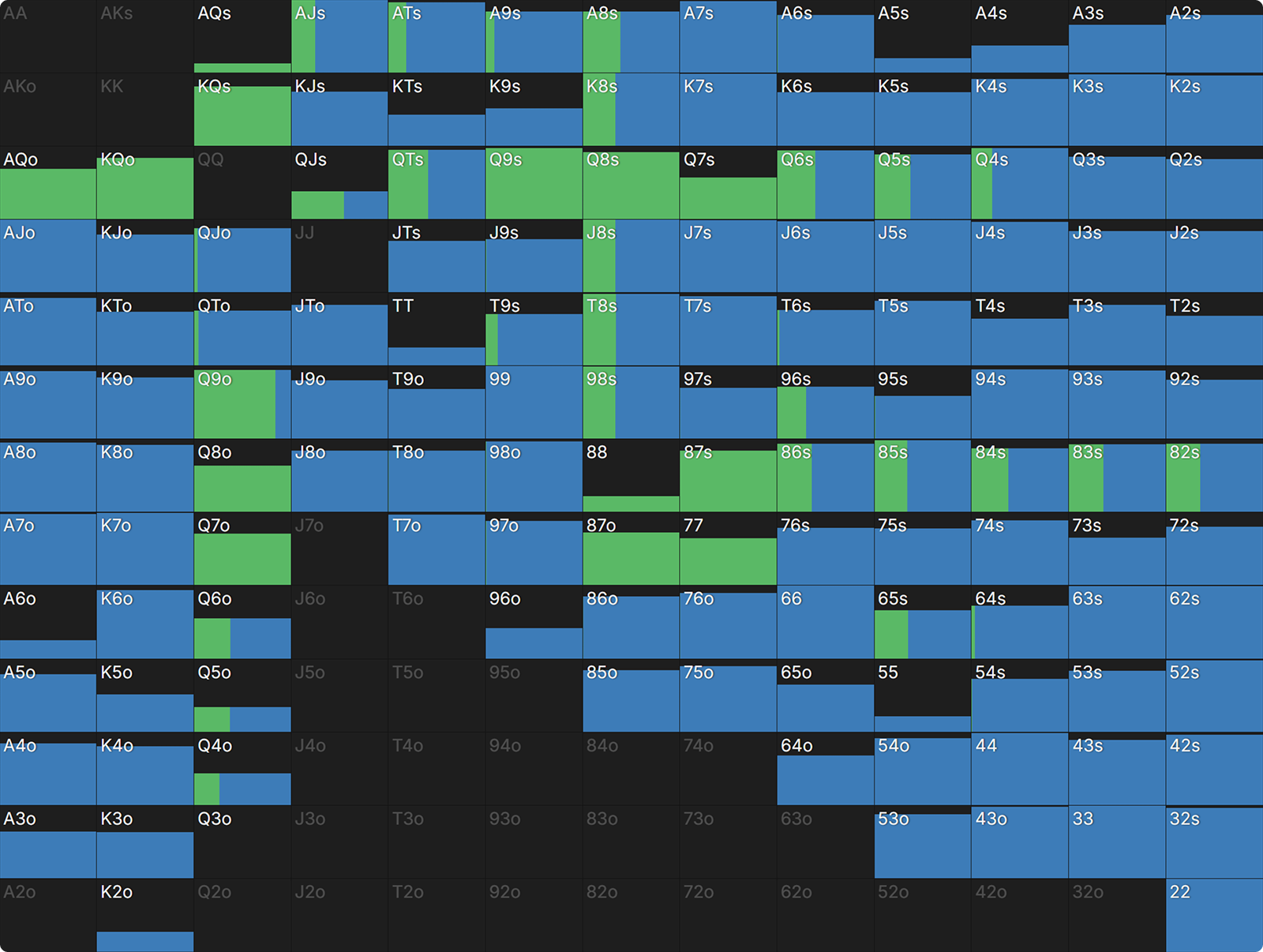

When the BB does check, this is what the LJ does in return:

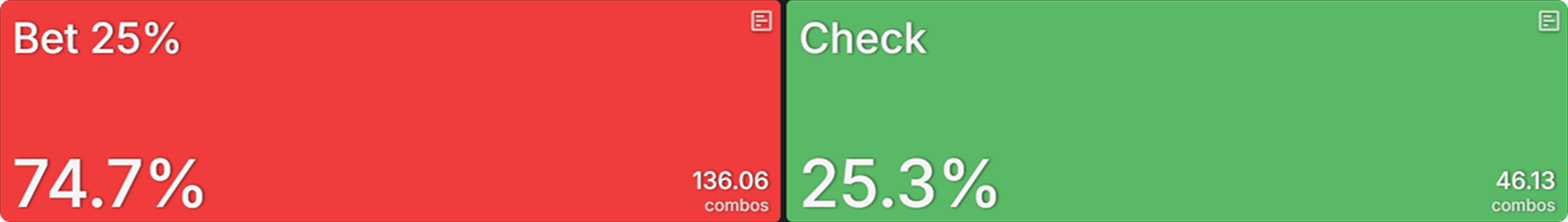

The strategy is not that different. Roughly the same number of hands and types of hands bet. The only drastic difference is that the bet size has decreased from 47% pot to 25% pot.

