A Comprehensive Guide to Playing Satelites

One of the most important inventions in poker that contributed to the growth of the game was the satellite tournament. This is a tournament where the prizes are tickets to a larger buy-in tournament. If it weren’t for satellites, hopeful amateur players would not be able to participate in events like the World Series of Poker Main Event. Satellites have massively improved tournament liquidity, made events softer, and helped create viral ‘Cinderella stories’ of amateurs winning big, most notably Chris Moneymaker’s 2003 Main Event win.

The fundamental difference between satellites and other tournament formats is that all prizes are of equal value. If you are playing to win a $1,000 ticket, the player who finishes with the most chips wins a $1,000 ticket, and the player who survives the bubble with an ante also wins a $1,000 ticket. There are no extra prizes, and thus, no incentive for building the biggest stack.

This will often warp the strategy beyond anything else recognizable in tournament poker.

ICM is most extreme on satellite bubbles, compared to any other poker format.

And so, it is often correct to fold the (preflop) nuts in a satellite. It is valuable to understand the game theory concept of mutually assured destruction in relation to satellites. It is often the case that two players have nothing to gain from taking each other on near the end of a satellite because it could spell disaster for them when they likely could fold their way to a seat.

What follows is a primer on satellites where two or more seats are on offer. This does not include ‘winner-take-all’ satellites. As there is only one prize in those, they are essentially tournaments that should be played as a cash game: Chip EV. This also does not include the new format of ‘milestone’ satellites, where seats are awarded when a certain chip threshold has been reached.

Types of Satellites

Before we delve into the strategy, here is a quick note on the various types of satellites on offer. Some satellites are ‘must play’ which means you are automatically registered for the target tournament. In some instances, you can win multiple tickets and take the subsequent ones as cash.

There are also more flexible satellites where you win a ticket for an event, which can be used at any time. You might win a $109 ticket which can be used for any $109 event in the poker client, or it might be specifically for the $109 Sunday Million, but you can choose when to use it. Tickets often have expiry dates on them to force the winner to put the liquidity back into the ecosystem sooner.

The most flexible form of satellite is the T$ satellite, where you win tournament money rather than a prize. This means you can use the T-dollars for any tournament (including other satellites) and break it up between different buy-in levels.

The type of satellite on offer is important to know.

The more flexible the prizes of satellites, the more tough regulars they attract because satellites can be profitable in and of themselves.

And conversely, the more limited they are, the more amateurs will be in them, trying to qualify for a specific (often, bucket list) event.

How Different Is the Strategy?

Let’s fast forward to the end of a satellite to give you an impression of how different they are from other formats.

