Understanding Which Mistakes Cost You the Most Money

I am fortunate enough to have worked for many years with the mental game coach Jared Tendler, whom I co-wrote The Mental Game of Poker with. Of all the advice he had given me, the one I remember the most related to periods when I did not know what to study. This was way before the time of solvers, so there weren’t the tools we have available today to drill down on leaks. His advice was:

If you don’t know what to study, study your C-game

What he meant by this was to identify your biggest mistakes and work diligently to reduce them. Your biggest mistakes likely cost you the most money, they probably hurt the most emotionally when you make them, and they are perhaps the easiest to identify. You get more bang for your buck with this approach.

In the solver era, my other writing partner, Dara O’Kearney, essentially showed me the same approach to study from an EV perspective. Some types of mistakes cost more than others, and the solvers show that. You can see how much an error costs you today, so there is no excuse not to drill down on the most harmful ones.

Thankfully GTO Wizard shows you just how costly any type of error is because in the hand grid it shows you the EV of every action, measured in BBs. Today we’ll explore this feature further and show how to use it to guide our study.

Preflop mistakes

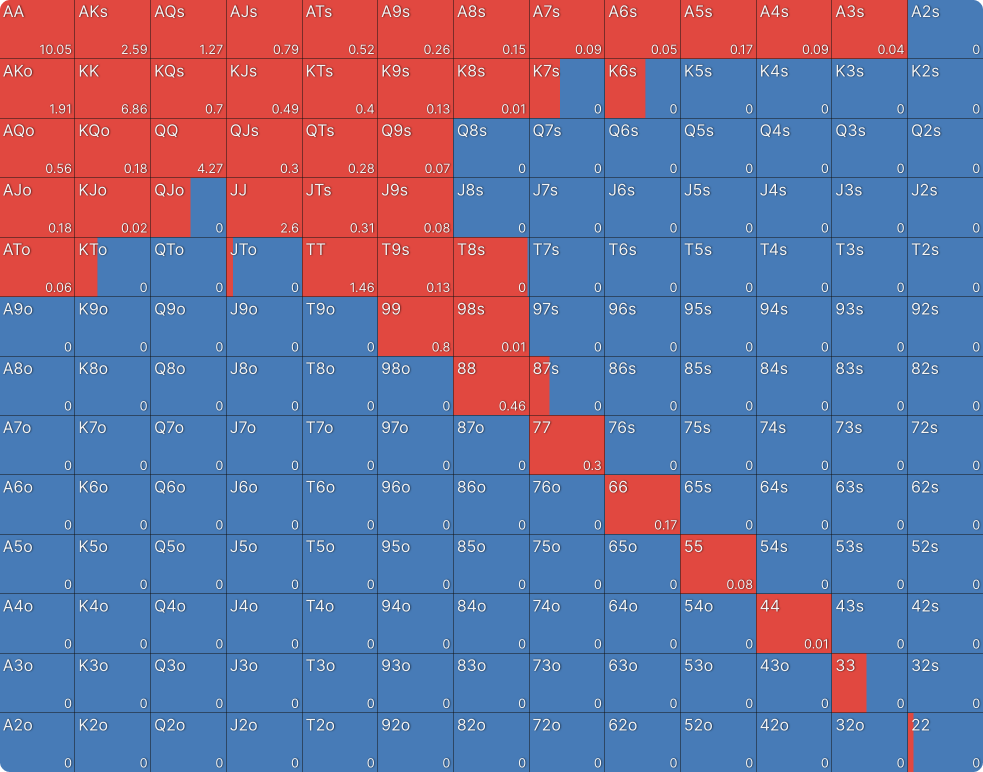

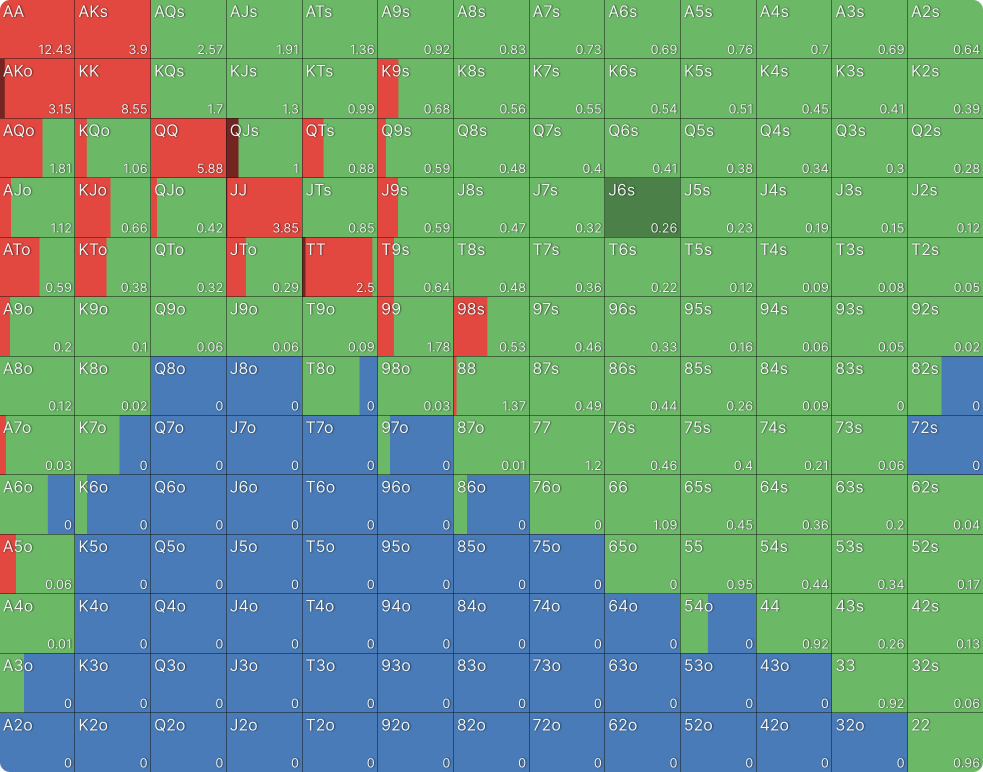

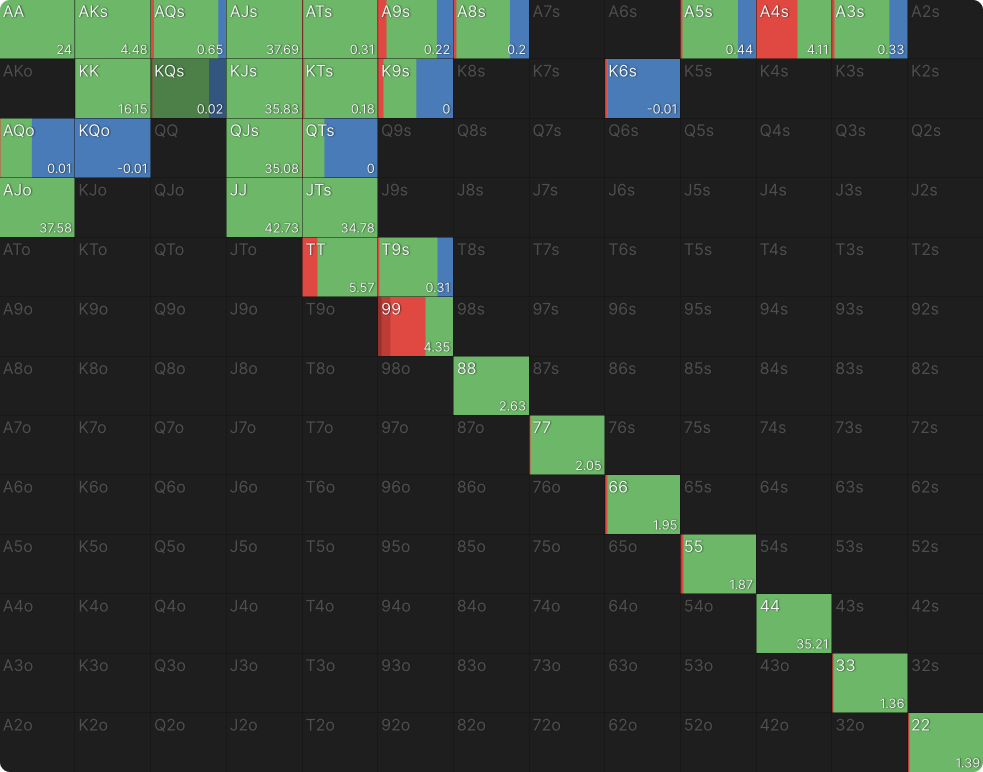

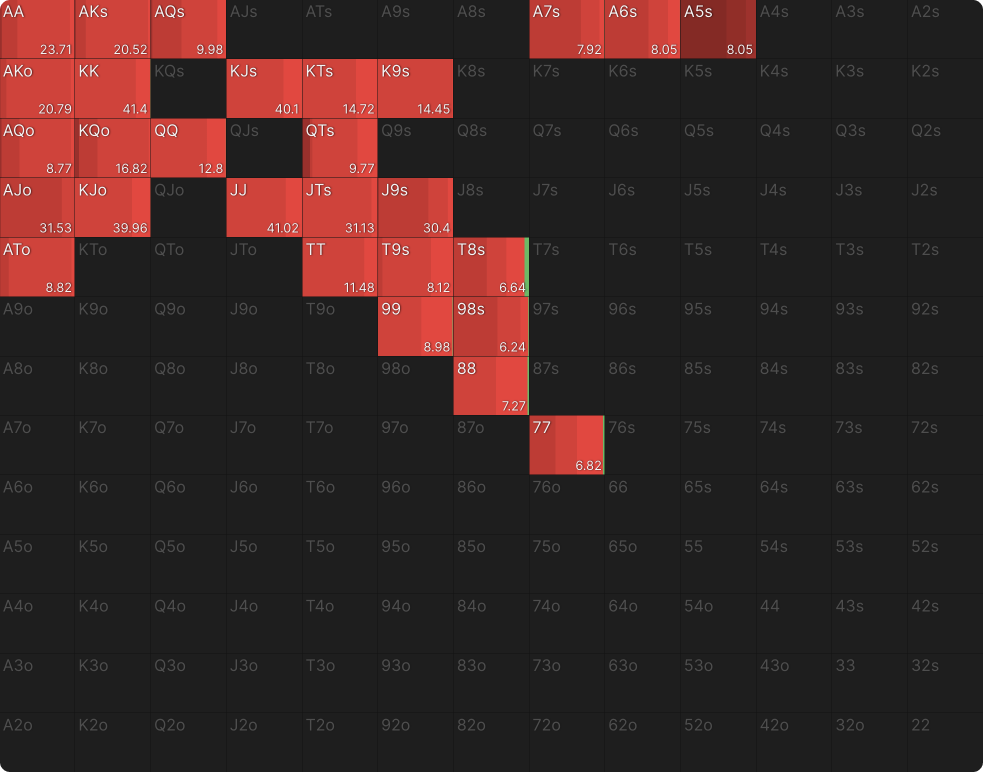

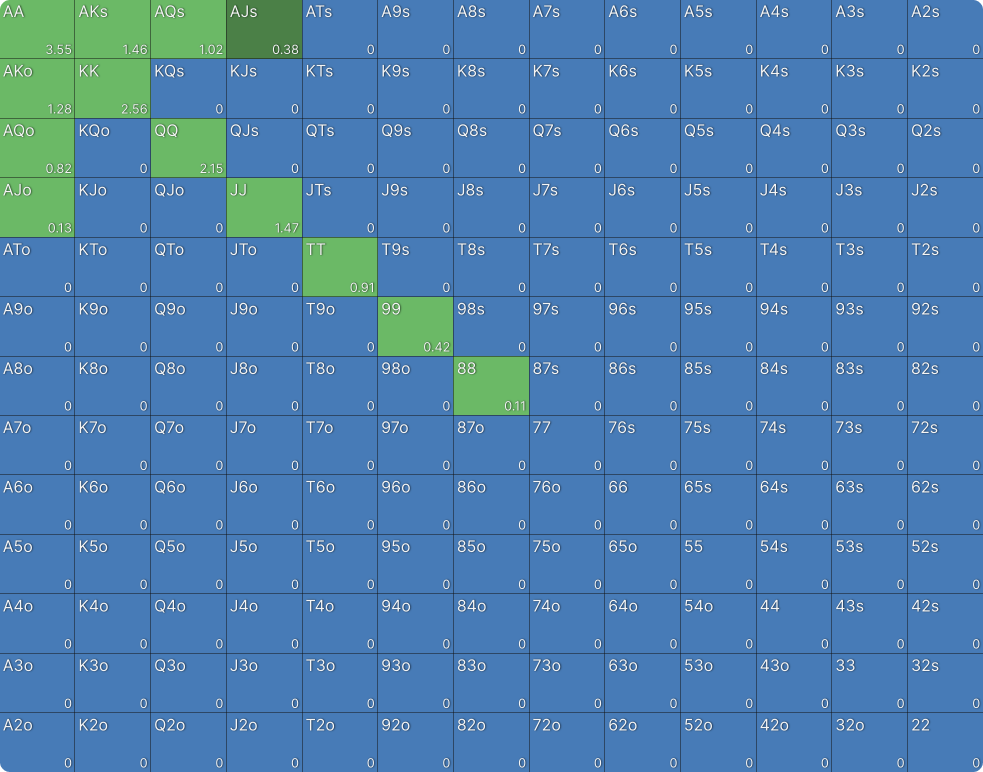

Let’s begin with a simple example. This is a chipEV 40bb effective MTT opening range from UTG.

You can see the overall EV of every hand, as an open, in this grid already. As you can see, AA is very profitable, making us 10.05BBs on average, whereas 44 is almost break even, making just 0.01BBs. Hands we don’t play, like Q8s, obviously have an expected value of 0.

