What is Expected Value in Poker?

Expected value (EV) is the most fundamental metric in poker. Every decision you make is underpinned by one common goal – to maximize return. In order to do that, you need to weigh the long-term profitability of each and every action you take.

Expected value is how much you expect to win or lose with a specific play over the long run.

Where does EV come from?

Let’s imagine you played a game where everyone checked down every hand. Obviously, no one would have an edge because equity is evenly distributed. In order to gain you need to win more than your fair share.

So, where does EV come from? In its purest form expected value comes from organizing your equity more efficiently than your opponents. That means putting the right kind of hands into your betting/checking lines, knowing how to utilize sizing, knowing which hands are profitable enough to continue, and which hands to let go.

There are only two ways to win chips in poker; win the pot at showdown, or make everyone else fold. For this reason, most HUDs will organize your results graph into red/blue lines, indicating chips won with and without showdown. It then follows that there are two types of EV:

- Showdown EV – Chips won/lost at showdown

- Fold EV – Chips won/lost from folding or making your opponents fold

Fold EV, denying equity and folding out worse

One of the most fundamental aspects of fold EV is this: You cannot gain from folding hands that have no chance of winning against you. You gain from folding hands that could have beaten you.

If you have the nuts on the river, you can only gain EV by making worse hands put in money. This is the simplest example of gaining “Showdown EV”. You don’t gain anything from folding out worse hands (all you’re doing is shifting your “showdown EV” into “fold EV”). The only way to gain from folding your opponent’s 0% hands is if those hands could have bluffed you off your equity later.

Let’s say you bet top-two on the turn, and your opponent folds a flush draw. You gain EV from folding worse hands that can outdraw you, however, you also gain EV when worse hands call you. Denying equity from worse hands that can outdraw you can be thought of as a form of fold equity.

Typically you’d rather have worse hands call you. But if those worse hands have high implied odds against your hand it may actually be preferable to see them fold. This ties into the concept of over-realizing your equity.

Thin block-bet example

Let’s say you have 2nd pair, out of position, and block-bet the river. You’re gonna get called by better sometimes, you’re gonna get called by worse sometimes, you’re gonna get raised sometimes, and you’ll fold out hands that you had beat anyway. Did you gain anything from making worse hands fold?

The answer might be yes. Those worse hands that fold may have bluffed you off your pair had you checked. This block-bet may even have a negative showdown EV and still be the best play. This is why you’ll sometimes see solvers block-bet OOP with value hands that have less than 50% equity when called.

EV relativity

One of the most common misconceptions about expected value is that “folding is always 0 EV”. However, this is only true if you choose to define folding as 0. You could also measure EV as the difference in stacks relative to the start of a hand. This perspective is equally valid.

Imagine you 3bet to 11bb and face a 4bet of 25bb. If you fold, you’ve just lost 11bb. If you do that 100 times you’ll lose 1100bb! So how can this be if folding is always 0 EV?

From the perspective of your decision facing a 4bet, your original 11bb raise is a sunk cost, and folding can be considered 0EV. From the standpoint of your starting stack, folding lost 11bb. Both perspectives are valid. All you’re doing is comparing the EV of different strategic choices at the end of the day.

It’s important to realize that EV is always measured relative to something else. If you define folding as 0EV, then the EV of calling is relative to the EV of folding.

