The Initial Bettor’s Advantage

The mathematics of poker holds a little-known secret: the first bettor enjoys better bluffing odds than someone who raises by the same amount. In this article, we’ll explore the calculations behind this phenomenon and discuss how this plays into theoretically optimal strategies.

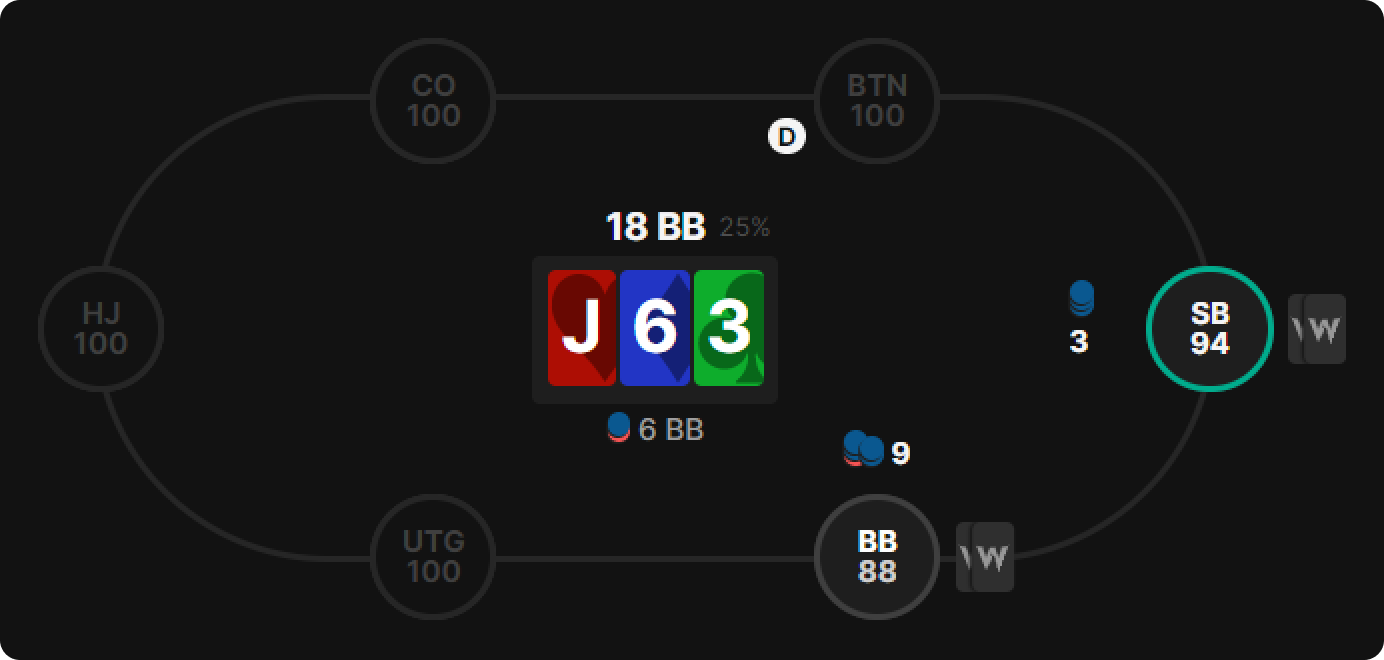

Let’s start with an example to illustrate this principle. Blind vs. Blind, Single-raised pot:

- The pot is 6 bb

- SB bets 3 bb (50% pot-sized bet)

- BB raises to 9 bb (50% pot-sized raise)