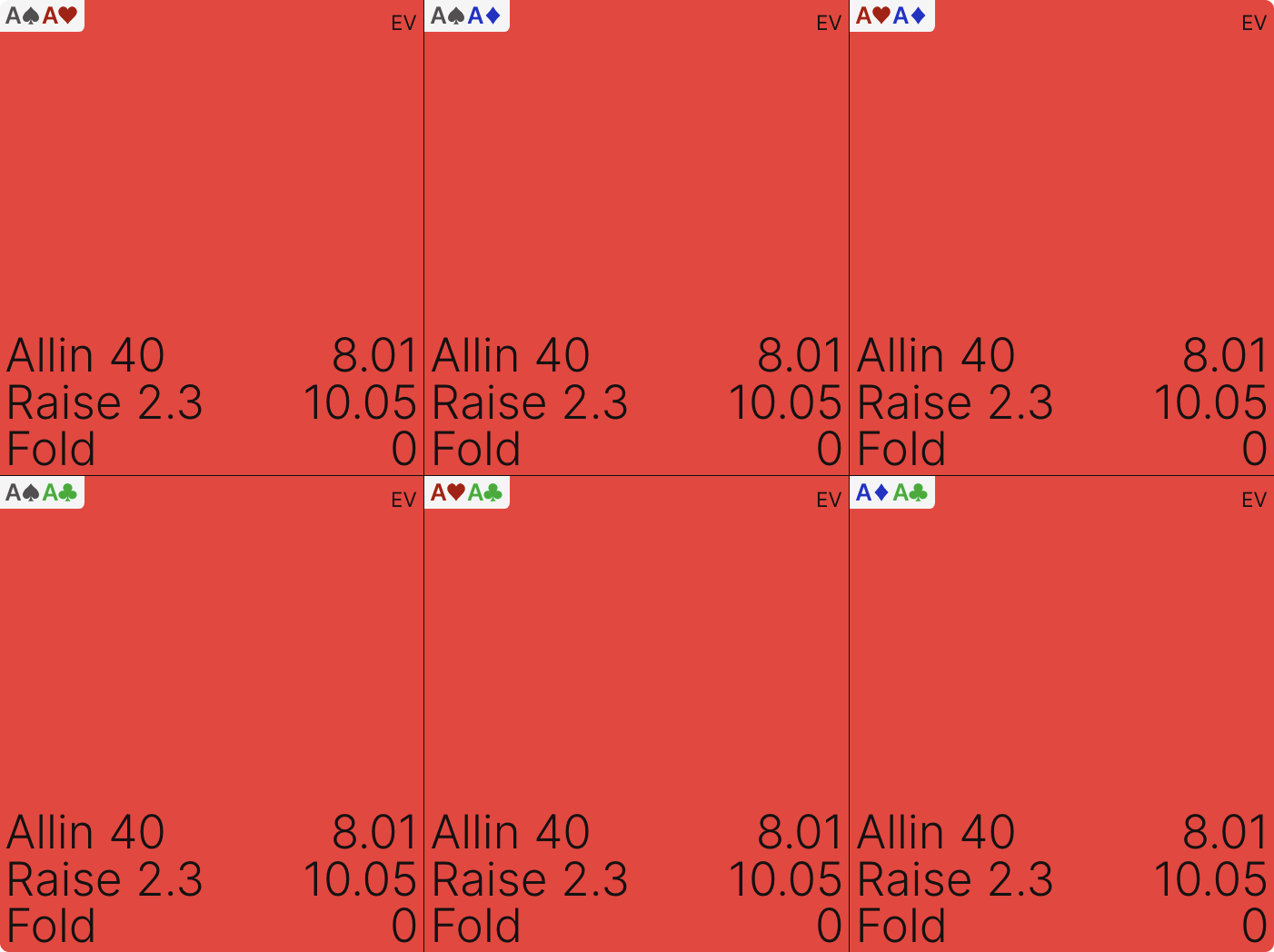

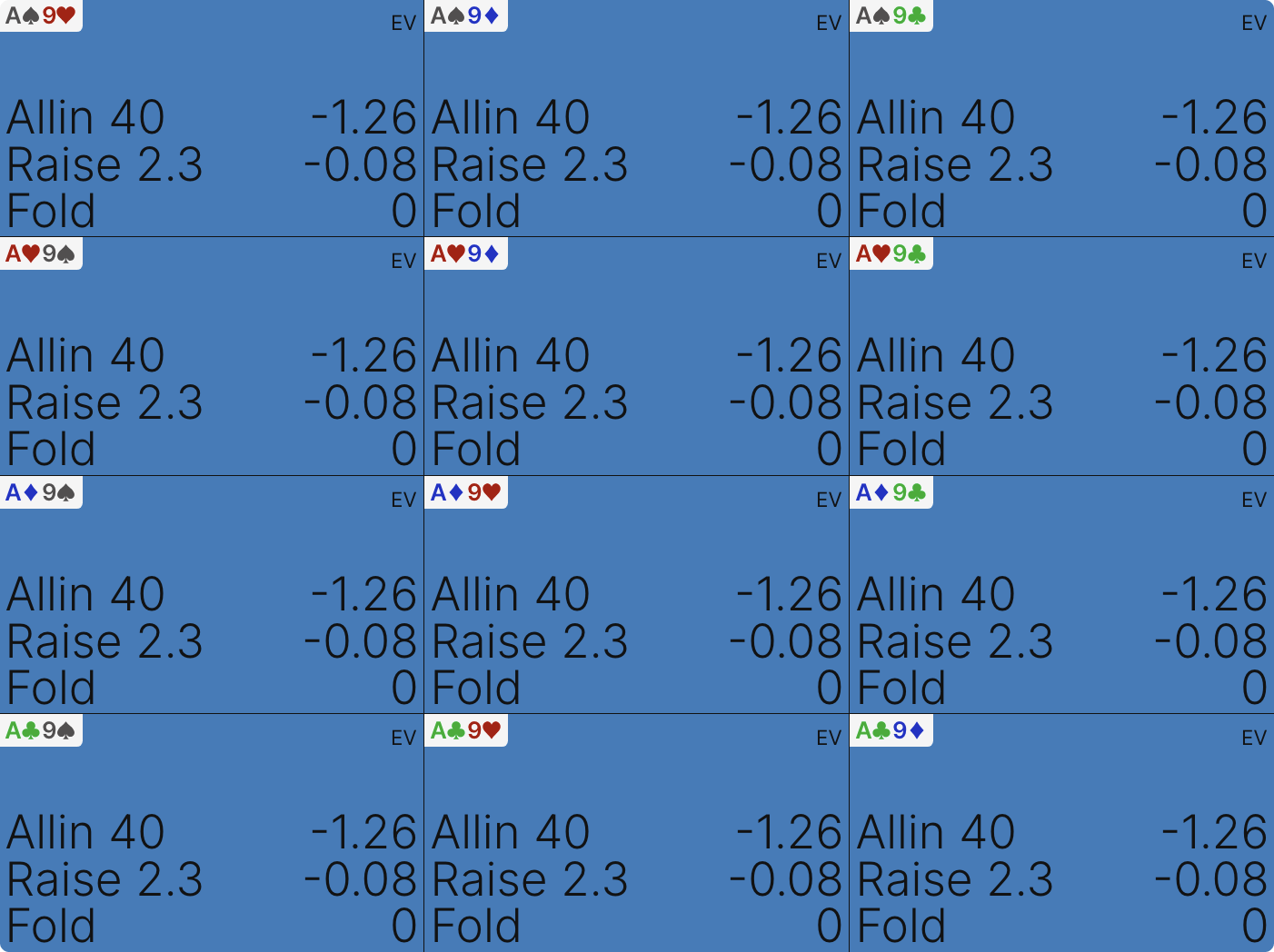

When you hover over a hand, it will give you the specific EV of every action, you could take.

As you can see, shoving with AA is profitable and makes us 8.01BBs on average, but opening with it is much more profitable because we want to induce action with such a strong hand, not scare it away.

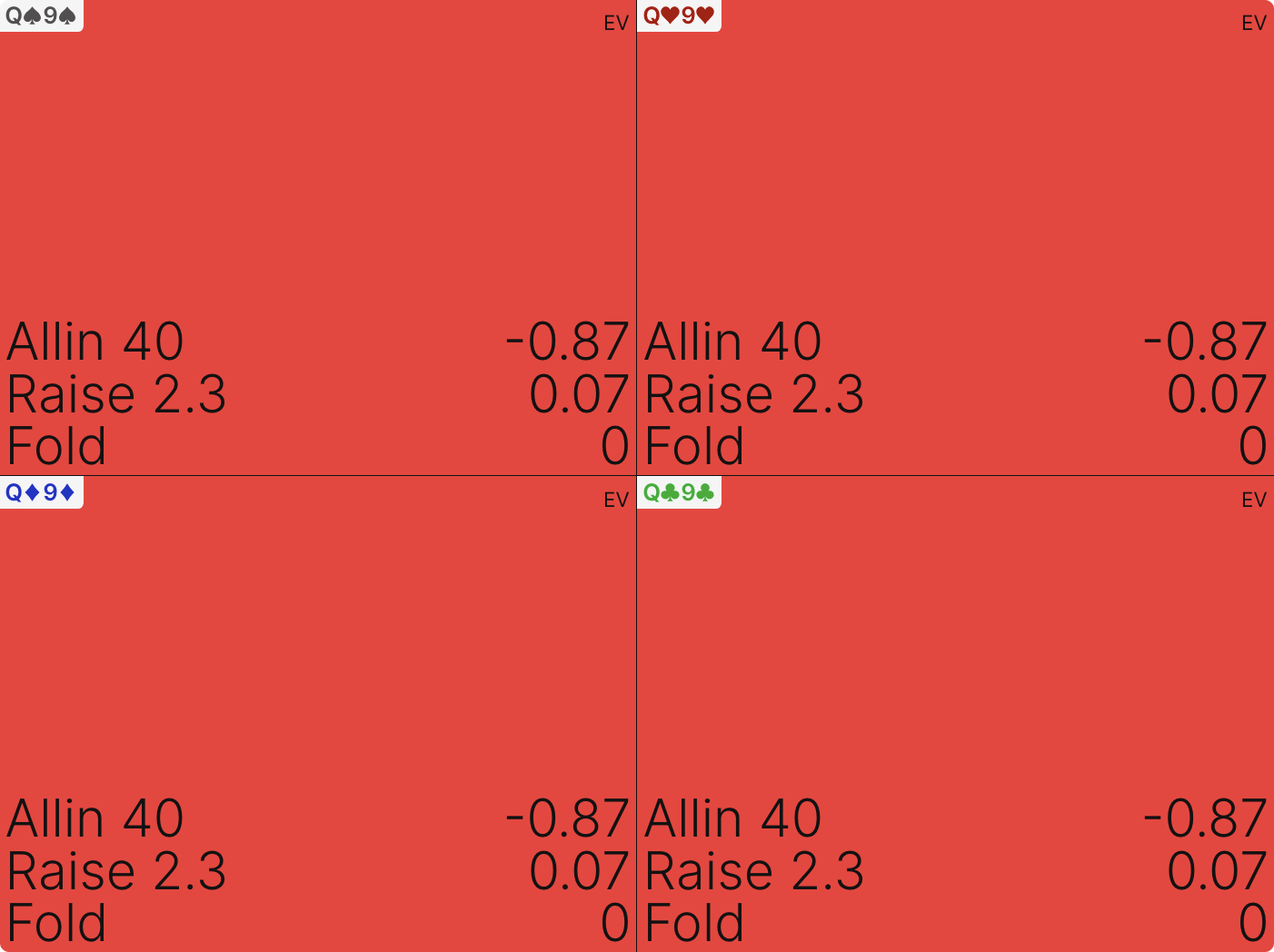

Some hands, like Q9s, make us money with one action but not another:

Here opening makes us 0.07BBs on average but shoving costs us 0.87. The difference between the two actions is 0.94BBs. This is because a hand like Q9s plays well postflop, but if we get reraised we are probably going to fold. When we shove with Q9s we will only get called by a hand that is comfortably ahead of it, making it a -EV option.

This is perhaps quite obvious. The differences between the hands on either side of the margins are more interesting to explore. It shows us just how costly getting the bottom of your range wrong is.

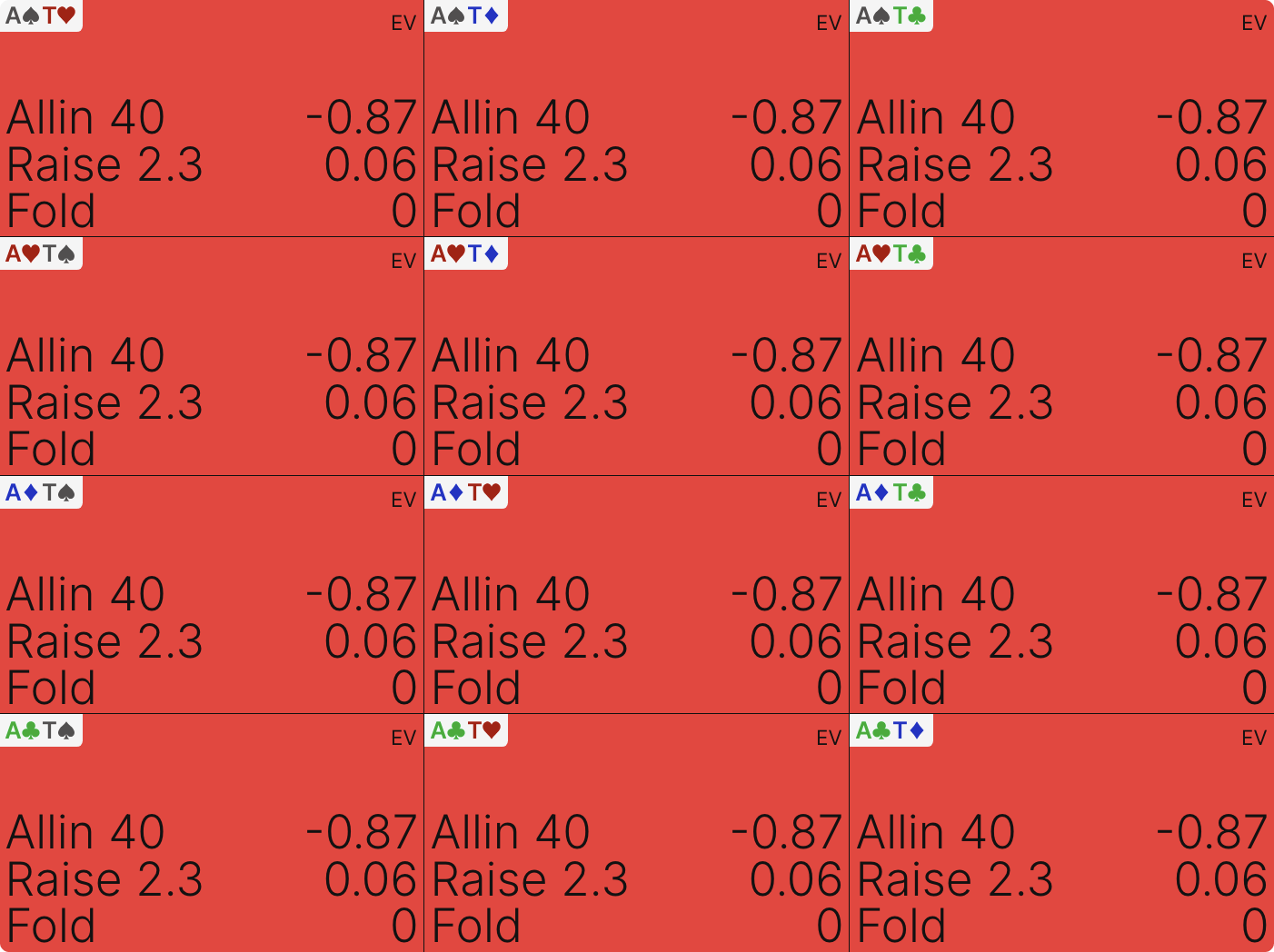

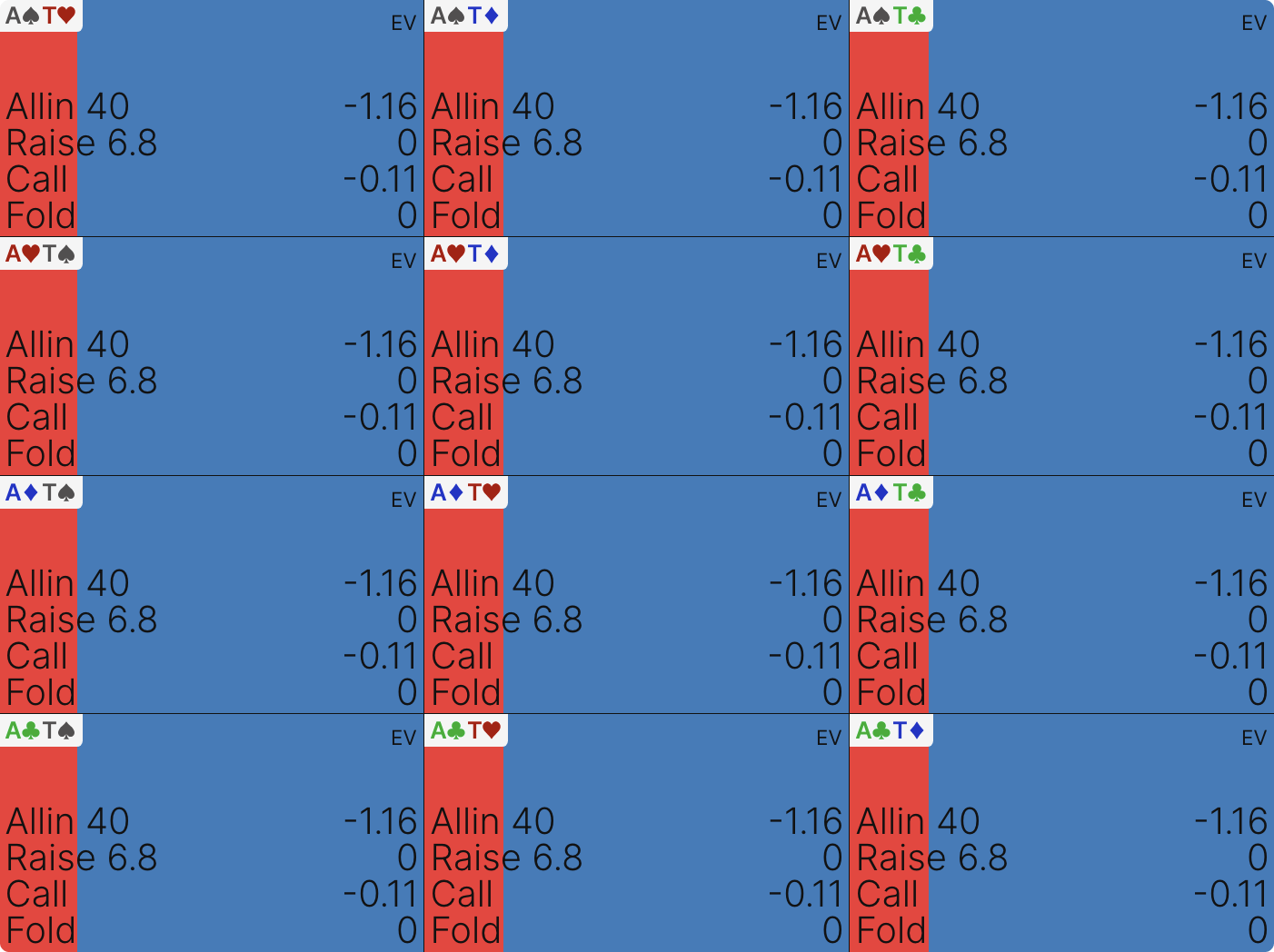

In this example, the worst offsuit Ace we open is ATo:

ATo is also an unprofitable shove, but as an open we make 0.06BBs on average. Let’s compare that with the hand that is just one ‘pip’ outside of the range, A9o:

If you played A9o in this spot, then looked it up later and saw that it was an error, you might rationalize that you were ‘close’ and it wasn’t a big deal.

It is a big deal.

Opening with A9o costs us 0.08BBs. The difference between this and ATo is 0.14bbs. Getting the bottom of the range wrong by a single ‘pip’ is therefore quite costly. If you are an MTT player a 0.14bb error might not sound like much, but as cash game players know these errors compound over a large sample. This is a 14bb/100 error long-term if you always made this mistake from this position.

Small errors compound over a large sample and can cost you a lot more than you realize.

Assuming UTG opens the correct range and action folds around to the Big Blind, this is the response:

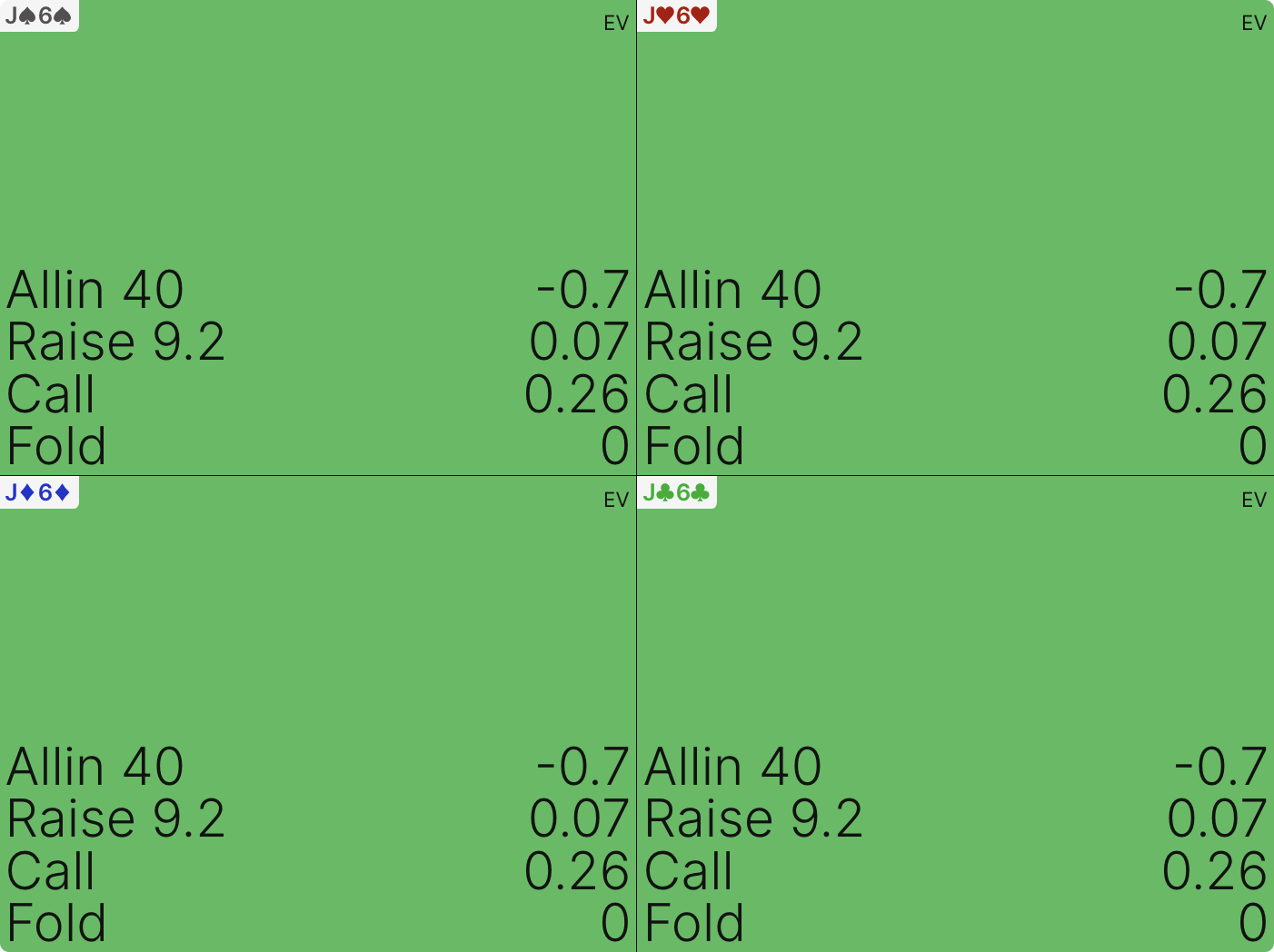

As you can see, the BB continues with more than half their range because they are getting a good price to call, and they get to close the action. If you are unfamiliar with the concept of Minimum Defence Frequency, this is a good jumping-off point. Take a seemingly weak hand like J6s:

The difference between calling and folding is quite significant. There is a 0.26 difference, which is greater than the difference we saw in the previous example where UTG opened with the wrong hand. Folding may seem the ‘safe’ option but you are burning money doing it, this is a 26 bb/100 error.

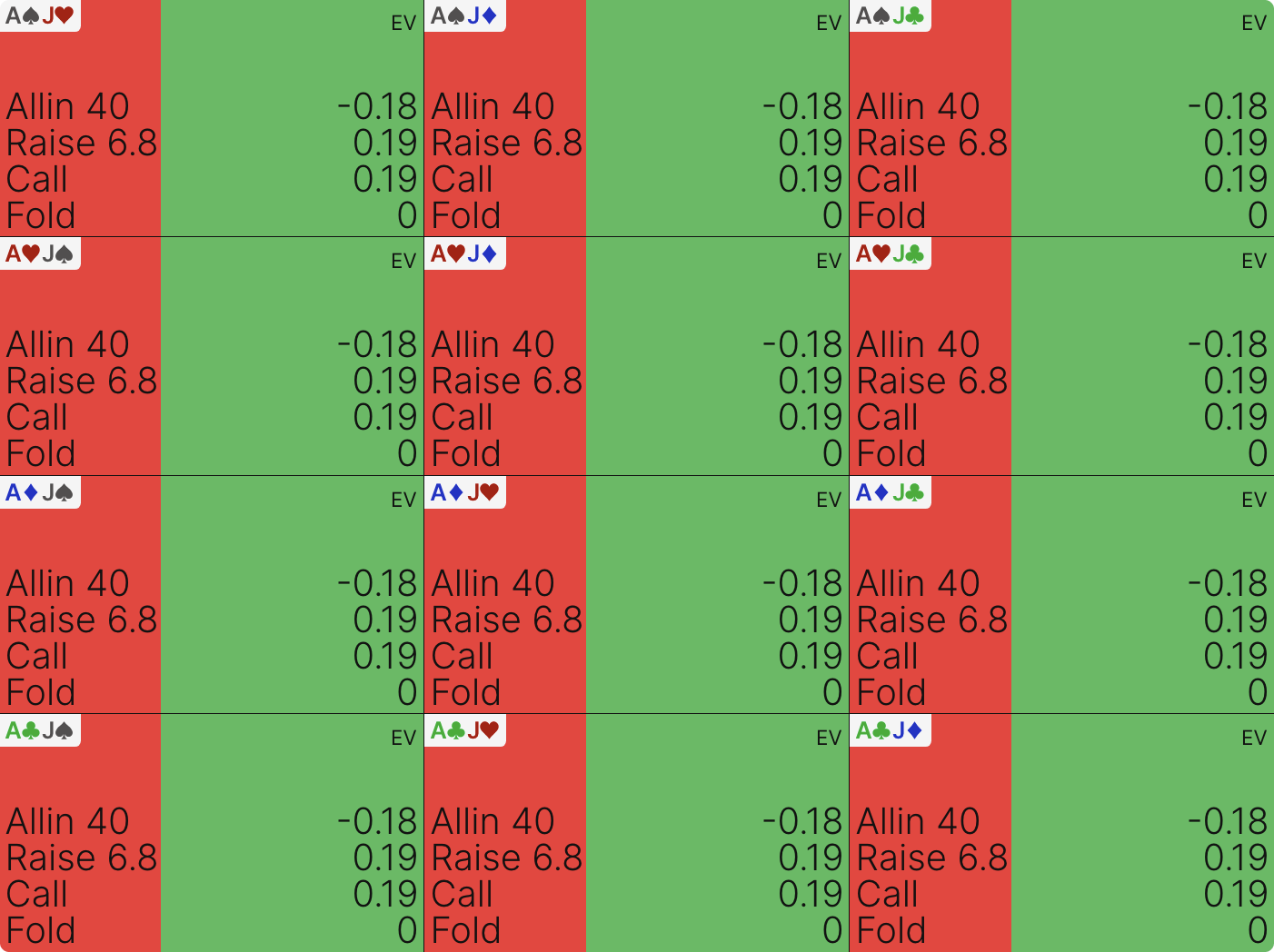

Let’s go back a step and instead use an example where the responding player does not have blinds invested. Let’s go back to the UTG open, but this time it is the HJ mulling over their response:

The weakest offsuit Ace the HJ can call with is AJo, which makes them 0.07bb.

Interestingly, the first hand outside of the range is still an occasional continue. ATo is never called, but sometimes raises.

This is because ATo does not play well against an UTG open, but does work as a bluff because it blocks the strong Ax hands that make up a big portion of the range. It is a breakeven bluff, but loses the HJ 0.11bb as a call. The difference between calling with AJo and ATo is 0.18bb. As you can see the differences between a correct call and a losing call, at the bottom of our range, is getting bigger. A bad call here, just one pip out, costs us 18 bb/100 over a big sample. This also highlights that an error in the way that you continue can be significant.

Some hands are profitable bets but not calls, some hands are profitable opens but not shoves, and vice versa. The EV outputs in GTO Wizard not only show you the profitability of actions, but also illuminate the rationale underlying some of these actions.

The EV outputs in GTO Wizard not only show you the profitability of actions, but also illuminate the rationale underlying some of these actions.

Back to calling and let’s make the gap between the hands a little wider, for example, if we call with A9o which is the first hand we should not continue with at all, this is what you get:

Calling with AJo makes us 0.07BBs, calling with A9o loses us 0.42BBs, the difference between the two is now 0.49BBs. This is significant, over a large sample this is a 49 bb/100 mistake if we keep making it. Getting a call wrong by one pip is bad, getting it wrong by more is hemorrhaging money.