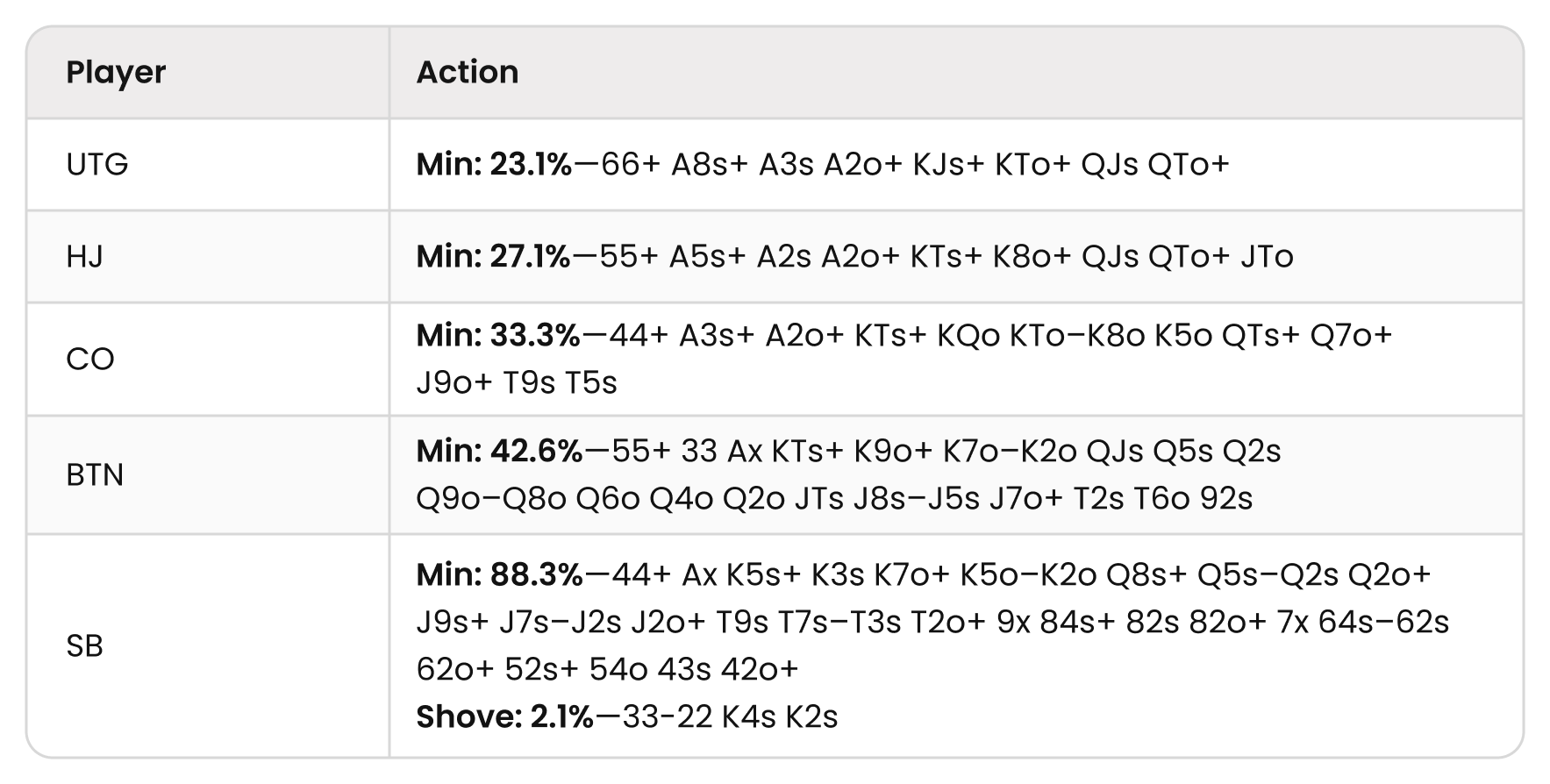

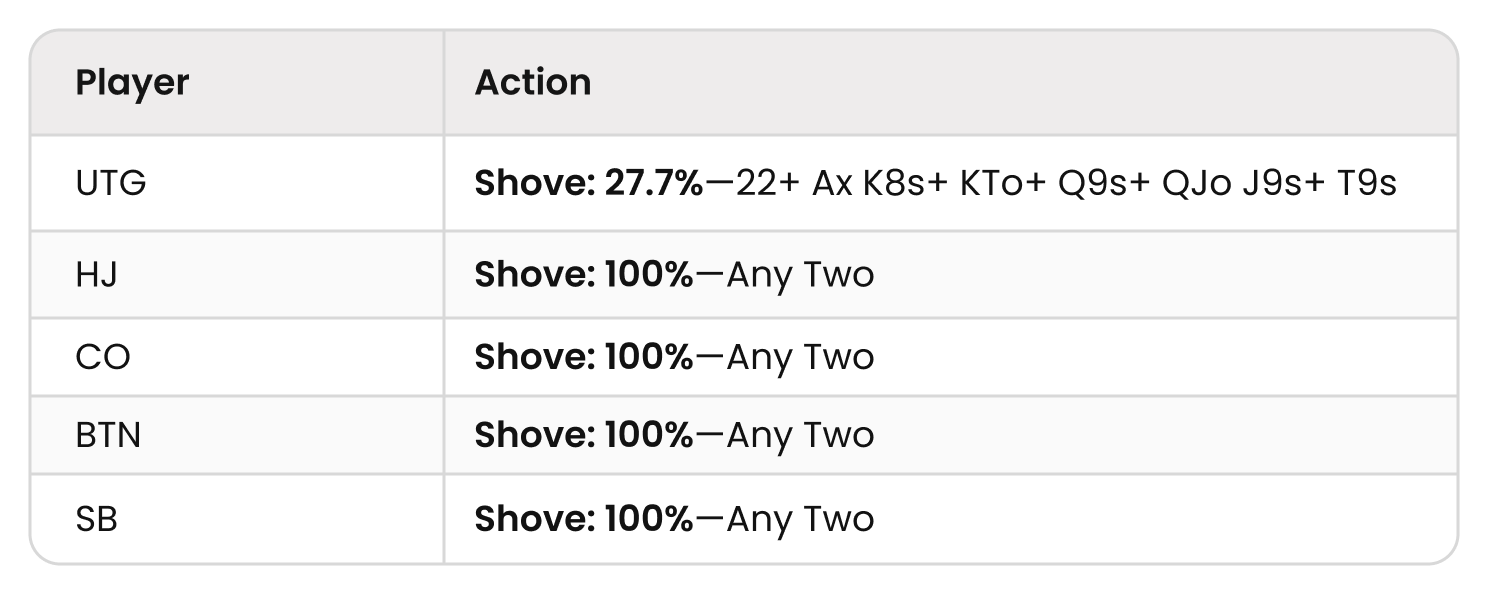

In the following example, 6 players remain with 20bb each. We are going to first look at opening ranges. These are the Raise First In (RFI) ranges for each player (when the action is folded to them).