Money Bubble

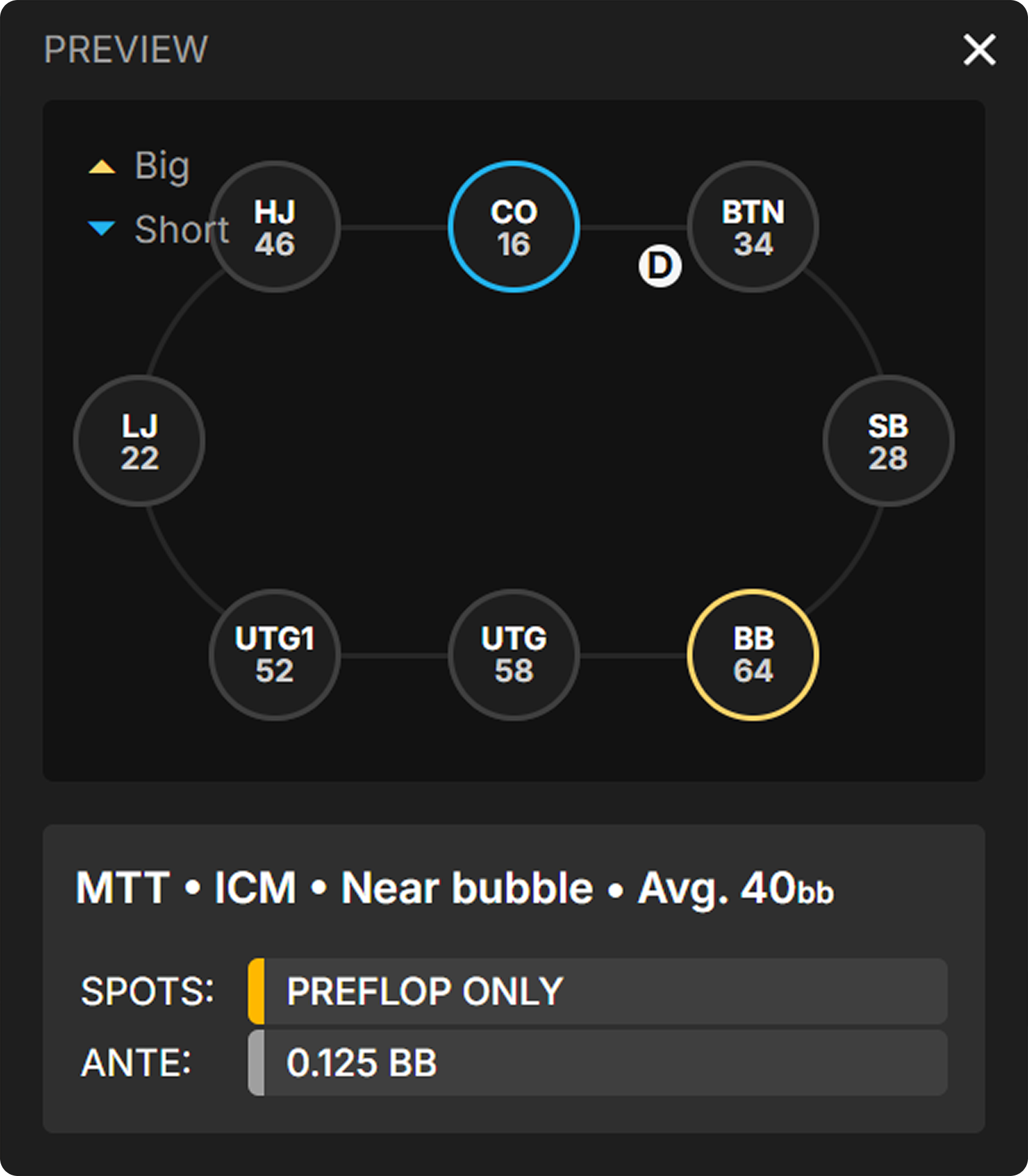

So far, no big surprises. Let’s look at a nearly identical spot but on the money bubble of a 200-runner tournament.

This time, the LJ has 22bb and the BB has 64bb, but I think we can all agree this is a very similar spot.

On that same Q♦8♥7♦ flop, there is leading again—a little bit more than last time:

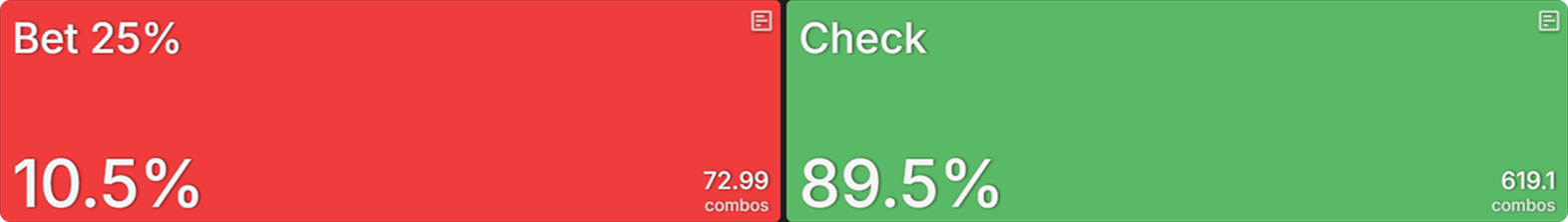

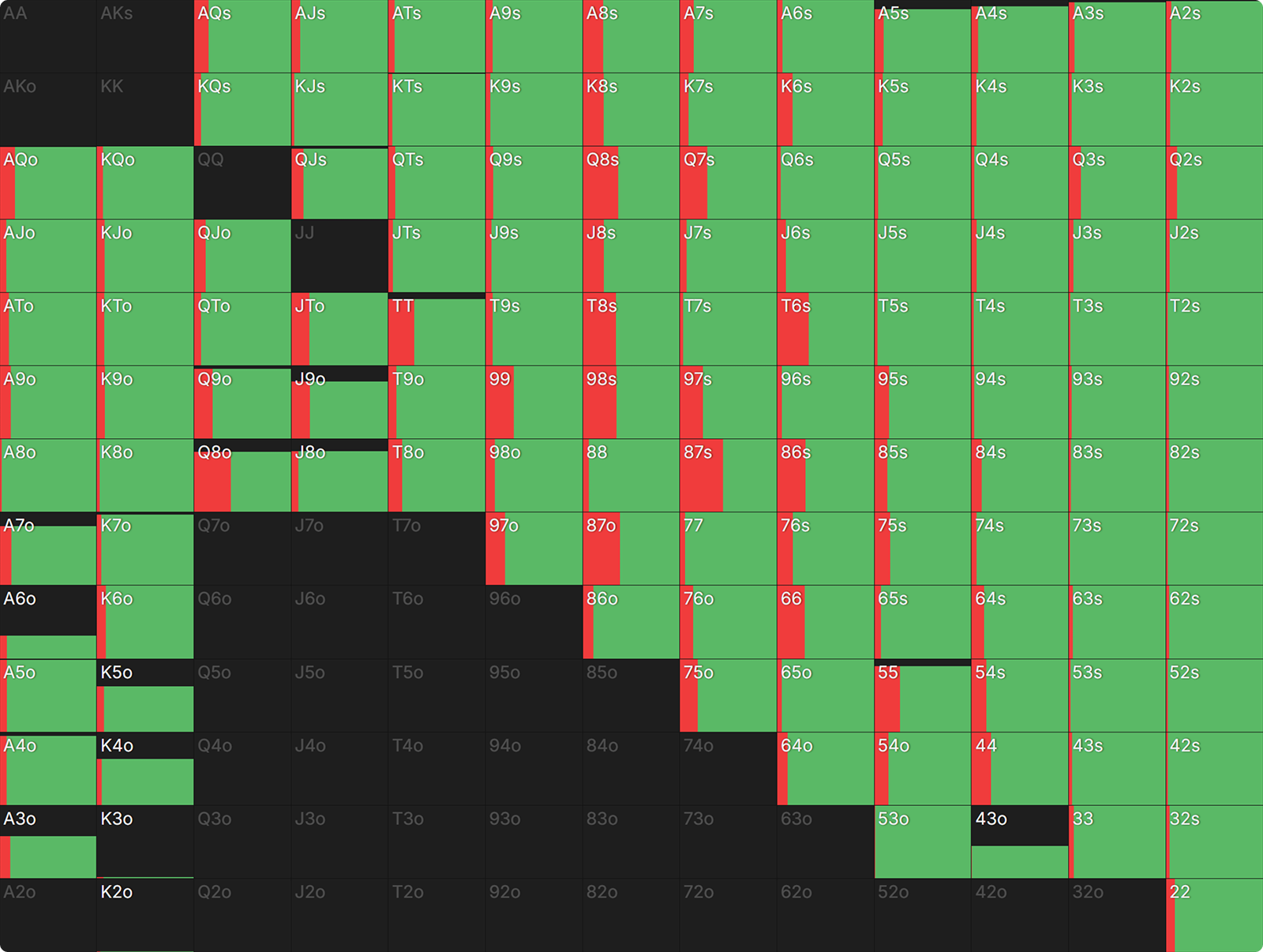

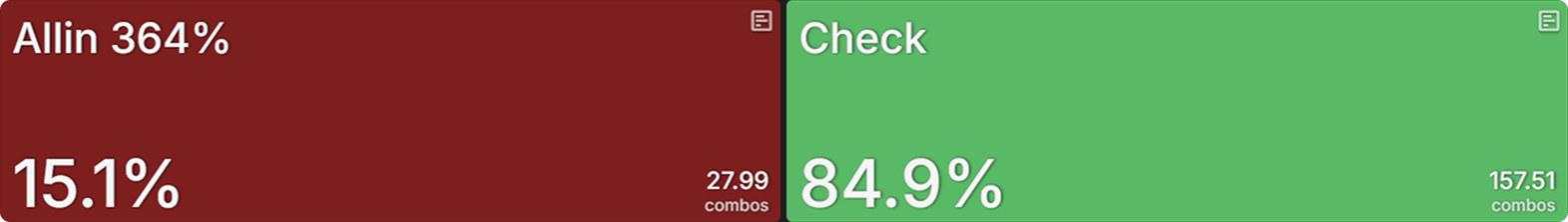

However, when checked to by the BB, this is what the LJ does:

The LJ has gone from checking ~25% of the time to checking ~85% of the time, which is already a massive difference. But when they do bet, they have gone from nudging in a 25% pot bet to pushing in the entire 20bb stack into a 5.5bb pot—almost a 400% pot-sized bet.