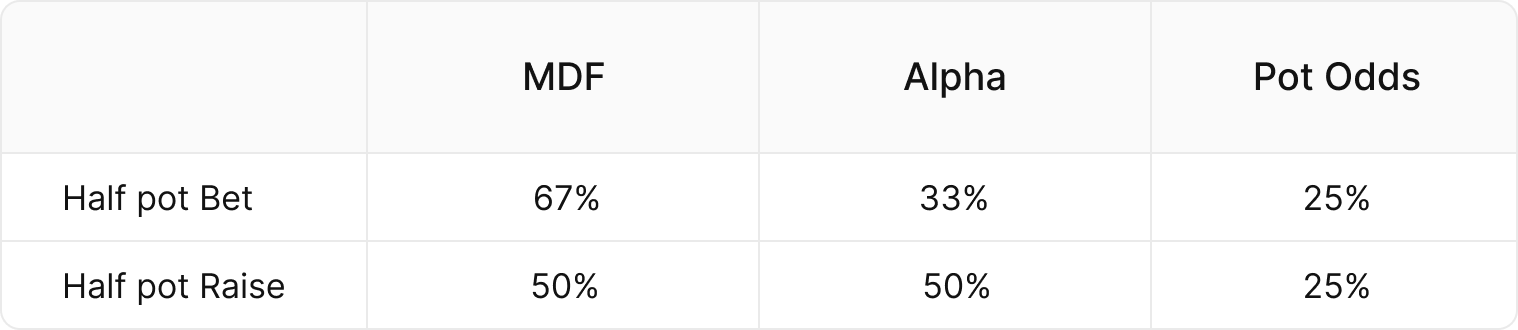

Let’s calculate the bluffing odds for both players. This calculation is also known as Alpha, or 1 – MDF. You can read more about that here, but to recap:

Breakeven Bluff = Risk / (Risk + Reward)

Where:

- Risk is the amount risked with a pure bluff. Or how much you would lose if your bluff fails.

- Reward is the amount gained if your opponent folds, compared to if you had given up.

SB needs 3 / (3 + 6) = 33% fold equity to profitably bluff the initial bet.

BB needs 9 / (3 + 6 + 9) = 50% fold equity to profitably bluff-raise the bet.

Both players risked the same fraction of the pot. Therefore, both the bet and the raise lay the same pot odds. Despite that, the initial bet required less fold equity for a bluff to be profitable! We can also consider the inverse calculation, MDF. The Minimum Defense Frequency describes how often players must defend to prevent the opponent from profitably bluffing. SB facing the raise is only required to defend, at most, half their range. BB facing the initial bet is required to defend two-thirds of their range.

However, the pot odds requirements have not changed. In both cases, either player should continue with hands that can claim more than 25% pot share. In summary, facing a raise you don’t need to defend as wide compared to facing an initial bet of the same size, while at the same time, the equity required to profitably call does not change.

Visualizing This Effect

The following table shows how much extra fold equity you need when raising, compared to if your raise was the initial bet. For example, a 50% bet needs 33.3% fold equity. But a 50% raise over a 30% bet requires 45.83% fold equity, resulting in a required surplus 16% fold equity! Put another way, the half-pot raise over the 30% bet requires your opponent to fold 16% more often before your bluffs break even.

We can see the effect is strongest at the minimum raise size, where you’d normally get the best price on a bluff. This often ties into block-betting theory – but more on that later.

The reason behind this effect is actually fairly intuitive. The initial pot is a prize that incentivizes bluffing and calling. As a series of raises occurs, the size of the initial pot shrinks relative to the “reward” part of our calculation. To make it more intuitive, imagine you’re facing a 100bb 5bet shove preflop. The initial 1.5bb unopened pot now has little bearing on the risk/reward ratio of this shove. The same concept applies here. As a series of bets and raises fly in, the initial pot which had originally incentivized betting becomes less relevant.

It should be noted that just because you get a slight mathematical advantage when bluffing, that doesn’t give you a free license to start leading every spot! There are still many spots where you should check range.