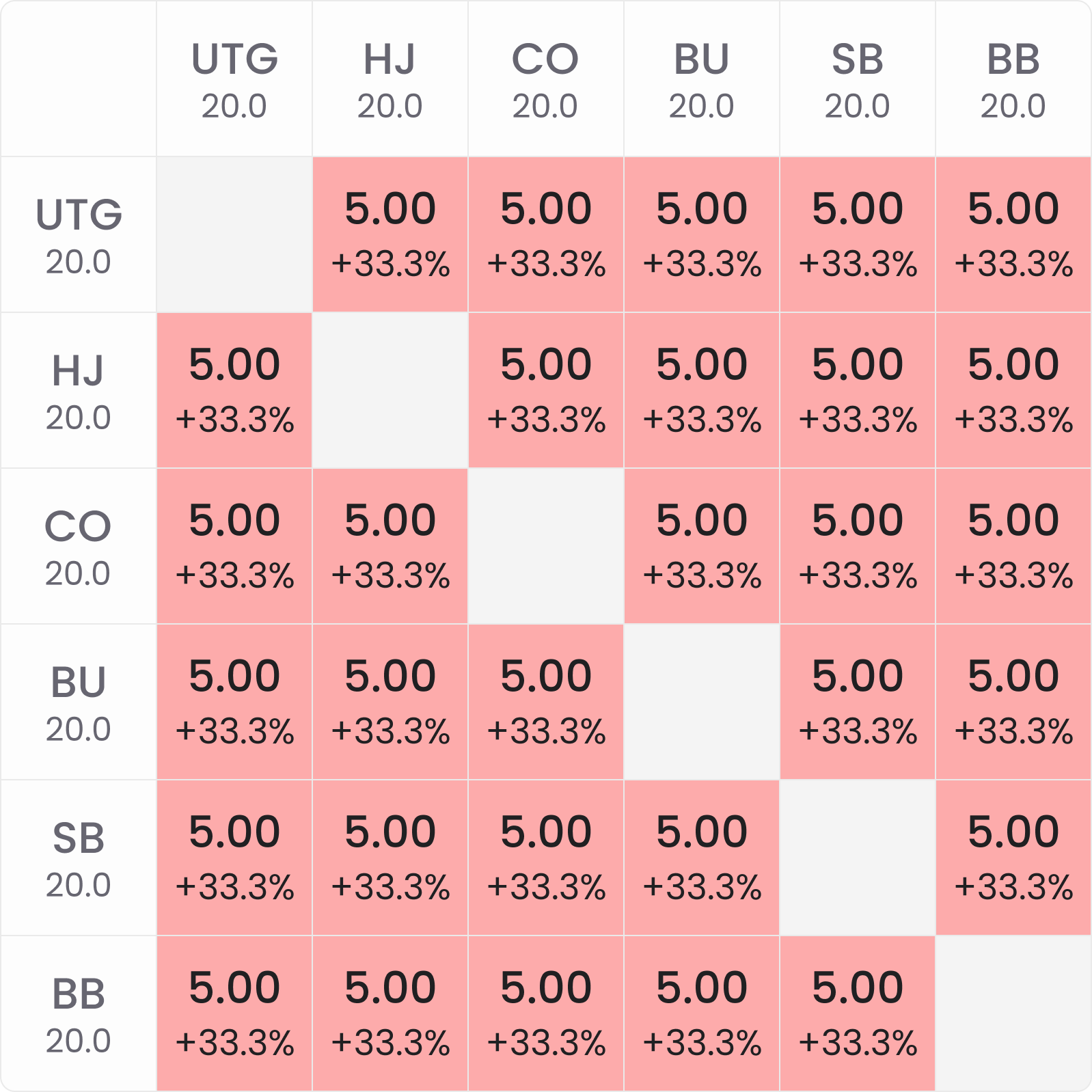

All of these examples were produced using HoldemResources Calculator. Consider them very much a toy game example. The players were given the options to shove or min-raise. Rather than show you the usual range grids, I thought it was easier to follow the differences in strategy for the whole table by displaying the ranges as text. There is some strange solver noise around the edges of some of these ranges; ignore that and pay attention to the broad strategic divergences.

Stacks: 20 – 20 – 20 – 20 – 20 – 20

First, let’s look at a Chip EV example:

Now, let’s look at the same spot, but in terms of $EV (money bubble) of a tournament with a standard payout structure:

Understandably, the ranges are much tighter, and shoving has become an option. The SB is wider because they only have one player to get through and that player must call off tighter.

Now let’s look at the same spot but with $EV (satellite bubble):

This may surprise a lot of you, even those familiar with satellite strategy.

First of all, practically speaking, the only option is to shove. AA does get opened for the minimum, but in practice, that should probably be a shove too. We shove the whole range to exert maximum ICM pressure on our opponent. We do not want to open, get shoved on, and find ourselves in the ICM coffin. It’s not uncommon to see shoving become the optimal strategy for most hands with 30bb stacks late on in a satellite.

Notice that some of the ranges are identical, regardless of position. I suspected this was a bit of solver noise, but this does hold true, particularly with calling ranges, as we will see shortly.

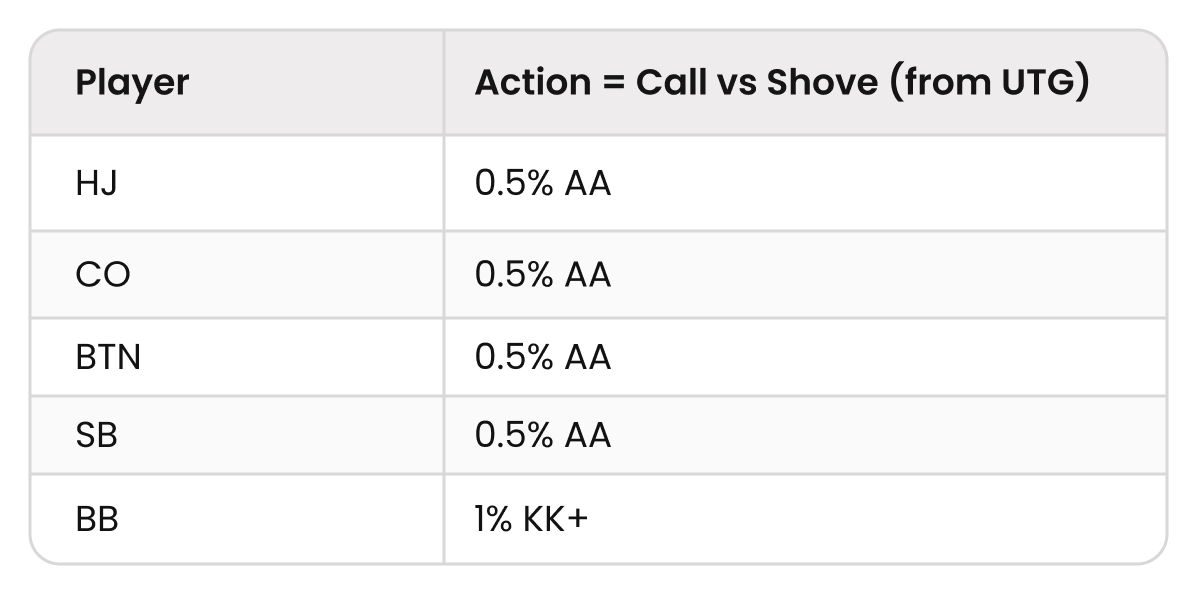

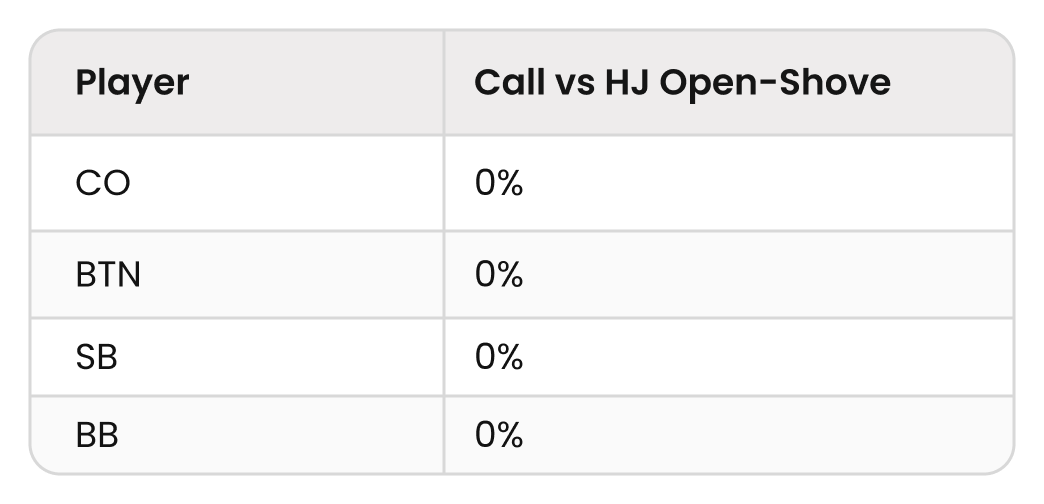

Finally, the ranges are much wider. In fact, it is almost 100% of hands! This goes against a lot of players’ instincts when we think of satellites. To see why this is, let’s look at the calling ranges for a UTG shove:

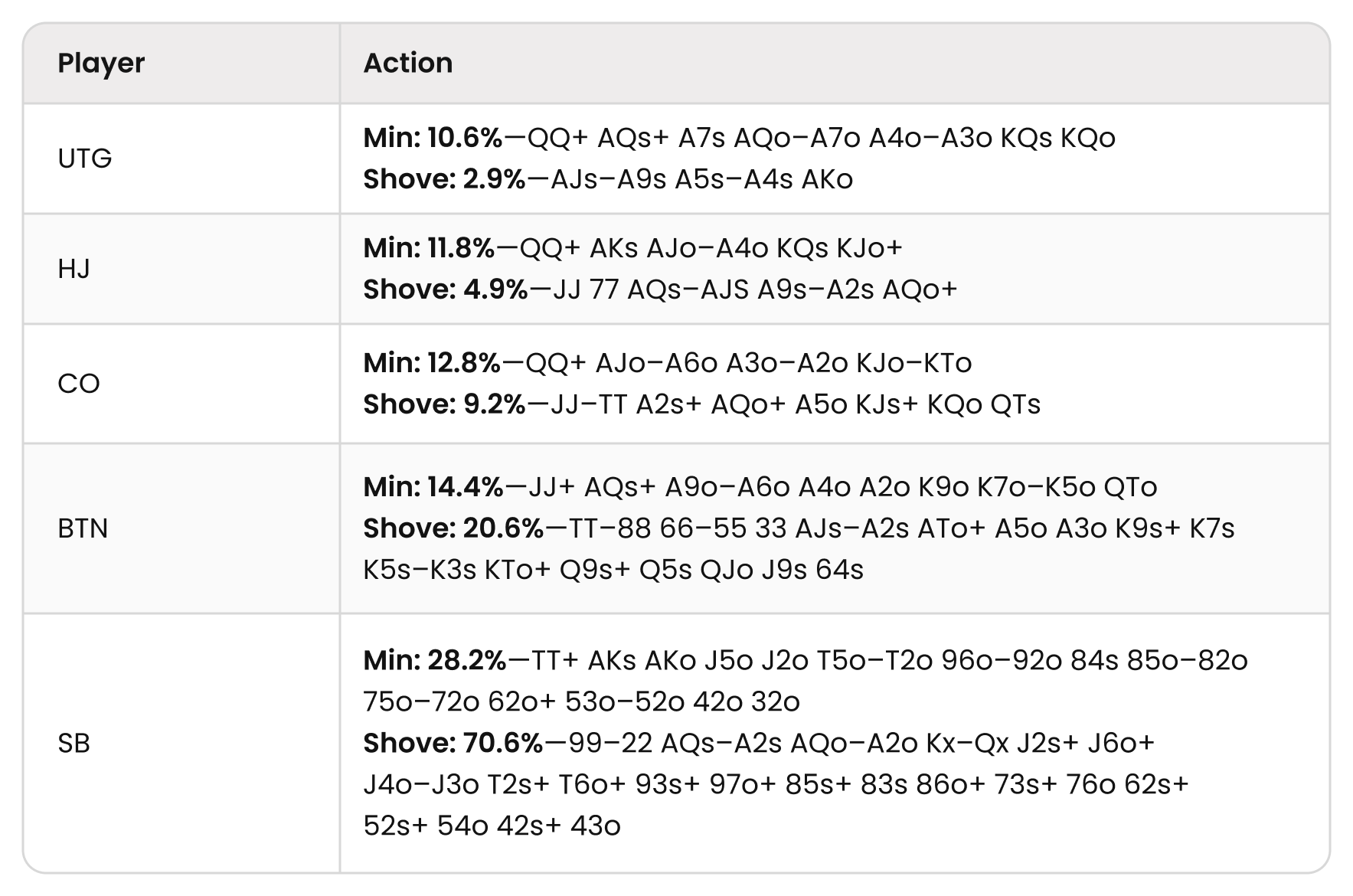

The only hand anyone can call with is AA, other than the BB, who gets to call with KK too, because they also close the action.

These are the bubble factors for this spot:

Everyone has equal stacks in this toy game, and therefore, everyone has the same bubble factor (of 5). This means they need 83.3% equity before factoring in pot odds to justify putting their stack in the middle.

Most people know that satellites involve tight folds, but often overlook that this also implies loose shoves.

This assumes that all the satellite grinders at the table are playing game theory optimal. Most will not be, but most do understand they need to be much tighter.

Deviating From Equilibrium

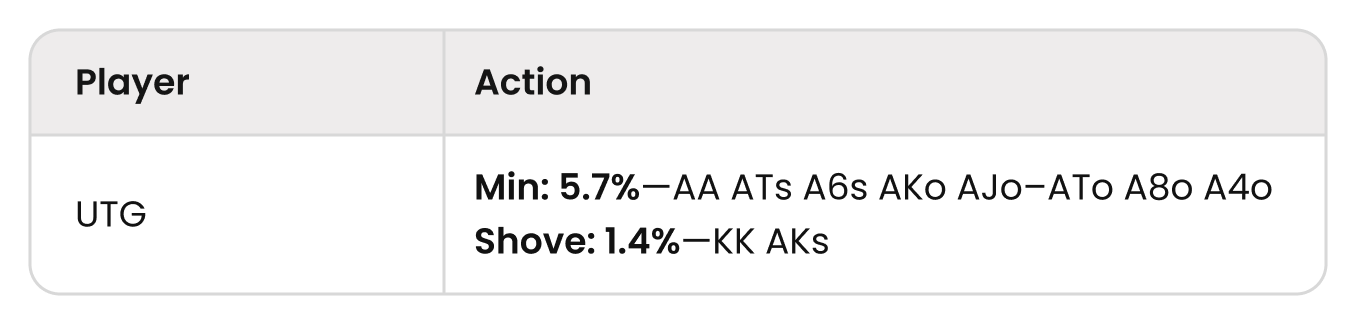

Let’s see what happens when BB deviates by slightly widening their calling range so that they call with JJ+ and AK, which doesn’t seem like such a huge mistake. This is the new UTG range:

A minor adjustment in the calling range has resulted in a dramatic adjustment in the opening range. UTG only shoves 1.4% of hands and has opted to min-open the rest of the range, which, as you will notice, is exclusively Ace-x oriented.