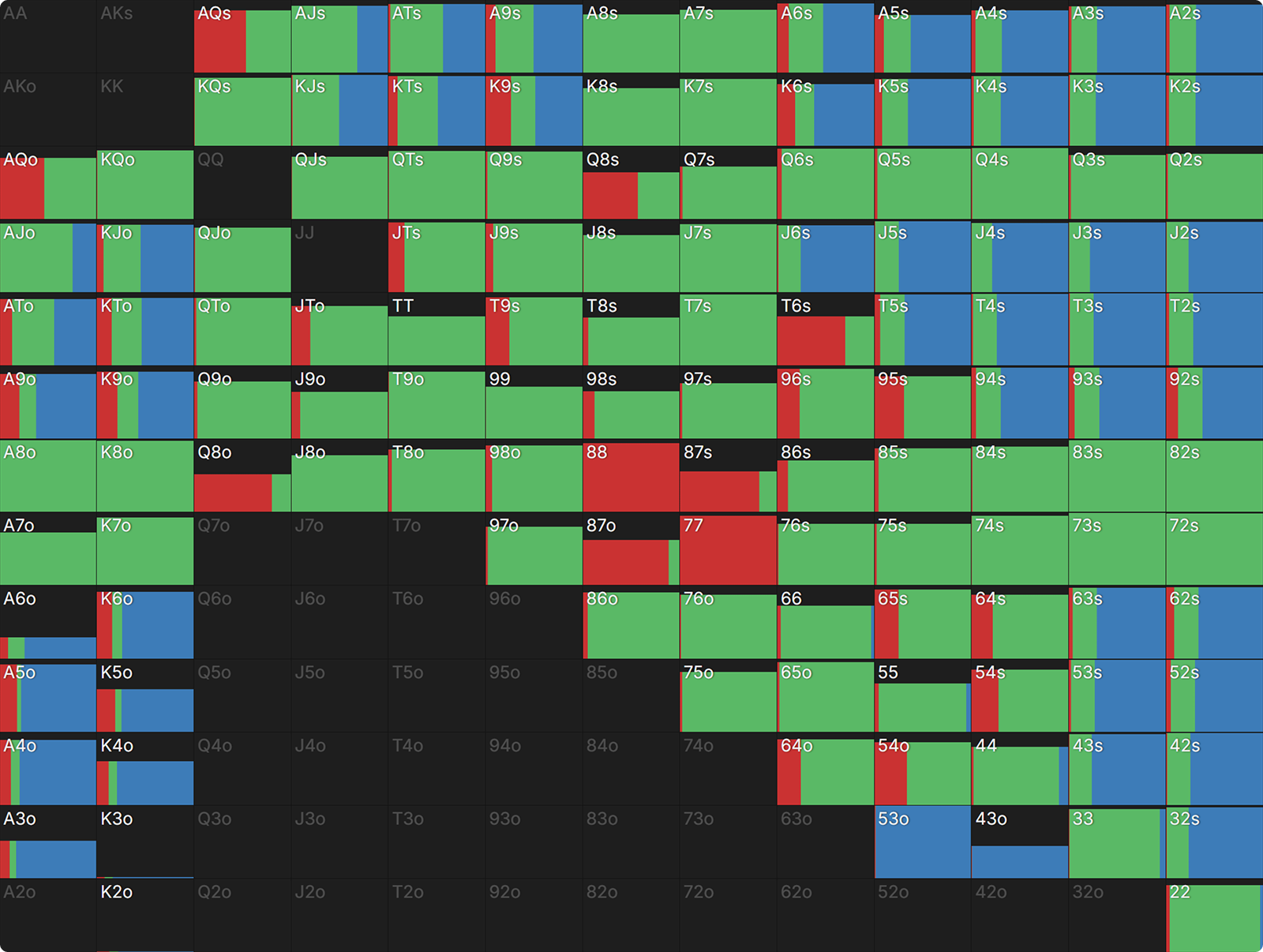

It’s a very narrow, polarized shoving range. The value range consists of AA/KK/AQ/KQ, which are all strong pairs that are usually best right now but hate a lot of turn cards, so they want to get the hand over with.

The bluffs I’d suggest are all hands that block continues more than they are semi-bluffs. This is the BB’s calling range:

Drilling down a little into the bluffs, a hand like A6s blocks pure calls like AQ/Q6s and also blocks mixed calls like 64s/65s. It also unblocks a lot of folds. Note that A6s never shoves when it’s of the suit of the flush draw.

Whether it is a value hand or a bluff, there appears to be a big incentive to end the hand as soon as possible to not to have to play turns and rivers.

Let’s rewind the hand and see what the response is from the LJ to the BB lead:

Obviously, now there are a lot of calls, but the hands in the shoving range are nearly identical to before. Again, the governing incentive for these holdings appears to be getting the hand over with ASAP.

Very strong made hands for the LJ (such as sets), mega draws like the nut flush draw, and combo draws like T♦9♦ all play passively—either by checking back or just calling a donk-bet. These holdings are understandably less concerned about protection, whereas the big pairs are super concerned about it.

The Value of Doubling Up

Why is it that the short stack plays differently on the money bubble vs. the final table?