Postflop mistakes

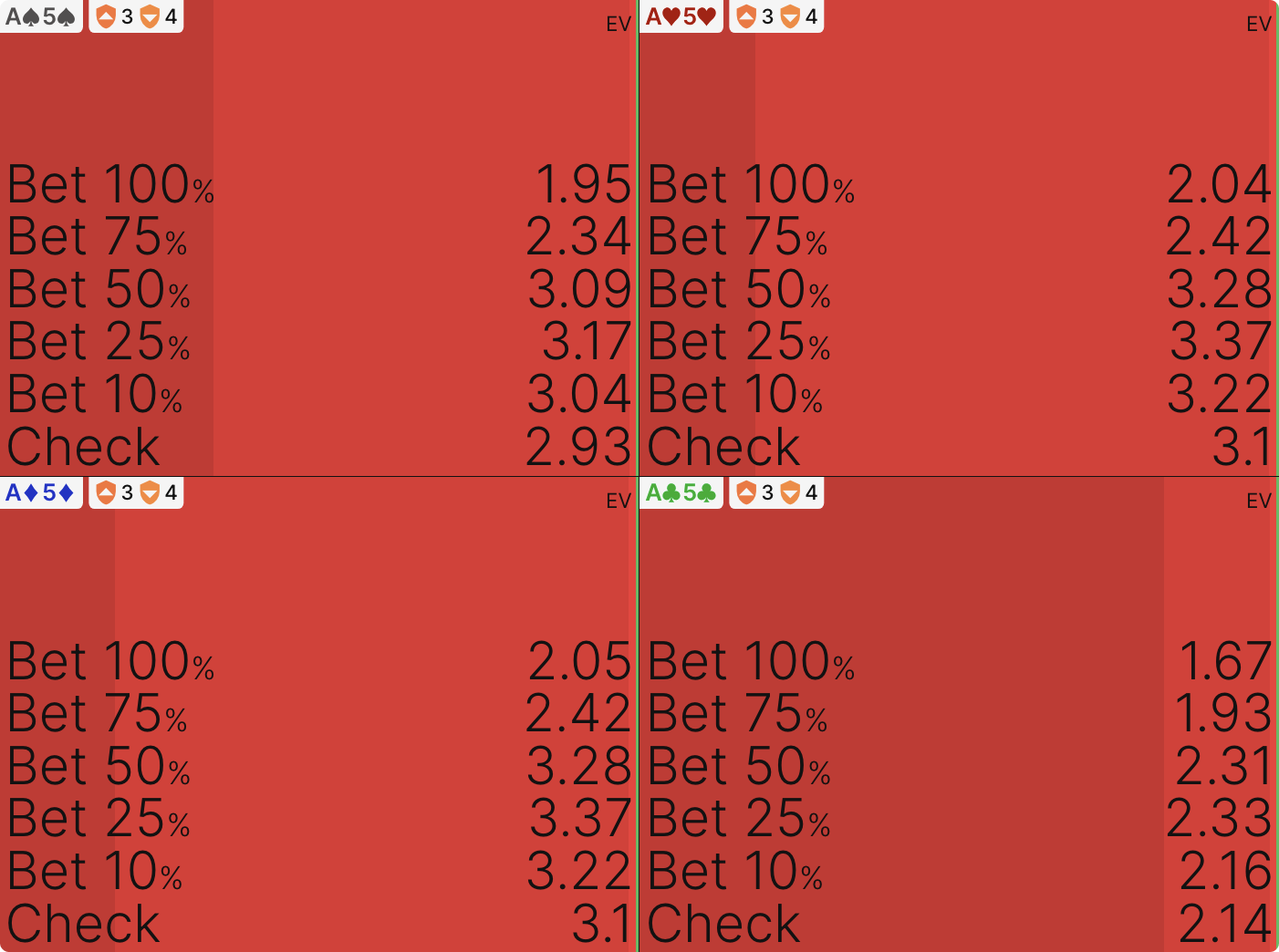

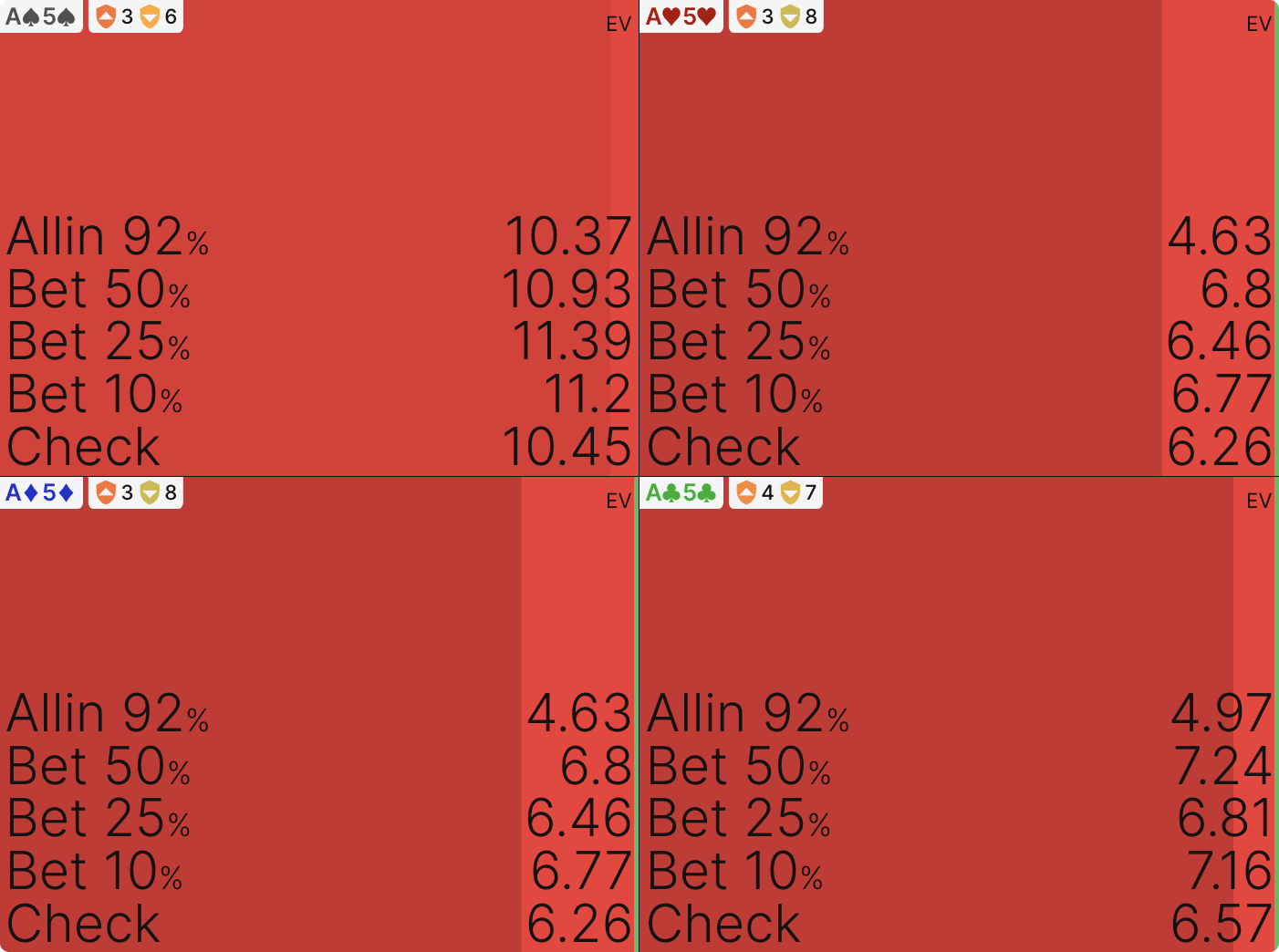

In this example, UTG has opened with 40bbs effective, the SB has 3-bet and UTG has called. The flop is J♥J♦4♠. On this flop the SB bets almost their entire range, favoring the 25% bet size.

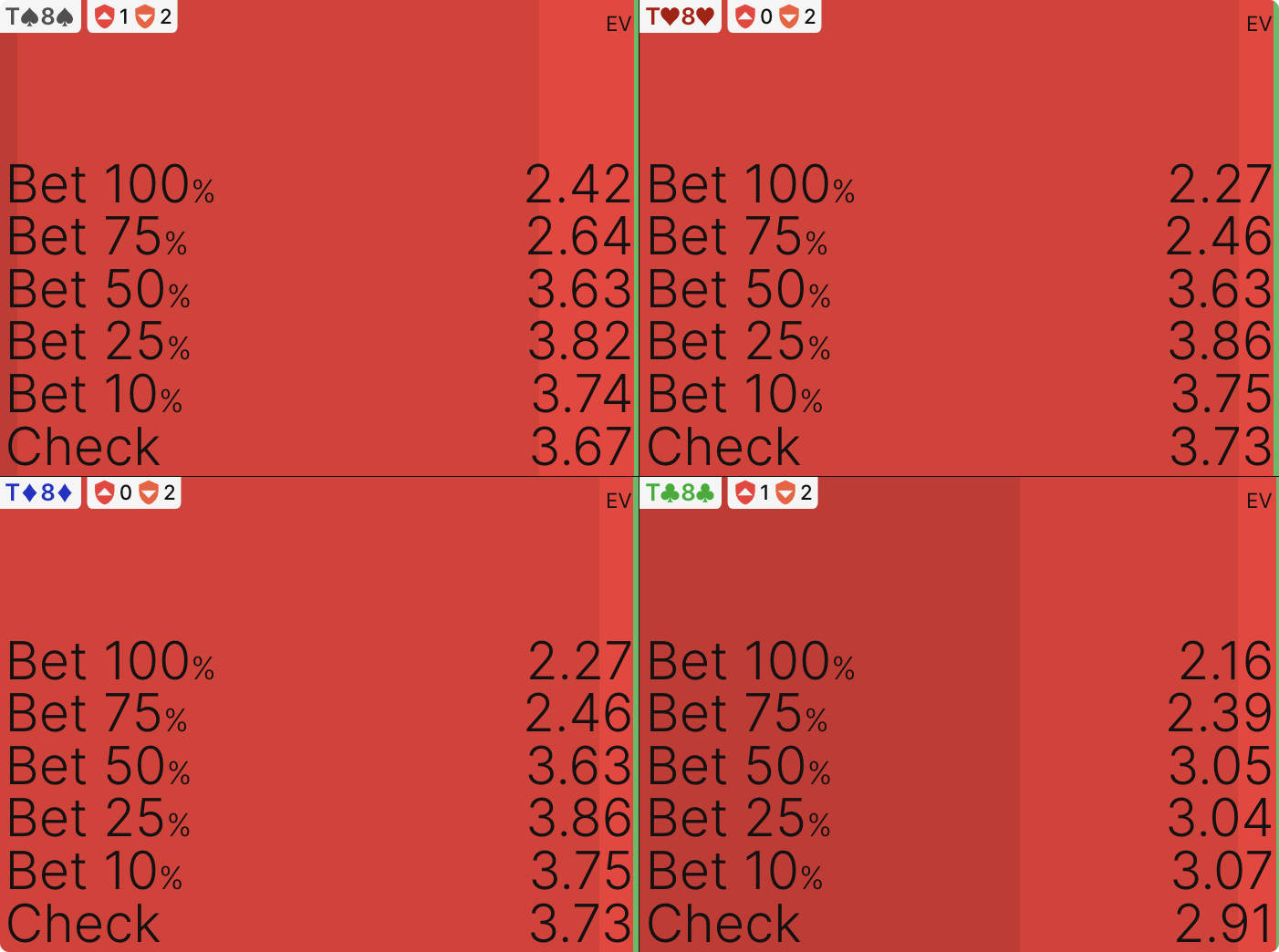

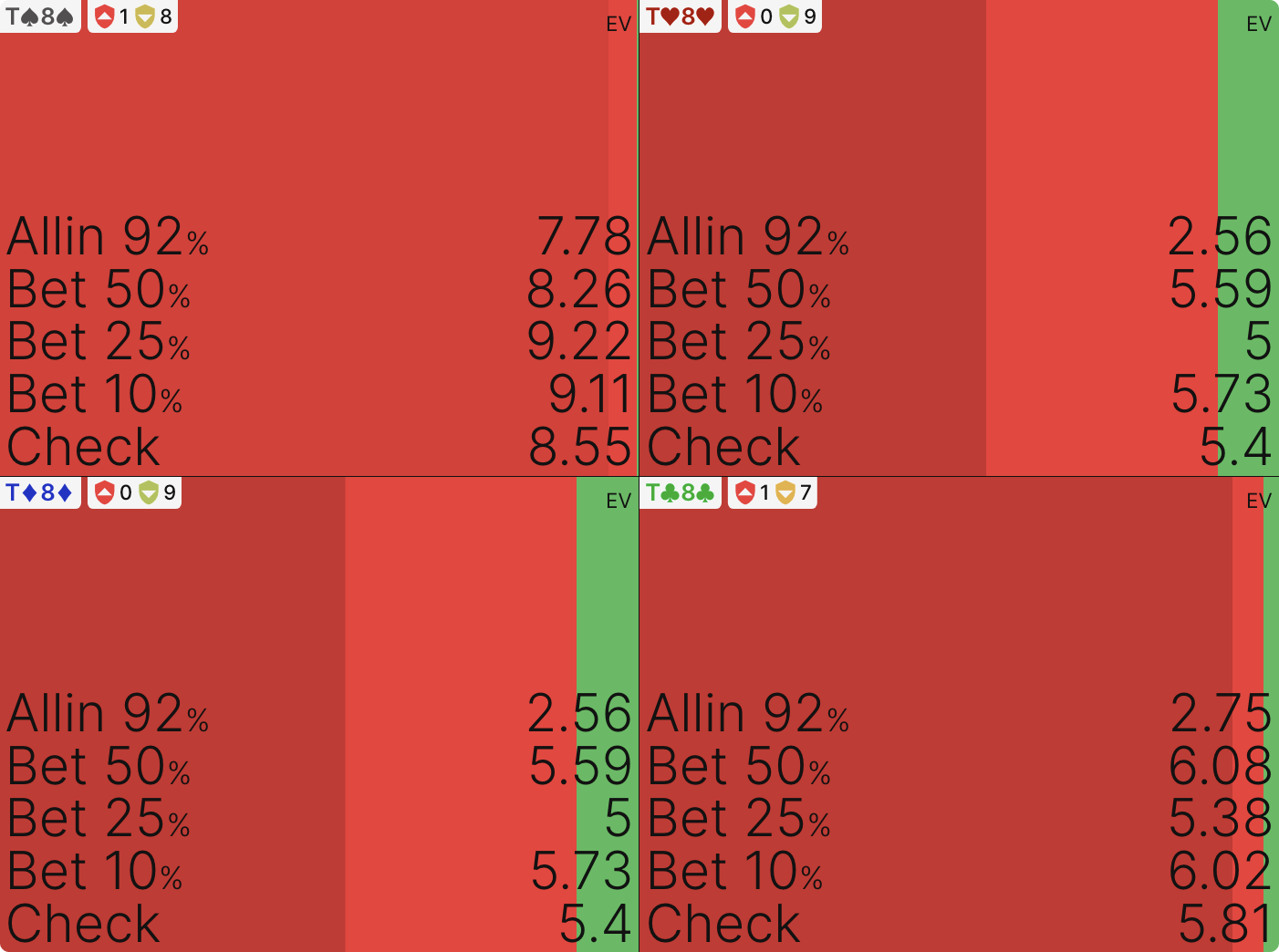

This is a classic range bet, whereby the most profitable strategy is to bet the entire range for a small bet size, because the SB has significant range advantage. You can see this by looking at the EV of every action for a random sample of hands.

Whether the hand is nutted, medium strength or a complete miss, the most profitable action is the 25% bet. It might be tempting to go bigger on a board like this with the very strong KJs or the complete miss that is T8s, to extract more value with the trips and make a fold more likely with the miss, but this shows that would be an error. The difference between betting 50% pot with KJs and betting 25% can be as much as 0.31BBs, a 31 bb/100 error. It might seem like a small mistake and but is actually a huge error.

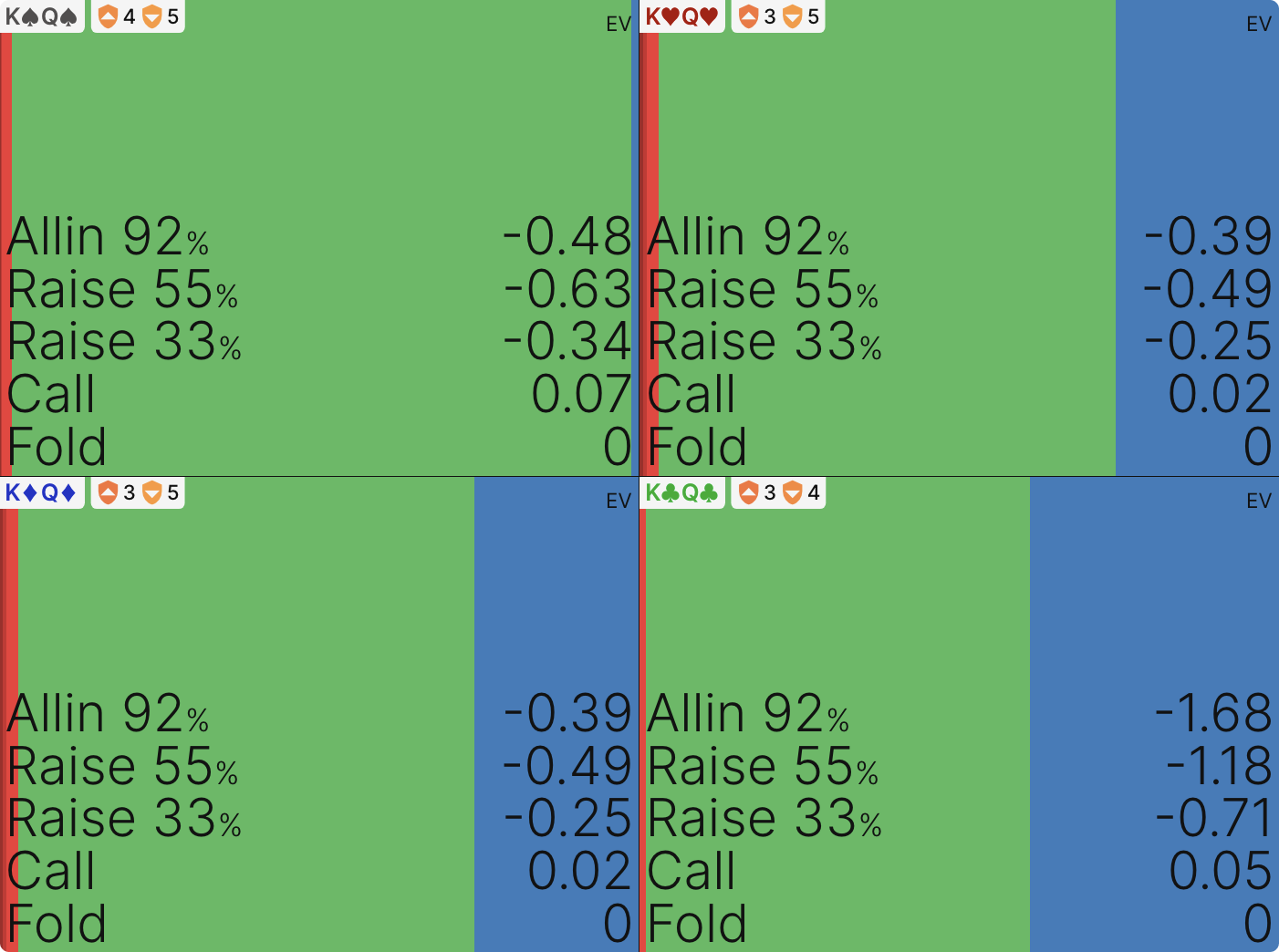

Assuming we make that 25% pot bet, this is the response from UTG:

Most cards continue because the bet size is small and this is the sort of board where neither player improves much, so preflop hand strength counts for a lot. One of the weakest hands that calls is KQs, which makes us as much as 0.07bb.