UTG has gone from opening almost everything (93.3%) to opening just 7.1% of hands. The only hand that doesn’t include an Ace is KK.

To be perfectly clear, UTG does not want to be called. The only reason they shoved previously was because of how frequently it would get through. This is the mutually assured destruction we alluded to. They can shove so wide because nobody wants to call for their satellite life and risk elimination. But when the calling range widens just a pip, UTG tones down the aggression because they do not want to expose themselves to that (increased) risk.

This highlights 3 important lessons for satellites:

- Fold equity is the most important form of equity

- Avoid any situation with an all-in and a call

- Blockers go up in value

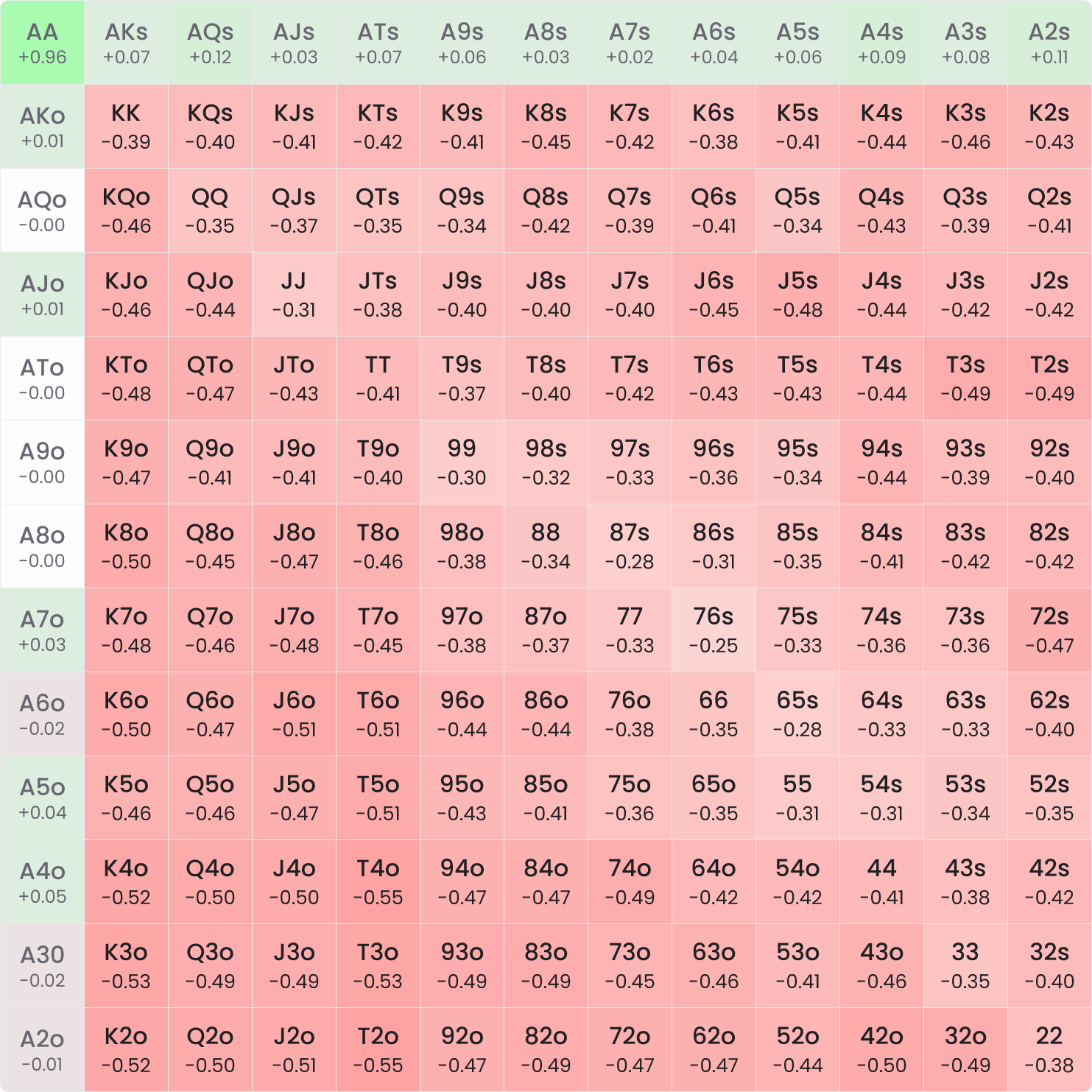

As we saw, the only hand class in the adjusted UTG opening range was Ace-x. Let’s see what the HJ does when UTG opens. I’ll present the range in the usual hand grid this time for effect. These are all reshoves:

A stark example of the importance of blockers. Spoiler alert: the only hand UTG can call with is AA. As such, the HJ can shove any Ace-x hand because it blocks AA (as well as shoving AA for value).