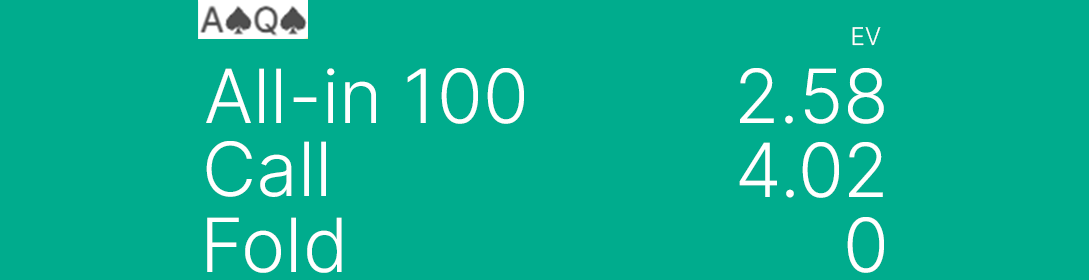

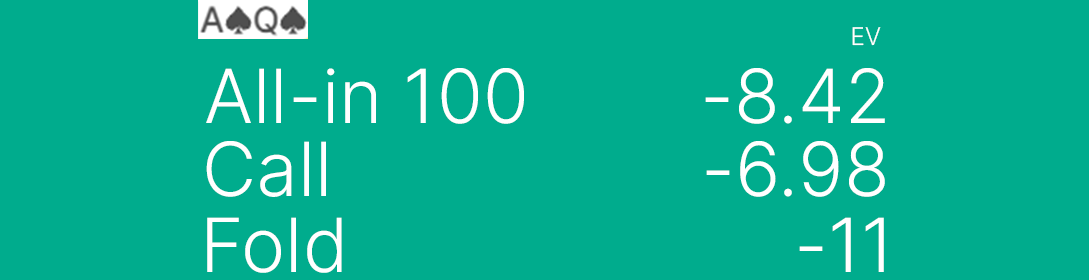

Here’s an example. You 3bet AQs on the BB and face a 25bb 4bet from the BTN. You have 3 choices: fold, call or shove. If you look at the EV of these options in GTO Wizard, you’ll see something like this:

As measured from your decision facing the 4bet: Folding is 0bb, calling is 4.02bb, and shoving is 2.58bb. These numbers above can be misleading. It makes it seem like calling and shoving are both “profitable”.

If you instead measure EV relative to your stack at the start of the round:

Folding is -11bb, calling is -6.98bb (4.02 better than folding), and shoving is -8.42bb (2.58 better than folding).

So regardless of how you look at it, calling is the best option, and it’s better than folding by exactly 4.02bb. But you need to realize that you’re deciding between 3 losing actions and trying to find the one that loses the least! It’s important to recognize this concept to put EV into context. These marginal “try and lose the least” spots constantly happen in poker.

EV Units of measurement

There are many different ways to measure EV. The most common way is to measure it in “bb” or “big blinds”. However, you can also measure EV in chips or pot share. For example, if you expect to win 3bb, and the pot is 5bb, you could say you have 60% EV (as measured by pot share, the same way we measure EQ). One result of this measurement is that you can have greater than 100% EV. This simply means you expect to win the pot and then some, in the long run.

Measuring your EV as a percentage has the benefit of putting things into perspective. For example, is 2bb a lot? Well, if the pot is 1000bb it’s extremely marginal, but if the pot is 5bb then it’s significant.

Tournament players must take an additional step and transform their EV into tournament value using something like ICM, DCM, or FGS. We’ll discuss the complications of transforming chip-EV into tournament-EV in later articles.

EV defined

The expected value is a weighted average that encompasses all future actions. The simplest definition looks like this:

EV = (Outcome1 probability x Outcome1 payoff) + (Outcome2 probability x Outcome2 payoff) + (Outcome3 probability x Outcome3 payoff)…

The box method:

- List all the possible outcomes. (Make the boxes)

- Find the probability and payoff of each outcome. (Fill the boxes)

- Put it all together in an equation and work it out. (Solve the boxes)

Calculation examples

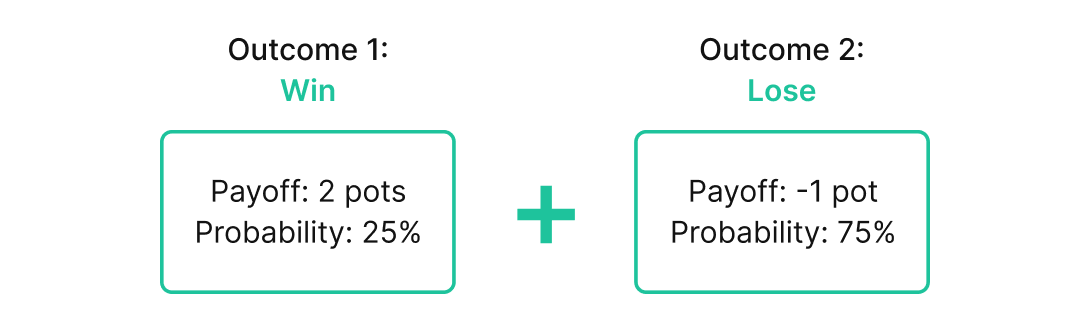

Example 1:

Let’s start with a simple example. Let’s say you’re facing a pot-sized shove with a 25% equity draw. If you call there are two possible outcomes, you win or you lose (excluding ties). If you win, you’ll gain the pot, and your opponents bet. If you lose, you’ll lose a pot-sized bet…

Win: 25% (+2 pot)

Lose: 75% (-1 pot)

EV = (25% x 2) + (75% x -1) = -0.25 pot

Clearly, this is not a good call as you’d lose 25% of the pot on average.