Practical Example

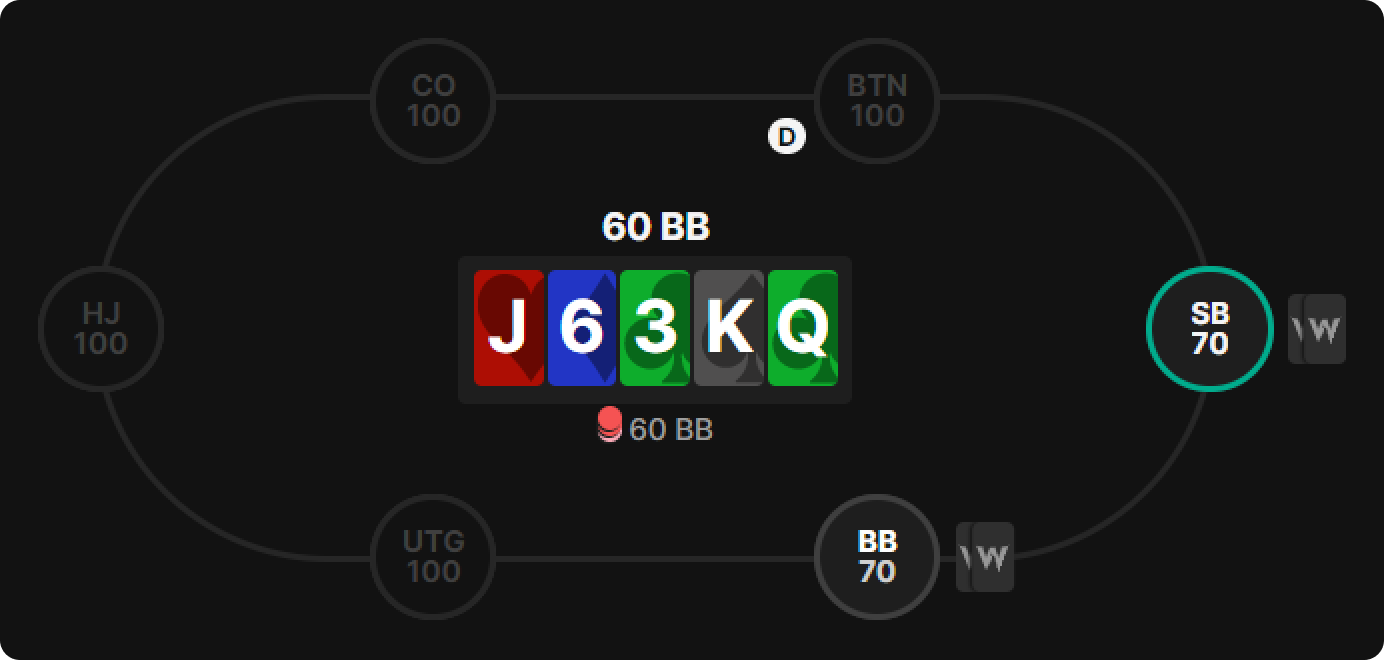

Let’s return to our previous example. SB opens 3, BB calls. Flop’s J♥ 6♦ 3♣. SB c-bets half-pot, BB raises half-pot, SB calls. Turn is the K♠. BB barrels 75%, SB calls. River is the Q♣.

The Queen of clubs is a decent card for SB here. It turns many of their weak one-pair hands into two pair. For that reason, SB develops a donking strategyDonk bet

Any bet made by a player before the previous street aggressor has had an opportunity to act. A donk bet can only be made by a person out of position relative to the last aggressor on the previous street. – leading into the aggressor.

The SB called a flop raise and then a big turn bet, so their range is mostly condensed towards made hands with few draws at this point. The BB, however, arrives at this unfortunate river with too many bluffs. This wasn’t a mistake in their strategy, this is just the nature of Hold’em. Some runouts favor you; others do not.

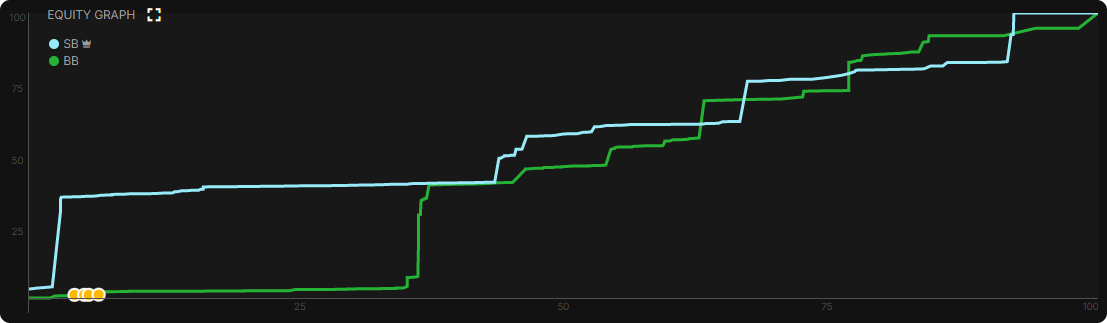

We can see by observing the equity distribution that no player really has the nut advantage, but SB has an equity advantage by virtue of not having trash in their range.