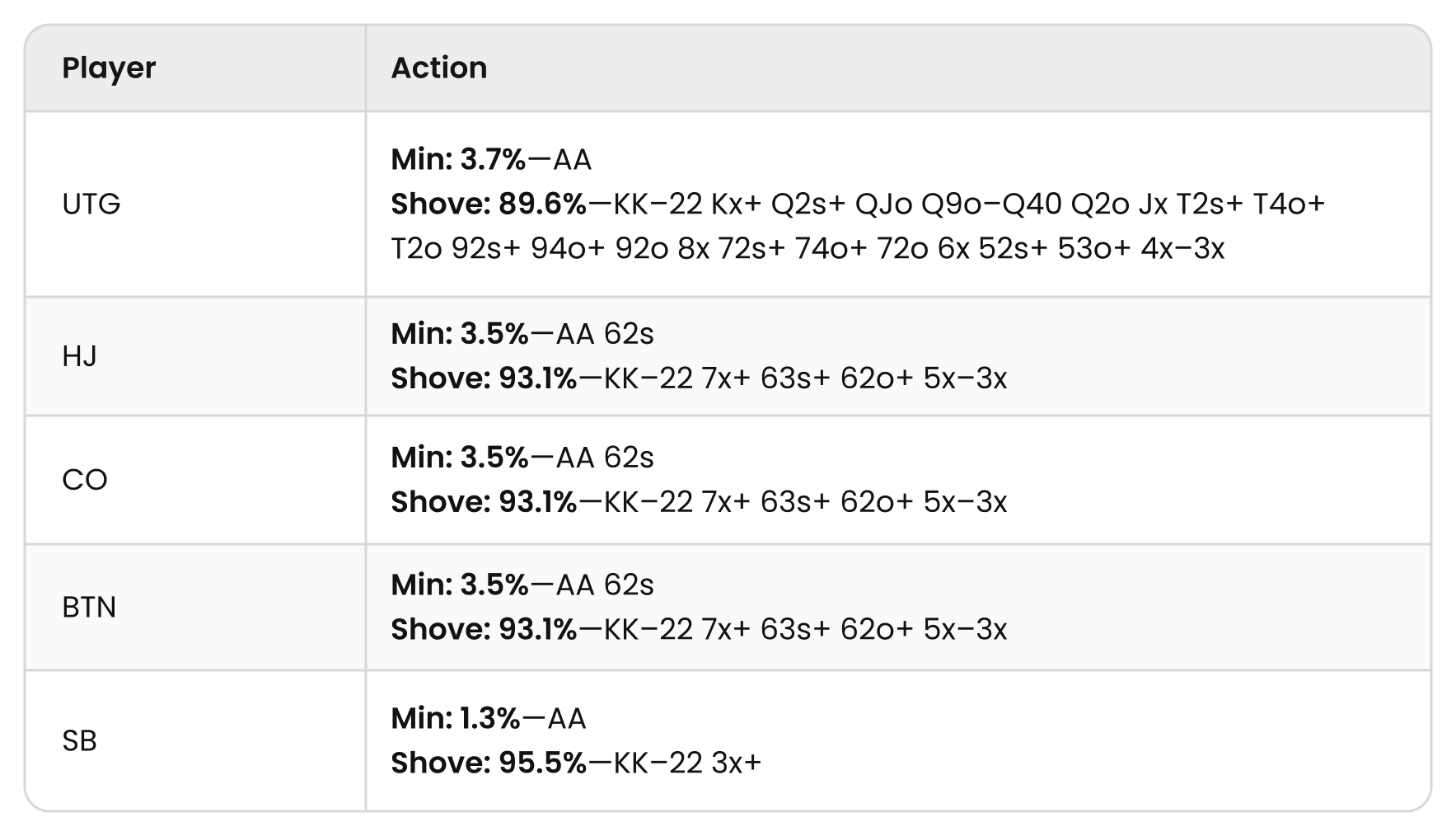

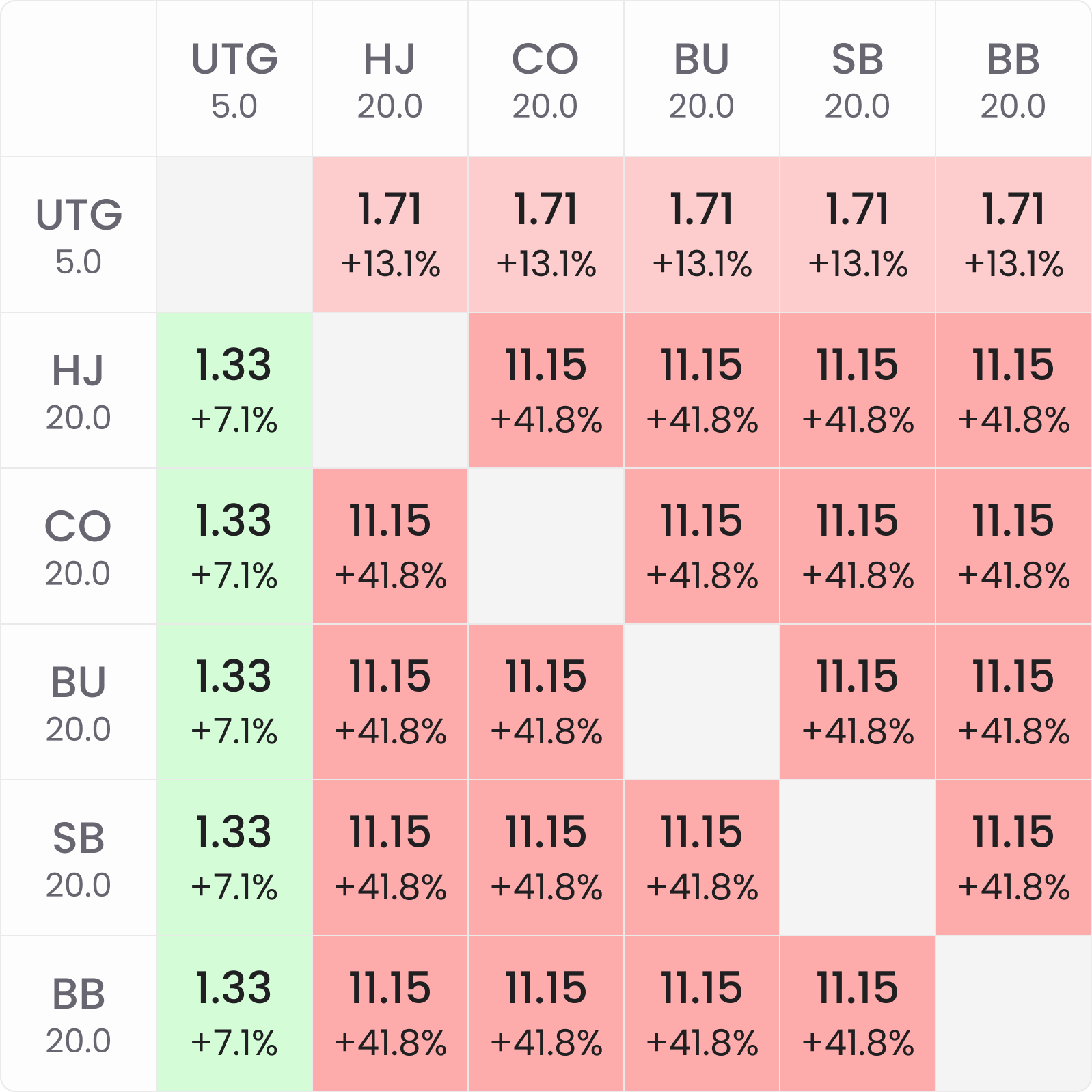

Stacks: 5 – 20 – 20 – 20 – 20 – 20

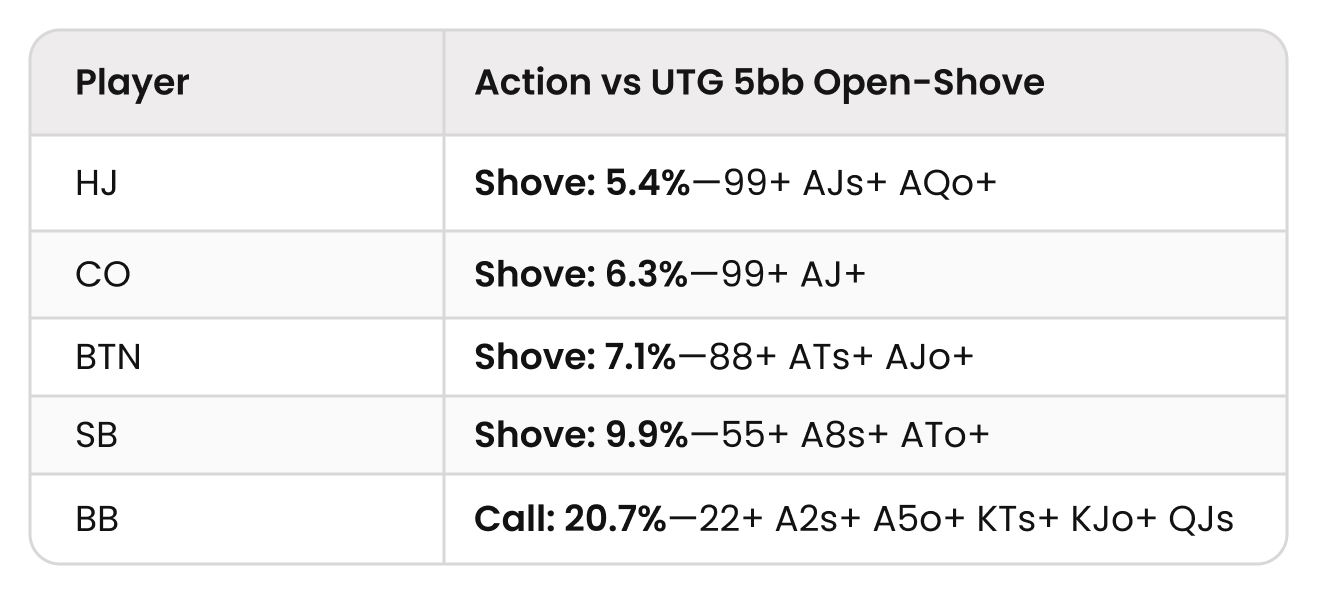

Let’s make one tweak: revert everything to what it was before, but we will give UTG a stack of 5bb, everyone else still has 20bb. These are the new opening ranges:

Let’s jump to the case where UTG folds and the HJ shoves. These are the calling ranges:

As you will likely have guessed ahead of time, this is a fold AA situation. We can see why with the bubble factors:

Everyone apart from the short stack, currently in the UTG seat, has a bubble factor of 11.15, meaning they need 91.8% equity before factoring in pot odds to profitably stack off. No hand, not even AA, has that much equity preflop!

For completeness, let’s look at the response to the UTG shove, which is just 5bb:

It might surprise you that the shoving/calling ranges are quite wide, given that each player left to act could still eliminate the shover.

Why can, for example, the HJ get it in with 99 or AJ when the BB could wake up with AA and potentially bust them?

This is for two reasons.

- Anyone acting after the reshove has to call either AA or KK.

- Most of the time, if a third player calls and wins, UTG will be eliminated too, and be the bubble boy/girl because they had the shorter stack. If UTG beats the HJ but not the BB, they still bubble. So, the only bad situation for the HJ would be if they get called by the BB when UTG has the best hand, and the BB has the second-best hand. Given how rare the BB calls to begin with, this is not much of a concern.

When To Fold Aces Preflop

As we have seen, there are spots in satellites where we should fold AA preflop. This is because there will be times when we need more than, say, 85% equity to call and AA does not have that against most ranges.

There are a few ways to intuit these ‘fold everything’ spots. First of all, by estimating the stack you need to beat the bubble.

Let’s say that 1-in-10 players win a ticket and the starting stacks are 10,000. That means that the average stack after the bubble will be 100,000. If you get this amount by the bubble, it means that, most likely, there will be players who will be forced all-in before you. In reality, the spread of stacks will be much wider, and several micro stacks might be poised to bust before you are ever threatened.

If you get to the average stack after the bubble or close to it, and the spread of stacks is wide, you should probably start to think about turtling up and folding everything when shoved upon.

A secondary benchmark—precisely available in online poker—relates to your relative position in the field. It goes like this:

If you are inside the bubble by more positions than there are players outside the bubble, you usually have a seat locked up.