Example 2:

Now let’s imagine your opponent shoves half-pot, and you have 35% equity. You’re risking half a pot to win 1.5 pots (your opponent’s half-pot bet + the pot).

EV = (35% x 1.5) – (65% x 0.5) = +0.2 pot , winning 20% of the pot on average.

Example 3:

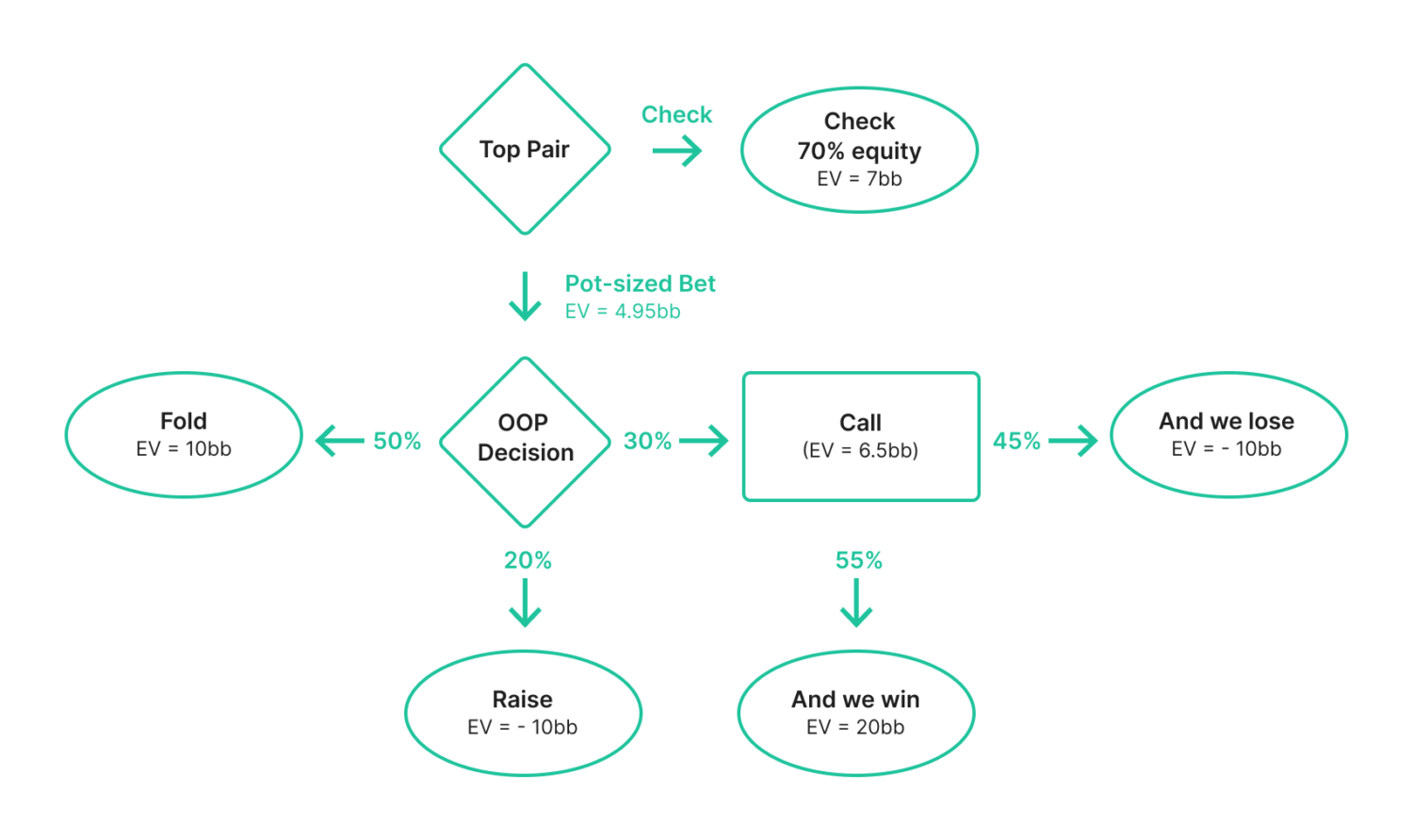

Let’s get a little more complex. We have the option to bet pot (10bb) on the river with top pair, but our opponent might shove and force us to fold.