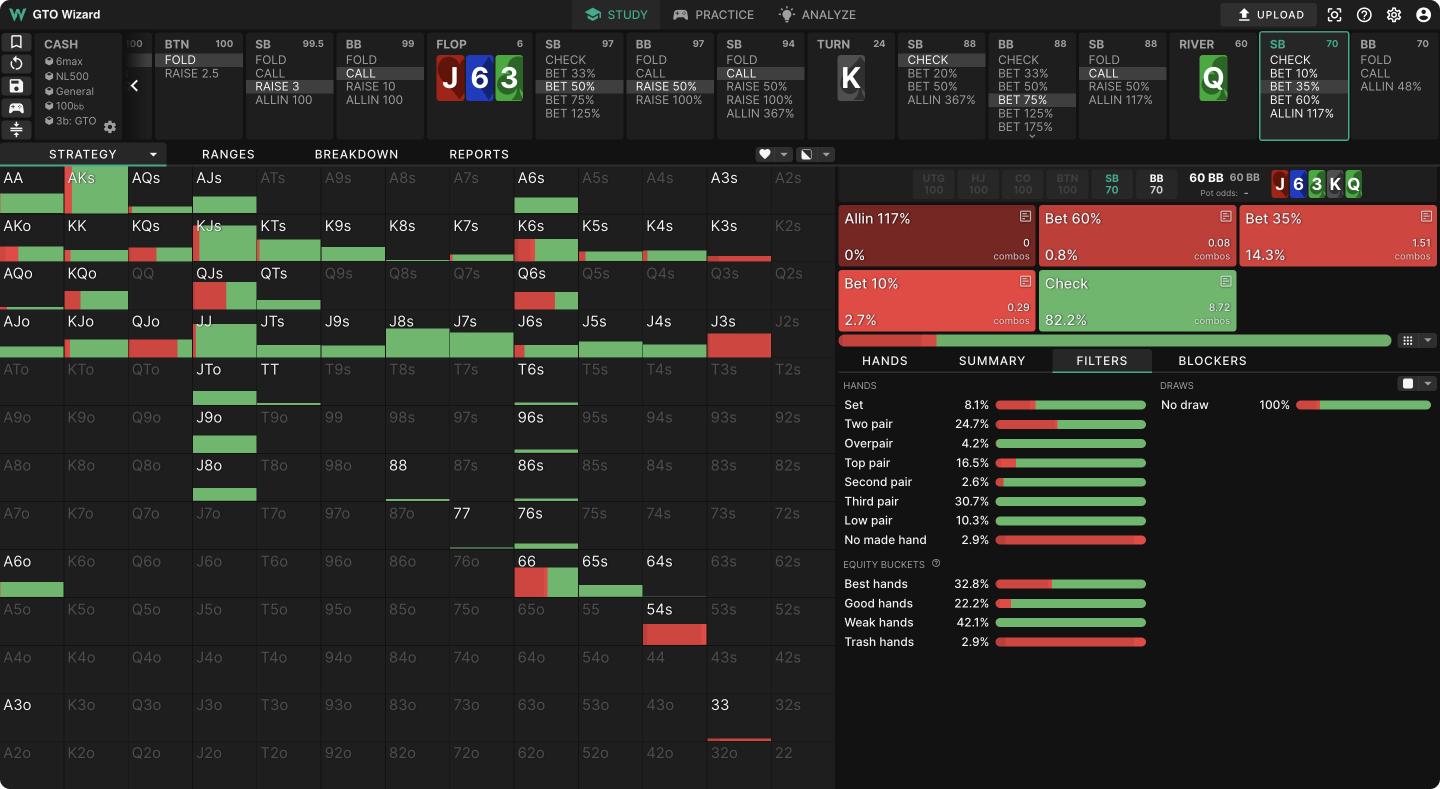

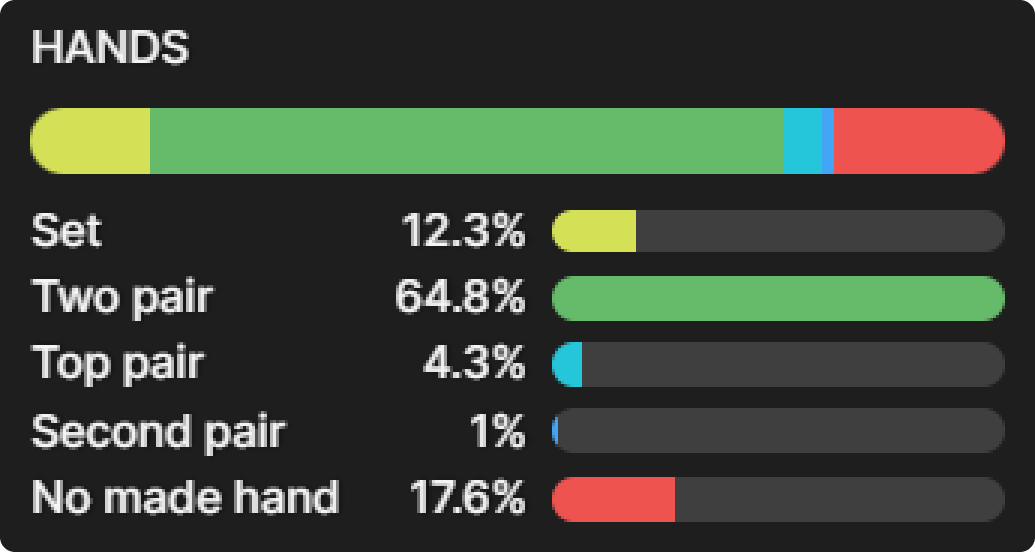

The SB therefore donk leads 35% pot representing a range of two pair+ for value, along with some marginal top pair. The following chart displays the donk bet construction:

There are several reasons for this bet. One is to push their middling equity advantage. Another is that, if they had range-checked, BB could check back more to exploit them. But one of the deeper reasons, buried within the mathematics of the game, is that the SB’s lead grants them favorable bluffing odds compared to check-raising.

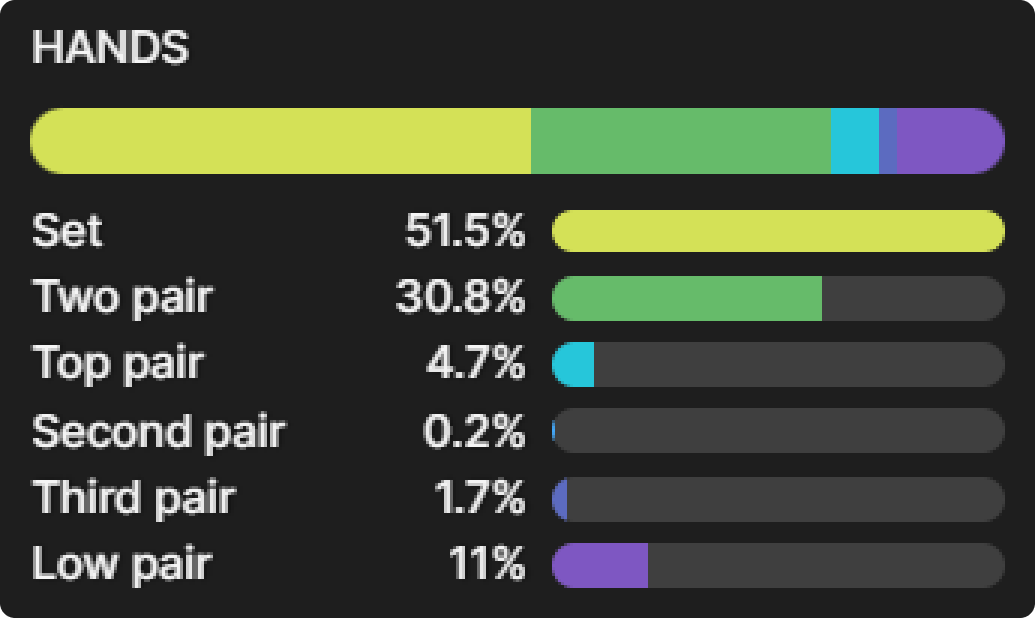

Facing this donk bet, the BB has a 48% pot shove behind, which they utilize about ⅓ of the time. However, despite their raise being bigger than the donk, they are required to bluff less often.

When the BB does shove the last half-pot, SB only needs to defend 50% of their range, as opposed to the 67% that would be required if we had instead checked and faced a half-pot bet.

Summary

When comparing the mathematical consequences of a 50% bet against a 50% raise we see that, unlike pot odds, MDF and Alpha do not scale with pot%. This leads to four key takeaways:

- The initial bettor gets a better price on a bluff than a raise of the same size.

- You should defend less often facing a raise than an initial bet of the same size.

- Facing a raise, the defender has a slight advantage, as they are not obligated to defend as wide (compared to a bet of the same size), but the required pot odds to call haven’t changed.

- This often ties into block-betting theory, especially on the river.

Author

Tombos21

Tom is a long time poker theory enthusiast, GTO Wizard coach and YouTuber, and author of the Daily Dose of GTO.