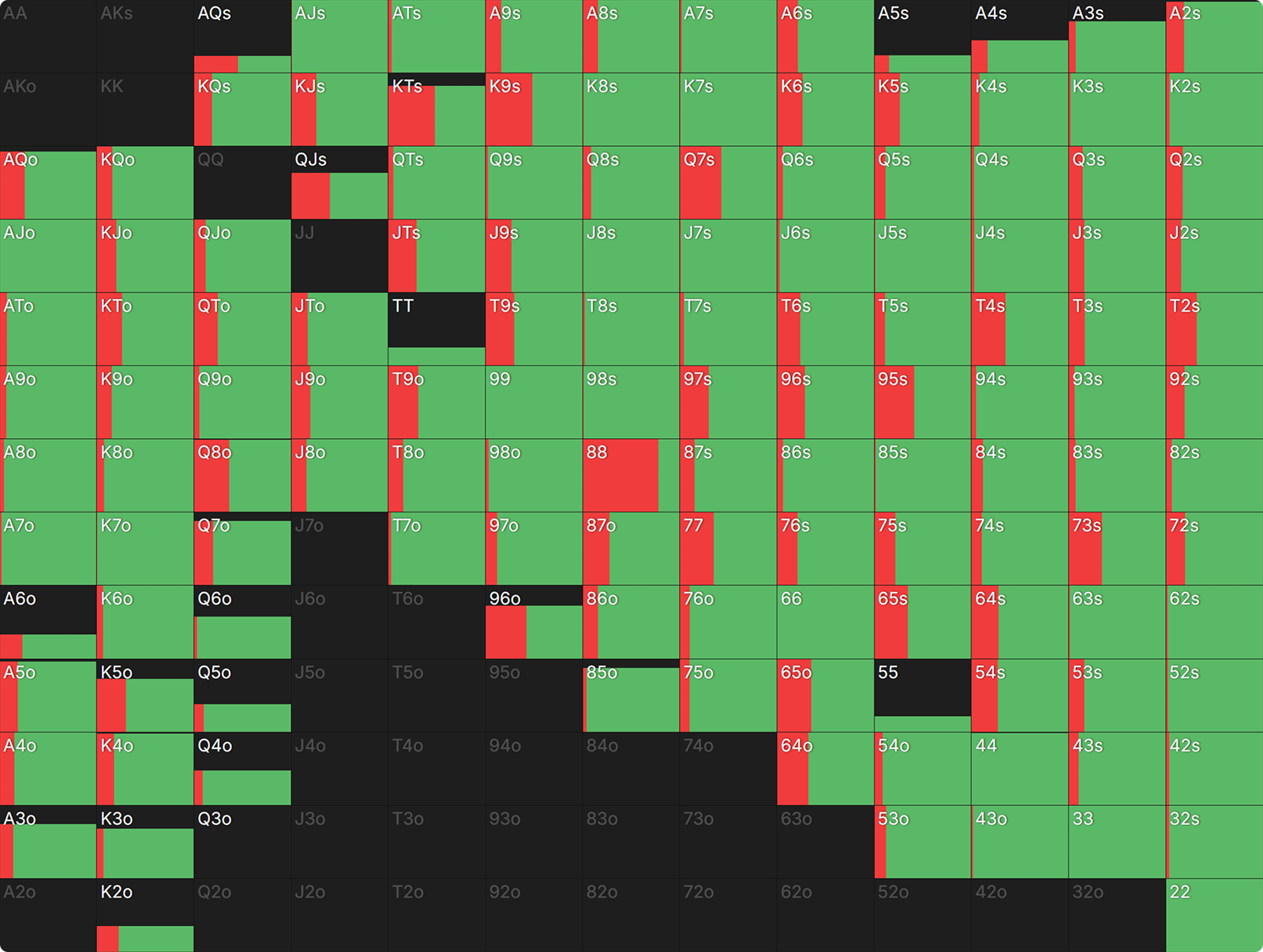

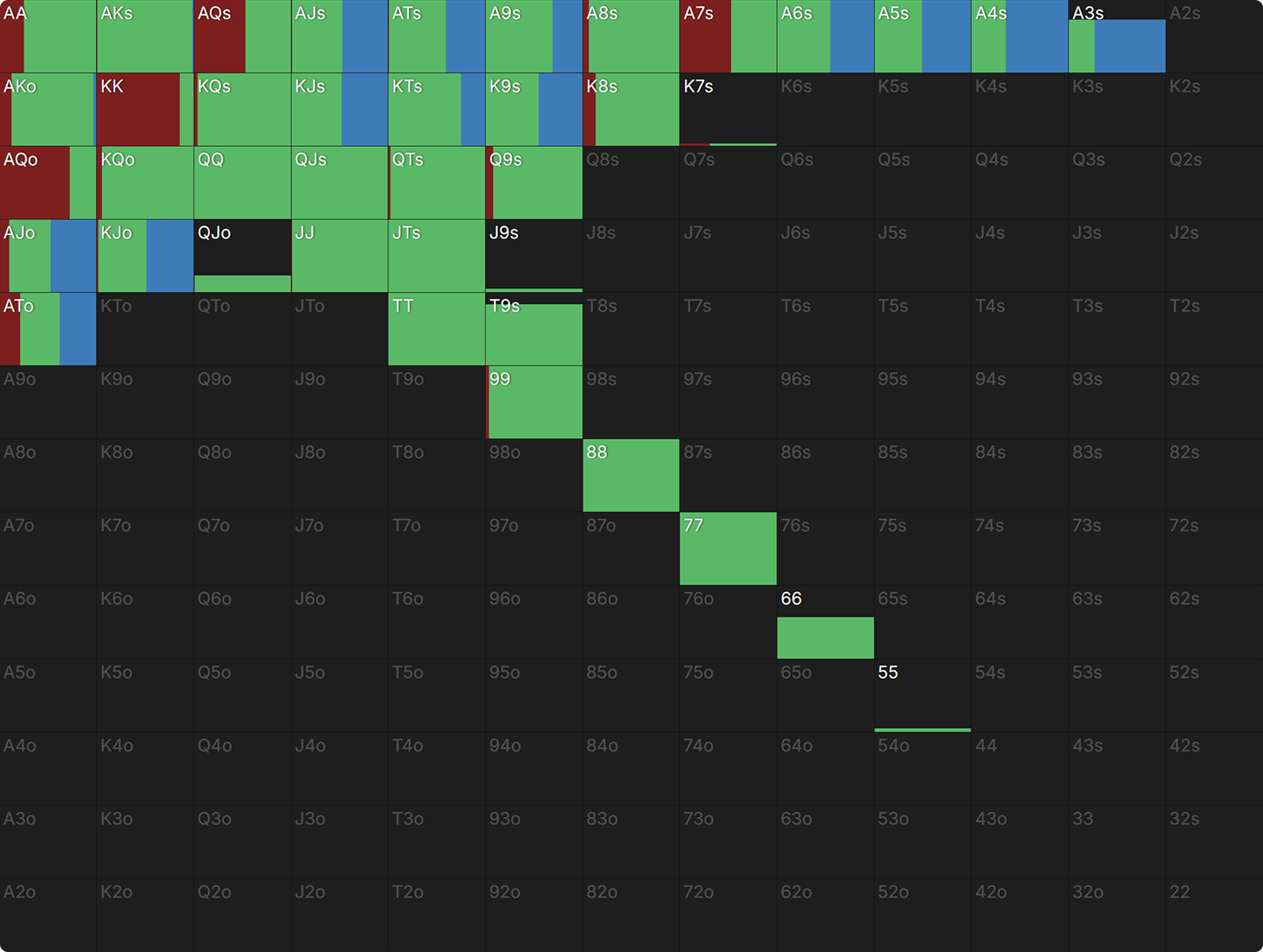

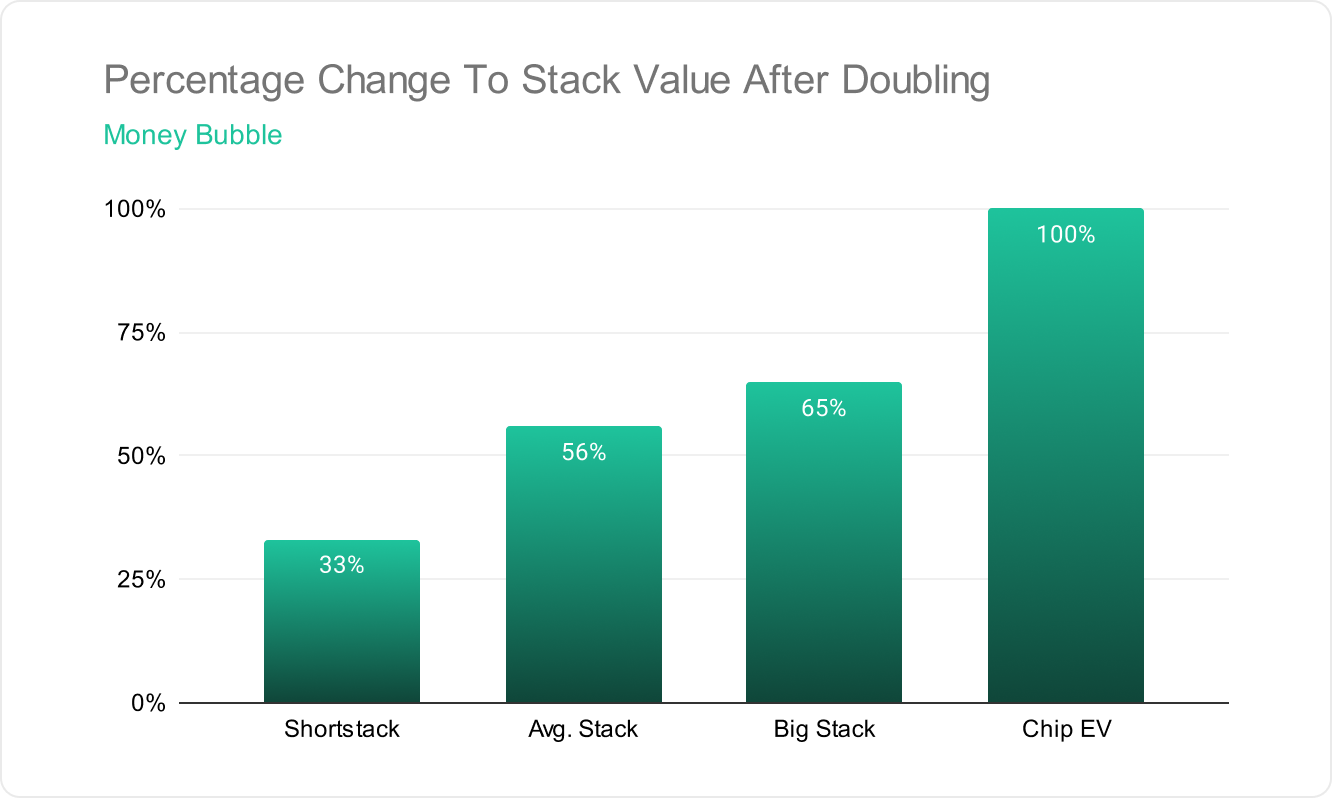

We explored this question in my article on the difference between the ITM-bubble and the FT-bubble. I won’t explore that in detail here, but to recap. On a money bubble, the short stack’s equity is tied up for the most part in the min-cash. In that article, we gave an example (see below) where a short stack doubled up but only saw their tournament equity ($EV) increase by 33.1%.

With the short stack having only a relatively small percentage of the total chips in play, doubling up does very little to improve their chances of making the final table to compete for the biggest prizes. In other words, the risk of losing $EV—mostly derived from the min-cash—outweighs the reward of gaining $EV—derived to a greater extent from payouts beyond the min-cash. So, their greater financial priority is to preserve their equity tied up in the min-cash.