One of the few folds is KQo, which can lose us as much as 0.71bb.

If you see that KQs is a call, it would be easy to rationalize that KQo can’t be too bad as a call either, but the difference is significant. It can be as much as 0.77BBs, or 77 bb/100. On the surface it feels like the same hand, but the potential for a backdoor flush dramatically increases the value of KQs.

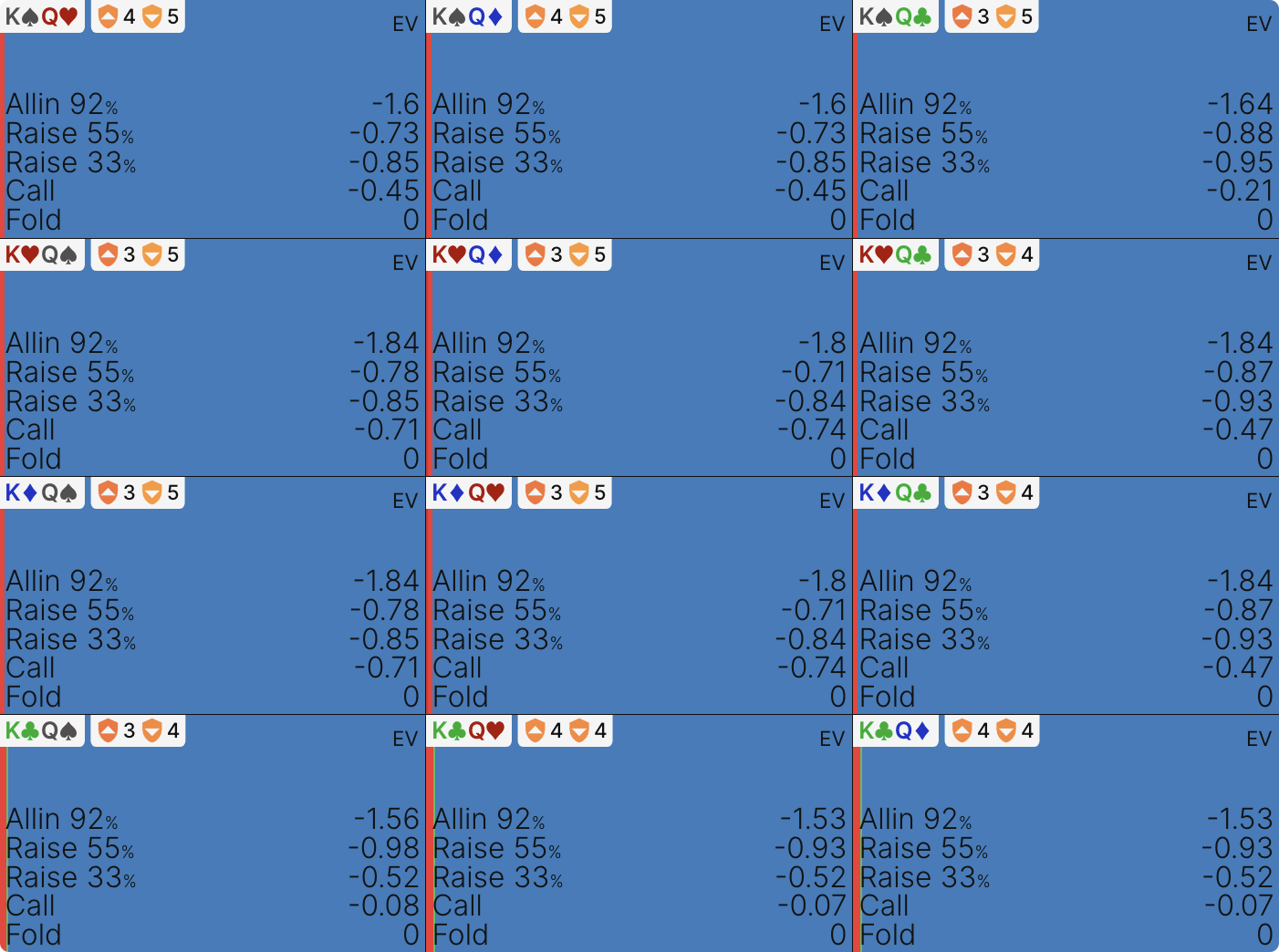

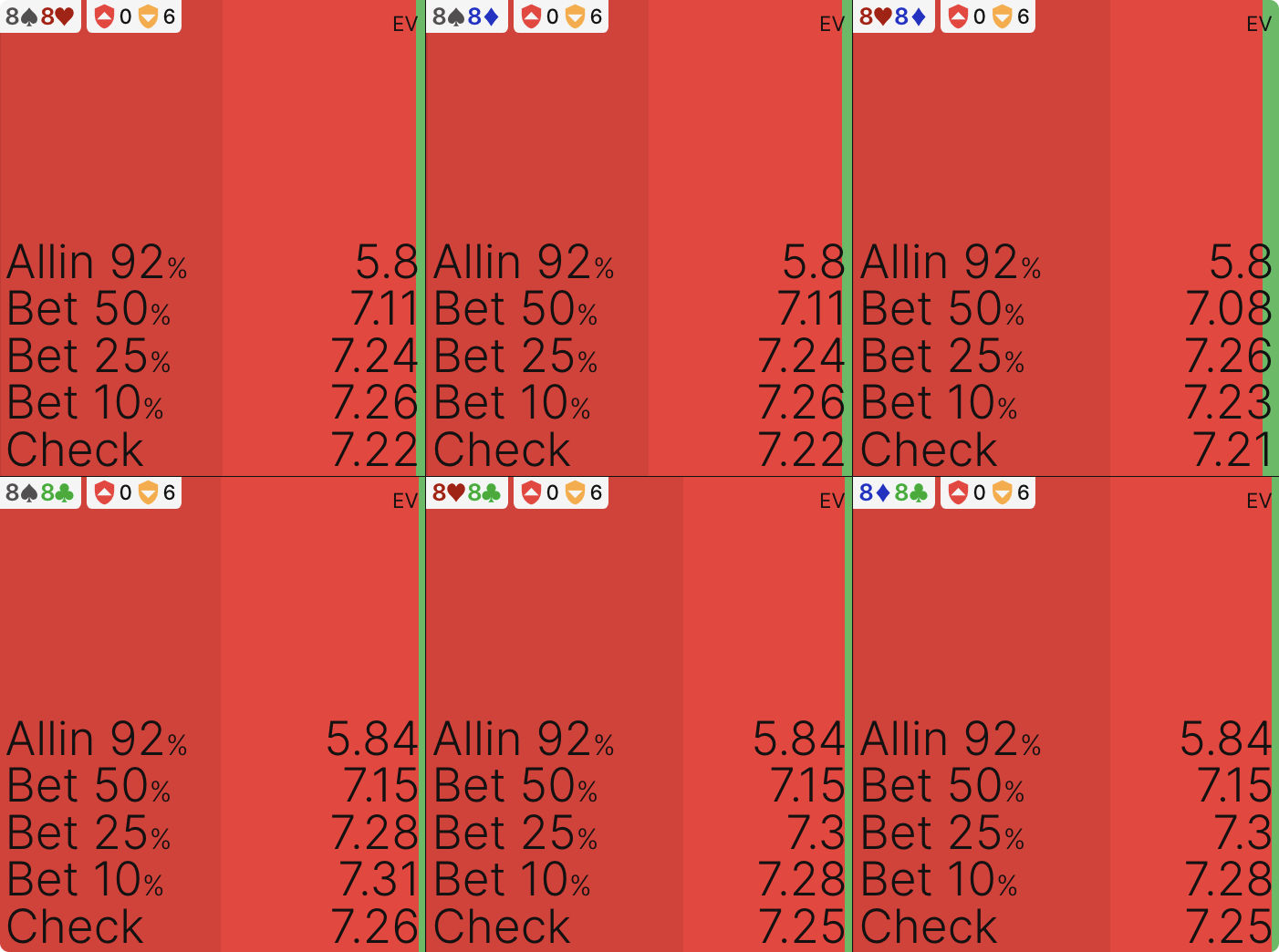

Let’s fast forward the hand, assuming UTG has called with the right range, and the turn is a K♠. This is what the SB does:

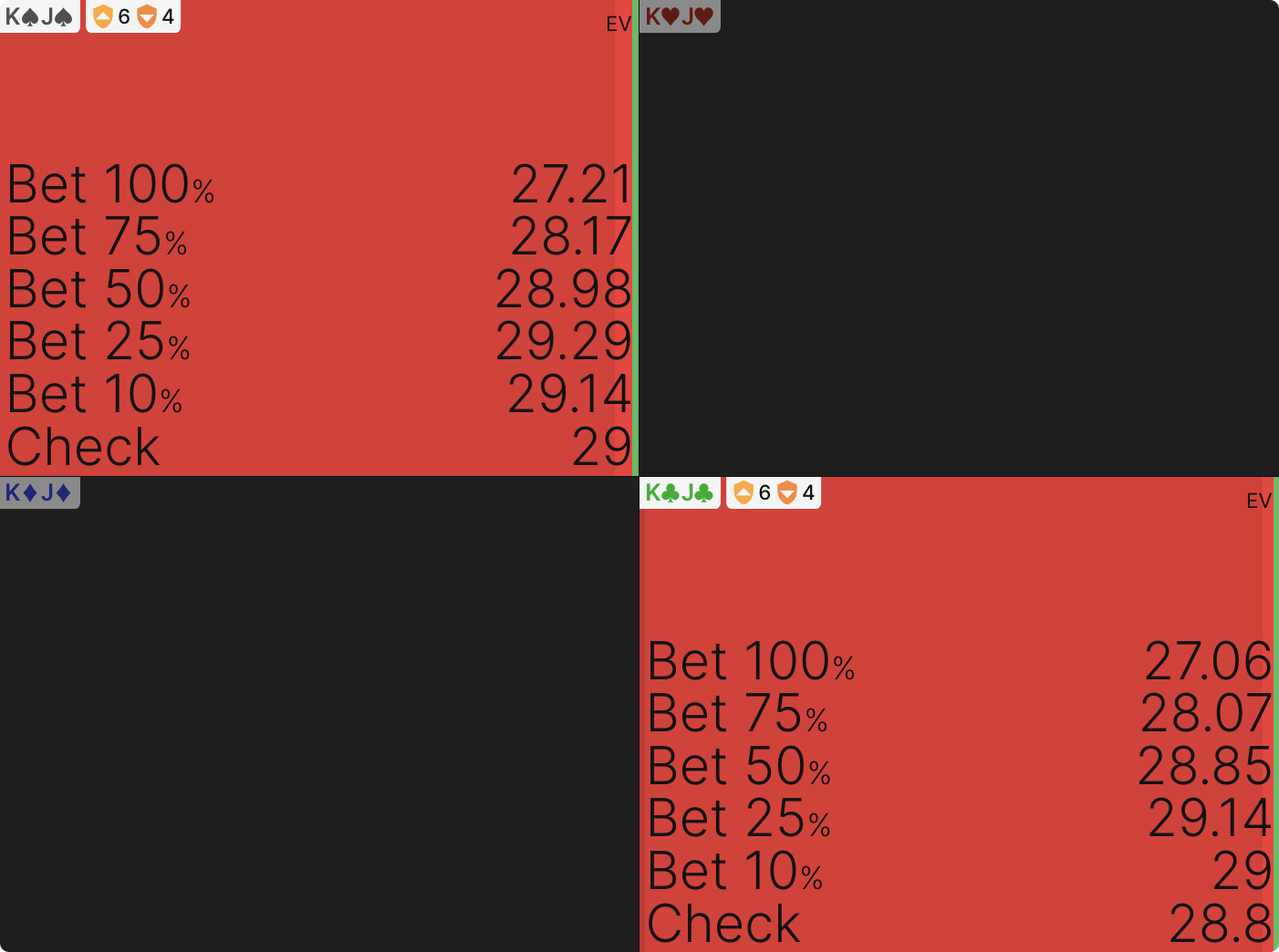

This is a good card for SB and they still have a significant range advantage, so the strategy is largely the same. 25% pot is still the preferred bet size. Let’s look at some random hands with varying strengths on this board.

Nothing has changed in terms of range advantage so once again, regardless of the hand itself, the preferred bet size is always 25% pot. Now the remaining KJs holding is very close to the nuts, but it still favors this smaller sizing. The difference between betting 50% pot and 25% pot is 0.87BBs, which is an 87 bb/100 error.

You will recall on the flop the difference between betting 50% and 25% was a 31 bb/100 error, now it is almost triple that. This is essentially the same strategic error, but almost three times as costly. This is for the rather obvious reason that the pot is bigger on the turn than it was on the flop, but it is still worth noting as a reminder.

The later you are in the hand, the more costly an error tends to be.

Endgame mistakes

Now let’s look at the cost of a mistake when ICM is a significant factor.

When you look at an ICM spot in GTO Wizard, EV is not measured in BBs but in tournament equity, as a percentage. The way this is captured is by taking the combined ICM value of the table (not the whole field), then expressing the EV as a percentage of that. So if, for example, the combined ICM value of the table is $1,000 and a hand has an EV of 1 in our sim, the hand would make us 1% of $1,000 on average, or $10 in real money.