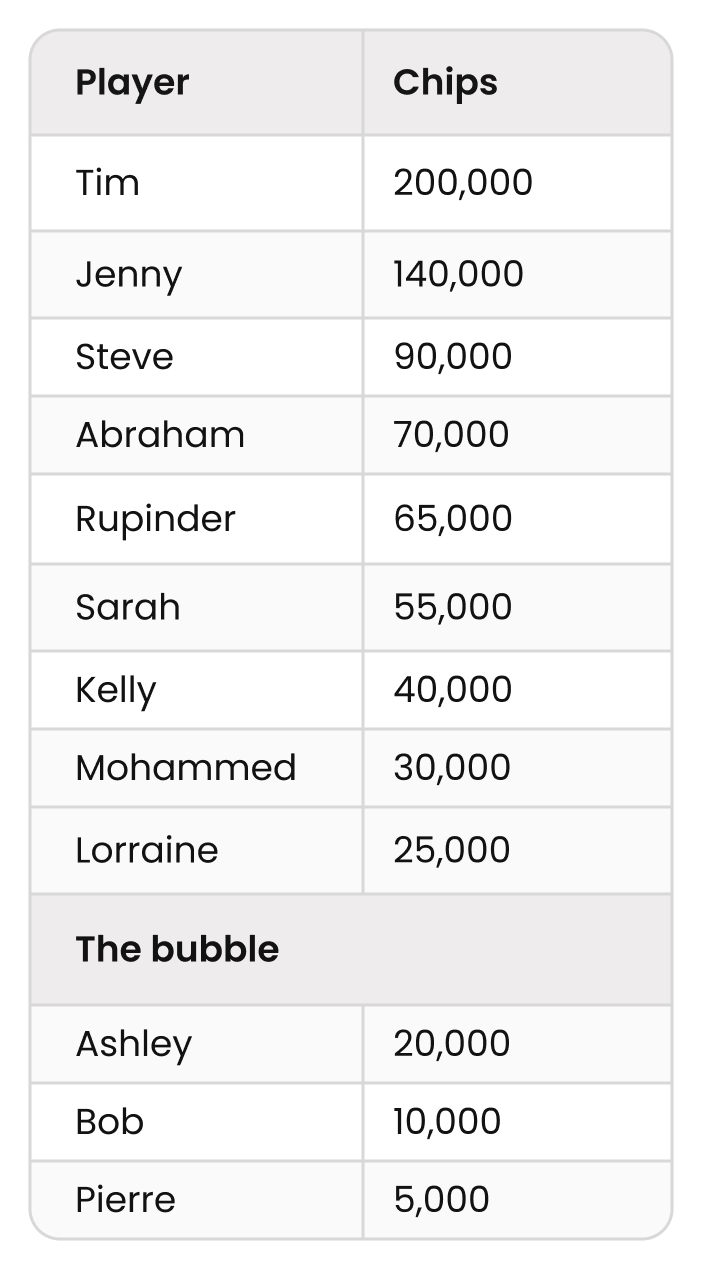

Let’s say there are 10 tickets to be won, and 13 players remain. The online tournament lobby might look like this:

Perspective 1: Inside With #outside < #inside (Rupinder)

In this situation, Rupinder likely has his seat locked up. Four players are between him and the bubble, and three are outside the bubble. He can quite confidently expect that Ashley, Bob, and Pierre will be forced all-in before him, and if some of them survive, Sarah, Kelly, Mohammed, and Lorraine will be forced all-in at some point before him too. Rupinder can usually fold to the money.

Perspective 2: Inside With #outside > #inside (Lorraine)

Lorraine is not so comfortable. The most likely thing is she will survive the bubble, but if Ashley, Bob, or Pierre find a double or two between them, she might get pushed into the danger zone.

Perspective 3: Outside (Ashley)

Ashley should take a profitable spot to accumulate chips—preferably a shove, not a call, because she is not safe.

Stalling

Now we move onto the elephant in the room where satellites are concerned. Of all the formats in poker, satellites are the one where stalling is inevitable. Almost everybody stalls near the bubble in a satellite. It is so prevalent that you are at a disadvantage if you do not do it.

Once you have a seat locked up, there are no extra prizes for having more chips, so there is also no reason to risk the ones you do possess by playing more hands.

Therefore, stalling means you can put off playing hands while other players might be busting out on other tables.

Another incentive to stall, even during hand-for-hand, is if it means that the blind levels will increase on a very short-stacked player’s big blind. It might be the difference between them being forced all-in or surviving another orbit. On the flip side, one of the few times where stalling is not profitable near the bubble is if you are about to pay the big blind. You are then more incentivized to fold fast under the gun to pay it sooner before the blinds go up.

Knowing your relative position in the field is most important in satellites, so much so that scanning the lobby and tournament information screens online should be a habit. If 10 players get a seat and you are 5/11, coasting to a seat is a very probable scenario. But if you are 11/11, you will likely be bubbling if everyone else is blinding out. The only exception to this is if you have just paid the big blind. The lobby may say you are 11/11 but you now have a whole orbit of not paying the blind, and it is likely other players will drop below you before you pay your next blind.

There is an ethical dimension to stalling in satellites. Operators have tried many things to combat stalling. The most notable one is the new milestone satellite format. However, there is also an incentive to stall in those, which is a discussion for another time. I think the most important consideration in this matter is the following:

When stalling is profitable, and everybody does it, then not stalling yourself puts you at a tremendous disadvantage.

It’s up to operators to find a way for it to be no longer profitable or at least not as interesting. In that environment, your win rate would not be affected (as much, if at all) by whether you stalled or not.

Unlike regular tournaments, where the overall play experience is hurt by stalling, everybody in a satellite is happy when other players are stalling on the bubble because it benefits them too.

Conclusion

One topic we didn’t cover is late registration because we have already discussed it at length here. However, a quick note to say that of all the formats:

Late registration is most profitable in satellites because our only goal is to beat the bubble. So, the closer you start to the bubble, the better.

I implore you to tinker with the new GTO Wizard ICM Calculator to see this for yourself.

Because postflop is rare in the endgame stages of satellites, we also didn’t cover the topic in this article. However, it’s fun to play around with the postflop ICM features in GTO Wizard with a satellite payout structure. There’s some really weird stuff that is unseen in any other format.

Whenever you look at the correct strategy for satellites and get confused, remember that everything is built around the premise that:

In a satellite, all prizes are of equal value.

There is no extra prize for having the most chips, so building a strategy around min-cashing is key.

That’s why we can fold AA preflop and also shove any two on the bubble. It’s why we open-shove sometimes with 30bb rather than min-raising. It’s why fold equity is so important and why blockers are perhaps the most valuable in satellites.

Fundamentally, we should play much tighter in satellites and avoid calling off for our tournament life. As you learn the format, it’s not a terrible idea to play two or three pips tighter than you normally would (e.g., call QQ+ in a satellite, when normally you would call 99+, etc.). For the most part, if you think you are being too tight, you probably are not.

Author

Barry Carter

Barry Carter has been a poker writer for 16 years. He is the co-author of six poker books, including The Mental Game of Poker, Endgame Poker Strategy: The ICM Book, and GTO Poker Simplified.

Wizards, you don’t want to miss out on ‘Daily Dose of GTO,’ it’s the most valuable freeroll of the year!

We Are Hiring

We are looking for remarkable individuals to join us in our quest to build the next-generation poker training ecosystem. If you are passionate, dedicated, and driven to excel, we want to hear from you. Join us in redefining how poker is being studied.