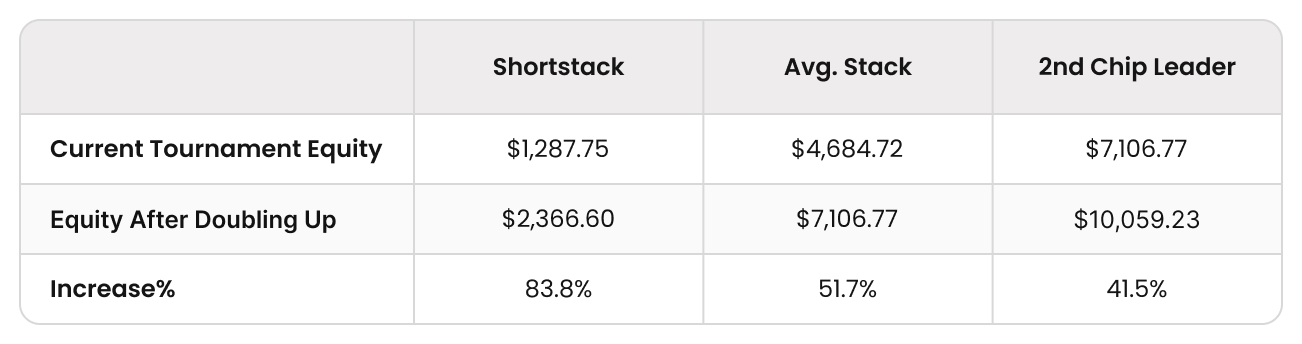

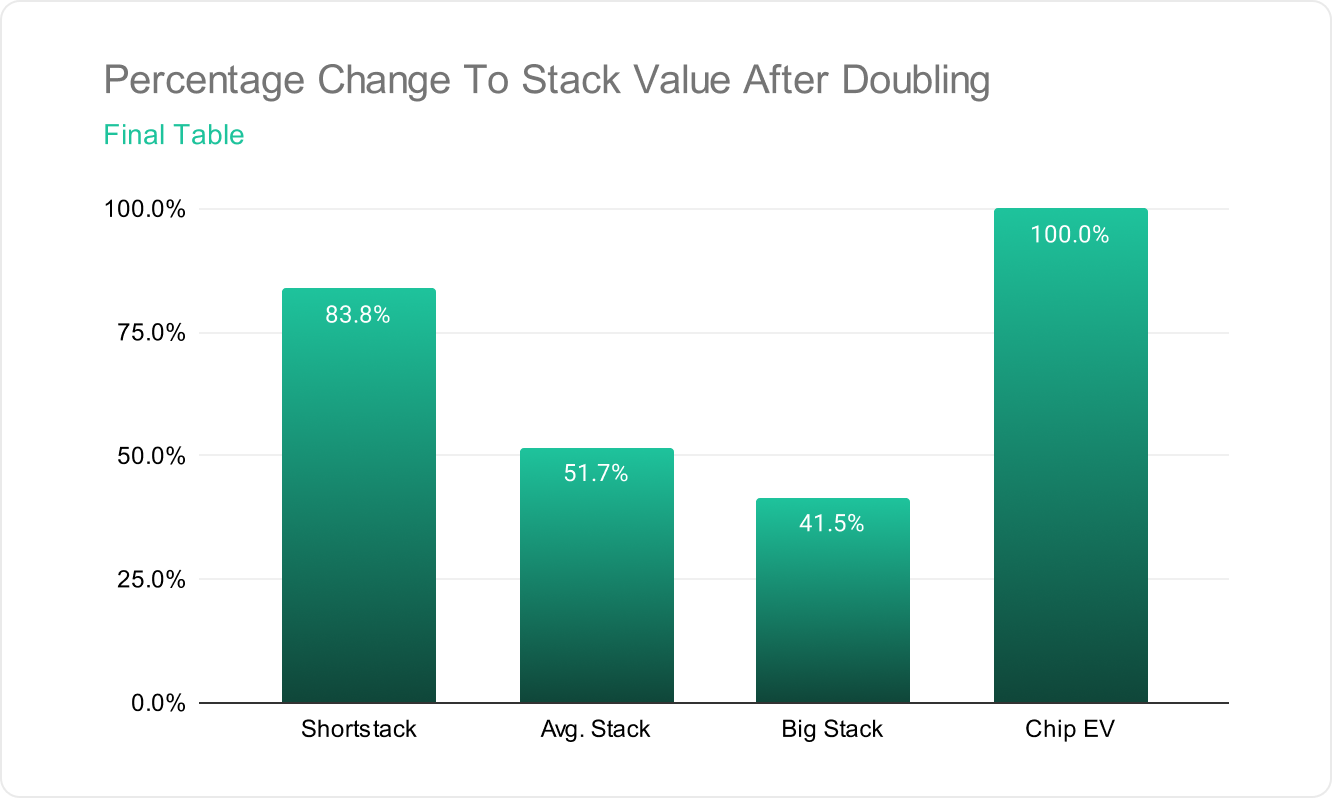

In the same article, on a final table bubble, the short stack increased their tournament equity by 83.8% when they doubled up:

The shorty may be short, but they are so much closer to the big prizes at the final table, so doubling is worth much more because there’s more $EV to derive from payouts beyond the min-cash.

OK, but why does this mean we open-shove the flop more as the short stack on the money bubble?

OK, but why does this mean we open-shove the flop more as the short stack on the money bubble?

It’s essentially because the upside of doubling is modest, and the downside of not doubling is catastrophic. To paraphrase Andrew Brokos with a quote of his I love from his podcast:

“We have chip equity and chair equity, and here, chair equity is worth much more than chip equity.”

There is much more value to surviving the hand than there is to risking your tournament life in an attempt to double up at this stage, given our situation. So, we take the most aggressive action we can. It may seem quite a wild strategy to open-shove the hands we do bet, but it’s actually a low-variance strategy because it should lead to many folds.

This is a reminder of a cardinal rule of ICM when ICM pressure is extreme:

The fewer chips you have, the more each one is worth.

What if We Ignore ICM Pressure?

Let’s conclude this discussion by examining what happens when we don’t open-shove with the above range. Instead, a strategy similar to the one on the final table is followed. This will be a common error amongst a lot of players who mistakenly assume that all ICM pressure is the same.

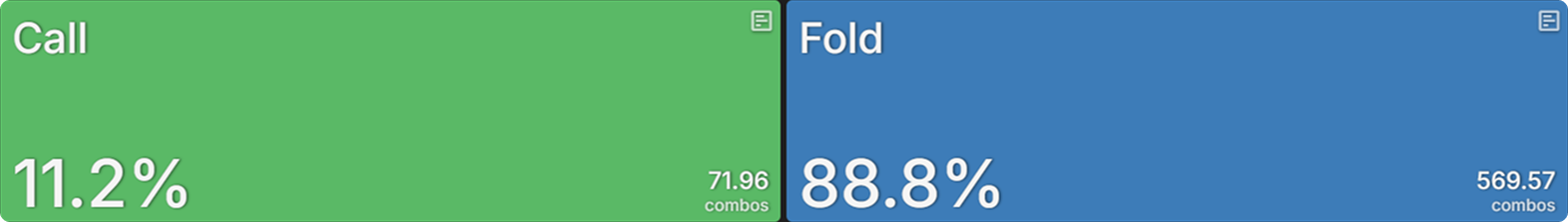

First of all, this is the BB response to the 25% pot bet at a final table:

This is the BB response to the same bet on a money bubble when we nodelock the LJ to use the same betting strategy as on the final table:

The BB more than doubles their check/raising frequency to pounce on the LJ. Their raise size has come down a little, which encourages the LJ to continue more often, which then puts them in a terrible position on subsequent streets.