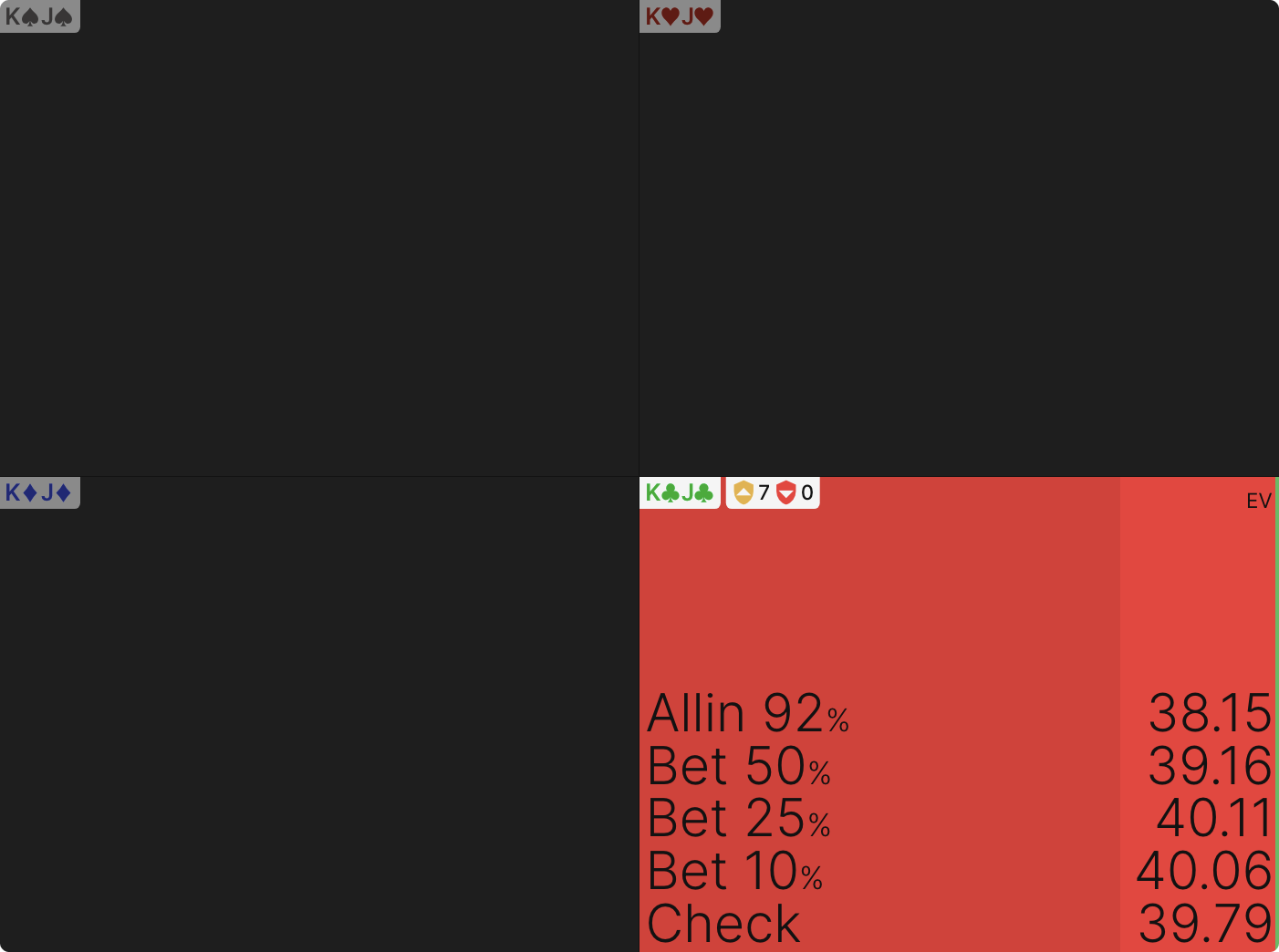

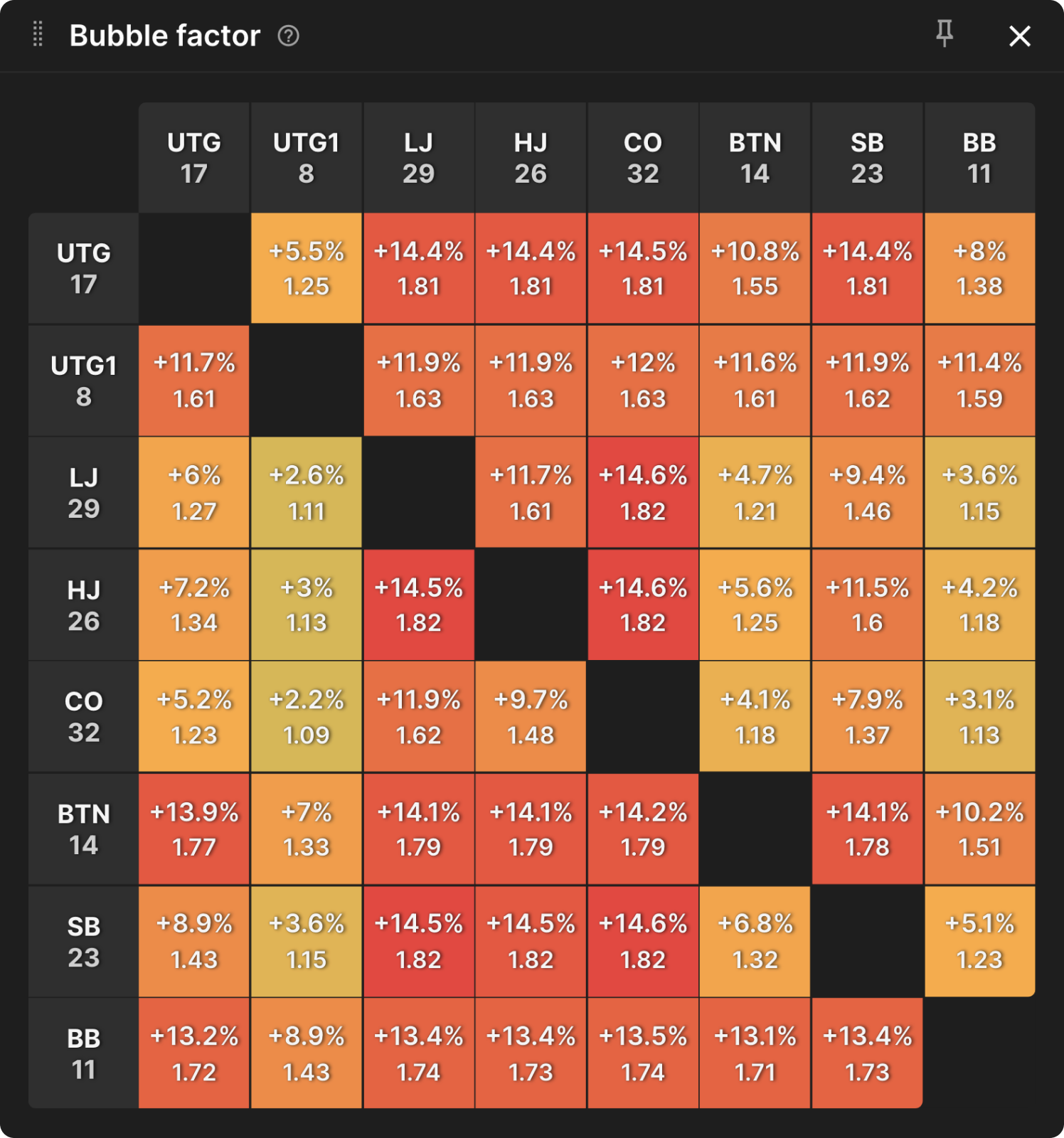

In this example, we are near the bubble and this is the table set-up and Bubble Factors.

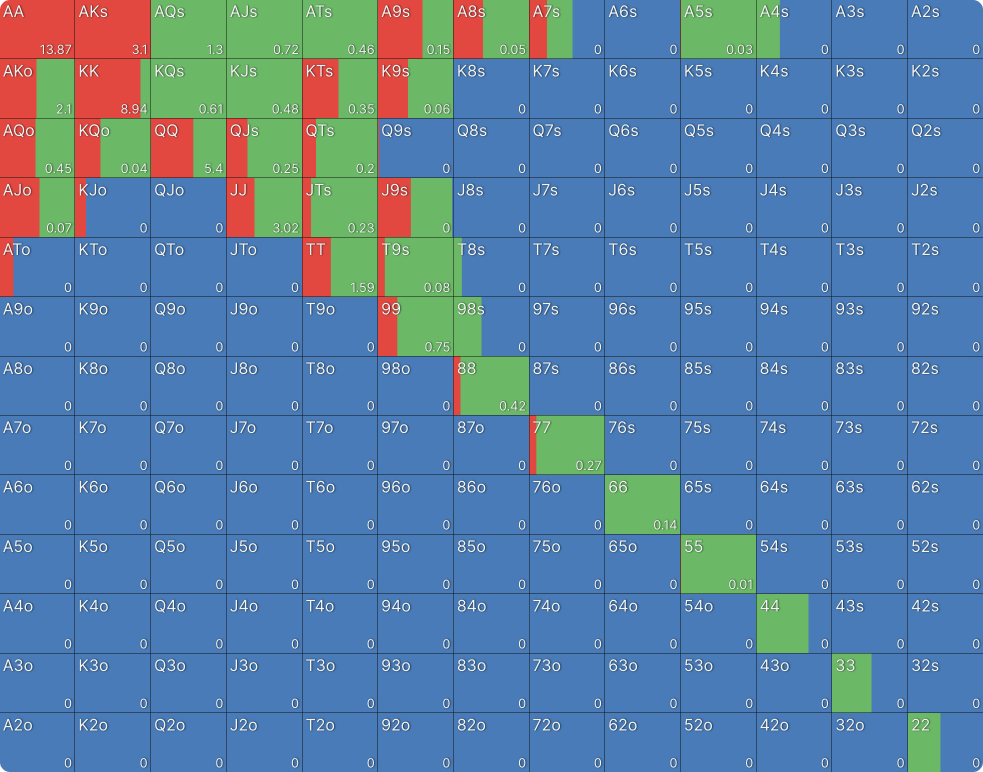

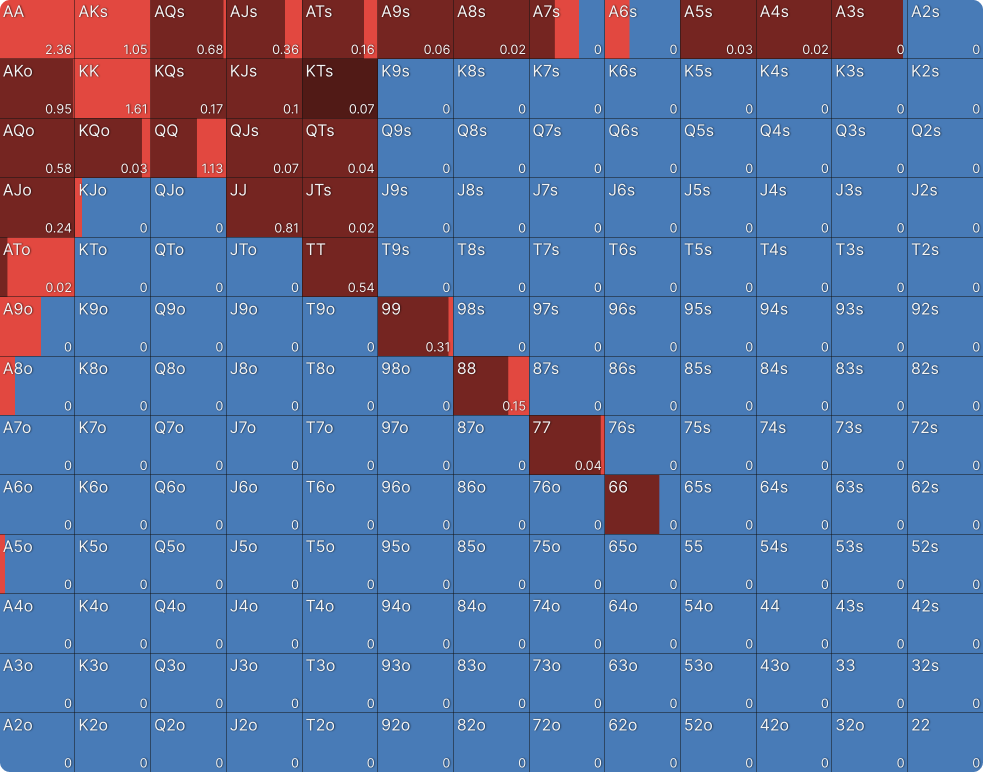

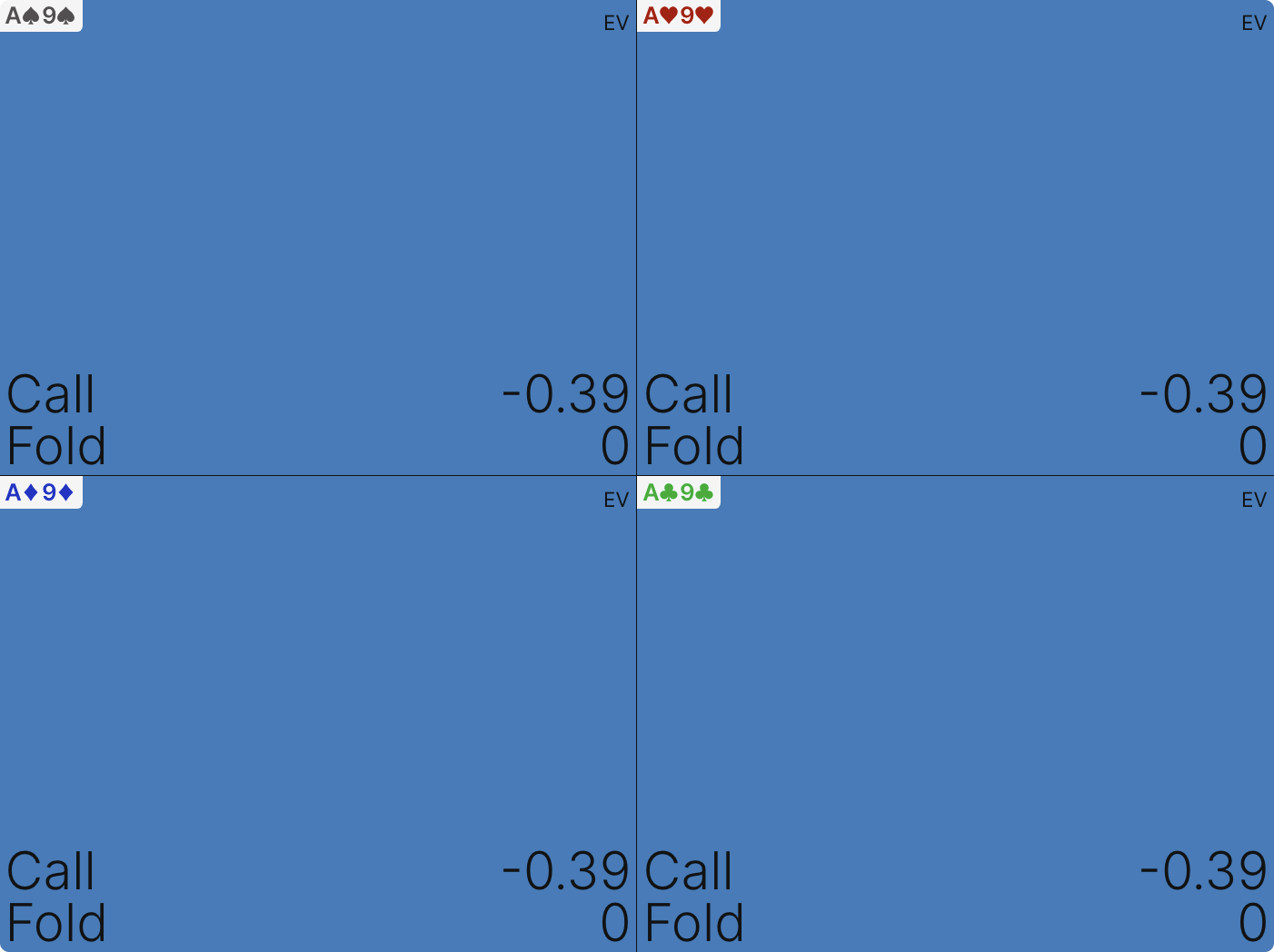

This is the range of UTG1, when it is folded to them:

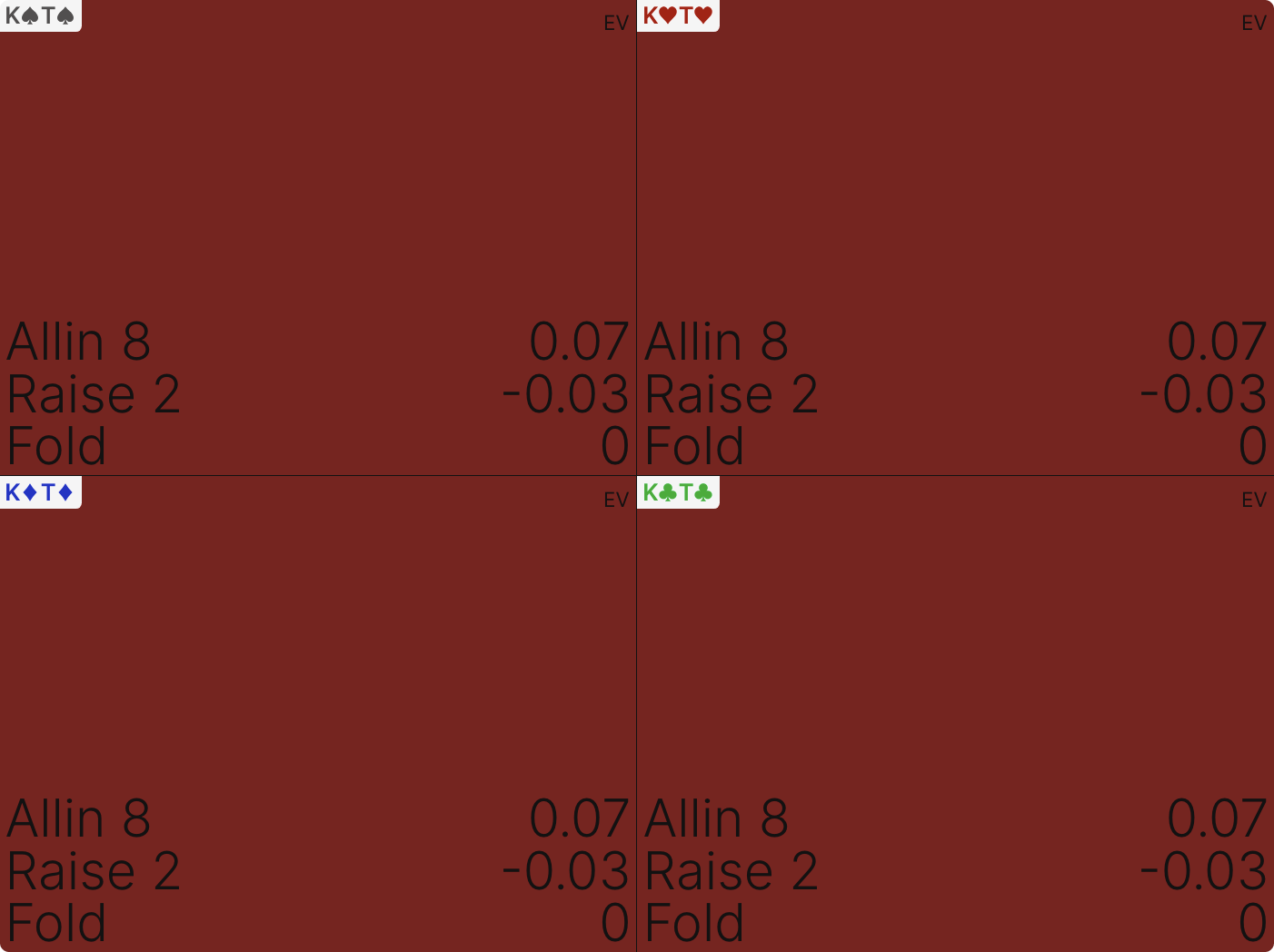

KTs is the last shove in the Kx grouping of hands and this is what it makes:

We saw earlier that there are some spots where shoving a hand is unprofitable but opening it is not. This is the inverse of that. Shoving is profitable here with KTs, it makes 0.07% of the table equity. Opening loses them 0.03%, the difference between the two is 0.1%. The reason for this is that shoving will work quite often, this particular hand blocks a lot of calls and it has decent equity when called.

It is unprofitable as an open because the range of hands that would raise over it dominate KTs and it would often be in a tough spot if it gets called, then misses the flop. This is a very important consideration when ICM is a factor, especially as a short stack. The last thing you want to do is enter the pot for a significant percentage of your stack and then be put in a tough decision for your tournament life, potentially having to fold. It is much better to use the leverage of your whole stack to put the tough decision on the other player.

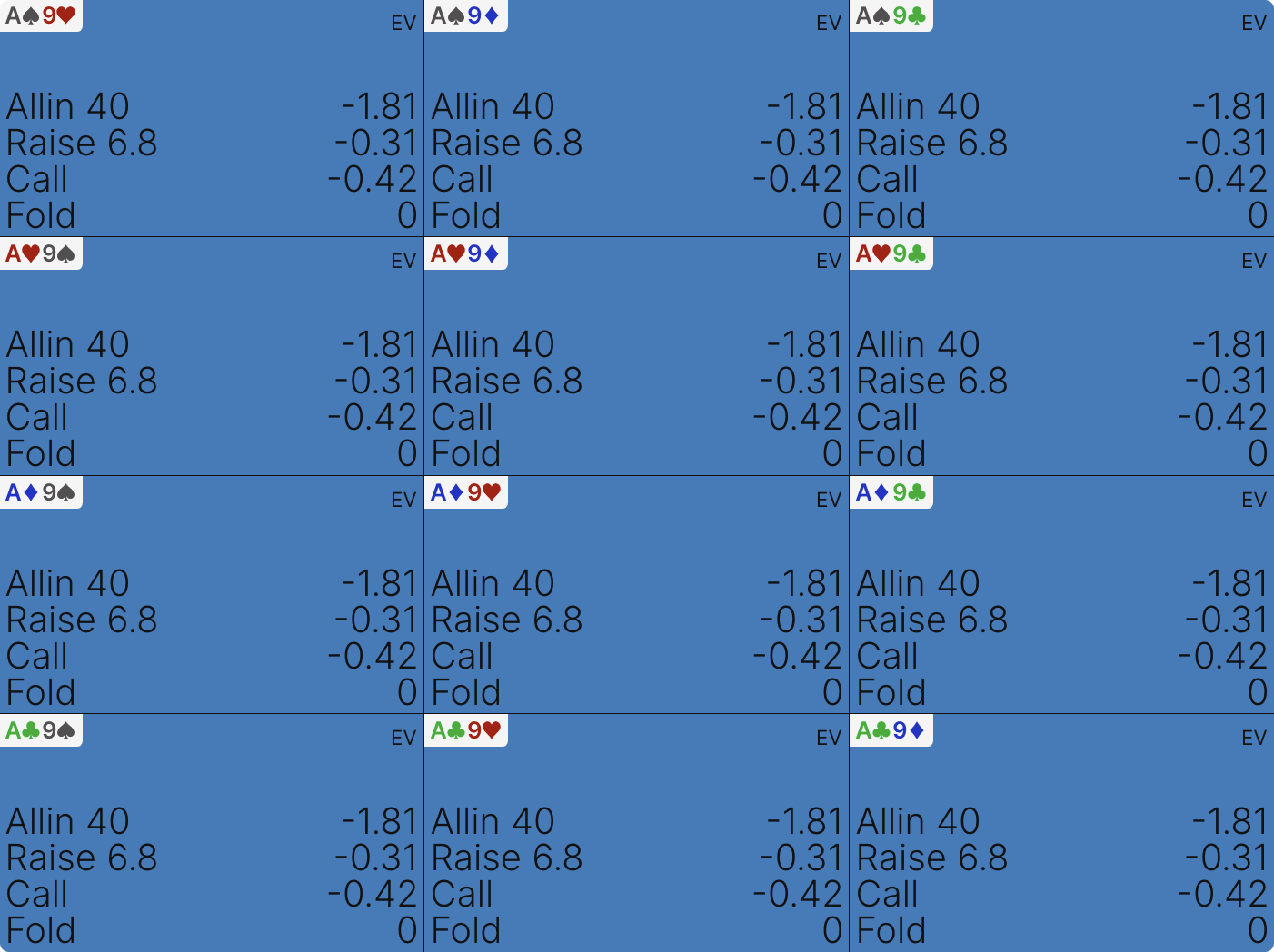

KTs is a profitable shove; this is what K9s would cost us:

K9s loses 0.03% as a shove, which is a 0.1% difference between that and KTs.