- Equity when checking back: 70%

- Equity when we get called: 55%

- Opponent will shove (and we’ll fold) 20% of the time

- Opponent will fold 50% of the time

- Opponent will call 30% of the time

Is value betting too thin?

Payoff when we bet and get called = (55% * 20bb) + (45% * -10bb) = +6.5bb

Payoff when they fold = +10bb

Payoff when they raise = -10bb

EV bet = (fold% x 10bb) + (call% x 6.5bb) + (raise% x -10bb)

EV bet = (50% x 10bb) + (30% x 6.5bb) + (20% x -10bb) = +4.95bb

Hooray, the bet is +EV! That means we should bet right?! No. You need to weigh your options.

Checking back has 70% equity, which means we win 70% of the pot (7bb).

EV (bet) = +4.95bb

EV (check) +7.00bb

Betting loses 2.05bb of value since we’ll often get bluffed off our equity, fold worse and get called by better. Checking is clearly the best option here!

The full diagram looks like this:

Deriving other poker metrics from EV

Every poker metric you’ve ever heard of can be derived from an expected value equation!

Let’s start with pot odds. Pot odds refer to how much equity you need to call a bet. For example, let’s say OOP bets half-pot on the river. How much equity would IP need to make this call?

The classic way to solve this is to use the simple equation:

Required equity = (call) / (pot after you call)

For a halfpot bet: 0.5 / 2 = 25%; IP needs at least 25% equity to call this bet. Another way to say this is that IP needs to recoup at least as much money as they put into the pot.

However, this can also be calculated using the expected value. The benefit of this method is that it allows you to calculate more than just the break-even point. You can see exactly how much you’d gain or lose given some bet size and a certain amount of equity.

EV = (Win% x $Won) – (Lose% x $Lost)

- $Won = 1.5 (the pot plus villain’s half pot bet)

- $Lost = 0.5 (the amount to call)

- Win% = EQ

- Lose% = 1-EQ

EV = (EQ x 1.5) – ((1-EQ) x 0.5)

We can find the break-even point by setting EV to 0:

- 0 = (EQ x 1.5) – ((1 – EQ) x 0.5)

- 1.5 EQ = 0.5 (1 – EQ)

- 3 EQ = 1 – EQ

- 4EQ = 1

- EQ = ¼

- EQ = 25%

In other words, you need 25% equity to break even.

Alpha – refers to how often the villain needs to fold for you to break even with a 0% equity bluff. The classic equation looks like this:

risk/(risk+reward)

Where risk is the amount to bluff and reward is the pot you gain if they fold. For a half–pot bluff, the risk is 0.5 and the reward is 1.

0.5 / (0.5 + 1) = 33.3%

But what if they fold more or less? How profitable is the bluff then? Well, we can use an expected value equation to find out!

EV = (pot x fold%) – (bet x call%)

Now let’s derive alpha using EV:

Set EV to 0 in order to find the break-even point:

0 = (1 x fold%) – (0.5 x call%)

0 = fold% – (0.5 (1 – fold%))

fold% = (1 – fold%) / 2

2 fold% = 1 – fold%

3 fold% = 1

fold% = ⅓ = 33%

OOP MDF: Refers to the % of time OOP must call in order to prevent IP from having a profitable bluff with a 0% equity hand. We won’t go through the exact derivation as this is just equal to 1-alpha which we’ve already calculated above.

MDF = pot/(pot+call)

MDF = 1 / (1 + 0.5) = 66.6%

Or simply 1- alpha.

Conclusion

The art of valuing a hand is nuanced, complex, and can take a lifetime to master. Expected value is a key metric to every poker decision you’ll ever make.

Does this mean you need to be performing complex math in your head at the table? No, of course not, poker is more intuitive in practice. But you do need to understand how EV works in order to correctly think through your decisions, understand solvers, or do proper off-table analysis. Having worked through different scenarios off the table gives you a much better sense of what is and is not a good strategy.

Author

Tombos21

Tom is a long time poker theory enthusiast, GTO Wizard coach and YouTuber, and author of the Daily Dose of GTO.