I could go on, but it would be a whole other article exploring different runouts. I think you get the idea; making small bets on the bubble would lead to tough decisions on later streets.

Conclusion

The incentive to open-shove the flop tends to arise for a short-stacked player when they’re under severe ICM pressure, which is typically on the money bubble. This is because doubling our chips does not come anywhere close to doubling our tournament equity. As such, there is more benefit to surviving the hand because that would increase the chances of surviving the bubble, which is the top priority. For that purpose, a strategy that yields the most folds is best.

Medium- and big-stacked players, however, should not adopt this strategy because the value of doubling on the bubble is much greater for them than it is for short-stacked players.

The typical value hands that shove flop are the best pairs (including overpairs). Hands that are usually ahead of the hands that call, but not so much as the board runs out.

Therefore, the typical boards where we see open-shoving are dynamic boards with lots of draws and overcards. You won’t see this happen so much on paired boards, monotone boards, or Ace-high boards, where the top end of the aggressor’s range typically stays ahead on subsequent streets.

Open-shoving the flop may feel like a ‘scared money’ strategy, but on the bubble as a short stack, that is perhaps the right mindset to have.

Author

Barry Carter

Barry Carter has been a poker writer for 16 years. He is the co-author of six poker books, including The Mental Game of Poker, Endgame Poker Strategy: The ICM Book, and GTO Poker Simplified.

Wizards, you don’t want to miss out on ‘Daily Dose of GTO,’ it’s the most valuable freeroll of the year!

We Are Hiring

We are looking for remarkable individuals to join us in our quest to build the next-generation poker training ecosystem. If you are passionate, dedicated, and driven to excel, we want to hear from you. Join us in redefining how poker is being studied.