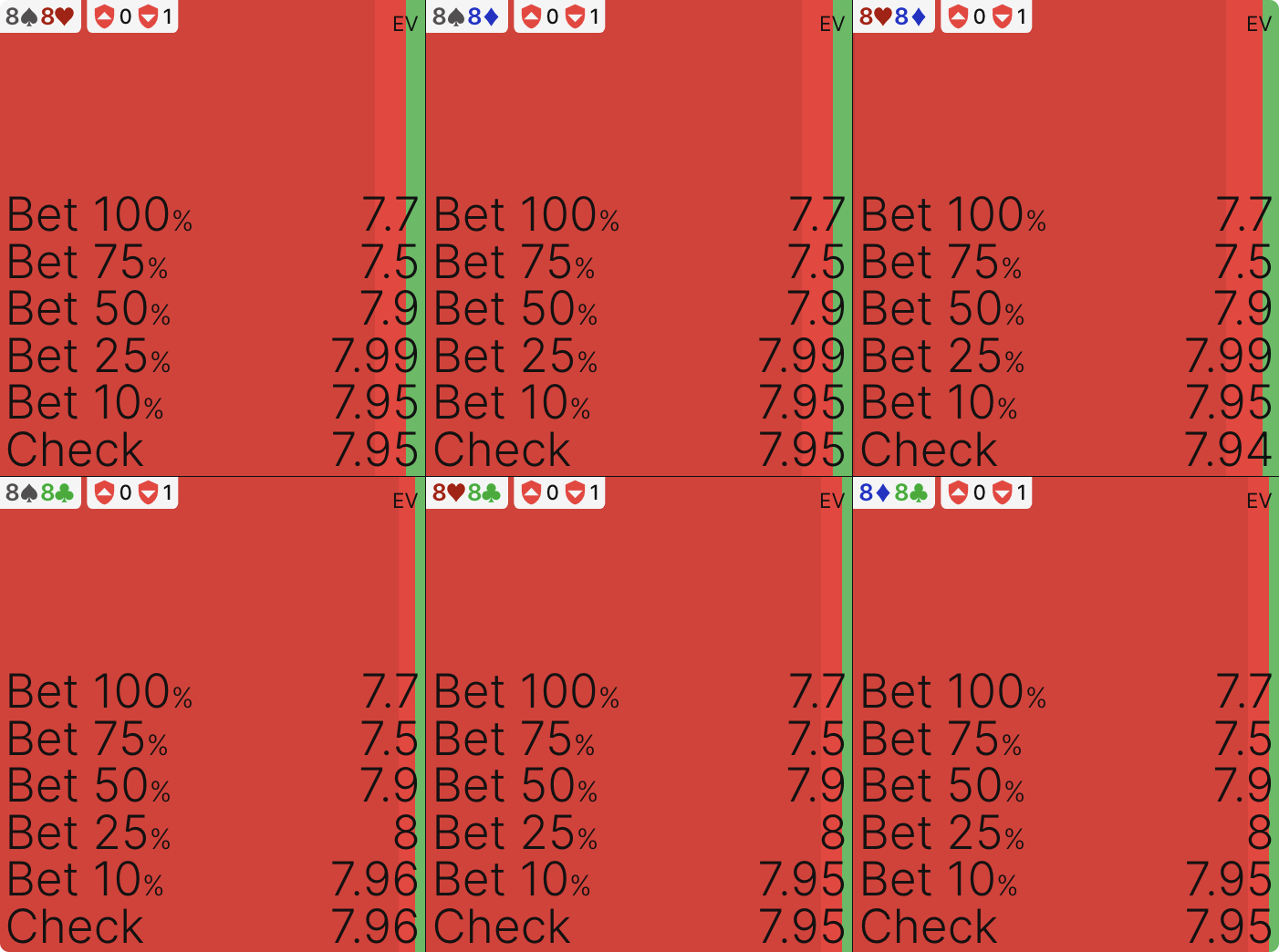

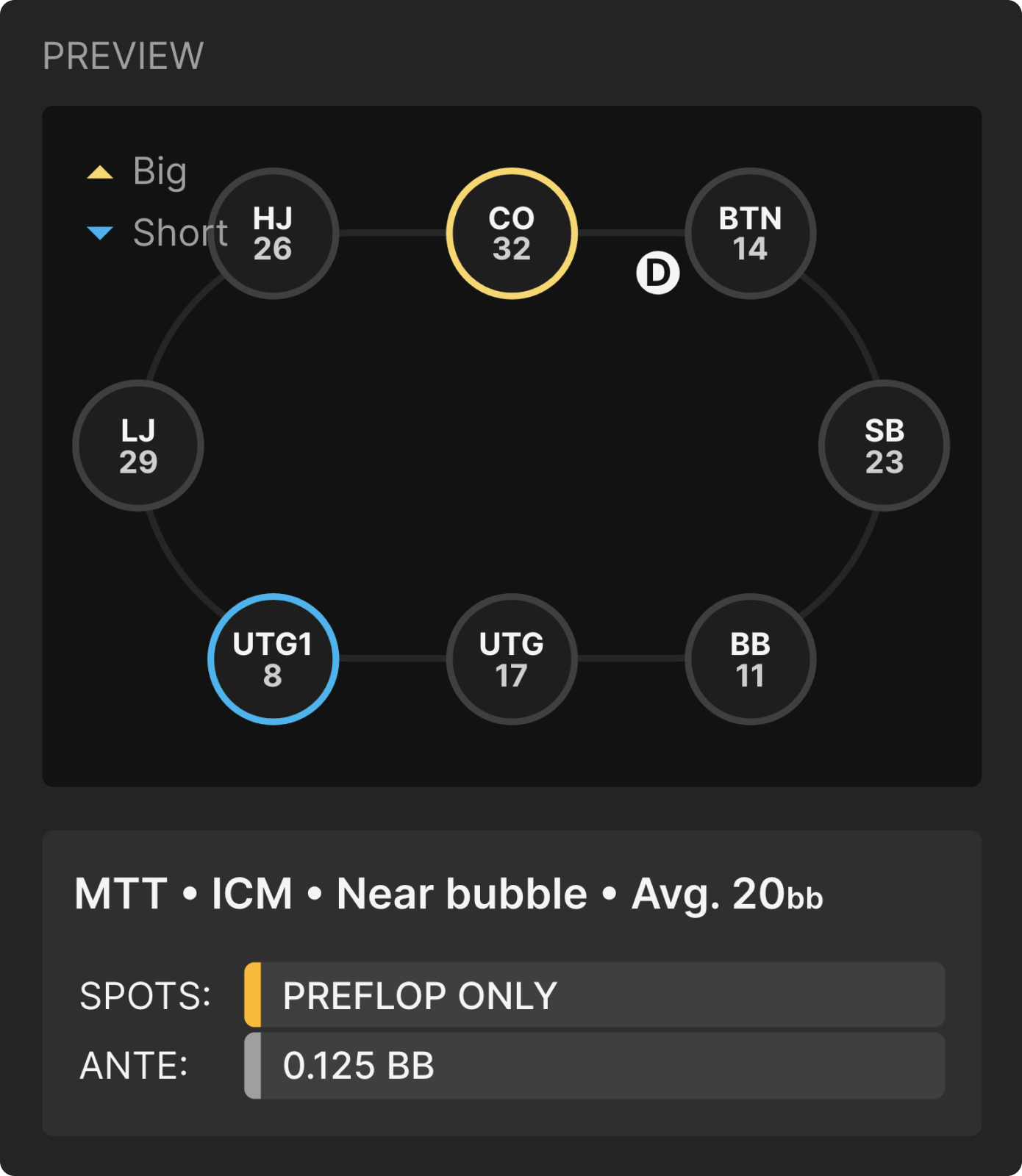

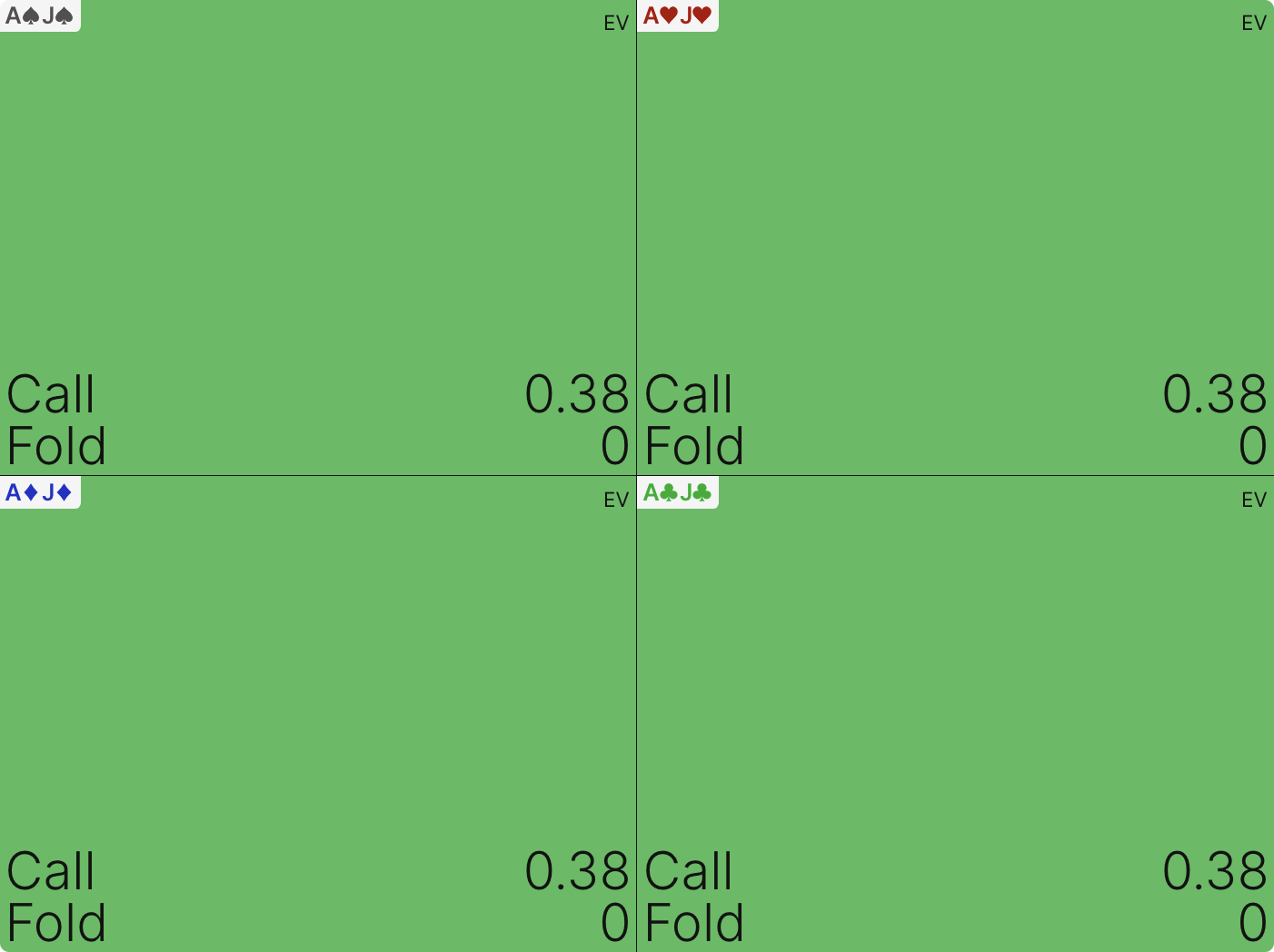

Assuming UTG1 shoves with the right range, this is the BB response. Remember, the BB is also short-stacked and losing would almost guarantee they bubble.

AJs is the bottom of our unpaired calling range and it makes us 0.38% of the table equity as a call.

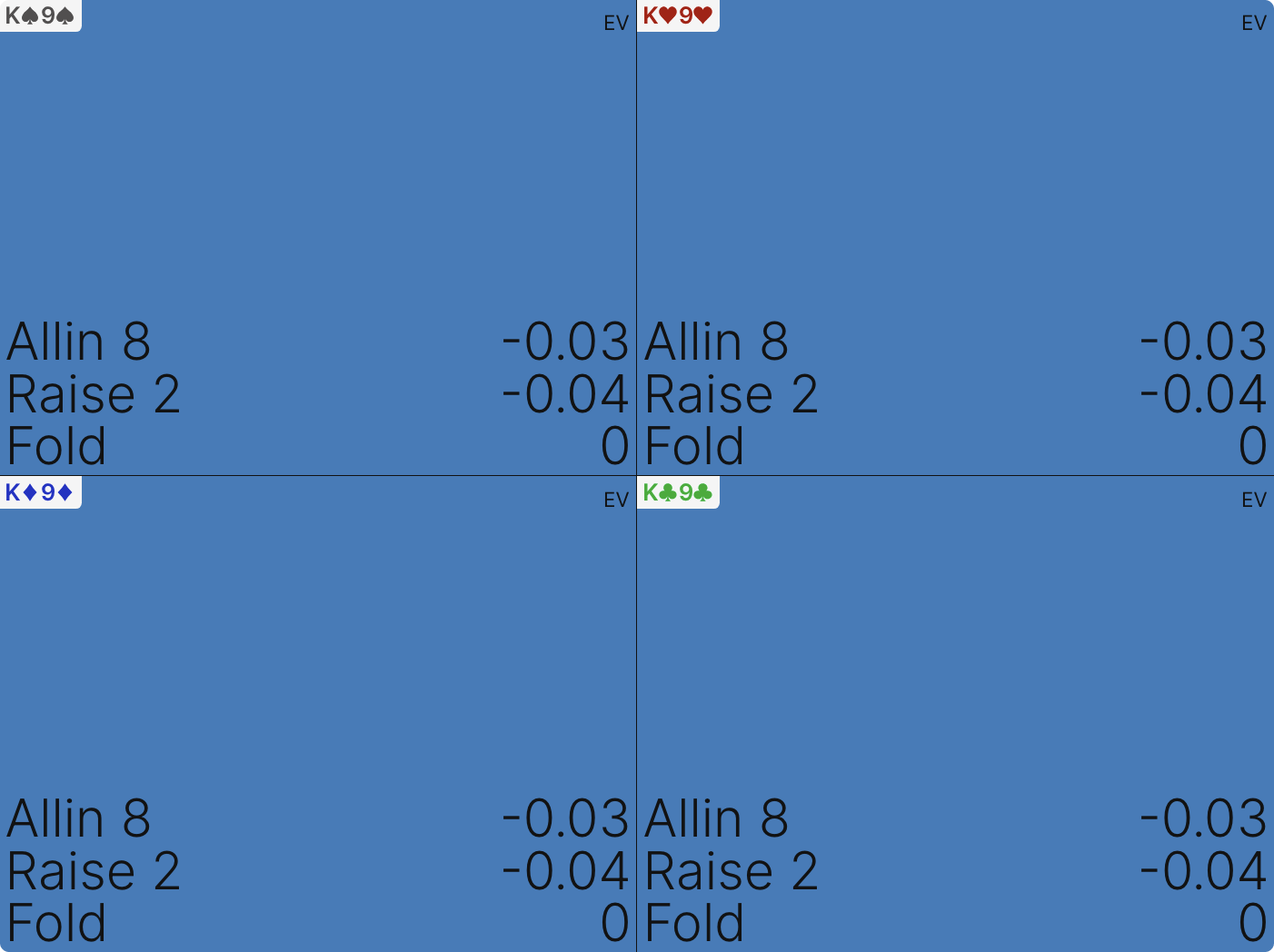

This is what ATs costs us:

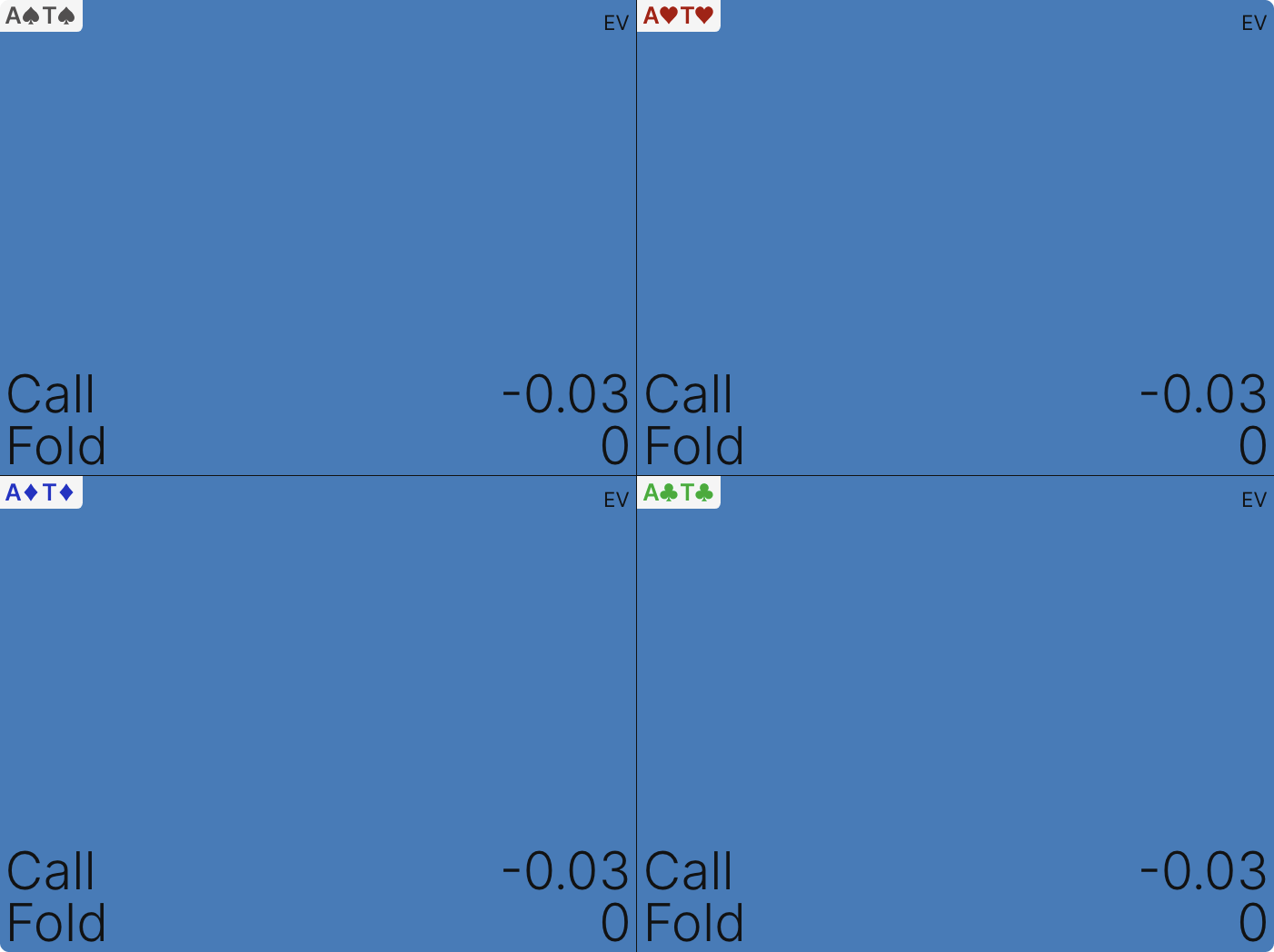

Now we are seeing quite a gulf between two close actions, the difference between a ‘good’ call and a ‘bad’ call is 0.41%. If we go two pips wrong, ie. if we call with A9s, this is what happens:

The difference is 0.77% between AJs and A9s.

There is a very important lesson here. In the previous example shoving incorrectly by one ‘pip’ costs us 0.1%, Calling incorrectly by one pip for the same amount of chips, as we did by calling with ATs, costs us 0.41%. The cost of a bad call is four times more than the cost of a bad shove.

This proves an old maxim of poker which went: ‘you need a stronger hand to call a raise than you do to make a raise’. A bad shove is not as costly because it still can have the desired effect of making your opponents fold. You can win two ways, by taking the pot down preflop or winning when called. It is a much smaller mistake because the average pot size will be much smaller because of all those folds.

A bad call is more costly than a bad bet because the pot is guaranteed to be larger and you need to have the best hand at showdown.

This is why studying ICM is crucial, the same table errors compound the deeper in the tournament you go. Rationalizing an error as ‘only’ losing x bb is not the way to think of these things, the real money cost of a mistake is far greater than that.

Going back to measuring things in terms of table equity rather than BBs. Let’s say you made a 3% mistake near the bubble of the $11 Sunday Storm, where the combined equities of the table were $200. That would be a $0.60 error and would not seem like much in terms of your $11 buy-in. Make the same mistake at the Sunday Storm final table where something closer to $50,000 in prizes are at the table, and that error has now cost you $150 in equity, which is an almost 14 buy-in error. A very small error, perhaps just one ‘pip’ outside of the correct range, has potentially cost a small fortune.

Poker Study Triage

Today, we have looked at what the difference is in EV between a hand that is at the bottom of a profitable range and the first unprofitable hand next to it in the grid. This shows us the cost of a mistake at the margins if you regularly make it.

- What this has also shown us is that some types of mistake are more costly than others.

- A bad fold technically costs us nothing, but it is an opportunity cost. It is an especially big opportunity cost if you have chips invested already.

- A betting mistake is not that much of an issue, because a bad bet can still get folds. Sometimes a bad shove is not as costly as a bad bet, because using the leverage of your entire stack leads to plenty of folds.

- A calling mistake is much, much, more costly. You cannot make people fold, you have to have the best hand at showdown, and the pots are much larger.

- A calling mistake when ICM is a factor is significantly more costly because the real money value of the error can compound. Get your calling ranges wrong at your biggest final table of the year, and it could cost you tens or hundreds of buy-ins in equity.

- Betting and calling mistakes also compound the further you are along in the hand. A bad call on the river costs you more because the pot is usually bigger than on previous streets.

When studying postflop, this also means that river mistakes are more important to fix than turn mistakes, and turn mistakes are more important to fix than flop mistakes. This is where the GTO Wizard Drill feature really pays for itself. Here you can quickly identify the types of mistakes you make and what they cost you, as well as specifically practicing the most costly spots without risking a penny of your bankroll.

This means there is an opportunity for low-hanging fruit where your poker study is concerned. Preflop it is more important to get your calling ranges drilled down before you start working on your opening/shoving ranges. This is especially true if you are studying ICM. Understanding your calling ranges is vital for final tables and bubbles. They could be some of your biggest money decisions of the year.

Key Takeaways

- If you are unsure what to work on, work on your biggest leaks.

- The difference between a profitable hand and a hand one ‘pip’ outside of the range can be significant.

- A betting mistake is not as costly as a calling mistake.

- Some hands are profitable bets but not calls, some hands are profitable shoves but not opens.

- The later the street, the more costly an error is.

- Errors compound the later you are in a tournament.

Author

Barry Carter

Barry Carter has been a poker writer for 16 years. He is the co-author of six poker books, including The Mental Game of Poker, Endgame Poker Strategy: The ICM Book, and GTO Poker Simplified.